Society has seen tragedy and crisis strike too many times over the last few years. Wildfires, hurricanes, tornados, and mass casualty events stemming from gun violence have seemed to plague the United States lately. These critical incidents seem to be the new norm, covered widely by the media with such aplomb and assurance that people have almost come to expect them.

There can be no greater task of leadership and accountability when tragedy such as a mass violence event or a mass loss of life event affects a community. The law enforcement agency that serves the public safety function for that community will be tasked with exhibiting strength, leadership, and accountability in maneuvering through the event and the aftermath.

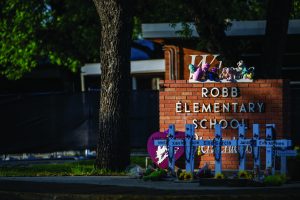

In the last 10 years or so, the public has become too familiar with locations and commonly named events like Sandy Hook; Parkland; Las Vegas; El Paso; Sutherland Springs; Uvalde; Washington, DC; San Bernardino; Pittsburgh; Virginia Beach; and Thousand Oaks. All of these U.S. communities experienced mass violence deaths exceeding 10 persons killed by a weapon in one incident. In many of the events, police were called upon to end the threat by force.

When events like this occur, the law enforcement leader will be front and center in the public eye, especially if the event is well covered by the media. Urban or rural, small or large, tribal land or county land, or in a city or a town, the primary responding law enforcement agency, along with secondary and tertiary responders, will be placed in the spotlight immediately and thereafter with potential reviews and investigations based upon responses and causes.

The expectation is that these unnatural events will occur, and many leaders will be thrust into the public eye, proving their worth as they navigate their way through these events and the aftermath. The essence of accountability requires that leadership responds effectively to the horrific event that has befallen their community.

Accountability also requires leadership to handle and, when possible, communicate the known details of the events with clarity and sensitivity.

Navigating significant events like a mass violence shooting will continue to challenge the entire community, first responders, and health services. For those who lead law enforcement agencies, a mass casualty incident can be and probably will be the most challenging event they will face in their law enforcement career.

Tragedy, Emergency Response, and Trauma

Tragedies and crises are by their very nature unanticipated dangerous situations. Law enforcement are typically the government representatives asked to decisively react with immediate resources to mitigate the loss of life or injuries to persons. The failure to be prepared or to react adequately to any potentially traumatic event can impose immeasurable reputational damage to the government charged with safekeeping a community.

Communities have become better at planning for many of the traumatic disasters and events that may occur. As for police officers today, they receive an enormous amount of training to successfully respond to a wide range of complex circumstances.

That training and education is ultimately necessary if the police are to be truly effective in limiting the loss of life during incidents of violence. Police officers, through training, are often required to effectively and tactically respond to a mass violence event and courageously put down the threat to others. In a great majority of the time, police officers successfully bring powerfully complex and dynamic events to successful conclusions where loss of life is minimized.

Trauma from these events can set off a series of mental health issues that, if left unresolved, can become long-term mental health conditions. In addition, the daily grinds of policing have been identified as the cause for often-undetected stress-related illnesses and diseases in officers. Therefore, it is imperative that the vast amount of training and education that police receive include health-related skill sets and wellness strategies to effectively deal with any potential mental health and stress-related fallout from the experiences of policework.

Adding to the stress of daily police work today is the fact that law enforcement has encountered significant mistrust from within the community and the media regarding police interactions with the public, particularly interactions with marginalized groups. That scrutiny has set in motion efforts to improve community-police relations through updating cultural protocols and policies.

However, occasionally, no matter how well-trained and prepared emergency responders are, they may not be able to prevent a loss of life. Recent unimaginable community tragedies like Sandy Hook, Parkland, and Uvalde can and will challenge the most veteran, experienced, and well-trained officer, both during and after the incident.

The aftermath of certain tragedies will and can have long-lasting psychological and physiological impacts on police officers. In addition, police officers attempting to maintain security and restore normalcy, even if not involved in responding at first to a tragic event, can experience vicarious trauma and stress-related symptoms. They, too, will be challenged to effectively manage their own symptoms and manage their own mental health.

Preparation for the Crisis

Stress from daily police work, if not managed and addressed, can have negative impacts on an officer’s longevity and productivity. Stress, whether from vicarious trauma and traumatization or cumulative stress related to policework, can lead to compassion fatigue, potential early career burnout, and a host of other stress-related diseases and illnesses.

Police personnel are exposed routinely to situations involving death; serious injury; and, at times, significant danger. In most U.S. police academies, police are trained to take steps to mitigate the risks of stress-related illnesses and diseases. Those who have built resiliency will be best suited to navigate and successfully manage themselves throughout their police careers.

However, in the face of a really tragic event, an officer’s resiliency can take one only so far, especially when encountering the fields of horror, pain, and heartache that accompany a mass casualty event. In addition, the duration and intensity of the aftermath will add to mental health pressures that already existed.

A crisis to an agency or a police officer can occur at any time. To be best prepared for any crisis and potential traumatic event, leaders must proactively develop skills, abilities, and relationships that can surpass the needs of a typical police response.

Police leaders must also proactively build agency resiliency and individual strength to withstand a potential crisis. Law enforcement leaders have to build a foundation of trust between police mental health service provides and the agency employees. That trust must be felt throughout the agency by both civilian and sworn staff. While in the throes of an emergent crisis is not the time to build trust with those mental health experts who will be available to help.

For smaller agencies, having police mental health providers within the agency or assigned to an agency may be difficult. Building trusting relationships with those mental health providers available within the community can go a long way in providing referrals and conduits to other providers who specialize in traumatic recovery and are familiar with treating police officers.

Police leaders must be willing to routinely communicate with all agency personnel to bring awareness and understanding to the importance of police mental health. Leading by example will go a long way in prepping personnel to accept mental health support when needed.

Law enforcement agencies can be very effective in the mental wellness arena when they develop resiliency training, mindfulness programs, peer support teams, and employee assistance programs (EAP). In addition, agencies can promote routine exercise programs and ongoing stress management skills training. Building for future crises and the associated mental health fallout should be the number one strategy for successfully navigating through a crisis.

Navigation after a Crisis

Many lessons have been learned from police leaders who have unfortunately experienced a crisis like a mass casualty incident. Not all agency executives will experience a mass casualty event in their careers. However, if they do or if they support another leader in navigating through a mass casualty incident, they will experience the array of new challenges and responsibilities that come with the event.

Agency leaders need to make important new decisions for the agency and lead the agency forward after the mass casualty crisis has concluded. The agency itself may have to re-define its mission in the short term because the needs of the community will have shifted. For instance, a relatively safe community, one in which there are not many homicides or serious assaults, may have to ramp up safety measures to enhance the idea of a safe and secure community for psychologically fragile community members. The law enforcement leader will be front and center in making these important cultural shifts within the agency and community.

Police leaders must be able to understand the uniqueness of the aftermath of a mass violence incident and be willing to hold themselves accountable for agency gaps in mental health strategies while also managing the incident’s aftermath. Lessons learned from past crisis events showcase the unique intensity of these events, which may astonish unsuspecting police leaders. However, the duration of the intensity has been what surprises most police leaders navigating the aftermath of a crisis.

Police leaders will have to manage intense and frequent media coverage and potential scrutiny of the agency response. They will be asked to bring some sort of normalcy to a chaotic situation; internally, they also need to lead important agency mental health decision-making. The police leader will be called upon to be very visible and very effective in communicating with community leaders, the community, the agency personnel, and their families. These two concepts—wellness and communication—may be the most important things a police leader does when navigating the post-crisis arena.

Wellness

When the unimaginable happens, police leaders will have to consider mental wellness support for their own personnel, civilian and sworn, and their families. Police leaders will have to sift through an array of mental wellness strategies and mental health providers, many who will self-deploy to the area. A mental health incident commander (sworn or civilian) can advise, share, and suggest mental wellness strategies with agency personnel, their families, and police leadership.

The agency leaders must be willing to lead by example and acknowledge the toll the event has taken on them. They cannot help others if they aren’t seeking help themselves. Police leaders must recognize their responsibility to mental wellness during a crisis begins with modeling the use of mental health services.

Police leadership will have to recognize the uniqueness of delivering mental health support to the agency while increasing the visibility of police officers in the aftermath. Time off for stress decompression will be a luxury. One useful strategy will be to offer paid time off to personnel without affecting any contractually protected paid time off. The agency can fill in necessary workload gaps with mutual aid partners if possible and necessary. Time off to be with family and loved ones can be a very effective healing concept and mental wellness policy.

Support from family, friends, and colleagues is an important part of recovery. Allowing for family time and personal time off will benefit the officer and their family. At the same time, allowing access to or encouraging family therapy will help the officer and family cope with the rigors of bridging life, work and family. Building family resiliency with officer resiliency should be among paramount concerns of the police leader.

If the agency has robust mental health protocols, programs, and policies in place, the implementation of them will be or should be seamless. Any peer-to-peer relationships, EAP resources, and existing relationships with qualified mental wellness and health providers will be the first line of mental wellness defense.

Police leadership must also emphasize that police officers take a personal interest in their own mental wellness. Allowing personnel to visit with their own mental health professional as often as necessary follows in this concept of personal interest.

Another important concept will be the aid an agency and agency leaders receive from mutual aid responders. In smaller agencies, the tasks and responsibilities in the aftermath can become overwhelming. If the agency leader has already developed strong ties with neighboring police agencies, then the trust to turn over certain critical responsibilities will be present. Navigating and managing the extra responsibilities during the aftermath of a mass casualty event will require an enormous amount of time and expertise.

Law enforcement leaders must recognize that the mass violence event itself will last a very short period of time, but the aftermath will last months and potentially years. To that end, leaders should be keenly aware of and build long-term officer and agency wellness plans and programs. Seeking out police mental health and wellness experts and other police leaders who have experienced similar events and may provide recommendations can help accomplish this goal.

There are many elements to consider when devising short-term and long-term psychological interventions. The strategies that are eventually implemented can be more acceptable to the agency, by bringing together the relevant impacted persons with the eventual service providers. Building a plan from the ground up may go a long way in building trust in the programs to be delivered. Decisions such as mandatory or involuntary post-care programs like critical incident stress management debriefings or tactical debriefings are best decided by qualified mental health and wellness professionals.

One of the aims of proper psychological post-crisis care is to limit PTSD symptoms and other stress-related diseases and illnesses. Police chiefs and administrators also have to consider the toll these events place on individual police officers and the early retirement or resignations that result from the event. Periodic mental health and wellness check-ins become useful tools immediately after the event and can become part of a long-term wellness plan. If the check-in is mandatory for the entire agency, the process shields those who may need or want the time with a provider from undue attention.

Communication

The police chief will have to be adept at informing and communicating with victims’ families as soon as possible following a mass violence event. Thereafter, formal meetings with impacted families are necessary to keep them apprised of the investigation, whether a suspect is in custody awaiting trial or the suspect has died. When possible, it is preferred that victims’ families hear relevant facts from investigators as opposed to finding out information from media outlets.

Assigning police officers or victim advocates to each family as a direct contact or point person will help victims’ families navigate their own aftermath after the tragedy. The assigned personnel can also become a source of comfort and offer protection from prying media sources looking for a different news angle.

As part of the multitude of additional or new tasks in the aftermath, the agency will have to maintain security perimeters for weeks or months, handle additional traffic details for well-wishers and self-deployed crisis response persons, manage curiosity seekers, fight off gift and donation fatigue, and effectively manage all media outlets. Police leaders will have to be extremely proficient at controlling the flow of information and may need to utilize additional public information officers for a period of time to address the many needs and requests of the media.

Successful Leadership through a Crisis

Police administrators are chosen to lead their agencies because they have certain innate qualities and skill sets that match the position an agency needs. When it comes to successfully managing a mass crisis event like an active shooter where many may die or be injured, the person responsible for public safety will be deeply challenged with the response and its aftermath.

Knowing what to do or what not to do is not always a given. The unique challenge for a police leader is coping with the unknown. The idea that a mass shooting event will happen to one’s community often seems remote and improbable.

If it does occur, there are steps that leaders can take to mitigate the fallout, especially when safeguarding the mental health and wellness of police staff. Having robust mental health programs such as peer support and an EAP and maintaining well-developed relationships with regional qualified mental health providers are key to successfully managing a mass crisis event.

Leaders will have to tap into and utilize known and trusted relationships for guidance, mentorship, and resources. The police leader, in times of the unimaginable, will have to maintain organizational integrity through compassionate decision-making and allow other leaders, formal and informal, within the agency, to step up where they are needed.

Finally, successful leadership through a mass violence tragedy, especially in the realm of mental health and wellness, requires that leadership places a priority on the health of the officers, staff, and families. Placing their wellness needs front and center, with frequent and honest communication of available wellness resources, will establish the importance the agency places on individual health. d

Please cite as

Michael Kehoe, “Accountable Crisis Leadership,” Police Chief Online, October 25, 2023.