Despite major legal and policy developments on behalf of crime victims since the landmark passage of the Victims of Crime Act in 1984 (VOCA), U.S. federal data collection efforts illustrate that significant gaps in access to and use of services persist for the majority of people touched by crime—including law enforcement–based victim assistance.

Data from the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS), the primary source for criminal justice statistics at the U.S. Department of Justice shed light on law enforcement’s current efforts in victim services, providing chiefs and other law enforcement (LE) executives the opportunity to ask themselves how their agencies measure up, as well as determine what more they can do.

The Importance of Law Enforcement–Based Victim Services

Since the passage of VOCA, more than 32,000 laws on behalf of victims have been enacted at the state, federal, and local levels across the United States, including the incremental addition of 35 state constitutional amendments, and robust statutory protections in all 50 states.1 Police officers serve an important role in the experiences of many victims, which sometimes is specifically reflected in these laws and policies. For example, there are now laws in 41 states mandating that police notify crime victims about the existence of victim compensation opportunities.

Recognition of the importance of these law enforcement–based victim responses is not new. In a concept paper originally published in 1992 and revised in 2010, accompanying the Model Policy on Response to Victims of Crime, the IACP Law Enforcement Policy Center stated that law enforcement is often a “gateway” for crime victims, going on to explain,

[victims’] perceptions of the system can be influenced by the manner in which they are treated at the first response and during the follow-up investigation. How law enforcement agencies treat victims is a direct reflection of an agencies’ philosophy of policing and core values. Organizations that place a high priority on addressing the needs of victims of crime are likely to build greater community confidence, increase crime reporting, leverage significant resources through expanded collaborations with community partners, and eventually reduce crime.2

Nearly four decades of growing commitments to victims, reflected in changes in victim-centered policies and programs, might suggest that most police agencies would report today that they are well equipped to meet the needs of victims. However, the latest available BJS statistics reveal a much different picture.

Victim Assistance Programs in LE: What We Know

BJS maintains more than a dozen national data collections covering federal, state, and local law enforcement agencies across the country that include data on special topics pertinent to the field. Most collections focus on aggregate or agency-level responses, providing critical information to police chiefs, policy makers, and others seeking to understand the picture of crime and policing in their jurisdictions and across the United States.

One of the most expansive of these collections is the Law Enforcement Management and Administrative Statistics program (LEMAS), which gathers responses from more than 3,000 state and local law enforcement agencies, including all those that employ 100 or more sworn officers, as well as a representative sample of smaller agencies in the United States.3 Conducted periodically since 1987, LEMAS obtains data on a range of topics including agency responsibilities, operating expenditures, officer demographics, community policing activities, training requirements, and more. The LEMAS survey also measures how law enforcement agencies are structured to provide victim assistance. These data tell an interesting story.

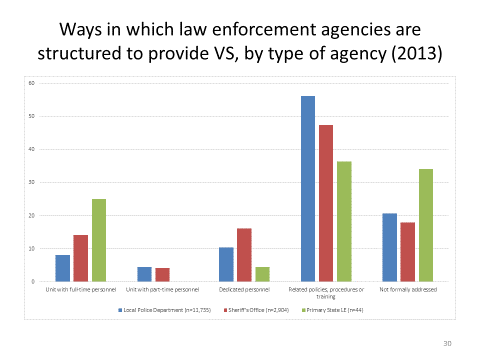

According to the most recent data available (LEMAS 2013), only 13 percent of U.S. law enforcement agencies reported having a specialized unit with full- or part-time personnel dedicated to victim assistance; and only an additional 12 percent reported having any dedicated victim assistance personnel. More than half of the agencies reported having no dedicated personnel but reported having some form of policies, procedures, or training related to victim assistance. The remaining 20 percent of agencies reported that the issue is not formally addressed.4

Figure 1: Ways in Which LE Agencies Are Structured to Provide Victim Assistance, by Type of Agency

Large agencies were more likely to report having a specialized victim assistance unit than smaller agencies. In 2013, nearly half of local police departments serving a population of 250,000 or more (49 percent) and nearly a third (32 percent) of sheriffs’ offices serving 250,000 or more operated a victim assistance unit with full-time personnel.5

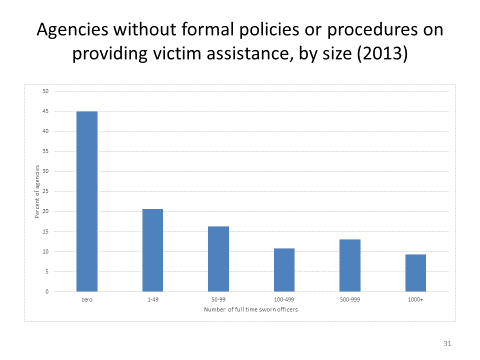

However, while the majority of agencies reporting no resources for victim assistance are smaller departments, there is also a significant number of large agencies in this category, including eight with 1,000 sworn personnel or more, many serving populations of 400,000 residents or greater.6

Figure 2: Agencies without Formal Policies of Procedures on Victim Assistance, by Size

Also important to note is the lack of increase in victim assistance units over time. Data from 2013 indicate that slightly more than one third (36 percent) of local law enforcement agencies employing 100 or more full-time sworn personnel operated a full-time victim assistance unit.7 This is only a 3 percent increase over 2003 (33 percent), notwithstanding a pivotal decade in the expansion and continued development of the victims’ rights and services movement nationwide.8

Agency-Based versus External Victim Service Partnerships

Law enforcement partnerships with allied agencies, like community-based victim service organizations, are a crucial component of the criminal justice response to victims. Law enforcement agencies that lack in-house victim service resources may seek to meet some of these needs through partnerships with community-based or other victim-serving organizations. Thirty-two percent of law enforcement agencies reported having a partnership or written agreement, such as a memorandum of understanding (MOU), in place with a local civic, business, or governmental organization.9 However, LEMAS data do not specify what type of partnerships these are and whether they include victim services, how the partnerships are structured, or how consistently they function.

Much more information is needed regarding the quality and specific characteristics of effective partnerships between law enforcement and community agencies, including how these arrangements work. For example, there can be a vast difference between an informal referral practice and an MOU-driven arrangement demonstrating a shared commitment to specific protocols and goals.

But are external victim service partnerships, even when effective, sufficient to meet victims’ needs? Part of the challenge faced by law enforcement agencies relying on external resources and personnel via partnerships alone is the potential to forgo the singular opportunity for supportive victim-police contact at the point of crisis and in the course of routine business. Without appropriate complementary training and resources, the existence of a partnership might, in fact, diminish officers’ sense of personal or agency-level responsibility for a victim-centered approach. This incongruity is potentially exacerbated by the many law enforcement responsibilities not directly related to victims, such as investigation, and how these duties might come into conflict with complexities of trauma and victim needs.

Even agencies that have led the way in the implementation of robust, trauma-informed programs do not necessarily have the same capacity available for victims across all victim characteristics and crime types. For example, agencies with a dedicated sexual assault or domestic violence program, a relatively more common law enforcement approach, might not be as responsive to the needs of victims of human trafficking, community violence including homicide, or other forms of assault. Agencies with victim assistance responses available between 9:00 a.m. and 5:00 p.m. might not be able to support victims who experience a crisis outside of those hours. Likewise, agencies that provide multidisciplinary crisis response may still have few civilian staff hours available compared to the extensive need for these services.

Victims’ Decisions to Report and Seek Services

In addition to LEMAS, other BJS data collections provide important information related to law enforcements’ response to victims. The National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS), one of the most comprehensive sources for crime and victimization information in the United States, measures the extent of nonfatal personal and household victimization and a number of related topics, including whether victims received access to the help they need. The NCVS, conducted annually by BJS since 1973, is set apart by its size and scope. Unlike the Uniform Crime Reports and other sources of statistical data from law enforcement agencies, the NCVS collects information directly from victims, making the data especially useful for providing insight into the nature of victim experiences and the characteristics of persons who access help and those who do not, regardless of whether the victim has reported the crime.

According to the NCVS, between 1993 and 2009, only 9 percent of serious violent crime victims reported accessing victim services. Serious violent crime includes rape or sexual assault, robbery, and aggravated assault.10 Between 2010 and 2015, nearly 10 percent reported that they had accessed victim services.11 These percentages are strikingly low, and, similar to LEMAS data, they raise important questions about why so many victims are not receiving assistance in the aftermath of crime.

The NCVS has long revealed both that a high percentage of victims do not receive services, and that a high percentage of victims choose not to report crimes to law enforcement. These data also demonstrate that victims who do not report their victimization are statistically less likely to access help. From 2010 to 2015, roughly 58 percent of serious violent victimizations were reported to the police (51 percent in 2016).12 Overall during this time period, 13 percent of serious violent crime victims reported receiving services when the crime was reported to the police, compared to only 5 percent when the crime was not reported.13 What became of the 87 percent of serious violent crime victims who reported the crimes to police, yet did not receive services? Clearly, opportunities for connecting victims with the help they need are being missed.

Victims who choose not to report their victimization cite a range of reasons, one being that they did not think police could do anything to help. The percentage of violent victimizations that were not reported for this reason doubled from 10 percent in 1994 to 20 percent in 2010.14 There are many factors potentially influencing this phenomenon, including the nature of the relationship and level of trust between victims and police in their community. This finding has implications for better understanding of victims’ perceptions about whether law enforcement agencies are both willing and equipped to meet their needs.

A recent study of NCVS data also concluded that reporting to police is associated with fewer future victimizations, underscoring the importance of reporting in preventing future crime.15 Receipt of victim-centered responses and services that further victim safety, healing, and stability may be playing a role in reducing future victimization, which is essential to law enforcement’s public safety goals.

Data Forthcoming

BJS recently fielded its next wave of LEMAS responses, the results of which will provide further insight into how agencies are organized and equipped to provide victim services. BJS, in partnership with OVC, is also currently engaged in a much broader effort to build this knowledge base through the NCVS Redesign and Subnational Program, and the Victim Services Statistical Research Program (VSSRP). (See sidebar.)

The VSSRP includes a number of groundbreaking efforts, starting with the first-ever National Census of Victim Service Providers (NCVSP), fielded in 2017, designed to enhance the understanding of all entities playing a critical role in serving victims, including law enforcement, community organizations, the justice system, campuses, hospitals, corrections, and legal aid organizations. The NCVSP will for the first time provide a quantitative snapshot of how many providers exist, as well as their organizational structures, types of services offered, crime types served, staffing considerations, funding sources, and more.

These developments are in addition to the continued transition of agencies across the United States to the National Incident-Based Reporting System (NIBRS).16 Together, these efforts will offer the most comprehensive picture of victim service provisions to date. Combining these new sources with other crime data will address key questions pertinent to law enforcement, such as how the geographic distribution of victim services in a state or city compares to crime distributions and other indications of need, and how law enforcement–based programs fit within the spectrum of crime prevention and victim response.

This new data infrastructure can also be used to demonstrate the value of investing in victim services, as well as to empirically demonstrate jurisdictions’ need for additional resources to improve their capacities. In 2014, the U.S. Congress quadrupled the amount of VOCA funding available through the Crime Victims Fund to support victim assistance, from $745 million to over $2 billion. This increase has been sustained, with $2.573 billion allocated in FY17.17

Notwithstanding the increased funding available to the field, the NCVSP pilot test revealed that 69 percent of participating law enforcement agencies said they were very or somewhat concerned about funding for victim services. Though not a U.S.-wide representative finding, it does support the widespread perception that the law enforcement community is neither fully aware of nor acting upon the potential presented by the increase in victim assistance funds, and/or facing challenges in their jurisdictions in accessing these resources. The data make a strong case for presenting to state VOCA administrators the importance of increasing the capacity of law enforcement agencies to provide meaningful services as part of a holistic victim-centered response.

The Future of Law Enforcement–Based Victim Services

The Office for Victims of Crime (OVC) is deeply committed to supporting the field in expanding capacity across a greater diversity of victim needs. OVC is funding groundbreaking initiatives lead by IACP and other critical partners, each with the potential to transform not only individual agencies and communities, but the trajectory of law enforcement–based victim services across the United States, including the following projects.

Enhancing Law Enforcement Response to Victims: Starting in 2003, OVC has partnered with IACP to create Enhancing Law Enforcement Response to Victims (ELERV), a strategy to improve law enforcement agencies’ response to victims of crime, with a focus on reaching and serving those victims who are often unseen and unserved. Already field tested at 11 pilot sites of varying sizes, the current ELERV project is growing this work into three new medium-sized jurisdictions (Casper, Wyoming; Chattanooga, Tennessee; and Saginaw, Mississippi), including a robust evaluation to add to the knowledge base of what works.

Law Enforcement and the Communities They Serve: Supporting Collective Healing in the Wake of Harm: This initiative, launched by the IACP in conjunction with the NAACP, and the Childhood Violent Trauma Center at the Yale School of Medicine, is designed to support five U.S. agencies in collaboration with their community partners (Baton Rouge, Louisiana; Houston, Texas; Minneapolis, Minnesota; Oakland, California; and Rapid City, South Dakota) in developing preventative and reparative victim-centered responses in the wake of officer-involved shootings or other high-profile events. Through the development; implementation; and assessment of comprehensive evidence-based and trauma-informed responses, protocols, and interventions, the initiative will also focus on officer health and well-being and promote problem-solving between law enforcement agencies and the communities they serve.

Integrity, Action, and Justice: Strengthening Law Enforcement Response to Domestic and Sexual Violence: Working with six U.S. law enforcement agencies (City of Shawnee, Oklahoma, Police Department; Clark County, Ohio, Sheriff’s Office; Denton, Texas, Police Department; Iowa City, Iowa, Police Department; Nampa, Idaho, Police Department; and Vancouver, Washington, Police Department), this demonstration initiative will build the capacity of law enforcement in identifying agencies’ strengths and challenges in responding to and investigating sexual assault, domestic violence, and stalking; raise awareness about the existence of implicit and explicit gender bias; strengthen community trust in law enforcement’s response to these crimes; and implement trauma-informed, victim-focused procedures across the United States.

Law Enforcement’s Role in Supporting Victims’ Access to Compensation: The primary goal of this project is to develop and deliver training, technical assistance, and resources to law enforcement to support crime victims’ access to compensation. It emphasizes an understanding of the current state of practice to identify gaps in the process attributable to law enforcement, such as ensuring that investigative reports are filed in a timely manner and include the information necessary to meet state eligibility requirements.

Implications and Outstanding Research Questions

The BJS data provide evidence for what many front-line service providers and victims have shared anecdotally for decades: there are significant gaps in law enforcement resources for and responses to victims. Often these gaps are most pronounced in the communities and populations most likely to be impacted by violent crime.18 Furthermore, NCVS findings do not account for the experiences of some of the most vulnerable victims that police interact with, such as those who are homeless, transient, in correctional facilities or otherwise institutionalized, and young children, who, by design, are not included in the NCVS household survey of persons 12 and older.

Building more consistent, trauma-informed, police-based victim services in the United States will require augmenting this statistical picture with more data about what works. Research-practitioner partnerships can assist local jurisdictions to understand their own unique context and challenges in a comprehensive assessment of victim-related needs and law enforcement’s capacity to meet them. Agency-level factors such as access to appropriate training, employee retention, data management, and information technology are critical in understanding how victims can most effectively be served. A collaborative approach to these assessments can assist law enforcement leaders in understanding what it will take for an agency to be victim-centered in its approach.

In addition to well-trained officers, victim response capacity may be enhanced by dedicated non-sworn staff working hand-in-hand with officers. Civilian staff can respond to the needs of victims in ways that sworn staff may be unable to, and the existence of such personnel may facilitate deeper aspects of an agency culture shift toward a victim-centered approach.

There are also important outstanding questions about how to maximize the effectiveness of law enforcement–based victim services, recognizing that, no matter what the agency’s capacity, some victims do not feel comfortable accessing services tied to the criminal justice system. Hospital and community-based programs have been game changers for many communities in more effectively serving and connecting victims with the help they need. Some of these community-based programs operate under thoughtful agreements with law enforcement agencies about how to meet victims’ needs and how to respect their privacy and autonomy to seek the help that is right for them.

The data suggest that, to reach more victims, the victim service infrastructure must include accessible pathways for all people harmed by crime and violence—pathways and venues including and extending beyond the justice system. Law enforcement leaders must participate in these conversations about how communities can best meet victims’ needs to support not only the healing of all victims, but the preventative, public safety benefits of enhancing law enforcement’s response to victims that is integral to their agencies’ success.

Law enforcement leaders committed to transforming victim services must participate in setting the research agenda on this topic, as well. The development of this knowledge base will continue to be critical to their ability to pursue meaningful, data-driven strategies in their communities and agencies.

Conclusion

While significant strides have been made on behalf of victims in recent years, the data reveal that there still is much work left to do to ensure that victims have access to appropriate services and support. At a critical moment in both policing and victim services, law enforcement executives hold great potential to be leaders at the intersection, simultaneously enhancing opportunities for victims to heal and recover while strengthening law enforcement effectiveness, public safety, and relationships in the communities they serve.

Notes:

1 International Association of Chiefs of Police (IACP), Model Policy for Response to Victims of Crime (Alexandria, VA: IACP Law Enforcement Policy Center, 2010); National Crime Victim Law Institute, “Victims’ Rights by State,” 2013.

2 IACP, Response to Victims of Crime, Concepts and Issues Paper (Alexandria, VA: IACP Law Enforcement Policy Center, 2010), 1.

3 U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ), Office of Justice Programs (OJP), Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS), “Data Collection: Law Enforcement Management and Administrative Statistics (LEMAS).”

4 DOJ, OJP, BJS, Law Enforcement Management and Administrative Statistics (LEMAS), 2013 (Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research, 2015).

5 Brian A. Reaves, Police Response to Domestic Violence, 2006–2015. (Washington, DC: DOJ, OJP, BJS, 2017).

6 DOJ, OJP, BJS, Law Enforcement Management and Administrative Statistics (LEMAS), 2013.

7 Reaves, Police Response to Domestic Violence, 2006–2015.

8 Reaves, Police Response to Domestic Violence, 2006-–2015.

9 Sixty-eight of local police agencies serving 250,000 or more, and sixty percent of agencies serving 50,000 or more report being in this category. Problem-solving partnership is defined in the LEMAS Glossary as “a collaborative partnership between the law enforcement agency and the individuals and organizations they serve to develop solutions to problems and increase trust in police.” Brian A. Reaves, Local Police Departments, 2013: Personnel, Policies, and Practices (Washington, DC: DOJ, OJP, BJS, 2015).

10 Lynn Langton, Use of Victim Service Agencies by Victims of Serious Violent Crime, 1993-2009 (Washington, DC: DOJ, OJP, BJS, 2011).

11 DOJ, OJP, BJS, National Crime Victimization Survey, Concatenated File, 1992–2015 (Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research, 2016.

12 DOJ, OJP, BJS, National Crime Victimization Survey, Concatenated File, 1992–2015; Grace Kena, Criminal Victimization, 2016 (Washington, DC: DOJ, OJP, BJS, 2017).

13 DOJ, OJP, BJS, National Crime Victimization Survey, Concatenated File, 1992–2015.

14 Lynn Langton et al., Victimizations Not Reported to the Police, 2006–2010 (Washington, DC: DOJ, OJP, 2012).

15 Shabbar L. Ranapurwala, Mark T. Berg, and Carri Casteel, “Reporting Crime Victimizations to the Police and the Incidence of Future Victimizations: A Longitudinal Study,” PLoS ONE 11, no. 7 (2006): e0160072.

16 E.g., a lower percentage of younger and male serious violent crime victims received assistance from a victim service agency, compared to older and female victims notwithstanding higher rates of serious violent victimization; and a lower percentage of victims with household incomes less than $25,000 per year in urban areas received assistance than in rural areas. Langton, Use of Victim Service Agencies by Victims of Serious Violent Crime, 1993–2009.

17 DOJ, Office for Victims of Crime (OVC), “Introduction: Implementing our Vision”; DOJ, “Office of Justice Programs (OJP).”

18 DOJ, PVC “National Incident-Based Reporting System: Using NIBRS Data to Understand Victimization,” 2014.

Please cite as:

Heather Warnken, “What Does the Data Tell Us About Law Enforcement–Based Victim Services,” Police Chief Online, April 4, 2018.