For police chiefs considering the addition of a social media manager position or wondering about the actual value of an agency social media program in the first place, new police-specific research sheds light into the benefits of dedicating resources towards employing a two-way engagement strategy.

While “engagement” is an exceptionally common buzzword tossed about freely when discussing law enforcement and social media, many police agencies use social media only as a “digital bullhorn,” —just another one-way communication channel used to push information out to the public. That is not engagement. In order to leverage the true power of social media as recommended in the U.S. Department of Justice’s Final Report of the President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing , agencies need to dedicate time and energy to being responsive on social media, engaging in regular, two-way, back-and-forth conversations.1

Police executives benefit from police-specific quantifiable data to inform staffing decisions, not the anecdotal, vague recommendations of self-appointed experts. Chiefs need facts to support the concept that there is a benefit to spending time and resources on engaging with the community in a two-way manner While research is robust on topics like two-way engagement, the benefits of having a large followership on social media, and the positive impact a government agency can make by using social media in the aftermath of a crisis, there has been a marked lack of police-specific quantifiable data in the field of law enforcement social media that shows the benefits of two-way interaction.

In an attempt to fill that gap, this author conducted extensive police-specific research into the value of two-way engagement on Twitter as part of his master’s program at the Naval Postgraduate School. Using an evaluative research paradigm, the author studied the Twitter two-way engagement practices of three mid-sized agencies in the Silicon Valley region of California (the Santa Clara Police Department, the Mountain View Police Department, and the Palo Alto Police Department) over the course of a six-month period. More than 1,600 tweets sent by the three agencies were analyzed, as were more than 350 tweets sent by other users to the agencies (and to which the agencies replied), with a descriptive coding method used to sort tweets into specific categories.2

The research revealed that agencies using a two-way communication model receive more new followers overall than agencies using a one-way model. Why is the number of followers so critical? The more followers an agency has on Twitter, the more people who receive the agency’s message in its own words, unfiltered, and without the “spin” of another intermediary such as the mainstream media. Instead of getting the news from the media, followers instead can receive accurate, critical public safety information directly from the agency itself. Therefore, if a two-way communication model can contribute even in a small way towards building an agency’s follower base, it may be worth the cost of staffing. The research also revealed a number of tactics that police agencies can use to increase their level of two-way engagement on Twitter.

What the Data Actually Show

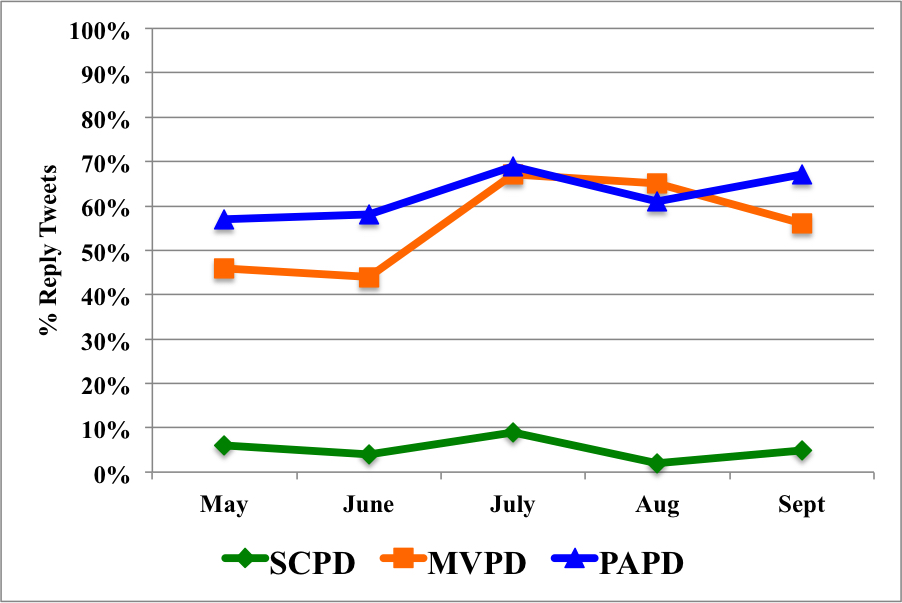

Determining whether an agency uses a two-way communication model is as simple as looking at the percentage of their total tweets that are replies to other users. During the study period, 62 percent of the tweets sent by the Palo Alto Police Department and 51 percent of those sent by the Mountain View Police Department were replies, whereas only 2.9 percent of the Santa Clara Police Department’s tweets were replies.3

The two agencies using a two-way communication model received more new followers than the agency employing a one-way communication model. During the study period, the Mountain View Police Department received 82 percent more followers than the Santa Clara Police Department, and the Palo Alto Police Department received 28 percent more followers than the Santa Clara Police Department.4 It is acknowledged that there are a nearly endless number of variables that could contribute to these numbers, other than just two-way engagement.

All original tweets sent by the agencies were grouped into one of eight categories according to subject matter. In the case of each of the three agencies in the case study, the public wrote reply tweets most often to the same three categories: community policing, static news (e.g., press releases, police blotter entries, and advisories about future events), and real-time news (e.g., breaking news or a real-time traffic advisory).5 These topics seemed to generate conversation. On the other hand, tweets containing crime prevention messages or those soliciting the community’s help to locate a criminal suspect received far fewer replies from the public.

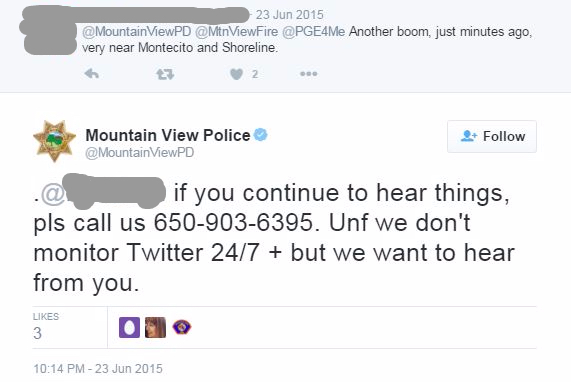

Many users sent tweets to the police agencies for various reasons; this is the Twitter equivalent of calling the police to communicate a concern, ask a question, or otherwise express an opinion. While all three agencies studied received such self-initiated inquiries from the public, the two agencies employing a two-way communication strategy responded to many more of them. Most frequently, these tweets asked a question of the police (for example, “What’s happening at First and Main right now?”) or complained about a crime or traffic problem. The agencies most often responded to a question by providing an answer to the question in a tweet and most often responded to a crime or traffic complaint by directing the user to call or email the police to provide additional details.6 During the study period, the three agencies responded to a total of 363 self-initiated contacts by Twitter users.7 These users could have instead called the police station, or dispatch, or even 9-1-1 to communicate their concerns or ask their questions. Instead, though, because the agencies were present and engaged on social media, the users received their response via social media. For agencies looking to increase opportunities for two-way engagement, responding to inquiries via Twitter is a fantastic way to demonstrate responsiveness, accessibility, and a willingness to engage with users in a way that all can see.

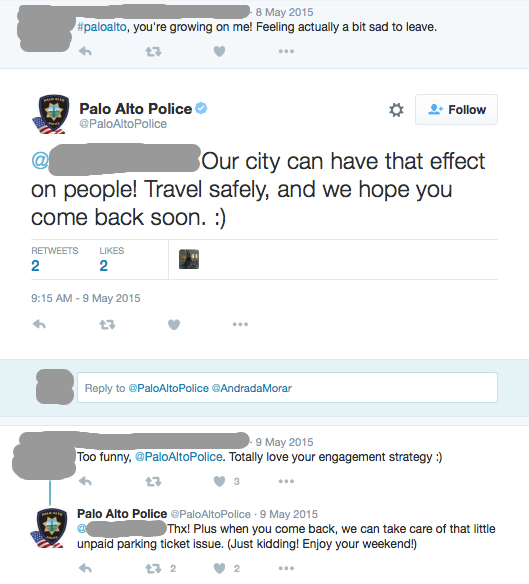

Next, the two agencies employing a two-way communication model routinely self-initiated reply tweets to random tweets by Twitter users. The user does not always need to be the one to initiate a two-way conversation; the police agency can do it too. The Mountain View and Palo Alto Police Departments often sent tweets to users that took the form of a conversational reply or other acknowledgement of the user’s tweets. This strategy potentially benefits the agency in a number of ways. First, it brings the user’s attention to the agency’s Twitter account and, in so doing, may generate a new follower. Next, the user may retweet the agency’s message to show their own followers the novelty of having a police department respond to them in a conversational manner. Lastly, it shows the user that the agency is active on Twitter, engaged with other users, and willing to initiate conversations online.

Finally, the research showed that for each agency, there were periods of exceptional follower growth where the department received many more new followers on a given day than was average. These periods were precipitated by events of public interest, which could be a notable arrest, a major call, a critical incident, or some other event that otherwise captures the public’s attention. Many of an agency’s tweets sent during such an incident are immediately retweeted by users, which greatly amplifies the reach of the agency’s message and also exposes the agency to a fresh set of users who may then become new followers. The agency essentially becomes the primary news source during these events, and new users begin to follow the agency to learn the latest accurate information.

Four Recommendations

Based on the data analyzed, the research concluded with a set of specific recommendations for agencies looking to increase opportunities for two-way engagement on Twitter.8 These recommendations are all things that someone in a social media manager position could easily implement. Four of those recommendations are included here.

First, agencies should tweet about community policing topics, static news, and real-time news. While users will reply to tweets on other topics, the research showed that users most frequently replied to tweets about those subjects. Every reply received is a chance for the agency to engage that user in additional conversation.

Second, agencies should take advantage of opportunities to live-tweet about major incidents in a timely manner, as these often will turn into periods of exceptional follower growth. Events that agencies either know are going to attract significant public attention or that could attract attention if the agency focused the public’s attention on them, are chances to encourage users to turn to the agency to recieve reliable information as the events transpire.

Third, agencies should reply to user inquiries in a timely way whenever possible. A user sending a tweet to the agency is the online equivalent of a citizen approaching an officer on the street and asking a question. Each tweet sent by a user is a chance for the agency to engage and have a conversation.

Fourth, agencies should consider self-initiating conversations with Twitter users. Agencies should watch for tweets to which they can legitimately respond spontaneously and, in so doing, attempt to engage the user in conversation on a topic of mutual concern.

Conclusion

The Final Report of the President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing identifies “Technology and Social Media” as one of the six primary areas of focus, concluding that agencies should use social media “as a means of community interaction and relationship building” and that its use “must be responsive and current.”9 For police executives struggling with how—or even if—to staff a social media manager position, the research presented here may provide the first police-specific quantifiable data that could be used to help them make those decisions. Dedicating time and resources to employing a two-way engagement strategy will result in increased numbers of followers who will then receive critical public safety messages directly from the agency in as timely a manner as possible.♦

Lieutenant Zach Perron is the public affairs manager for the Palo Alto Police Department in California. He is the general vice chair of the Public Information Officers Section of the International Association of Chiefs of Police. He was a 2014 visiting fellow at IACP in Alexandria, Virginia, where he worked on national-level initiatives in their Center for Social Media. Lieutenant Perron is a graduate of Stanford University (BA, American Studies, 1997) and the Naval Postgraduate School (MA, Security Studies – Homeland Security and Defense, 2016).

Notes:

1President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing, Final Report of the President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, 2015).

2Zachary P. Perron, “Becoming More Than a Digital Bullhorn: Two-Way Engagement on Twitter for Law Enforcement” (master’s thesis, Naval Postgraduate School, 2016), 151.

3Ibid., 99.

4Ibid., 102.

5Ibid., 107.

6Ibid., 112–113.

7Ibid., 116.

8Ibid., 141–143.

9President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing, Final Report, 37.