The ongoing violence in U.S. cities in the aftermath of several notorious police shootings has resulted in the most serious nadir in community-police relations since the civil unrest surrounding the war in Vietnam in the late 1960s. The discussion about alleged police excesses and the need for significant reform has intruded itself into political campaigns and in many city and town councils where the “defund the police” movement is being embraced.

Police have been accused of being racist and biased, and it is claimed that inappropriate police behavior is not corrected because command fails to hold bad officers accountable. Further, notorious shootings, such as those of Amadou Diallo (New York City, 1999); Michael Brown (Ferguson, 2014); and Jacob Blake (Kenosha, Wisconsin, 2020), are cited to argue that police departments are either unwilling or incapable of changing.

Investigations of some of these shootings have concluded they were justified. Others have argued convincingly that the systemic racism purported to explain these excesses is a false narrative; that the seriousness of the crime and suspect behavior are key predictors to the use of force by police.1 Police leaders have defended their agencies and the profession in general with data confirming the high standards of the recruitment process, the extensive training of recruits at the academy on cultural diversity and other “sensitizing” factors, general orders that prohibit bias-based policing and require officers to intervene upon observing unprofessional behavior by their colleagues, the right of officers accused of improper behavior to be given due process during investigations, and so forth.2

While these arguments may be valid, they are also irrelevant in today’s hyper-critical climate, and this has led to a crisis. Riots are occurring, police budgets are being reduced, and critics are suggesting that police officers have lost their legitimacy as societal stewards. This is certainly a far cry from the heroism of first responders so publicly celebrated after the September 2001 terrorist attacks.

The effects of these public criticisms, condemnations, and budget reductions have been corrosive. Recruitment is increasingly difficult, and officers are retiring at the earliest possible date or just leaving the profession altogether. For those officers who remain, two negative manifestations are evident: the first, known as the Ferguson Effect, is that officers respond to calls for service but eschew proactive policing to avoid public criticism in an environment in which they feel their supervisors don’t have their backs. The second is the emergence of a cynical “us versus them” attitude. The effects of both developments are unfortunate because they stifle mutual interactions and conversations between the police and the communities they serve and reduce law enforcement services to many of the people who need them most. The result is to exacerbate the problems already discussed and further inflame the state of community-police affairs.

The Usual Solutions

Solutions such as community policing, resilience, implicit bias training for officers, encouraging community inputs, and mindfulness, along with the following recommendations are offered as mechanisms to improve community-police relations:

- Departments need to be attentive to their brand, and their brands must extol openness and shared communications that inspire mutual trust and respect.

- Officers need to see themselves as part of the community they serve.

- Officers must recognize they are problem-solvers and guardians, not just warriors and protectors.

- Community members are end-users of law enforcement services; they are not just obligations to be protected.

- It will take time to transform police culture.

- Officer wellness, while often overlooked, must be part of any improvement scheme.

The first four items above are obvious and need no further discussion here; however, the last two items dealing with cultural transformation and officer wellness bear further elaboration. As the author has argued elsewhere, there are significant impediments to effecting rapid organizational change.3 The key problem is that most law enforcement agencies are hierarchies, and therefore characterized by task specialization, the compartmentalization of information, inadvertent and purposeful information distortion due to different perspectives on information depending upon one’s location within the hierarchy, and the distance of the leaders from the lower levels (i.e., the streets) where action is taking place. The dilemma for chiefs and sheriffs is that hierarchical bureaucracies deal well with stable environments but not with dynamic ones in which change is required. In short, hierarchies resist change—just look how little the federal and state governments change, reforming promises of newly elected leaders notwithstanding. In fact, making rational decisions about changes in a dynamic environment is difficult, if not impossible. Cost-benefit calculations rely upon known acts and their consequences, but in a dynamic environment, acts and consequences, and therefore their costs and benefits, are difficult to predict. Decentralized structures are best suited to innovation, but they necessitate the leader allowing decision-making by officers closer to the action. However, giving up authority at the very time the chief or the sheriff is being excoriated for a department presumably out of control and amid expectations that he or she will rectify it is counterintuitive and unlikely. Finally, while heads of agencies are held accountable for all activities within their organizations, they often lack complete control to effect change. For instance, they may have problems getting rid of bad officers who are protected by a union.

This state of affairs is being discussed to disabuse law enforcement leaders that change will come quickly or easily. The challenge is to explain these obstacles to communities to mitigate their expectations of rapid change lest they accuse well-meaning law enforcement leaders of being unresponsive, incompetent, or unsympathetic. To date, nobody has discussed this obstacle with any candor in a joint community–law enforcement venue, and, as a result, expectations are disappointed, further compounding the problem.

The alleged shortcomings of officers have been the primary focus of police activities in past years, and this perspective has resulted in solutions such as better officer training, oversight, and discipline and accountability. Essentially, officers are viewed as the sources of the problem; therefore, control is seen as the answer. However, when one looks at the high rates of suicide, divorce, and alcoholism among officers, it becomes apparent that officers are also victims; the cumulative stresses of years of dealing with society’s problems and danger have deleterious effects upon officers. As one chief put it in the webinar, “Hurt people (i.e., officers) hurt people.” Officer wellness must be an integral component of any scheme to improve relations with the public.4 Ironically, funding for such programs is likely to be the first to disappear as police budgets are reduced. The answer to resolving some of these issues may come from a place of surprise to some municipal police leaders: college police.

Look to College Policing for Answers

College police officers often deal with identity crises. Students and faculty don’t recognize campus police as “real police,” despite the fact that they are required to demonstrate the same skills and exercise the same responsibilities as their municipal brothers and sisters. Sadly, municipal police are also part of the problem, thinking campus officers are not as professional since campuses tend to be safer than the surrounding communities, and, therefore, the job is not as dangerous. Clearly, this is not the case, as evidenced by active shooter incidents on campuses, among other high-risk incidents.5

Nevertheless, this inferiority complex does affect many campus officers who are eager to join municipal and county agencies. It is understandable that young officers leave for more exciting opportunities and broader professional development. The unfortunate outcome of this exodus is that it obscures the critical aspect of the community-police divide. Rather than college officers trying to become municipal officers, it is the municipal officers who should be seeking to emulate college officers because the latter have the secret to positive community-police relations!

There is a difference between municipal and college police, but it is a difference in the focus, not in the kind of work. As a municipal officer, one’s responsibilities may entail 80 percent protecting and 20 percent serving community members. As a college officer, the percentages are reversed—80 percent service and 20 percent protection. Everyday college policing does (or, at a minimum, should do) the very things that generate positive relations with their communities.

1. Empower the Community. Community policing has been quite popular for the last 30 years and is especially cited today as one of the keys to improving understanding and mutual respect between officers and the communities they serve. After all these years and tens of millions of dollars dedicated by departments to this activity, problems still exist if the current condemnations seen daily in the media are any indication. There are at least two reasons for the shortcomings in community policing. The first is that community policing is an action; it is not a result. Assigning outreach officers to a specific neighborhood and having them serve as liaisons to the department for local problems is essentially reactive. It relies on community members coming to their outreach officer to get problems addressed. This relationship keeps community members dependent on police for services and is at the heart of the problem with community policing. What college officers do is empower their communities, and empowerment is an outcome. Effective policing requires a partnership between communities and police, and law enforcement cannot be optimized without community involvement. This involvement includes more than just reporting suspicious activities to police. It also involves teaching community members to protect themselves as well as their campuses, homes, and families. Northern Virginia Community College (NOVA) Police assign a lieutenant and an officer who empower the campus community and host more than 20 presentations that teach people how to protect themselves in an active incident, apply a tourniquet, stay safe on the street (i.e., situational awareness), and reduce and de-escalate verbal conflict.6 Teaching people to exercise greater control over their own destinies is a powerful antidote to the perceived impotence that stokes their frustrations, especially in low-income neighborhoods. Further, these training sessions provide other positive outcomes: officers are seen as allies rather than enforcers of the law; community members who consider themselves to be allied with the police are more likely to actually say something when they see something; officers conducting the training are able to develop personal relations with attendees, again encouraging tips to police; community members are able to see the knowledge and professionalism of the officers, which enhances public perceptions of policing; and officers have opportunities to explain how and why police do what they do before a crisis occurs, thereby increasing community understanding.

2. Play on Their Turf. In most interactions with community members, such as traffic stops, police choose the location. However, college officers do presentations at various venues (i.e., their clients’ turf) throughout the campus community: convocations, classes, clubs, and faculty division meetings. As a result of these presentations, officers are often asked to address campus community members’ clubs, churches, and places of business. The key is active solicitation of opportunities to provide training. The police department can’t afford to sit back and await invitations; campus police work to generate them. The fact that campus officers are willing to go to their clients shows their desire to serve, which benefits the organization’s “brand” as a caring department.

3. Demonstrate Sensitivity. Universities often have very diverse populations—NOVA has students from 185 different countries. When one adds to that the many differences in race, gender, religion, and other characteristics, it is obvious that learning to deal with diverse populations is crucial at NOVA and other college campuses. Further, the college environment is one of experimentation, while officers, who are keepers of laws and rules, may be considered by many to be conservative and, therefore, not supportive of students testing boundaries. However, the previously suggested techniques also mitigate this problem. Training officers in conflict avoidance and de-escalation (e.g., verbal judo), cultural diversity, implicit bias, the potential for misunderstandings due to different interpretations of nonverbal cues, and mental health awareness (e.g., Crisis Intervention Team training) can further support positive relations with communities.

4. Provide opportunities for community inputs. The frequent presentations and opportunities for community-police interactions in non-enforcement activities offer multiple chances to explain police operations, answer community members’ questions, and respond to their concerns. One of NOVA Police’s most effective means of providing an explanation of operations and opportunities for communities to express their questions and concerns Safe Passage Home, a two-hour program where officers, working with role players, demonstrate the “what, why, and how” of both compliant and less-compliant traffic stops. The demonstrations are followed by a Q&A session where NOVA police personnel answer questions about traffic enforcement and any other items of interest to the audience and by soda and pizza—so community members can meet officers in a non-enforcement environment.

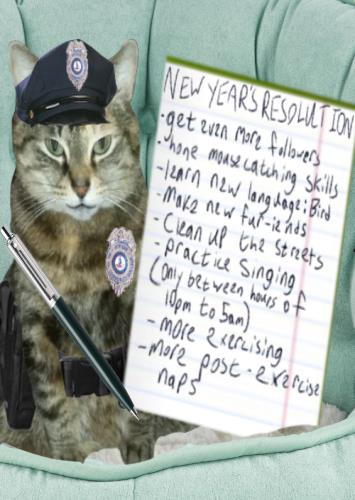

5. Promote transparency. This is the information age, and people want to be informed. Many departments are already using various mass media platforms to accomplish this goal. However, people generally will not pursue information unless it addresses an immediate concern. The trick is to make people want to consume the information. One of the more successful things NOVA has done is creating a virtual mascot: Penelope the NOVA Police Cat. Students love animals, and they have embraced the Penelope persona (catsona?). Her monthly safety tip in the department’s Public Safety Newsletter (nvcc.edu/police/psnewsletters.html) tripled readership, and her briefings (in which photos of Penelope are discussed by her minions) are always popular.7 Penelope also presents a fun and more human side of campus police. In addition, Coffee with the Chief, station open houses, foot and bicycle patrols, ride-alongs, and other engagement activities are all opportunities to inform the public of what the campus police do and the problems police face, to solicit community views, and to present an open image to the public.

Recommendations

Some of the foregoing examples from NOVA can be adopted by municipal agencies. The following are several other things agencies can do to increase positive effects within their communities.

First, remind officers that the most important part of dealing with the public is to listen to what a person is saying. While one may think everyone knows how to listen, that’s not true. As Stephen Covey wrote in Seven Habits of Highly Successful People, most people do not listen with an intent to understand; they listen with an intent to reply.8 For officers who have been on the job for years, there’s a tendency to assume a particular call is just like the hundreds of calls already worked, but this mindset robs an officer of an opportunity to learn the actual issues of a call and to demonstrate personal courtesy and a true desire to help.

Second, municipal police departments can approach local college police departments. Offer to partner with them in their campus activities and invite them to participate in municipal activities. This is a win-win strategy: campus officers get some help and meet local fellow officers while municipal officers can learn about campus officers’ empowerment programs and resources, interact with citizens in non-enforcement circumstances, learn to interact with a broader group of diverse individuals, and get some assistance in the municipal departments’ own community activities as well. Both agencies can profit from formal and informal information exchanges during these activities since campus members live or spend time in the surrounding community and locals from the community come onto campuses. Information exchanges can help both agencies keep both the campus and the surrounding community safe.

Third, agencies should work to refocus police academies. There has been much attention to providing enhanced training to officers on cultural diversity, implicit bias, conflict de-escalation, mental health issue awareness, and so forth. This is good, but there is much more the academy can do. Why not have academies host periodic presentations to the public about police operations? This openness and transparency will do much to show how and why officers do what they do. Furthermore, this will occur in a non-crisis environment. Too often, police explanations are made only after bad things happen and, while the explanations may be objective and legitimate, they are often interpreted as defensive rationalizations meant to protect the department rather than inform the community.

A Final Note

This article has advocated community empowerment and explored ways to achieve a mutually respectful and productive partnership between officers and their communities. This strategy works at NOVA and other college departments. At NOVA, for instance, the college police are held in high esteem by the campus community and the police-campus partnership is responsible for a 65 percent drop in reported crime in the last five years. This strategy of empowerment and relationship building can work in municipal agencies as well. d

Notes:

1For instance, see Heather MacDonald, The War on Cops: How the New Attack on Law and Order Makes Everyone Less Safe (New York, NY: Encounter Books), 2016; Heather MacDonald, “The Myth of Systemic Police Racism,” Wall Street Journal, June 2, 2020.

2These topics constitute up to 10 percent of training content at Northern Virginia police academies.

3See John M. Weinstein, “The Challenge of Innovation in Law Enforcement Organizations,” Police Chief Online, January 29, 2020.

4John Weinstein, “360 Degrees of Self-Survival,” The Police Chief 84 (May 2017): 26–29.

5This perception of campus policing is false considering active shooters on campus or in dorms or people from outside coming onto campuses to commit crime; plus, campus officers have special responsibilities and challenges (campus diversity) not shared by many municipal officers.

6All presentations are available upon request to the author.

7In fact, Penelope the Police Cat has become so popular that she has her own Instagram page with more than 1,300 followers from more than 60 countries: @penelopenovapolicecat.

8Steven Covey, Seven Habits of Highly Successful People (New York, NY: Free Press, 1989).

Please cite as

John M. Weinstein, “Building Understanding and Trust: Recommendations to Improve Community-Police Interactions,” Police Chief Online, April 20, 2022.