In a June 2021 Special Session, the Connecticut House of Representatives voted to become the 19th state to legalize the use of recreational cannabis for adults over the age of 21. The state capitol, still reeling from COVID restrictions, remained partially closed to lobbyists and the public. Legislators, largely confined to their offices, did not have the benefit of engaging with advocates on both sides to sway their decisions, nor was there a lot of input shaping the final bill. This led to deficiencies that didn’t rear their head until years later. As of February 2025, 24 U.S. states—Alaska, Arizona, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Illinois, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Montana, Nevada, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, Rhode Island, Ohio, Oregon, Vermont, Virginia, and Washington—as well as Washington, DC; Guam; and the Northern Mariana Islands, permit recreational marijuana use.1

“As drugs become more mainstream and technology advances, states should reexamine guidelines to conduct advanced toxicology testing to increase their knowledge and be prepared to respond. For the first time since 2017, no additional U.S. states legalized cannabis for adult use; efforts in Florida, North Dakota, and South Dakota were all defeated.”

Cannabis continues to be on the ballot. In November 2024, voters in North Dakota, South Dakota, and Florida considered state constitutional amendments that would allow for the possession, purchase, and use of marijuana for nonmedical purposes by adults 21 and older. For years, conversations touting the benefits of marijuana have minimized the risks, garnering support for legalization from many, but not all. Concerns about impaired driving have started to gain ground in the conversations, especially as traffic crashes, roadway fatalities, and wrong-way drivers continue to rise across the United States. The legalization of recreational cannabis failed in Florida largely for this reason. The Florida Department of Transportation produced a campaign advertisement about the dangers of driving while high. “DUI crashes increase in states with legalized marijuana, putting everyone at risk,” the narrator in the ad said.2 “In states where marijuana has been legalized, there is a troubling rise in fatalities linked to marijuana-impaired driving,” said the governor’s wife, Casey DeSantis, during a press conference in November 2024. She said deaths from driving under the influence of marijuana increased 22 percent in Oregon and 14 percent in California.3 Maybe the tides are turning. For the first time since 2017, no additional U.S. states legalized cannabis for adult use; efforts in Florida, North Dakota, and South Dakota were all defeated. Only one state (Nebraska) will adopt a medical program this year, bringing the total for legalized medicinal cannabis up to 39 states.

It’s Legal—Now What?

It depends on the state. One would think that open container laws for cannabis would mirror those of alcohol to prevent consumption while driving and ensure that cannabis products are secured, packaging remains unopened, and out of reach in the main passenger compartment of vehicles.4 But not in Connecticut! Contrary to that thinking, Public Act 21-1, Section 18, limits when cannabis odor or possession can justify a search or motor vehicle stop by law enforcement. The law generally provides that the following do not constitute (in whole or part) probable cause or reasonable suspicion and must not be used as a basis to support any stop or search of a person or motor vehicle:

- The possession or suspected possession of up to five ounces of cannabis plant material (or an equivalent amount of products or combined amount);

- he presence of $500 or less in cash or currency near the cannabis; or

- The odor of cannabis or burned cannabis.

Though the legislation allows law enforcement officers to conduct a test for impairment based on this odor if the officer reasonably suspects the operator or passenger is violating the DUI laws, any evidence discovered through a stop or search that violates these provisions is not admissible in evidence in any trial, hearing, or other court proceeding. In a nutshell, it is illegal to drive impaired in Connecticut; however, the police are prohibited from stopping an individual very obviously and visibly smoking cannabis while driving (absent other probable cause).

The Connecticut Department of Transportation (CTDOT), Office of Highway Safety reports:

In Connecticut, the incidence of wrong way crashes and fatalities has risen to an alarming number, and at an alarming rate. There were more wrong-way crashes and fatalities in 2022 than the previous three years combined. In 2024, there have been as many wrong-way fatalities in the first three months as there were in all of 2023. And most are attributed to alcohol or drug impairment.5

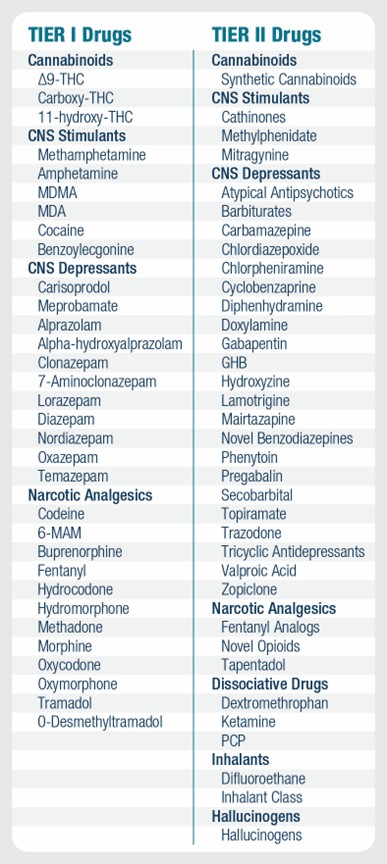

Coincidence? It seems to be a U.S.-wide trend. According to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, one person was killed every 39 minutes in an alcohol-related crash in 2021.6 But alcohol is not the only concern; the use of illicit drugs, legalized drugs such as cannabis, and prescription medications may also impair a driver’s abilities. According to a 2022 estimate, approximately 13.6 million people drove under the influence of illicit drugs in 2021.7 The National Safety Council has recommended that forensic toxicology labs regularly test blood for 35 of the most often encountered drugs and metabolites. Referred to as Tier I drugs (see Figure 1), they are now included as a testing standard in many forensic toxicology labs. Tier II drugs include emerging novel psychoactive substances, prescription drugs, and traditional drugs of abuse with limited or regional prevalence, many of which require advanced instrumentation for detection.8

Problems with Enforcement

According to the American Bar Association, the current available methods of testing drivers for or detecting THC, the active ingredient in cannabis, or any other impairing substance, include urine, breath, oral fluids, and blood test. All of these methods face unique challenges.

Urine— The collection cannot be accomplished roadside; must be monitored to preserve integrity, but cannot be forced; and implies some indignity for both the observer and the subject. THC in urine, though, likely represents a metabolite of THC that fails to demonstrate a level of impairment at the time of vehicle operation.

Breath— This method provides the shortest detection window for THC, and if a breath quantification for THC impairment existed, as it does for alcohol, detecting THC impairment could be relatively simple. To date, no such measure exists.

Oral fluid— This test also has a short detection window, is a relatively quick process, can be completed roadside, and is not invasive.

Two states—Alabama and Indiana—have permanent or active oral fluid roadside screening programs. Michigan allows the collection of oral fluid only for the state’s pilot program. Minnesota began its pilot program in October 2023.9

Indiana’s Criminal and Justice Institute’s (CJI) Roadside Oral Fluid Program was created as part of the Great Lakes, High Stakes project, to address the emergence of drug-impaired driving on Indiana roads. Through the agency’s Traffic Safety Division, CJI is equipping law enforcement officers with a handheld analyzer that uses an oral fluid swab to detect the presence of six kinds of drugs: cocaine, methamphetamine, opiates, cannabis (THC), amphetamine, and benzodiazepines. It’s like a portable breathalyzer, but instead of testing for traces of alcohol, it detects the presence of drugs.10

Blood— Testing a driver’s blood is an invasive technique that may present Fourth Amendment concerns, requires special training and handling of the specimen, and requires a search warrant under most circumstances and in most states.

Law Enforcement Phlebotomy Programs (LEPP) tend to pose more challenges as the procedures need to be permissible by law. States have different views on who can administer, training protocols, and civil right issues.

Over time, case law developed, and the Arizona Court of Appeals ultimately affirmed Arizona Department of Public Safety’s interpretation of who was a “qualified person” to draw blood. In short, under Arizona law, “a person is ‘qualified’ to draw blood for DUI purposes if he or she is competent, by reason of training or experience, in that procedure.”11 Most states are modeling this “qualified person” statute in developing their LEPP.

- Arizona, Utah, Idaho, Minnesota, Maine, Washington State, Illinois, Georgia, Indiana, and Missouri have LEPPs. Mississippi and Montana have pilot programs, and Kentucky, Wisconsin, and Pennsylvania are starting LEPPs in 2024–2025.

- The Connecticut LEPP pilot program is offered through Hartford HealthCare and CTDOT. Officers must meet certain criteria to be considered for training, including being a full-time police officer and having experience with DUI laws. The training consists of 80 hours over two weeks, and officers must perform 100 vein punctures.12

Many states rely solely on drug recognition experts (DREs), officers who have received specialized training and been credentialed by the International Association of Chiefs of Police, to evaluate suspects and determine

- If the subject is impaired and

- If a medical condition is causing the impairment, or

- If a drug is causing impairment and if so which drug category(s).

There are more than 8,000 certified DREs in the United States, or approximately 1.1 percent of all law enforcement officers.13 This proportion falls short in handling increased drug legalizations and the unavoidable problems that come with it.

Stop Limit Testing

If a sample meets or exceeds a pre-determined blood alcohol concentration threshold, some labs will not perform any additional drug tests. This cutoff is most commonly either 0.08 percent or 0.10 percent.14 The proscribed per se blood alcohol level in the United States, across every state is 0.08 percent (except Utah, where it is 0.05 percent). Labs that adhere to this practice will not detect other drugs that may cause or contribute to driving impairment. This stop limit testing can interfere with a comprehensive understanding of drug involvement in impaired driving. Why do so many labs use it?

- Toxicology labs have limited budgets and resources.

- Driving impairment can be explained by the blood alcohol concentration alone.

- A lack of enhanced penalties for drug use means there is no need to measure beyond the blood alcohol level.

- Agencies that use the laboratories’ services have requested this limit.15

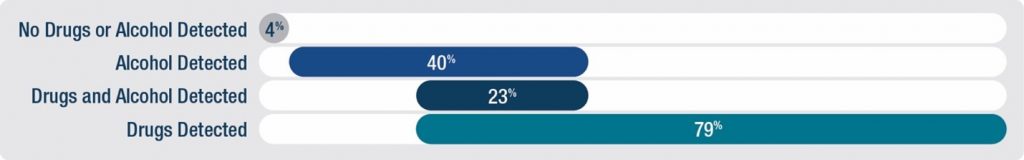

Researchers estimated the frequency with which drugs contribute to the national driving under the influence of drugs (DUID) problem by testing 2,514 cases using a scope of 850 therapeutic, abused, and emerging drugs. They examined deidentified blood samples randomly selected from a pool of suspected impaired driving cases. The samples were collected from NMS Labs in Horsham, Pennsylvania, between 2017 and 2020. Of the 2,514 suspected DUID cases examined:

- The overall drug positivity (Tier I or Tier II drugs) was 79 percent, nearly double the 40 percent positive for alcohol (see Figure 2).

- A smaller portion of cases (23 percent) tested positive for both drugs and alcohol.

- Only 17 percent of the cases were positive for alcohol alone.

- Naturally occurring cannabinoids experienced a statistically significant increase in positivity over the four years.

“Limiting testing based on alcohol results precludes information of drug involvement in several cases and leads to underreporting of drug contributions to impaired driving,” said Mandi Moore, one of the researchers involved in the study.16 As drugs become more mainstream and technology advances, states should reexamine guidelines to conduct advanced toxicology testing to increase their knowledge and be prepared to respond.

Problems for the Future

As law enforcement personnel grapple with the legalization of cannabis and the United States deals with an astronomical increase in drug overdose deaths, some states are adding more drugs to the mix. In 2020, Oregon became the first state to legalize psilocybin (psychedelic plants) products for persons aged 21 and older. Colorado was soon to follow. In 2024, Massachusetts, where medical and recreational marijuana is already legal, voters denied an attempt to legalize psychedelics. For several years, bill proposals were in front of the CT General Assembly. But the movement hasn’t garnered enough traction for legalization to cross the finish line.

Hope for the Future

Though it seems bleak, advances in technology will make it easier to test for impairment. To use new tools, most states need to adjust their laws to ensure law enforcement can administer drug tests. More parties are speaking up on the dangers of impaired driving, drug dependence and, roadway safety and demanding legislators make changes. Coming from ad campaigns from departments of transportation; education in the schools; and hopefully, the drug dispensaries—is one cohesive message: Don’t Drive High. As states enter the 2025 legislative session, one can predict distracted driving, the legalization or decriminalization of “magic mushrooms” (psilocybins), and roadway safety will top many agendas. Now is the time to make a plan for one’s state.

The goal is not to have the same rules; rather it is key to make sure the rules are working for the specific state. At a time, when people are screaming about roadway safety, they are looking to lawmakers and law enforcement to find a solution. They don’t have the answers, but the police and legislators do.

The Police’s Task

In a world of multiple problems over roadway safety, there are a lot of solutions. Police leaders should do their research and see what’s working in other states. State laws differ greatly. Review and know the laws of the applicable state. Advocate for policy change if there are techniques that need legislative approval. Develop a pilot program. Research grants. Analyze and track data. Ask questions—What needs to be done? Where are the legislative shortfalls? Law enforcement needs to dominate these conversations. Talk to legislators and be a part of the process. Most organizations have a lobbyist who can assist police leaders with the legislative process. Speak up. Be loud. The voices of those who protect communities need to be heard. d

Notes:

1National Council of State Legislatures (NCSL), “Drugged Driving | Marijuana-Impaired Driving,” Brief, updated March 27, 2024.

2Julia Rogers, “Research Backs Critics of Recreational Marijuana Saying It Will Increase Crashes, Traffic Deaths,” NPR, November 4, 2024.

3Rogers, “Research Backs Critics of Recreational Marijuana Saying It Will Increase Crashes, Traffic Deaths.”

4Responsibility, “Open Container Laws,” 2020.

5State of Connecticut, Office of Highway Safety, “Wrong-Way Driving,”

6National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA), “Risky Driving.” 7Select illicit drugs include marijuana, cocaine (including crack), heroin, hallucinogens, inhalants, or methamphetamine. For more information, see Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services, 2022 NSDUH Detailed Tables, Table 8.35A.

9National Conference of State Legislatures, “Drugged Driving | Marijuana-Impaired Driving.”

10Indiana Criminal Justice Institute, “Roadside Oral Fluid Program.”

11State ex rel. Pennartz v. Olcavage, 200 Ariz. 582, 588 (2001).

12NHTSA, Law Enforcement Phlebotomy Toolkit: A Guide to Assist Law Enforcement Agencies with Planning and Implementing a Phlebotomy Program (U.S. Department of Transportation, 2019).

12Connecticut Department of Transportation, “Law Enforcement Phlebotomist Pilot Program Training Application,” January 2025.

13Institute of Police Technology and Management, “Drug Recognition Expert (DRE) Program.”

14Amanda D’Orazio, Amada Mohr, and Barry Logan, Updates for Recommendations for Drug Testing in DUID & Traffic Fatality Investigation (The Center for Forensic Science Research & Education, 2020).

15Barry Logan, Assessment of the Contribution to Drug Impaired Driving from Emerging and Undertested Drugs (Center for Forensic Science Research and Education, 2023).

16Thea Clare Leavitt, Stanford Chihuri, and Guohua Li, “State Cannabis Laws and Cannabis Positivity Among Fatally Injured Drivers,” Injury Epidemiology 11, no. 1 (April 2024): 14.

Please cite as: Jill Barry, “Cannabis Contradictions and Challenges: Connecticut Case Study,” Police Chief Online, March 5, 2025.