After the September 11, 2001, attacks, the mission, focus, and culture of the FBI shifted to reflect a new top priority: preventing acts of terrorism. This shift to a more proactive and prevention-based approach meant making significant legal and structural changes within the U.S. government to improve information sharing among intelligence agencies. It also meant working to improve communication and collaboration with law enforcement partners through the FBI’s Joint Terrorism Task Forces (JTTFs) and other partnership efforts.

Along with organizational changes and a cultural shift toward more fluid information sharing and collaboration came the understanding that preventing terrorist acts required a change in investigative strategy. The FBI needed new and creative methods to identify threats as early as possible because the earlier threats were identified, the more likely coordinated efforts could be applied to prevent violence from occurring.

The FBI’s Behavioral Analysis Unit 1 was established to support prevention through the application of behaviorally based operational support, training, and research. Over the years, the unit has evolved into the Behavioral Threat Assessment Center, a multiagency, multidisciplinary task force that provides investigative and operational support for the FBI’s most complex, concerning, and complicated terrorism investigations.

While the threat of long-term, sophisticated attacks by organized terrorist networks persists, the unit is also seeing a rapidly developing, technology-amplified threat from individual actors who are motivated by a broad spectrum of ideologies.

The factors driving a potential attacker from thought to action are highly personal and often a complex combination of both personal and ideological factors. Would-be attackers are inspired by and, in some instances, competing with other attackers for attention and notoriety, regardless of commonalities or differences in their motives. Personal interaction is no longer required for potential offenders to find like-minded individuals, glamorization of prior attacks, or inspiration for future attacks. Complicating matters, technology has also greatly enhanced the ability for attackers to control the delivery of information and the messaging related to their attacks.

To address this troubling trend, the Behavioral Threat Assessment Center’s (BTAC’s) work has expanded to provide threat assessment and threat management support beyond the JTTF-led terrorism investigations to the law enforcement partners and community stakeholders who are working diligently on targeted violence prevention.

The BTAC has found the team’s experiences and lessons learned from its efforts to prevent acts of terror have informed its approach to preventing targeted violence. Targeted violence is a widespread but often localized threat; therefore, the tools for identifying, sharing, assessing, and managing threats can and should be implemented in every police department and every community.

A Shift in How to Identify Threats

To be truly effective in prevention, the early identification, recognition, and reporting of concerning behavioral information are critical.

Historically, identification efforts for threats emanating from overseas terrorist organizations relied on traditional U.S. intelligence community sources and methods. Other threat identification methods, such as the See Something, Say Something campaign rely on strangers and passersby to recognize and report suspicious activity.

Research and operational experience, however, have shown that those closest to offenders (e.g., family members, peers, and friends) are often in the best position to recognize and put into context concerning behaviors that may indicate radicalization and potential mobilization to violence. Further, this group of bystanders is also in a position to recognize concerning behavior early in the mobilization process, thus allowing more time for prevention.

In November 2019, the FBI published the Lone Offender Terrorism report, which examined 52 ideologically motivated lone offender terrorist attacks conducted in the United States between 1972 and 2015.1 Prior to that, in June 2018, the FBI published A Study of the Pre-Attack Behaviors of Active Shooters, which examined the pre-attack behavioral indicators of 63 different active shooters in the United States between 2000 and 2013.2 Both of these reports concluded that, while the motivators and drivers for violence are highly individualized, those who commit violence travel an observable and discernable pathway from thought to action.

Research and operational experience also reveal that ideologically motivated lone offenders and active shooters were rarely completely isolated while they traveled down the pathway to their ultimate acts of violence. The research shows that, in most cases, multiple people who had contact with each offender observed concerning behaviors.

The encouraging message in that research is that terrorism and other acts of non-ideologically motivated targeted violence can be prevented if the public is taught to recognize and report concerning behaviors, regardless of ideology or identified motive, they observe in friends, family members, peers, coworkers, and others. Not surprisingly, however, those closest to the person of concern are often the most resistant to reporting information to law enforcement.

For this reason, law enforcement is not always the most logical or the most likely agency to intake such information. In many situations, the initial reporting of concerning behavior will be made to non-law enforcement authority figures, such as a school counselor, a coach, or a local religious leader. As such, community members need clear and sometimes multiple avenues for potential reporting. It is crucial, however, that law enforcement become a part of the assessment and management of any credible threat.

Handling Tips and Information

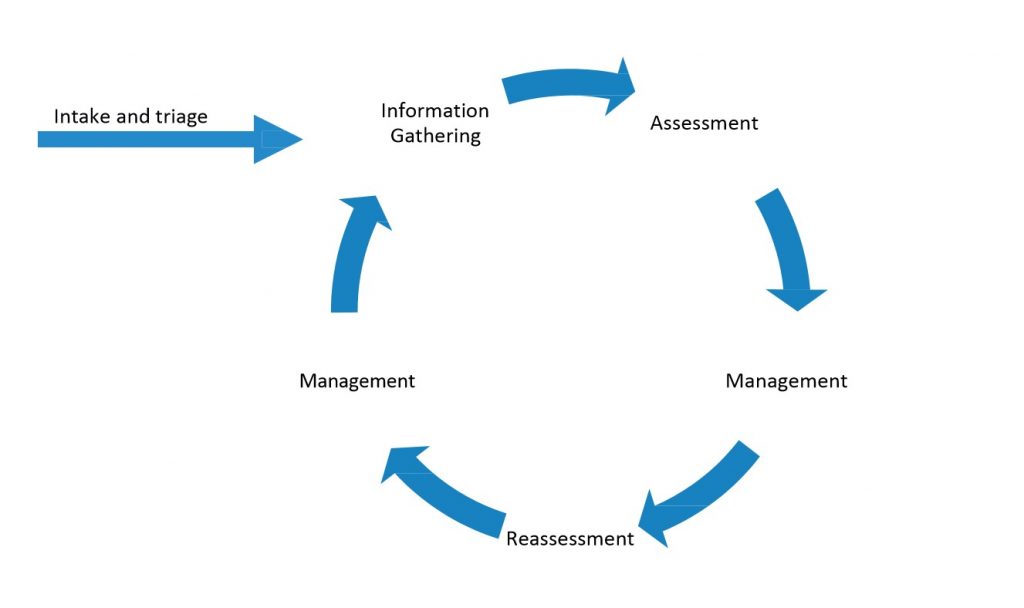

A tip concerning a threat connected to an ideology or terrorism is very likely to be referred to a JTTF and worked in a manner consistent with the tried-and-true integrated team approach. The process is less clear for what may be an equally significant threat of non-ideologically motivated targeted violence.

For example, a report about a student exhibiting concerning behaviors without a clear connection to terrorism or violation of state law (e.g., no direct threat is made) might be entirely addressed by non-law enforcement entities, such as school administrators or counselors. In this scenario, critical decisions about threat assessment and threat management are being made by stakeholders largely unfamiliar with law enforcement capabilities and without the vast, significant body of information and experience law enforcement can contribute to the process. These limitations can significantly limit prevention efforts.

Similarly, it is incumbent upon those managing intake mechanisms to ensure individuals receiving and triaging the information have training in and familiarity with the concepts of terrorism and targeted violence. Intake mechanisms without basic threat triage capabilities are counterproductive and risk enhancing and should not be promoted or relied upon.

The Need for Additional Information

Initial reporting is by its nature often limited in scope and context. It is often only a single person’s perspective, and clarity about the threat comes only through the gathering of additional information. Research and operational experience have shown there is no one demographic profile of a potential terrorist or active shooter, there is no checklist to determine which cases are worthy of investigation and which are not, and there is no scoring algorithm to predict potential attackers. Therefore, to the extent possible, law enforcement agencies and other intake mechanisms should endeavor to gather additional information about the potential threat to better assess the threat and the need to escalate to a more structured and formalized investigative and information gathering process.

Should it be determined during intake and triage that additional investigation or information gathering is required, the question then becomes by whom? As mentioned above, when terrorism threat leads are received, the initial threat information is routinely disseminated to a JTTF (or in some cases dual-routed to a fusion center) where additional basic information can be gathered to get a better assessment of the threat. In a similar way, initial threat leads that are received and meet minimum triage thresholds should be referred to an entity with the training and authority required to investigate or gather additional information to make a better assessment of the threat. For example, additional information, particularly open-source information readily available online, can provide valuable context to assist in the evaluation of potential threats.

Threats of targeted violence or reports of persons of concern are, by their nature, potential law enforcement or criminal matters, and to the extent possible, law enforcement should be included in the initial investigation and information gathering phase. Law enforcement, training, experience, and investigative authorities greatly enhance the initial threat assessment process. For example, a school threat assessment team dealing with a challenging student of concern would benefit greatly from learning about law enforcement’s contact with the student outside of school hours or reports of concerning behavior made independently to law enforcement and not to the school. A primary focus at this point should be on determining the credibility, imminence, and significance of the threat. Certain threats require immediate action. Others can be more effectively mitigated through additional information gathering and sharing and collaboration.

Often, multiple entities in a community could be trying to assess a person of concern without the benefit of the information held by others. School systems, mental health counselors, local police, and the FBI could all have small pieces of information that, if put together, would provide the clarity needed to help effectively resolve the threat. Similarly, and perhaps just as significantly, these same entities, operating in a vacuum, could take action without consideration for another or bigger threat and the potential second- and third-order consequences of action by one entity uncoordinated with the others. Just like a “unity of effort” was required following 9/11 to prevent acts of terrorism, so too is a unity of effort needed to prevent acts of targeted violence.

Information sharing between these entities, while critical to prevention, is appropriately limited in the United States by legal restrictions such as the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA) and Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) Privacy Rule. It is therefore important for all stakeholders involved in prevention to know that there are exceptions to HIPAA and FERPA that allow information sharing with law enforcement in situations where threats of violence exist.

Similarly, there are exceptions to standard privacy and civil liberties restrictions for information held by law enforcement. Sometimes, information can be shared only in one direction—from mental health to law enforcement or from law enforcement to mental health—but the key principal is that information should be shared as much as legally possible so the different stakeholders working on the assessment can have a comprehensive context.

Establishing a Threat Assessment and Threat Management Team

|

Threat Management Team Members A threat management team can include representatives from:

|

Although one model will not fit every community, a multidisciplinary threat assessment and threat management (TATM) team can be an effective model for building the information sharing and collaboration structure necessary to prevent acts of targeted violence.3 TATM teams are scalable to work for an individual school, a school district, a county, region, or state. TATM teams need only to have the right training and the right mix of people working together to evaluate, investigate, assess, and manage threats. Ideally, these TATM teams have the ability to reach out to others for help when the challenge of the situation exceeds the initial TATM team’s capabilities, experience, or geographical jurisdiction. Just as the threat of terrorism cases cross jurisdictional and geographical boundaries, so too do threats associated with targeted violence.

In addition, TATM teams should have the ability to involve key players from across disciplines and areas of expertise, to include law enforcement, community mental health, social services, education, probation and parole, prosecutors, and judges. TATM teams can operate with a small core of key players while maintaining the ability to bring in other stakeholders depending on the situation.

Threat Management

Effective threat management is driven by accurate, structured, holistic, and robust assessment. Sometimes law enforcement tools and actions are the most effective and appropriate threat management options available. At other times, law enforcement options are not available or they are not the most effective threat management option. TATM teams can help in identifying the full array of possibilities for the management of each threat and can coordinate response across agencies and disciplines. For example, a student who has been identified as moving along the pathway to targeted violence, but who has not yet violated the law may be effectively (or temporarily) managed through non-law enforcement methods while law enforcement continues to monitor the situation and gathers additional information about potential criminal violations. Throughout the management process, the effectiveness of non-law enforcement management should be closely monitored and adjustments made as the situation evolves.

Depending on the significance and imminence of the threat, immediate mitigation might be required. This form of immediate mitigation can take many forms, including but not limited to law enforcement actions, mental health crisis response, expulsion from school, or firing from employment. It is important to recognize, however, that such actions, while absolutely required by the situation, do not always fully or effectively mitigate the long-term threat associated with a person of concern. In reality, for certain situations, the immediate actions taken by one entity may ultimately cause longer-term threat implications. Therefore, it is important that TATM teams consider and assess the potential second- and third-order consequences of threat management decisions. In addition, while certain threat management options may work for the short term, it is important that TATM teams build into their process or framework the ability to follow up on potential threats to ensure the threat hasn’t remained or become enhanced.

The Evolving Role of the FBI Threat Management Coordinator

Recognizing that the challenges of threat management can be addressed only through a whole-of-community response, the FBI is diligently working to develop new and meaningful partnerships across all levels of government and within the communities the FBI serves. In addition to existing task force and liaison relationships through FBI field offices and divisions, the FBI has historically relied on a cadre of 270+ Behavioral Analysis Unit coordinators who are assigned to all 56 field offices and divisions.

Recognizing a need for even more robust partnerships and coordination on these complicated topics, the FBI has created a new position in the field called the threat management coordinator. These threat management coordinators are charged with working within their individual FBI field offices to identify and establish a relationship with existing law enforcement TATM teams in the area.

In addition, the FBI’s threat coordinators can provide training and help identify key stakeholders within their regions who may be able to assist in the assessment and management of threats or be incorporated into a TATM team.

FBI Training on TATM for State and Local Partners

The FBI is in the process of rolling out TATM training for state and local task force officers currently assigned to FBI field offices and divisions. The first class is scheduled for September 2020 and will include 100 strategically selected task force officers from across the United States. Moving forward, the FBI threat management coordinators will work collaboratively with state and local task force officers to create effective, tailored, and appropriate regional teams.

Additional information on FBI’s Behavioral Analysis Units, the BTAC, and the enhanced threat assessment and threat management efforts can be found by contacting the local FBI field office and asking for the Behavioral Analysis Unit threat management coordinator. Similarly, the FBI’s BTAC stands ready to assist its law enforcement partners on particularly concerning, complex, and challenging threat cases.

Through these efforts, the FBI is looking to identify those key partners with whom it can collaborate on threat cases and share information to help protect our communities in a way wholly consistent with federal law, policy, and guidelines. The FBI is not trying to assume additional non-federal law enforcement responsibilities but rather support communities in identifying threats and preventing violence. The FBI views closer collaboration with state and local partners as critical to violence prevention. d

Notes:

1 National Center for Analysis of Violent Crime, Lone Offender: A Study of Lone Offender Terrorism in the United States (1972–2015) (Washington, DC: FBI, 2019).

2 James Silver, Andre Simmons, and Sarah Craun, A Study of Pre-Attack Behaviors of Active Shooters in the United States Between 2000 and 2013 (Washington, DC: FBI, 2018).

3 Molly Amman et al., Making Prevention a Reality: Identifying, Assessing, and Managing the Threat of Targeted Attacks (Washington, DC: FBI, 2017).

Please cite as

John Wyman, “Applying Counterterrorism Tools to Prevent Acts of Targeted Violence: Lessons Learned from the FBI’s Behavioral Threat Assessment Center,” Police Chief Online, June 10, 2020.