How often do people trust what they see on the internet? A popular internet pastime is looking for holes or issues with AI-generated images. For example, while faces in the foreground might look convincing, text, faces, and even hands in the background often have unrealistic aspects. In the ever-changing digital environment, relying on images and video helps people navigate the world.

The same thing holds true when investigating a crime. When a witness is interviewed to give a record of events, what steps do officers take to validate that testimony? When a crime is committed, and a weapon is found or used, what are the standard operating procedures for retrieving and keeping that evidence preserved? When a video or image is submitted as evidence, what steps are taken to ensure the information is accurate and unaltered?

At many agencies, there are almost certainly processes in place to investigate and preserve the integrity of the first two types of evidence, but likely fewer precautions for the third. Yet, as discussed previously in an article for this publication, entitled “How Understanding Video Evidence Is Vital for Your Organization,” the presence of image and video evidence as primary evidence continues to grow exponentially.1 As this evidence grows in volume, its ubiquity makes direct acquisition a massive drain on agency resources. This inevitably results in pictures and videos being submitted by witnesses, victims, or citizens who recaptured them from online sources.

The rise in computer-based tools, such as generative AI tools found in many popular programs (e.g., Midjourney, Dall-E, Adobe Firefly, and Sora AI), have given the average person tools with which to create complex fake media within moments. In speaking with the U.S. Senate Subcommittee on Consumer Protection, Product Safety and Data Security, Sam Gregory (executive director for the nonprofit human rights group WITNESS) stated,

Significant evolutions in volume, ease of access, personalization and malicious usage of generative AI reflect both the potential for creativity but also the heightened harms from audiovisual generative AI and deepfakes–including the plausible deniability that these tools enable, undermining consumers’ trust in the information ecosystem.2

As such, assessing and validating the media they receive are becoming vital steps in police investigations.

Submitted Media and Potential Pitfalls

In the last five years, there has been a growth in the number of options for images and videos to be submitted to agencies directly from the public. This has been an enormous help, as it allows officers to more quickly review the evidence and send out pertinent information to the public. This also frees resources for the agency, as an officer or video examiner no longer needs to go “into the field” to acquire a file that a witness or victim can easily remotely transfer. Depending on the length of the file, this can save hours at the scene, allowing officers to be back on the streets and reducing the work backlog for examiners.

The challenges occur when questions of originality, authenticity, and file integrity are raised. Additionally, the submitter may be needed to testify to the file’s origin, which is difficult in circumstances when the submitter is sending a file on the condition of anonymity. As has been seen in multiple examples, a file can be changed—with or without deceptive intent—but these changes may affect the admissibility of a file.

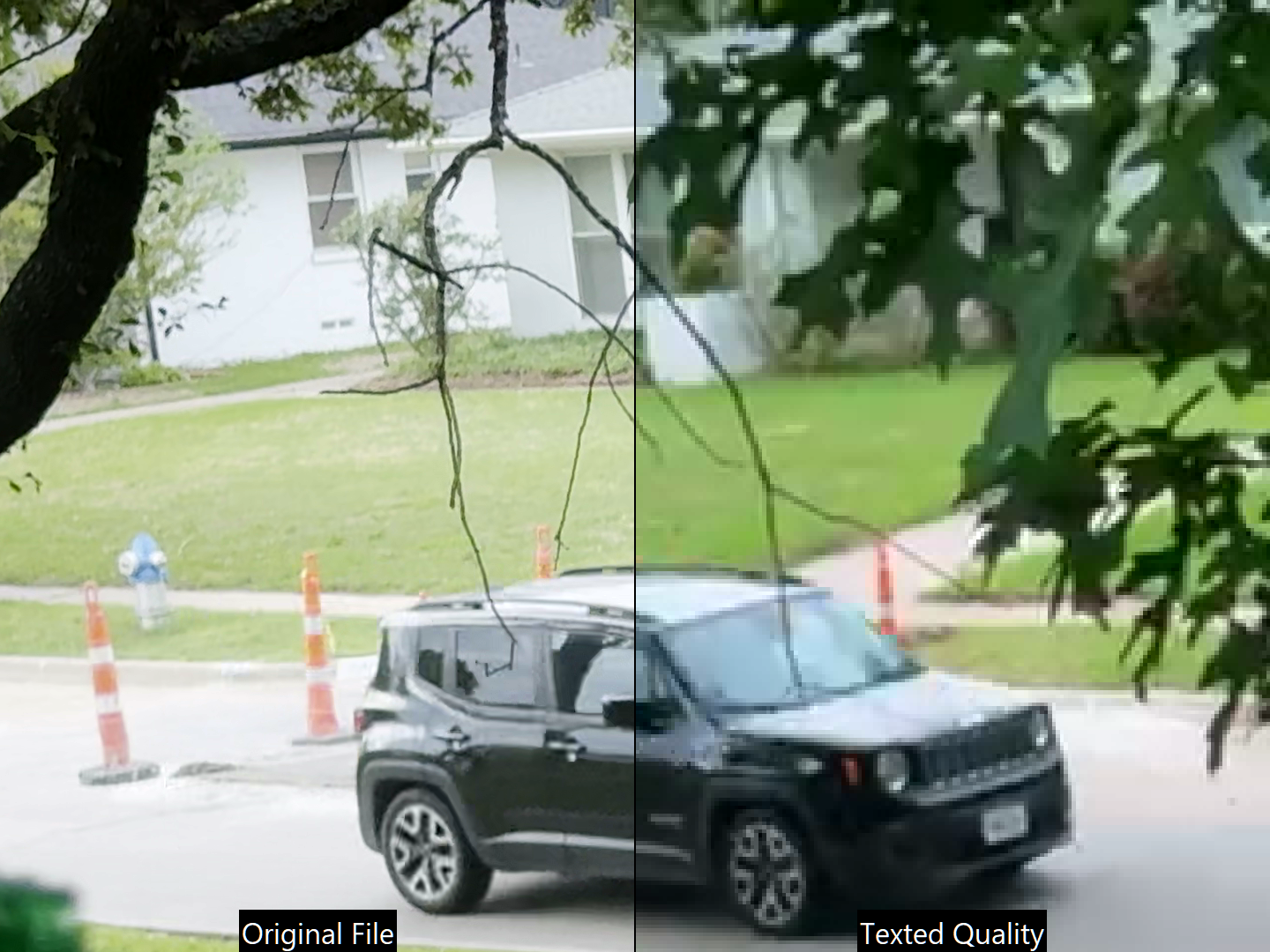

In a recent example, a video file was submitted to the prosecuting attorney’s office days before the trial was to start. The attorney received the file via Airdrop but then sent it via text message to the defense. As a result, an original file was not saved, and both parties worked with different qualities of evidence without even knowing it until the case was in deliberation. This simple process may have affected the course of the trial if not remedied (see Image 1).

What Does Authentication Mean?

When discussing image and video authentication, there are generally different terms that get merged together. For example, when a court asks if a video is authentic, it could mean, “Is the video the same as when it was submitted?”; “Is the video a clear and accurate depiction of what it purports?”; or “Are there signs of tampering or manipulation?” When looking at a digital image or video as evidence, separating and addressing each question individually becomes vital. In Amped Software’s Authenticate training, these questions are grouped into the categories of source identification, context analysis, integrity verification, and processing and tampering analysis.

Source Identification

When a file is either acquired or submitted as evidence, one of the first questions to be answered is, “Where did this file come from?” Source identification assesses to what level an examiner can validate where an image or video originated. These can mean answering questions like “What type of device recorded this?”; “What was the make and model of the camera that recorded this?”; “What specific device was this recorded on?”; and even, “Was this file saved from or sent across the internet?”

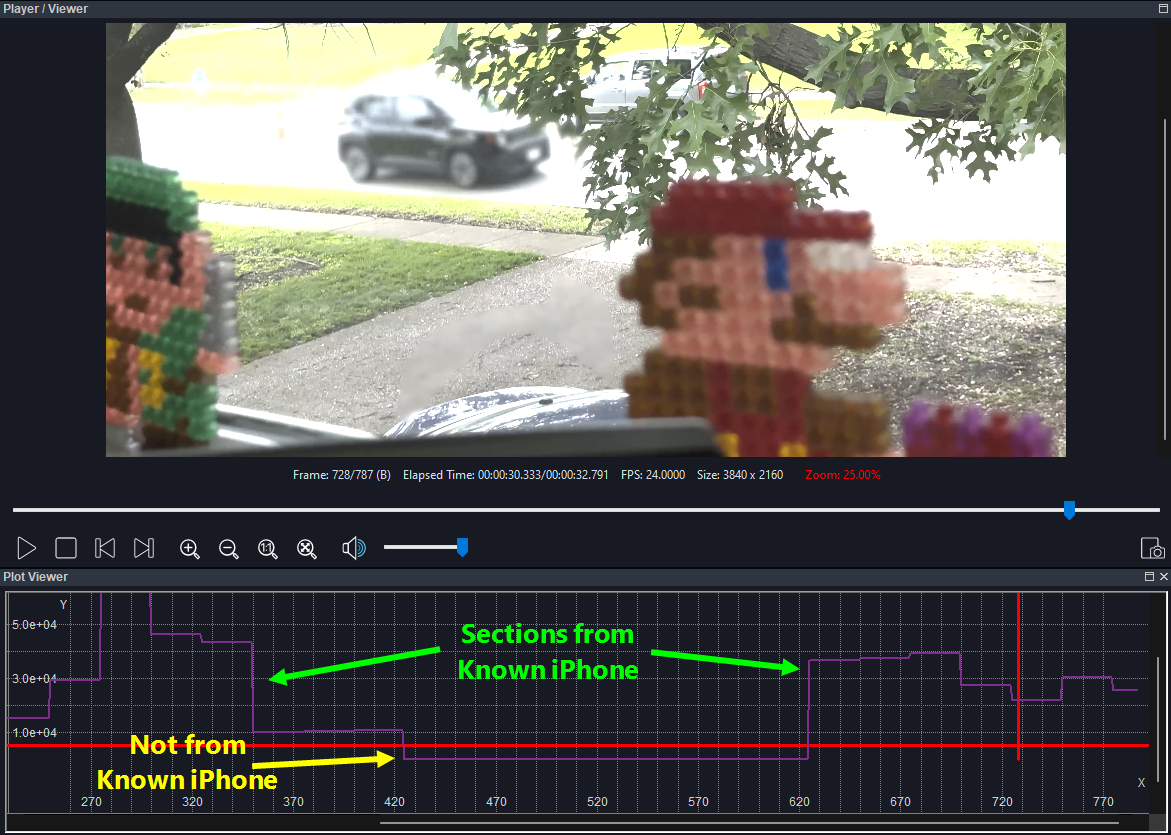

For example, Image 2 was taken with an iPhone 15 Pro Max. In the source identification process, this information would answer two of the questions. By digging deeper into the file, it can perhaps be tied to a specific iPhone, which can clarify whether the device that submitted it recorded the image or received it from another source. If the file was sent to the device, investigators would want to know more about how it was sent (e.g., via a cloud service, from a text message, saved from social media). Clues can also be looked for to determine if the file was opened, edited, or saved using a software application.

Context Analysis

Another common request is whether the media is a fair and accurate depiction of what it claims to be. A vital part of answering this question involves context analysis, which addresses what is in a photo or video and the circumstances around the image. Often, this will look at the context of the scene, the time and geographical context, and the process for creating digital files and publishing.

This category is helpful because it helps address images where scenes from a protest are re-used from previous events, where the time and dates within the image do not match the time and dates of the incident, or where the events were staged as a reenactment. One recent example came as part of an alibi in a homicide case. The suspect in this case had submitted a video from social media that placed the suspect in another state at the time of the murder. In the context surrounding this video, the dates and time showed a recently recorded video, and no data matched or placed the video in that state.

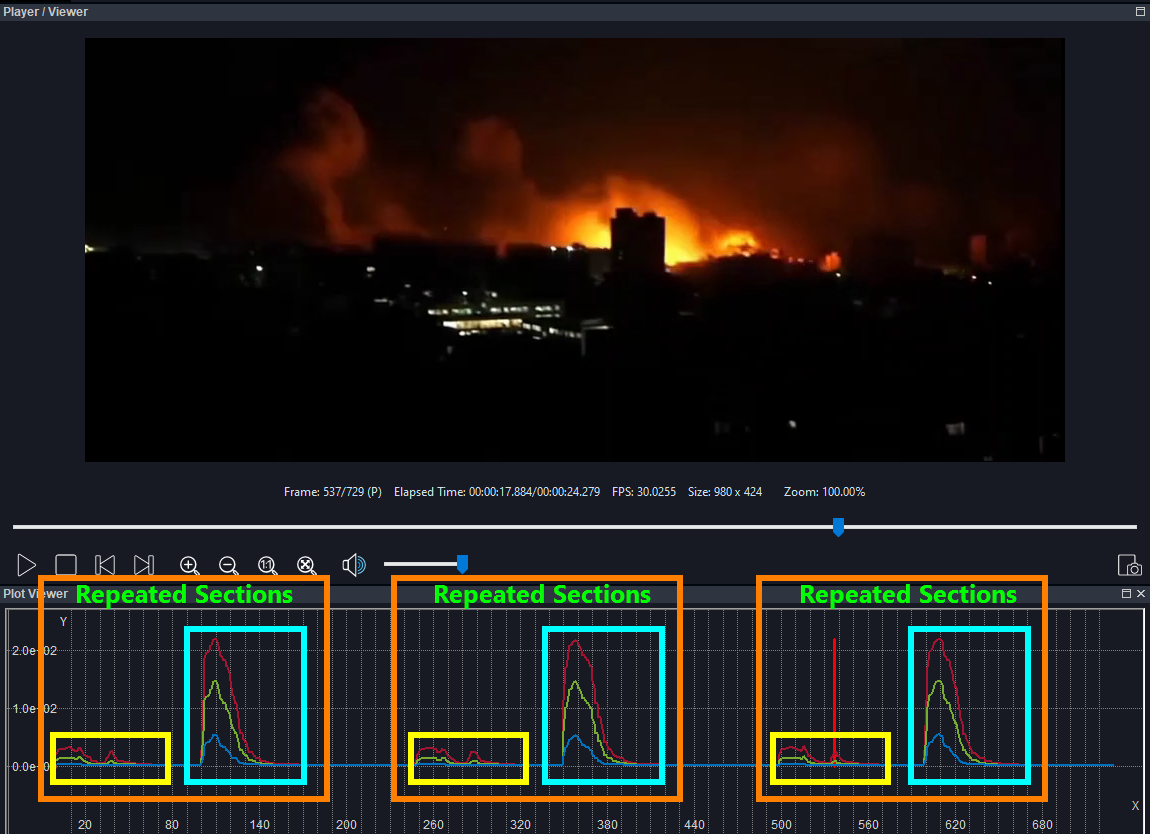

Another example where context is in question would be a video posted to social media. A further examination would be needed to make sure whether the entirety of the video was submitted or it was trimmed before being posted. Trimming videos can be done for several reasons, including innocent ones, such as a social media platform only allowing a maximum length for the video or cropping the image to fit into a square. In Image 3, the footage from a bombing posted to a news channel’s feed shows the same explosions repeated three times so that the video filled the preset timing of a video clip and, perhaps, to make the event appear more dramatic.

Integrity Verification

Every department should have precautions to ensure that image or digital files are unaltered from the time of acquisition. Steps that are commonly used for digital files include documentation of the chain of custody, writing a file to a storage medium that cannot be altered (e.g., DVD-R and Blu-ray-R), and generating a digital fingerprint for the file (a process known as “hashing”).

But what happened to the file before it was given to the department? Integrity verification is the process of looking at other files that follow the same source generation as well as clues left in the structure or metadata to identify whether inconsistencies may exist. This can be done by looking at how most files on a device are created and seeing if there are inconsistencies in the evidence item. For example, if many images are saved on a phone in a .jpg format, but the one submitted from the incident is saved in a .png format, then this may mean the image didn’t come from the device or was resaved at a later time. In a recent test, a video saved in one format (h.265) on the phone was changed to an entirely different format with more compression (h.264) just by being sent through a cloud portal.

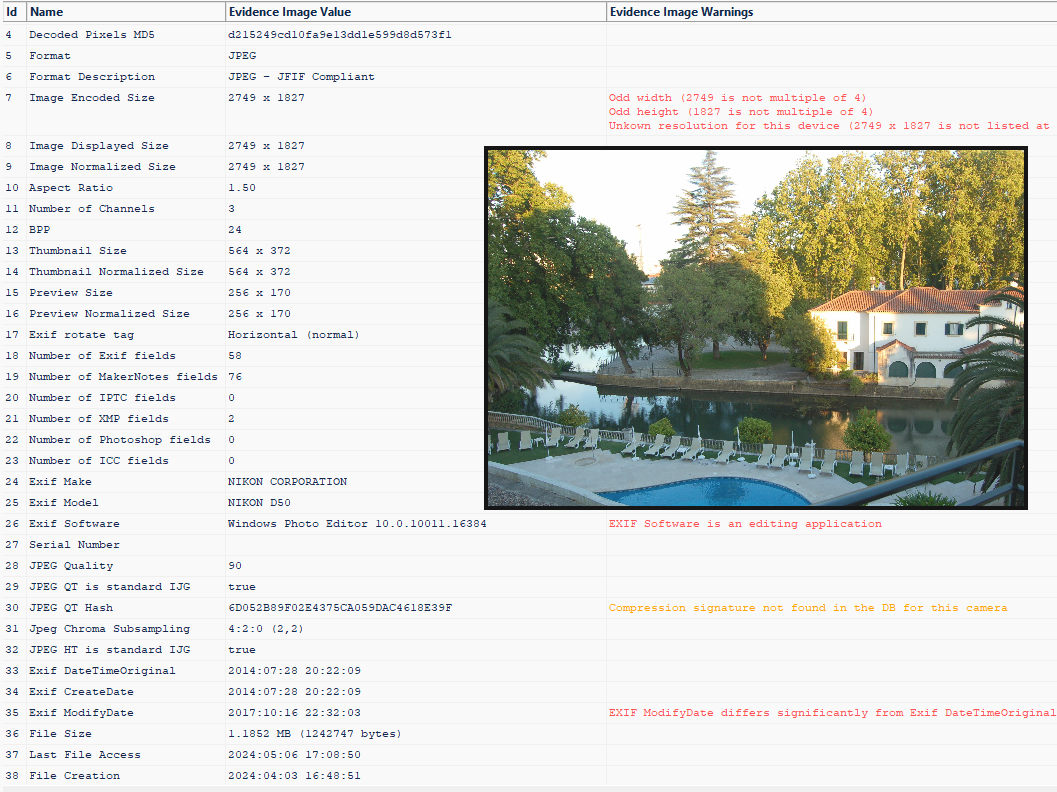

When a file cannot be compared to others from the same device, additional clues can be sought based on the standard image generation model. The image below appears to be consistent with the expected output of the camera that took it, according to several free public tools. However, looking at it compared to a common generation model (see Image 4) shows several inconsistencies that might mean this was edited, cropped, or resaved before it was submitted.

Processing and Tampering Analysis

While tampering is the most commonly thought of when discussing image and video authentication, it is often not the first one investigated. While a visual analysis can frequently show obvious attempts at tampering (for example, an edge that doesn’t match in a swapped face), as technology improves, the human eye alone may be unable to detect the changes.

Images have been subject to tampering and processing almost since cameras existed. In her article ”Deepfakes in the Dock: Preparing International Justice for Generative AI,” international criminal lawyer Raquel Vazquez Llorente reports that “spirit photography” has been documented as far back as 1869.3 Since the early days of silent theater, special effects teams have been stretching what is possible for creative uses in movies and films. And, much like today, tools and experts have been needed to “prove” what is real and where there are signs of manipulation.

Generally, the processes used in tampering with a photo range from cropping an image or video to adding or removing details or even replacing subjects’ faces in an image or video. As technology advances, new tools and methods are needed to identify signs of tampering. Examples of these techniques include looking for signs of double compression, cloned or duplicated areas, and even geometric inconsistencies (such as shadows). These processes, which differ mathematically based on the file type, can help find unreliable regions in both images and videos.

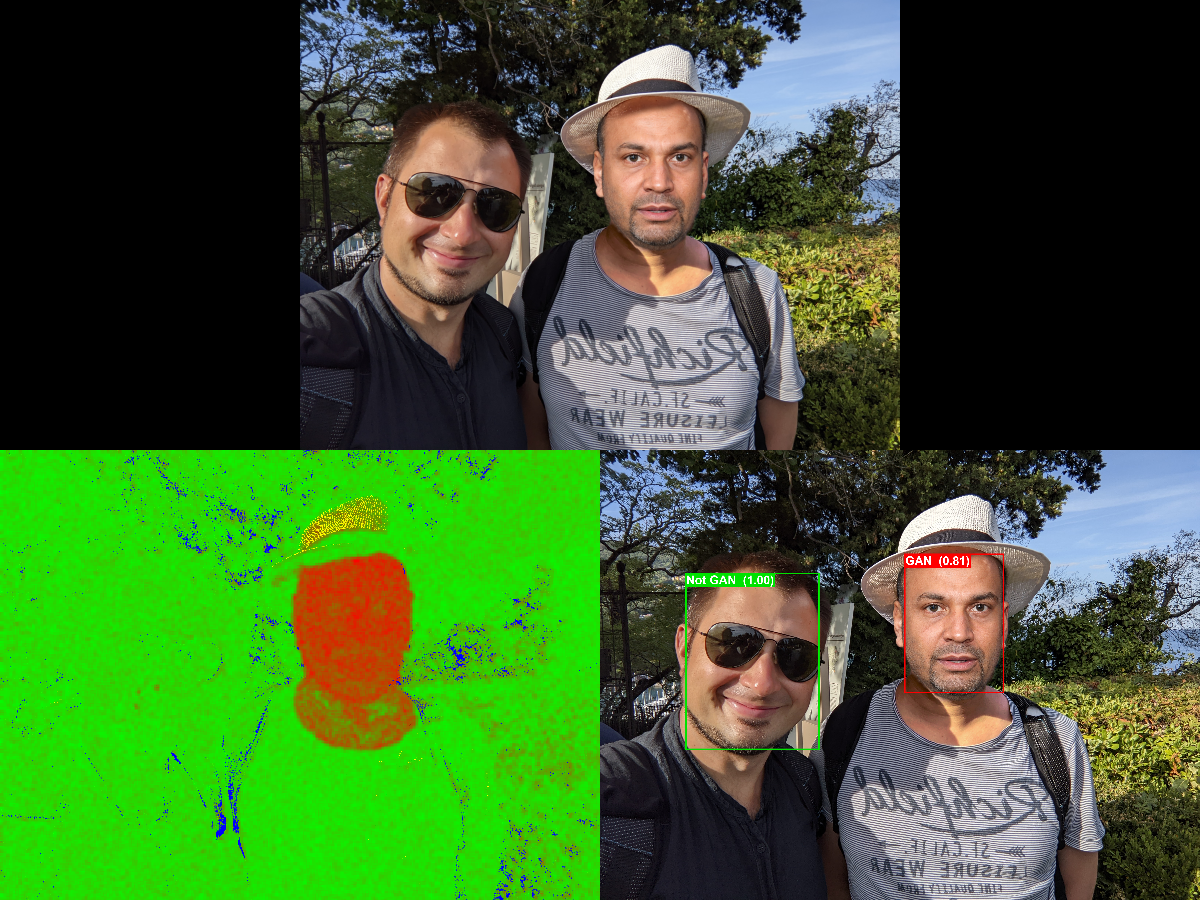

As generative tools become more prevalent, new tools and techniques are needed to address them. Research shows that current AI models struggle with generating consistent shadows from a single source. Tools can also be created, such as the Face GAN Deepfake filter, the Shadows filter, and the new Diffusion Model Deepfake filter, to aid examiners in determining if what they are seeing is a camera original or something that was artificially created. These techniques must be reliable for present models but able to adapt as technology changes. This is why no single filter will find every sign of tampering, and also why Amped Authenticate employs several filters.

In Image 5, multiple filters are used to show that the face on the right was added later, and that it was created using a Deepfake method known as a GAN (Generative Adversarial Network).

Resources and Best Practices

These processes are vital to adding credibility to media that agencies receive or do not acquire directly from a source near the time of the incident. To agencies that are just beginning this process, it can be overwhelming. Thankfully, several resources are available to aid in image and video authentication. The Scientific Working Group on Digital Evidence (SWGDE) has best practices for both image and video authentication. Companies such as Adobe, Microsoft, and Google utilize a watermarking application called C2PA to help document when generative AI tools are employed. Lastly, Amped Software builds on both of these suggestions with an application called Amped Authenticate, which uses multiple filters and processes to examine images and videos for all four authentication aspects.

So, while bad actors have tried to obscure their actions in media files for many years, having the proper understanding, the right tools, and a healthy skepticism will help validate the information an agency receives in submitted media. The old saying “You can’t believe everything you see on TV” has now become “You can’t believe everything you are sent as evidence.”

| Amped Software develops solutions for the forensic analysis, authentication and enhancement of images and videos to assist an entire agency with investigations, helping from the crime scene, up to the forensic lab, and into the courtroom. Amped Software’s solutions are used by forensic labs, law enforcement, intelligence, military, security, and government agencies in more than 100 countries worldwide. With an emphasis on the transparency of the methodologies used, Amped Software’s solutions empower customers with the three main principles of the scientific method: accuracy, repeatability, and reproducibility. For more information, visit ampedsoftware.com. |

Notes:

1Blake Sawyer, “How Understanding Video Evidence Is Vital for Your Organization,” Police Chief Online, August 16, 2023.

2The Need for Transparency in Artificial Intelligence, Testimony Before the U.S. Senate Committee on Commerce, Science and Transportation, Subcommittee on Consumer Protection, Product Safety and Data Security, 118th Cong. (2013) (Sam Gregory, Executive Director, WITNESS).

3Raquel Vazquez Llorente, “Deepfakes in the Dock: Preparing International Justice for Generative AI ,” The SciTech Lawyer 20, no. 2 (Winter 2024): 28–33.