The beginning of the newly elected presidential government in Brazil in 2022 was marked by an attempt to break the democratic regime through the invasion and vandalism of the headquarters of the three branches of government in the country’s capital, similar to the event that occurred on January 6, 2021, in North America, when insurgents destroyed the protected area and looted the U.S. Capitol with the aim of preventing the certification of U.S. President Joe Biden’s election.

A week after the inauguration of the elected Brazil president, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, on January 8, 2023, a horde of supporters of the former president, who had been defeated in the presidential elections, dissatisfied with the election results, headed to Praça dos Três Poderes in the city of Brasília/Federal District (Distrito Federal, DF) and, within a few hours, vandalized public property, destroying internal areas of the Presidential Palace, the National Congress, and the Supreme Federal Court.

The facilities of the three branches were invaded by people opposing the results of the 2022 presidential elections, who, despite the lack of evidence of election fraud, contested the electronic ballot results. The followers of the outgoing president, the defeated candidate in those elections, were incited to oppose the election outcome, influenced by the mass dissemination of fake news on social media.

As a result, shortly after the election results were announced, supporters of the defeated candidate set up camps in front of armed forces units in various cities in Brazil and, in Brasília, in front of the Brazilian Army Headquarters. The number of demonstrators grew, marked by a protest on November 15, the date commemorating the Proclamation of the Republic, where they declared their refusal to accept the election results and called for military intervention to prevent the inauguration of the elected president.

From the insurgents’ perspective, the Brazilian Armed Forces could intervene in the electoral process if called upon by the president of the republic to guarantee law and order, a misguided interpretation of Article 142 of the Constitution of the Federative Republic of Brazil, as the Federal Supreme Court (Supremo Tribunal Federal, STF) and Superior Electoral Tribunal (Tribunal Superior Eleitoral, TSE) was perceived to have violated various provisions leading to the protestors’ undesired election result.

The first precedent for violent protests leading to the January 8 insurrection occurred in May 2020 with the establishment of the Acampamento dos 300, a protest against the Brazilian Supreme Court. This movement was dismantled by police intervention, with the camp leaders arrested and investigated in a separate inquiry established within the Federal Supreme Court, called the judicial inquiry into “anti-democratic protests” or the “fake news” inquiry, investigating radical actions against the democratic order incited by right-wing ideologues who, through social media, formed digital militias to deceive and mobilize citizens.

On December 12, 2022, after the president-elect had been confirmed, and without any response from the Brazilian Armed Forces or the president who, according to the protestors, should have called upon them, there was a violent protest in the streets of the federal capital, with buses and several other vehicles burned, and an attempt to invade the Brazilian Federal Police headquarters building to rescue a protestor who had been arrested by the Brazilian Federal Police that same day, identified as an inciter of criminal acts. Despite confrontations with the military police, no one was detained that day.

Two weeks later, on Christmas Eve, there was an attempt to detonate an explosive device in a tanker truck loaded with aviation kerosene near the Brasília airport. One individual was arrested that same day and two others later, with an investigation revealing that the attack was planned at the camp in front of the Brazilian Armed Forces headquarters in Brasília. All three were convicted of explosives and arson crimes, with one also convicted of illegal possession of a firearm and incendiary explosive device. The perpetrators intended to cause public disorder to induce the declaration of a state of siege and spark military intervention, aiming to prevent the inauguration of the democratically elected president.

Following these incidents, and after the presidential inauguration on January 1, 2023, there was a significant reduction in the number of camps across Brazil, including those around the Brazilian Armed Forces Headquarters in Brasília. However, even with a smaller number of people in the days leading up to the January 8 march, it is estimated that the total number of protestors at the Esplanada dos Ministérios on that day was between 4,000 and 5,000. Of those, 360 were arrested the same day inside the buildings they had invaded.

The insurgents left the camp in front of the Brazilian Armed Forces headquarters in Brasília on Sunday, January 8, 2023, with the majority arriving in the federal capital by bus. Internal surveillance footage from the Supreme Court shows the destruction of the ministers’ seats, the public area, and the courtroom where trials take place in a frenzy of public property destruction. In just over an hour, the insurgents, acting as true vandals, damaged or destroyed at least one item in the building every eight seconds, with 576 damaged or destroyed objects listed, including works of art, furniture, and IT equipment.

Relevant works of art in Brazilian culture and public buildings known for their historical, architectural, artistic, and documentary value were damaged. A panel by renowned Brazilian painter Emiliano Di Cavalcanti was torn in at least three places. The statue Bailarina by sculptor Victor Brecheret was dislodged from its base, and the Muro Escultórico by painter and sculptor Athos Bulcão was pierced at the base. The Balthazar Martinot clock, which belonged to the 19th century king of Portugal, Dom João VI, was knocked over and damaged by an insurgent who was later identified and arrested by the Brazilian Federal Police. The total public funds spent to cover the damages exceeded 20 million BRL (USD 4 million USD).

Police Response

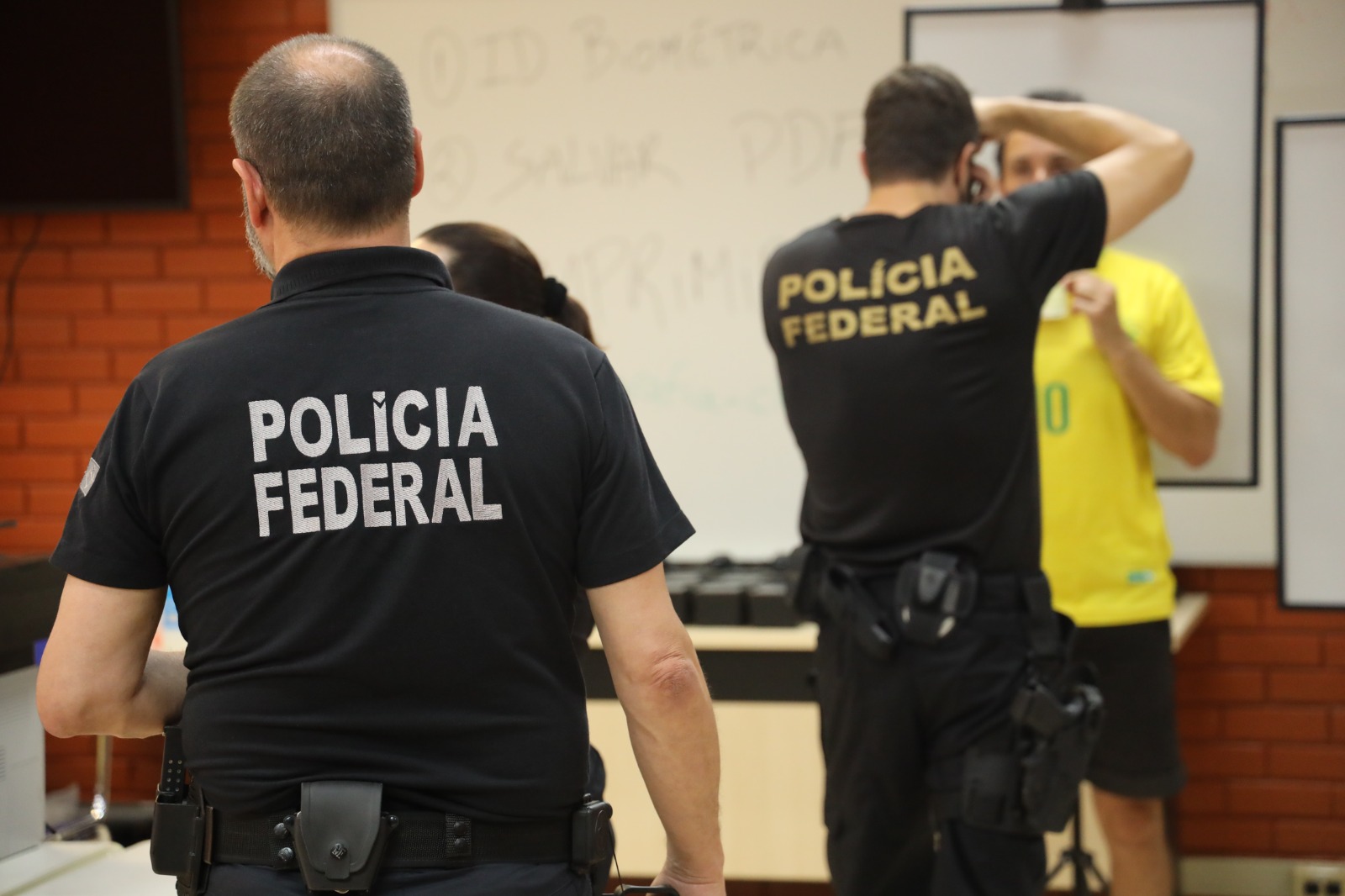

Security forces began clearing the buildings of rioters around 4:00 p.m. using nonlethal bombs and pepper spray. Helicopters from the military police and Brazilian Federal Police were also deployed, flying over the square and dropping gas bombs. The cavalry unit also took action, along with armored cars and other resources for controlling civil disturbances. Shortly before 6:00 p.m., the Presidential Palace and the STF buildings were completely cleared, with 360 people arrested red-handed inside the public buildings.

The following day, January 9, with the dismantling of the camp in front of the Brazilian Armed Forces headquarters in Brasília by order of the Brazilian Supreme Court, all those present were detained, totaling 1,929 people taken by the Brazilian Federal Police, with 1,154 remaining in custody and 775 released due to age or comorbidities, subject to precautionary measures such as nightly house arrest, weekly court appearances, and travel and social media bans, among others, and continue to face criminal charges for their actions. All those detained, arrested, and investigated were charged by the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office (MPF), and many have already been sentenced by the STF to around 17 years in prison, plus fines.

In general, those arrested and accused were charged with the crimes of violent abolition of the democratic rule of law, attempted coup d’état, aggravated damage to federal property, criminal association, incitement to crime, and destruction and deterioration or rendering useless of specially protected property (listed heritage). Furthermore, the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office signed non-prosecution agreements, already ratified by the STF, with 242 indicted insurgents who were at the Esplanada de Ministérios but did not invade the public buildings.

Investigation

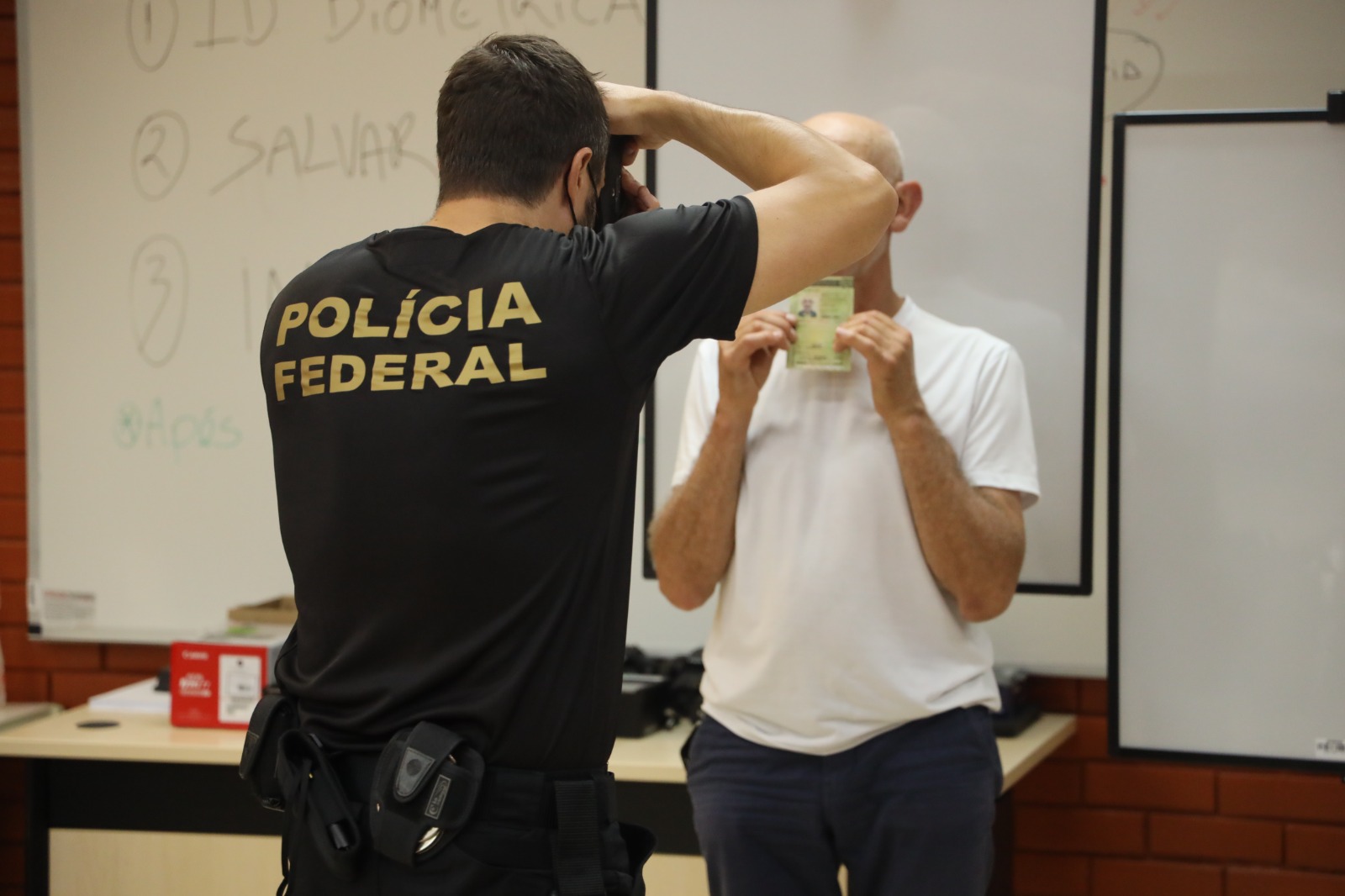

Following the violent demonstration, in addition to the mechanisms already in place, special reporting channels were opened so that those involved in the criminal acts could be identified by the public through the images broadcast by the media. Security footage and social media images were requested, and facial recognition techniques were used to identify and individualize the actions of the offenders.

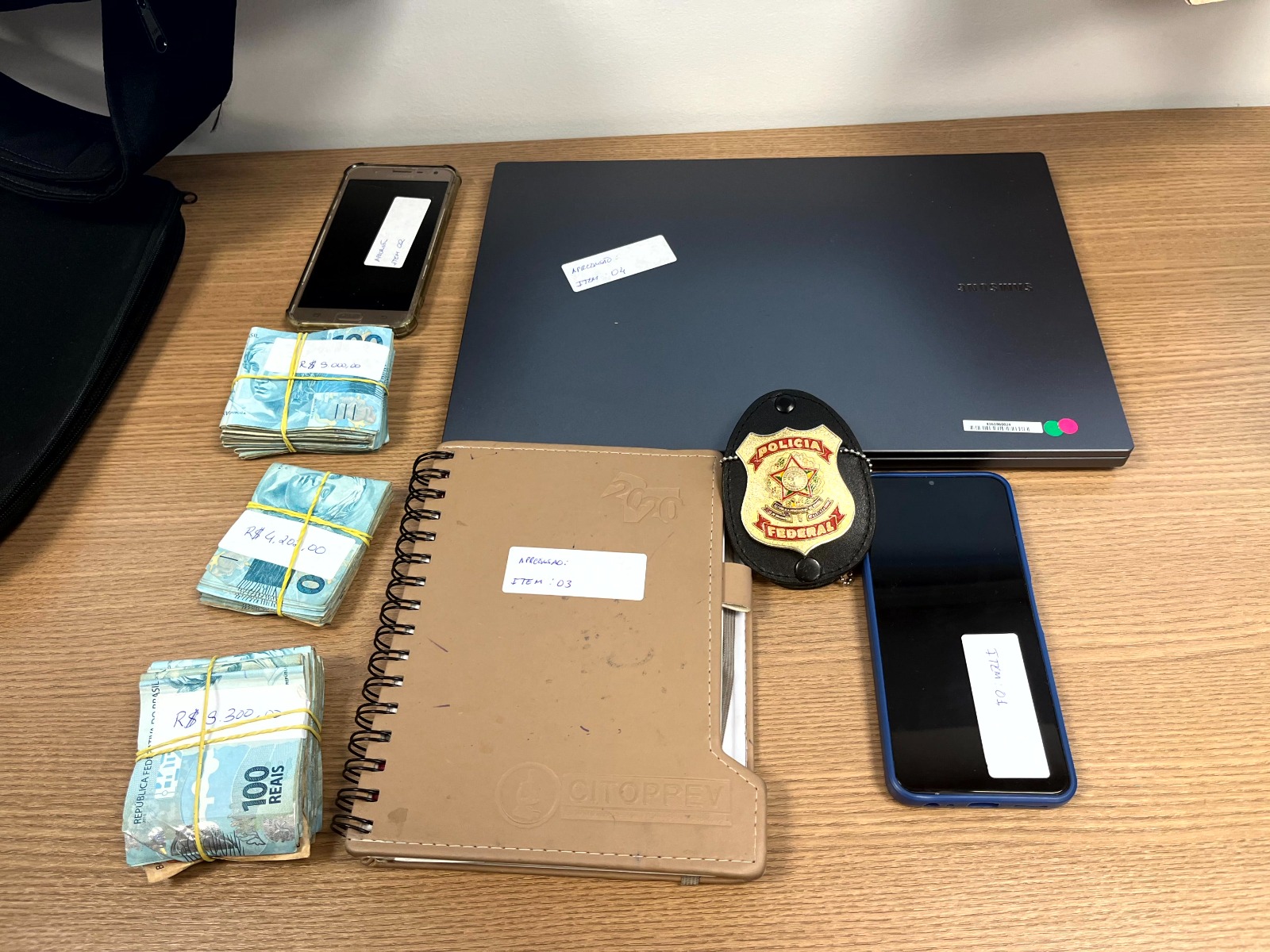

Consequently, hundreds of police inquiries were initiated, and several crackdown operations were launched, with search and seizure warrants, pre-trial detention, and the blocking of social media and financial assets. The Brazilian Federal Police’s overall judicial operation was called Lesa Pátria, executed in 29 phases over a year after the invasions. So far, Lesa Pátria has resulted in 180 preventive arrest warrants, 445 search and seizure warrants, and over 25 million Brazilian reais in seized assets. In order to better guide the investigative work, participation was classified, with classes ranging from those who took part in the march without committing vandalism, to vandals, inciters, organizers, financiers, and omissive authorities. The investigations are ongoing, aiming to identify more strategic actions in organizing and financing the acts.

These police inquiries are backed by substantial technical evidence. In addition to those caught in the act inside public buildings or in front of the Brazilian Armed Forces headquarters in Brasília the following day, many insurgents have been identified and tracked down by comparing surveillance footage with images available on social networks, the internet, and in databases accessed by the Brazilian Federal Police, using modern facial recognition techniques. Once the system has successfully compared the images, the police conduct further research to confirm that these suspects were in Brasília when the crime took place, notably using hotel guest lists, bus and plane passenger lists, vehicle registrations at toll stations, geolocation metadata from mobile phone apps, and data from cellphone base stations.

Once suspects have been identified, police teams go to the addresses to confirm identities through interviews, by checking residential and nearby street surveillance footage, and from accessing home entry logs, among other measures, all to confirm the suspects’ presence in Brasília on January 8, 2023, leaving no doubt about their participation. Many suspects facilitated evidence collection by posting about their presence and actions on social media, boasting about their criminal conduct.

In addition to facial recognition and the aforementioned measures, other techniques were used to identify and confirm the perpetrators of the investigated crimes. Fingerprints found at the scene and DNA traces were used for identification, placing suspects at the scene of the crime and providing undeniable proof of their involvement.

Once the perpetrators were identified, the Federal Police requested the Superior Court to issue arrest, search, and seizure warrants, as well as authorizations to breach bank and tax secrecy if necessary. The seizure of mobile phones and computers helped gather new evidence and identify other involved parties, including, notably, potential financiers. The disclosure of banking information helps confirm expenses incurred by suspects for maintenance, travel, and food, both for themselves and for third parties, leading to the identification of those who financed the insurrection, thereby aggravating their culpability.

It should be noted that the Brazilian Federal Police’s roles are defined by Brazil’s 1988 Federal Constitution. They do not handle physical security of installations and public roads, which is the responsibility of the military police in each state and the federal district, nor do they oversee the security of public buildings of the branches of the republic, which falls to the Presidential Guard and Institutional Security Office (GSI) for the Presidential Palace, the Legislative Police of the Chamber of Deputies and the Federal Senate for the National Congress, and the Judicial Police for the Supreme Federal Court.

However, the Brazilian Federal Police frequently exchange information with the state military police and plan public security actions together with other agencies. In the case of the January 8 anti-democratic acts, coordinated planning was conducted by the Federal District Public Security Secretariat. The Brazilian Federal Police participated in this planning and were part of the Integrated Public Security Intelligence Center.

Subsequent investigations revealed that high-ranking members of the Federal District Military Police took deliberate actions to avoid implementing the operational plan, which was crucial for the invasions and damage to occur. During the acts of vandalism in Brasília, images showed officers from the Federal District Military Police filming the destruction and talking to the insurgents in a clear show of support or acquiescence. The unlawful conduct of these commanders was confirmed by witness statements and text and audio messages extracted from mobile phones and computers, following the seizure of these devices by the Brazilian Federal Police.

In October 2023, the National Congress concluded a Joint Parliamentary Commission of Inquiry (CPMI). The approved report calls for the indictment of former president Jair Bolsonaro, as well as former ministers, members of the GSI, members of the Federal District Military Police, and a federal deputy who all contributed to the unlawful conduct.

The international community did not play a significant role in stabilizing the January 8 attempted uprising. National institutions, in full operation and synergy, demonstrated their capability to handle the events and subsequent criminal prosecutions. The Brazilian Federal Police developed internal processes to coordinate multiple investigations, utilizing business intelligence technologies, social media monitoring, human source identification, and facial recognition, among other methods.

Political Polarization

Reflecting a global trend, political polarization has been increasing in Brazil since 2017. Extensive campaigns by various conservative players and groups, with significant domination of social media by digital influencers, religious authorities, and liberal politicians, have aimed to discredit groups and adversaries across the political spectrum. The 2018 presidential elections were innovative in emphasizing themes never before central to political debate, such as abortion, drug policy, and gender issues, alongside traditional economic topics and candidate scandals. Since then, the political right has highlighted nationalist narratives, often associated with the term “patriot,” rejecting the “communism” represented by left-wing agendas.

Mainly due to the theme of nationalism, the political discourse seen among the insurgents attracts the support of extreme right-wing groups, which may have contributed to the radicalization observed in social media during the presidential elections. The engagement of these groups in Brazilian territory, initially small and mainly in the southern and southeastern regions, now presents a new challenge for public security agencies, advocating ultranationalism, fascism, Nazism, neo-Nazism, white supremacy, racism, racial segregation, anti-Semitism, and discrimination against non-heterosexual orientations, as well as separatism in southern states (Rio Grande do Sul, Santa Catarina, and Paraná).

As such, a portion of the more conservative population has been induced and radicalized, mainly through fake news or sensationalist presentations of true news as part of a strategy to recruit followers. Social media filter bubbles have formed, some of which radicalized and were responsible for the “herd effect” seen in the invasions of public buildings.

Finally, the Brazilian Federal Police’s ongoing investigation seeks to uncover the attempted coup aimed at preventing Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva’s inauguration, allegedly involving former president Bolsonaro, politicians, businesspeople, and high-ranking military officers, including the January 8 public building invasions. The Brazilian Federal Police repudiates any incidents by extremist groups and continues pertinent investigations under Operation Lesa Pátria.

A delegate for more than 20 years, Andrei Augusto Passos Rodrigues is the current director-general of the Brazil Federal Police. He was chief of security for Candidate Dilma Rousseff and Candidate Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva; liaison officer of the Federal Police in Madrid, Spain; and extraordinary secretary of security for major events, responsible for the security of the 2014 FIFA Soccer World Cup and Rio 2016 Olympic and Paralympic Games. A delegate for more than 20 years, Andrei Augusto Passos Rodrigues is the current director-general of the Brazil Federal Police. He was chief of security for Candidate Dilma Rousseff and Candidate Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva; liaison officer of the Federal Police in Madrid, Spain; and extraordinary secretary of security for major events, responsible for the security of the 2014 FIFA Soccer World Cup and Rio 2016 Olympic and Paralympic Games. |

Rodrigo Morais Fernandes is the director of intelligence of the Federal Police of Brazil. He has worked at the Federal Police as a federal police commissioner and investigator for 21 years. He also served as the director of intelligence for the major events in Brazil, coordinating intelligence activities during the 2014 FIFA Soccer World Cup and the 2016 World Olympic Games. Rodrigo also worked as a liaison officer at the Eldorado Task Force of the U.S. Homeland Security Investigations. Rodrigo Morais Fernandes is the director of intelligence of the Federal Police of Brazil. He has worked at the Federal Police as a federal police commissioner and investigator for 21 years. He also served as the director of intelligence for the major events in Brazil, coordinating intelligence activities during the 2014 FIFA Soccer World Cup and the 2016 World Olympic Games. Rodrigo also worked as a liaison officer at the Eldorado Task Force of the U.S. Homeland Security Investigations. |

Please cite as

Andrei Augusto Passos Rodrigues and Rodrigo Morais Fernandes, “A Nation in Turmoil: A Case of Insurrection in Brazil,” Police Chief Online, September 4, 2024.