Image courtesy of Breanna Moore, Michigan State Police

There is a growing concern about an erosion of trust in society today. Trust is a fundamental component of social and economic interactions, and diminished trust can have significant consequences for individuals, organizations, and the wider community. Many factors have contributed to the erosion, but the outcome is a profound distrust of institutions, governmental organizations, corporations, public service agencies, the media, and even one another.

A Crisis of Trust

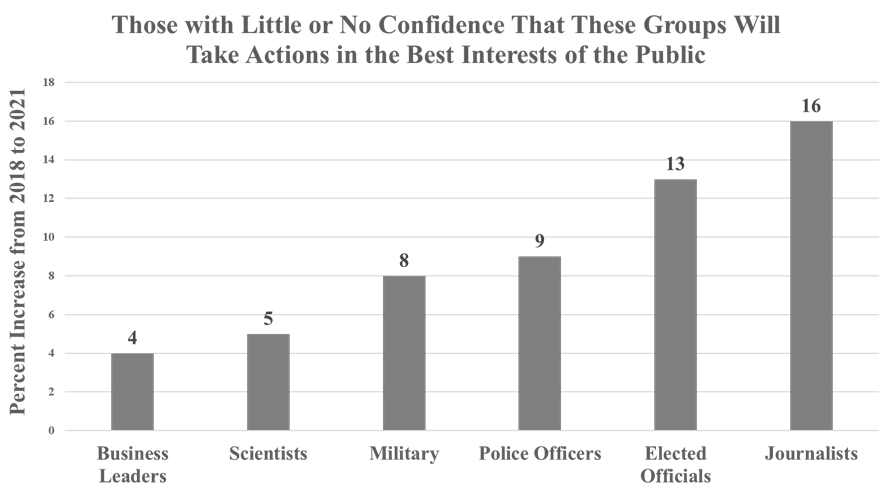

Many polls verify that a crisis of trust currently exists in the United States. As an example, Figure 1 shows the results of an ongoing survey conducted by the Pew Research Center looking at how the confidence of U.S. respondents has changed from 2018 to 2021.1 The Pew data reveal a dramatic increase from 2018 to 2021 in the percentage of those who have little or no confidence that the groups shown—business leaders, scientists, military, police officers, elected officials, and journalists—will act in the best interests of the public.

|

| Figure 1: Percent increase from 2018 to 2021 in those reporting little or no confidence that the groups shown will take actions in the best interest of the public |

Of the six groups or professions shown in Figure 1, police officers were among the top three for whom the largest increase in public distrust occurred. From 2018 to 2021, there was a 9 percent increase in those who reported little or no confidence police officers would take actions in the best interest of the public. This distrust for the police in 2021 was voiced by about one out of every three respondents to the survey (31 percent).2

The erosion of public trust has significant implications for many aspects of society, including in the economy, in politics, and for social cohesion. Without trust, it becomes difficult to cooperate, collaborate, and build relationships with others, leading to increased conflict and division. Distrust of the police is especially problematic inasmuch as this group is entrusted with the protection and care of the public. Too often in recent years, there have been instances of police officers relying on excessive force to carry out their mission. When this occurs, not only do they betray the public’s trust, these officers also undermine their sworn duties to protect and serve. Addressing the current crisis of trust throughout society is not an impossible task, but it will require a multifaceted approach that must involve strengthening agencies, institutions, and organizations by improving their transparency and accountability, as well as by promoting greater honesty and fairness in their communications. Achieving these kinds of changes will necessitate making dramatic shifts in the internal culture of most agencies, institutions, or organizations.

To this end, two important internal culture-change initiatives are currently underway within the Michigan State Police (MSP) that may offer a path forward for helping to resolve the crisis of trust, not only with respect to public confidence in policing, but also with respect to the trust employees in a policing organization have for one another and for their leaders.

TrustBuilder

The first MSP initiative, a program called TrustBuilder, was inspired by the work of a nonprofit organization known as The Curve Initiative.3 The Curve aims to modernize policing by bringing the most current and creative ideas about leadership and organizational culture change to forward-thinking leaders in policing so they have the tools needed to create a thriving culture in their agencies and organizations.

TrustBuilder is founded on the fact that trust is a bond between two parties—one who is granting trust and the other to whom trust is bestowed. Those who grant trust want to believe in the abilities and intentions of those being trusted. In order for a bond of trust to arise, the person granting trust must be willing to give it—and the person receiving trust must be worthy of that trust. There is a simple relation between these two elements of trust called the “Trust Equation.”

Trust = Trust willingness X Trustworthiness

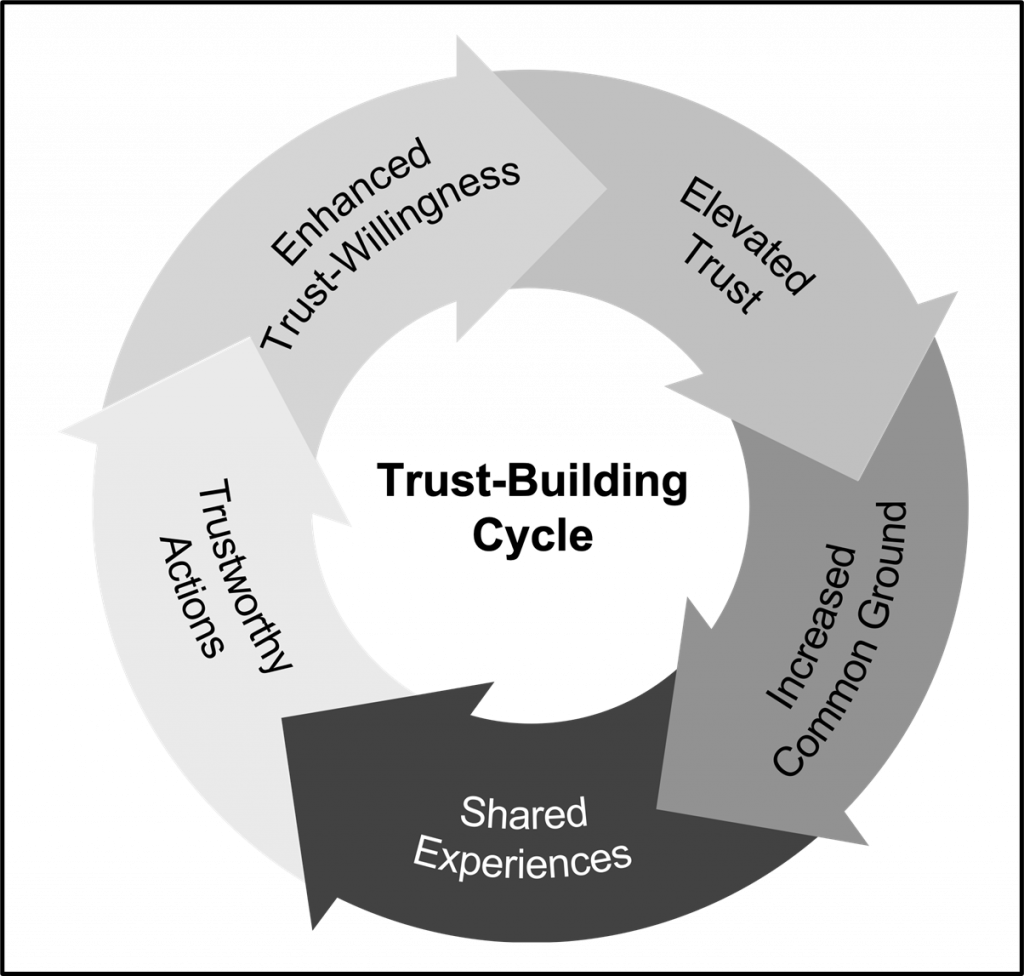

This equation says that both elements must be non-zero in order for trust to occur. If either element is zero, then trust is zero. Also, this equation implies that trust is higher when both elements are high. The two elements in this equation are interdependent in a particular way: the more a person to be trusted demonstrates trustworthiness, the more the person granting trust becomes willing to trust. This interdependence gives rise to the trust-building cycle shown in Figure 2.

|

| Figure 2: The trust-building cycle showing the interdependence of trustworthiness and trust willingness. |

The cycle in Figure 2 often starts with the person being trusted and the person granting trust having shared experiences such as common struggles, goals, or purposes. These shared experiences are a form of common ground that is a necessary precursor to the trust-building process. Shared experiences allow the person or group granting trust to be receptive to the trustworthy actions of the other person or group, which when they occur, enhance trust willingness and elevate trust between the two parties. Elevated trust, in turn, increases the common ground between the two parties, strengthening their shared experiences, thus allowing the cycle to continue.

In the TrustBuilder program, the trust-building cycle is activated by bringing small groups of police leaders and employees together in a collection of teams, each of which is empowered with a common purpose: develop a solution to meaningful organizational challenges currently being faced by their organization. The shared purpose for which teams are brought together initially creates a form of common ground that kick-starts the trust-building cycle. The members of each team have direct experience with one another’s character and competencies, which are primary ways of demonstrating trustworthiness.4 Another key factor here is the solution empowerment granted to teams, which creates a sense of agency that participants may not experience regularly in the normal course of their work life. This agency helps to foster the shared belief within teams that they can and will solve important problems, which further strengthens their bonds of trust. Finally, the method by which teams are encouraged to formulate solutions involves gathering input from others in the organization who are affected by the challenges being addressed, and then identifying and testing potential solutions to those challenges. This method creates a kind of scientific mindset to problem-solving that is both logical and data driven. All of this fuels the trust-building cycle within each team, which allows the team members to develop a strong sense of confidence in their individual and collective abilities, leading to exceptionally highly performing teams.

TrustBuilder takes participants within each team on a three-month learning and leadership journey through several stages:

-

- Team building and learning how to work effectively with one another

- Interviewing organizational stakeholders who are affected by the identified challenges

- Generating ideas about possible solutions to address the challenges

- Selecting a solution and pilot testing it

- Developing a compelling presentation on the solution tested—including the pilot results

These stages lead up to a culminating event called an Idea Fair, in which teams showcase their solutions and present proof-of-concept data from pilot projects in front of organizational leaders and other invited guests. In each stage of this journey, the teams profit from just-in-time training relevant to the goals of each stage, along with guidance and support from experienced TrustBuilder coaches.

First Wave

The first wave of TrustBuilder is now complete at MSP with nearly 75 participants and seven teams. Six of the teams were composed of various employees who work in the field or in other capacities within the organization. The challenge opportunity driving each team’s work was to develop the United States’ most modern police culture built on exceptional customer service. Each team was empowered to propose a solution relevant to this opportunity and proceeded through the stages noted above.

The seventh team, composed of executive leadership from MSP headquarters, was assigned to lead and manage the individual workflows needed to make TrustBuilder work. There were five workflows: strategy, development, operations, communications, and events. A steering committee, made up of a designated MSP leader from each workflow, acted in an oversight capacity. Also on the steering committee and assigned to the workflows were members of a broader team from the private sector who have been involved in TrustBuilder implementations outside of MSP. The value of having MSP leaders work hand in hand with private sector executives and other experienced TrustBuilder team members has been immeasurable. The guidance and advice provided by external TrustBuilder partners not only makes implementation smoother, it also helps to ensure program longevity by making TrustBuilder a program MSP “does to itself” rather than something that is being “done to MSP.”

Another important aspect of MSP’s external partnership with the private sector TrustBuilder team comes from the coaching support the external members provided to the six employee teams as they were working on challenge solutions. Each of these teams had a pair of designated co-leaders from MSP who oversaw and directed team activities. However, in the first wave of TrustBuilder, those co-leaders had no real experience with the process. To address this deficit and facilitate the development of the MSP co-leaders, each team was assigned an external coach from the private sector who was an experienced TrustBuilder team leader. These coaches mentored their assigned co-leaders in each stage of the process and also brought a fresh and unbiased perspective to the traditional MSP policing culture. The resulting dynamic has been quite beneficial to MSP as external coaches have asked questions about why things are done in certain ways, have shared their own perspectives on leadership strategies, and have shared examples of solutions they have seen teams develop in other industries. The cycle of trust building described previously was clearly at work here as MSP co-leaders and team members discovered their common ground with the external coaches, observed the trustworthy behavior of the coaches, and came to trust them as valued partners and guides in an unfamiliar process. Historically, this type of engagement with outside parties is an uncommon and challenging experience for the policing industry. However, the result has been the development of MSP co-leaders who are now ready to be coaches themselves in future waves of TrustBuilder within MSP.

Outcomes

Those who have participated in the TrustBuilder process have experience positive outcomes such as

- enhanced networks, innovation, and team performance;

- measurable increases in reported trust, engagement, and morale; and

- positive personal and professional development experiences.

Organizations using TrustBuilder also benefit from the solutions the teams develop, increased employee loyalty and retention, and the opportunity to see their top talent in action at the Idea Fair.5

Although three-quarters of first-wave participants felt that the program involved more work than they originally expected, many positive outcomes were reported on a post-wave survey:

- All participants said TrustBuilder improved their trust of colleagues.

- Most (94 percent) said their trust of leaders improved.

- Almost all (98 percent) said their teamwork improved.

- Most (94 percent) said their problem-solving improved.

- Almost all (98 percent) said their overall skills and knowledge improved.

- Many (87 percent) said their ability to do their job improved.

- Many (80 percent) said they would recommend the program to a colleague.

These aggregate reports were accompanied by many personal comments about how individuals benefited from the program, including the following examples:

- “I think getting us out of our comfort zone is always a way to grow. Forcing us to share input and work on communication and presentation skills as well is also beneficial.”

- “[A benefit was] meeting and trusting new people—starting as strangers and becoming friends to reach a goal working together.”

- “Making connections while finding solutions was highly impactful.”

- “This program solidified the following for me: Relationships are important. Listening is important. Everyone brings value.”

- “Thank you for this opportunity. This type of access and growth keeps me engaged in the department.”

The challenge solutions proposed by the six first-wave teams represented an impressive array of ways in which MSP ultimately could improve internal customer service, ranging from projects devoted to enhancing the mental and physical well-being of MSP personnel, to initiatives aimed at providing better and more timely training, to plans designed to achieve better representation of employees in agency decision-making and increased employee interaction with agency leadership.

Input from first-wave participants also provided valuable suggestions for improvements that could be made in successive waves in areas such as communications, scheduling, and deployment of development resources.

A recurring theme among first-wave participants was that, prior to TrustBuilder, they had felt comfortable with their current professional roles being on “cruise control.” Following TrustBuilder, however, many participants felt they had a renewed sense of contribution, voice, problem-solving capabilities, growth, and leadership within the MSP. All of these outcomes represent important cultural changes that directly support the second key initiative underway at MSP.

Modern Policing

The second initiative is a variation of what is called “Modern Policing,” a movement based on the growing awareness that it is time to re-think and reexamine the methods and best practices used by agencies entrusted with maintaining public safety and security.6 At MSP, the Modern Policing initiative focuses on the key areas of culture, accountability, learning, and innovation in service of a “just cause” or the “why” behind everything they do, which is to “help build a Michigan where everyone feels safe and secure.”7 Modern Policing recognizes that the only environment an agency can control is its own. Accordingly, an agency must focus on creating the most positive and principled culture it can within its own organization for officers to absorb and reflect outward to the public.

The positive and principled culture at MSP, aided by the positive influence of the TrustBuilder program, is based on the following nine important tenets, which when absorbed internally and then reflected outwardly, will be instrumental in fulfilling the just cause of enhancing Michigan’s safety and security and enhancing public confidence in policing.

-

- Focusing on customer service at all times, recognizing that each interaction with a citizen is an opportunity to be transformational, not just transactional

- Treating everyone with dignity and respect, exercising the human skills of empathy and compassion

- Holding each other accountable to the mission

- Promoting full transparency, both within the agency and for the public

- Working with the communities it serves to develop authentic connections and to meet real community needs

- Providing its members with continuous learning and professional development opportunities

- Recognizing and preparing police officers to perform the dual role of protector and warrior when necessary and appropriate

- Using research-based and data-driven methods to address challenges like racial and ethnic disparities in traffic stops, or sensitive topics

- Adopting recruiting and hiring practices leading to a workforce that reflects the communities being served

By adhering to these nine tenets, the leaders, enforcement personnel, and professional staff of the MSP believe they can transform how policing is done in Michigan with many positive benefits both within their own department as well as within the communities they serve. For example, MSP employees report that the increased focus on customer service and respect gives them a new perspective on their jobs that allows them to see beyond their traditional enforcement roles to other support, assistance, and educational roles they can play within the communities they serve. Moreover, employees believe these tenets increase the pride they have in their jobs and their organization. These outcomes are incredibly important in light of recent events that have cast considerable doubt and suspicion on the policing profession.

Relation of Trust Building to Modern Policing

Among the many benefits of widespread adoption of the Modern Policing principles currently being used by MSP will be a substantial elevation of public trust in society for policing agencies and law enforcement personnel. The reason trust will be elevated when Modern Policing tenets are put into widespread use is because of the way in which the actions behind these tenets overlay on the key action categories previously identified as being of critical importance to demonstrations of trustworthiness.8 As discussed elsewhere, the action categories particularly relevant to trustworthiness are

- showing respect for others;

- being accountable to self and others;

- living out core values;

- promoting joy, safety, and recognition; and

- achieving competence.

The TrustBuilder program takes advantage of these action categories as teams come together to share their direct human connections. As previously noted, this shared experience, together with their common purpose, fuels the trust-building cycle as team members see clear demonstrations of trustworthiness in one another. As the trust-building cycle and the trust equation suggest, elevating trustworthiness will elevate trust willingness and increase trust.

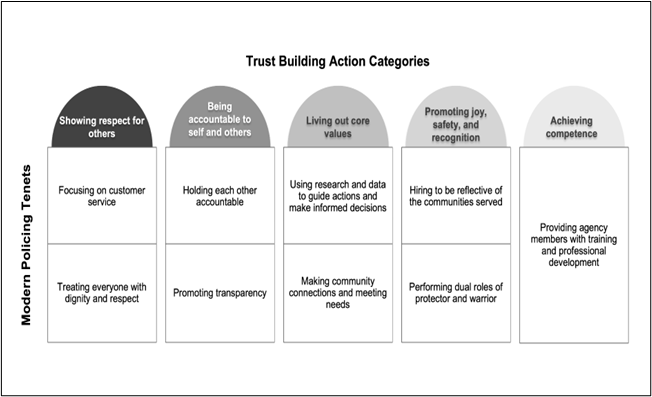

Interestingly, there is a clear relation between the action categories relevant to trustworthiness and the actionable tenets of Modern Policing currently in use at MSP, as shown in Figure 3.

|

| Figure 3: The relation of key trust-building action categories to the tenets of Modern Policing in use by the Michigan State Police. |

This figure shows that each of the nine Modern Policing steps fit squarely within the action categories of trust building. Modern Policing will accelerate the trust being created within the TrustBuilder teams at MSP and will also serve as clear demonstrations of the trustworthiness of MSP personnel to the public in the Michigan communities they serve.

Conclusion

The crisis of trust is real and needs to be addressed. MSP is taking steps to meet this crisis head on, not only within its own agency, but also within the general public through the use of actions that advance justice and inspire public trust. Nothing could be more trust inspiring to the public than witnessing the MSP acting in a clear and decisive way to build a safer and more secure Michigan for its residents.

As noted above, MSP also has recognized it can benefit greatly from partnerships with other agencies, organizations, and economic sectors. The benefits to the MSP TrustBuilder initiative of the previously described partnership with personnel from the private sector are very clear and compelling. Likewise, as noted, the Modern Policing initiative within MSP is grounded in the work of The Curve.9 These types of interorganizational partnerships may spark the kind of innovative thinking needed to address the trust crisis in a significant way.

TrustBuilder offers a perfect structure for bringing the community together with policing agencies in the form of hybrid community-police teams throughout the state. This effort would be both a logical extension of TrustBuilder and Modern Policing. These teams would bring community leaders and MSP members together for mutual learning and educational opportunities, idea generation, and problem-solving related to important community needs. Having MSP personnel work in concert with community members in this way would fuel the cycle of trust building with the community, thereby addressing the crisis of trust head on. The resulting renewed community-police relationships from such a partnership would be reward enough, but the innovation that also could result is limited only by imagination.

It is hoped that as other agencies witness the many positive current and future outcomes of the TrustBuilder and Modern Policing initiatives underway at MSP, they, too, will be inspired to adopt these approaches as best practices in their own organizations. These initiatives at MSP model the kind of innovation that thought leaders tell us will become infectious once the benefits of that innovation become more widely known.10 🛡

⸻

Notes:

1Pew Research Center, “Public Confidence in Scientists and Medical Scientists Has Declined Over the Last Year,” February 14, 2022.

2Pew Research Center, “Public Confidence in Scientists and Medical Scientists Has Declined Over the Last Year.”

3Charles R. Crowell and Patrick Berges, “The X-Factor in Trust,” 2013; The Curve website.

4Crowell and Berges, “The X-Factor in Trust,” 2.

5Crowell and Berges, “The X-Factor in Trust,” 7–8.

6The Curve website.

7Joe Gasper, “Gasper: Modern Policing Means Principled Understanding of Enforcement,” Opinion, Detroit News, March 13, 2023.

8Crowell and Berges, “The X-Factor in Trust,” 3–6.

9The Curve website.

10Simon Sinek, “Navigate and Embrace Change,” YouTube video, 4:32, October 15, 2021.

Please cite as

Joseph Gasper, Patrick Berges, and Charles R. Crowell, “Addressing the Trust Crisis: Trust Building and Modern Policing within The Michigan State Police,” Police Chief Online, September 27, 2023.