Crisis Intervention Training (CIT) is a model law enforcement mental health collaboration program that is believed to benefit patrol personnel in their encounters with individuals experiencing a psychiatric crisis.1 Researchers have noted that CIT programs increase officers’ knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors, which, in turn, positively impact the outcomes for the call subjects, the officers’ organizations, and their communities.2 While the implementation of such CIT trainings vary in style, length, and content implementation and delivery, many law enforcement training instructors perceive that teaching the topic of mental health is one that may be met with some resistance by law enforcement officers despite research findings supporting its efficacy. When the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department (LASD) received county funding to create a hybrid program uniting sworn supervisors and department psychologists to teach a 32-hour curriculum to patrol deputies, the defined intent of the program was to provide basic training on de-escalation strategies and mental health symptoms or presentations frequently encountered during law enforcement contacts. Additionally, deputies would receive information about community supports and resources that could provide community members with tangible nonemergency choices that could be accessed prior to the escalation of a crisis and a desperate call for help to law enforcement personnel.

The LASD course structure, while adhering to the fundamental tenants of the CIT Model, aka the Memphis Model, also transcended this basic structure for its identified agency-specific needs and became operational in December 2016. The team of four instructors, consisting of two sergeants and two department clinical police psychologists, carefully addressed the question of “What can we do in our class to minimize oppositional attitudes or a negative mind-set from patrol personnel because of their frustrations with mental health–related calls?”

The class begins with activities to address the prospective oppositional concerns and, over the course of four days, creates a learning environment that empowers the deputies—in their skill sets and in their own self-awareness and learning—to rise to one of the greatest challenges facing law enforcement today. The LASD-CIT course increases in content depth and breadth over the course of the consecutive four days, scaffolding thematic integrated blocks of instruction that highlight clinical content, department policy, community partnerships and resources, and de-escalation strategies for utilization during calls for service involving persons with suspected mental illness.

While the instructional team also tracks anonymously reported, empirically based course evaluation data and deputy input to gauge students’ learning over the span of the entire course, the instructors noticed (anecdotally at first) that there was a notable and profound secondary effect: while deputies are engaging in this synergistic course experience, deputies themselves are also reporting insightful changes in their clinical understanding, their level of emotional responsiveness and empathy, and positive changes in their overall mind-set about the topic of mental health. The deputies openly reported not only that they would apply these concepts to the persons they protect and serve everyday but, more significantly, that they are further driven or feel empowered to utilize these course concepts in their own lives beyond the badge. Instructors noted that deputies described what researchers and management aspire to create—a personal and professional paradigm shift in the way that law enforcement officers think about mental health in their contacts with others and within themselves. These changes in their thinking and beliefs impact the very culture that the deputies create through their service to the department.

The LASD-CIT Course Content

On the first day of the course, students have the opportunity to discuss the stigma associated with mental health as perceived in the media, in the department, and in culture in general. This activity is an opportunity for deputies to emotionally “purge” and openly (but constructively through careful instructor facilitation) discuss some of the common frustrations deputies experience daily. This is a necessary cathartic step in identifying potential barriers to a deputy’s openness to new information and his or her potential integration or application of course materials and concepts in subsequent responses to calls for service. During this discourse, some students reported their resentment and discontent with their “volun-told” attendance in the course. Some students reported their dissatisfaction with the perception of their evolving role as law enforcement officers given the media coverage of lethal use-of-force police contacts and money spent on specialized services and units to address calls for service with defined or implied mental health presentations. Despite the negative elements discussed during the purge period, students have consistently disclosed that they have family members affected by mental health conditions (such as Autism, Alzheimer’s Disease, and Dementia) and that these conditions have significant impacts on their everyday lives—both personally and professionally. Once the students have the opportunity to voice their opinions and feel their concerns were authentically heard by the instructors (and that the students’ concerns will be alleviated with tools and resources provided in the course), they are more prepared to be receptive to subsequent information.

In a parallel process, on a microcosmic level, the instructors observed over time that the intensity, disdain, and duration of the purging conversation among students declined with each successive class. The instructors noted that this decline was consistent as was the steady increase in anecdotal positive comments that students reported from their fellow deputies and station-level training coordinators about the class—students had heard from their peers that the class was “one of the best trainings the department puts on” and “lots of useful info” (as they shared on their course evaluations and the training coordinators have shared via email) and were therefore open to the class experience. It appeared that, with the positive feedback from former students and training coordinators, the stations with large numbers of attendees would produce future classes with large numbers of attendees.

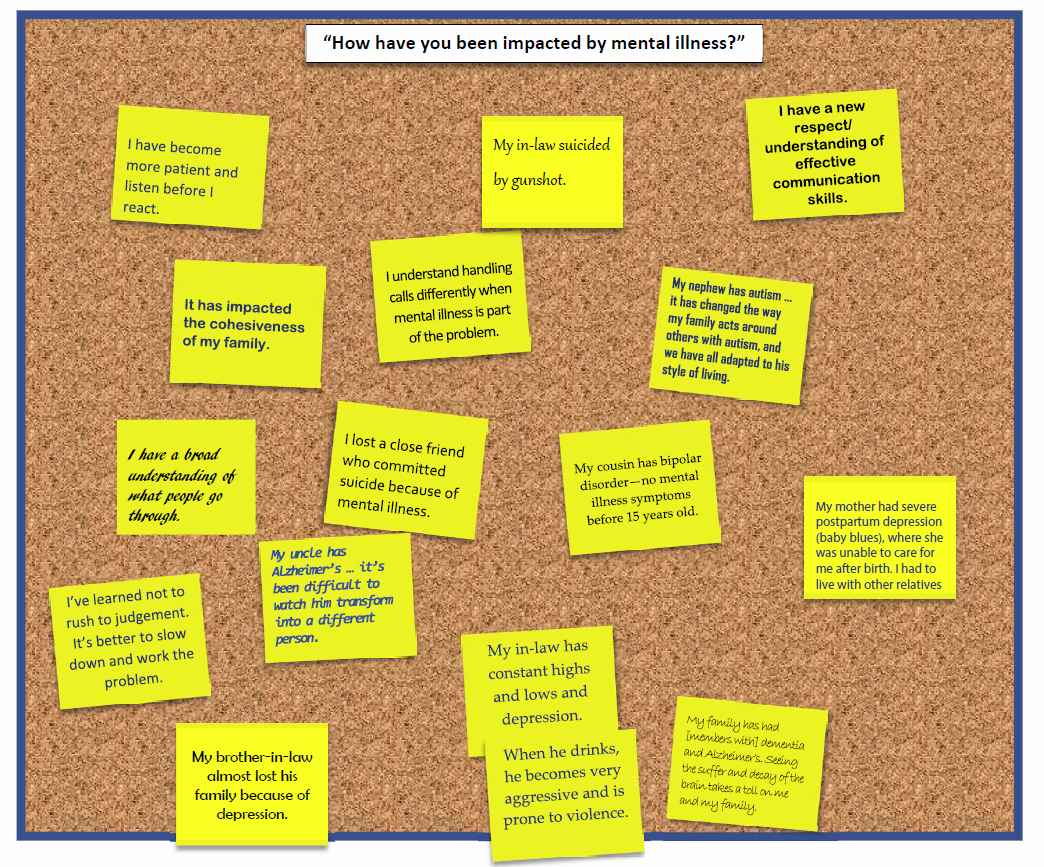

At the end of the first day of instruction—with curriculum blocks addressing mental health stigma, the “emotional purge,” mental health definitions and history of treatment, mental health diagnostic symptoms or behavioral features, and difficulties balancing departmental expectations (policy vs. station application) due to the increased frequency and duration of deputy calls relating to mental health—the deputies are asked to participate in a self-reflective learning activity by responding anonymously (via post-it note) to the prompt: “How have you been impacted by mental illness?” The prompt is deliberately vague to allow deputies to project their experiences onto the metaphorical blank page. The deputies’ candid responses began to pour in; week after week, the responses continued to address a fundamental fact of mental illness—it affects everyone. Figure 1 includes excerpts from the deputies’ day one responses from the 2016–2017 teaching year.

Over the next two instructional days (day two and day three), instructors focus on topics that are not historically emphasized in a general law enforcement curriculum. In accordance with the findings and recommendations of professional literature, including the IACP’s national symposium on law enforcement suicides and mental health, instructors attempt to address two aspects of law enforcement culture that impact one’s ability to serve—communication and suicide.3

Law enforcement officers and executives have a great cultural concern today (from both risk aversion and career survival perspectives) about the public perception of a use-of-force incident involving someone who might have a mental illness. The officer or deputy’s communication skills and strategies are often under scrutiny in a retrospective analysis, and research demonstrates that this can have unintended consequences to the law enforcement officer’s future contacts during calls for service, as well as career longevity.4 Research also demonstrates that difficulties in communication impact law enforcement officers at home (in their own wellness), resulting in a high number of relationship disputes, dissolutions, and divorces.5 LASD’s Psychological Services Bureau receives requests for psychological supports and services that are consistent with this research on officer wellness, and the majority of appointment requests are related to personal relationship issues.

There is a perceived stigma around law enforcement suicide within the field, as well (from fears of loss of job security or being perceived as “weak”), and these beliefs reinforce barriers to treatment for officers who may experience a psychiatric crisis state or ultimately take their own lives.

In order to address these two identified law enforcement cultural issues, the course teaches different tactical communication concepts—some of which are similar to elements of crisis negotiations—and approaches the concept of suicide from an epidemiology perspective; a clinical perspective; its different presentations in calls for service (subject who is suicidal, completed suicides, suicide by cop, murder-suicides); and lastly, the uncomfortable topic of law enforcement suicides. The instructors discuss the impacts that this loss has upon the department members and ways to discretely obtain help for those in need. The second day of instruction concludes with a somber but impactful tone, and students are often seen talking with one another as they leave class about their personal experiences with the topics discussed.

On day three, there is again significant exposure to emotionally based learning—the LASD Homeless Initiative Program lieutenant provides an introduction to a progressive countywide program that aims to reduce homelessness in Los Angeles County. The lieutenant shares stories and case photos from recent homeless outreach contacts and shares how his team encountered one of their own (a retired LASD deputy) who was homeless. Subsequent to this presentation, there is a panel of consumer advocacy members from the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI). NAMI panel members include a person with lived experience (with a mental illness) and a family member of a person with lived experience. The panel members discuss their experiences with mental illness and any contacts with law enforcement. They talk openly and candidly with students about their personal experiences, and there is an opportunity for dialogue and discussion with students during a question and answer period. Consistent course feedback indicates that the stories shared by the NAMI panelists and the personal connections between the panelists’ own experiences and the students’ work as deputies makes the classroom learning come to life, allowing the deputies to put a face to the issue. The day’s culminating activity asks deputies to constructively and creatively apply the emotional experiences of the day to something novel: traffic signs and merging.

This exercise occurs after the Communication Skills teaching block, at which time concepts such as Listen Empathize Ask Paraphrase Summarize (L.E.A.P.S.), as adapted from Verbal Judo: The Gentle Art of Persuasion and Grounding Techniques are covered.6 The students are asked to describe the meaning of the yellow “merge” road sign (e.g., merging traffic, share the road, join existing flow, caution of lane-adjacent vehicles). After ample examples have been provided by the class, students are offered by the instructor the concept of their patrol field response as being similar to the road sign. In other words, just as cars need to safely negotiate their entrance into traffic so too do deputies need to assess how to safely integrate themselves into situations that result in calls for service. With regards to the road sign, the symptoms are noted as being the straight arrow on the left side of the sign. The curved arrow on the right side of the sign symbolizes the deputies as field responders.

The students are then asked to refer to the specific symptoms of the psychiatric diagnosis they were assigned to define on day one (Schizophrenia, Bipolar Disorder, Depression, or Autism). They are tasked with describing how they would “join” with the subject of the call. Each diagnosis requires a slightly different approach. For example, it may be indicated to speak in a rapid manner with a person exhibiting symptoms of mania. However, a person who is severely depressed is more likely to connect with someone who is speaking at a slower rate of speed. The students meet in groups to describe how they would use their newly acquired communication skills to join with the person exhibiting psychiatric symptoms. Class instructors visit the four groups that compose the class and provide assistance. Each group later chooses a member who shares the results with the class. Students are reminded to tailor their communication techniques and de-escalation strategies to the needs of the situation: for example, someone diagnosed with schizophrenia may benefit from techniques that account for paranoia or confusion in his or her responses to questions, whereas a person experiencing mania may benefit from techniques that acknowledge his or her emotional state without making the individual more agitated. Perhaps of greatest importance is the expectation that each group will generate communication techniques that differ from the three remaining groups.

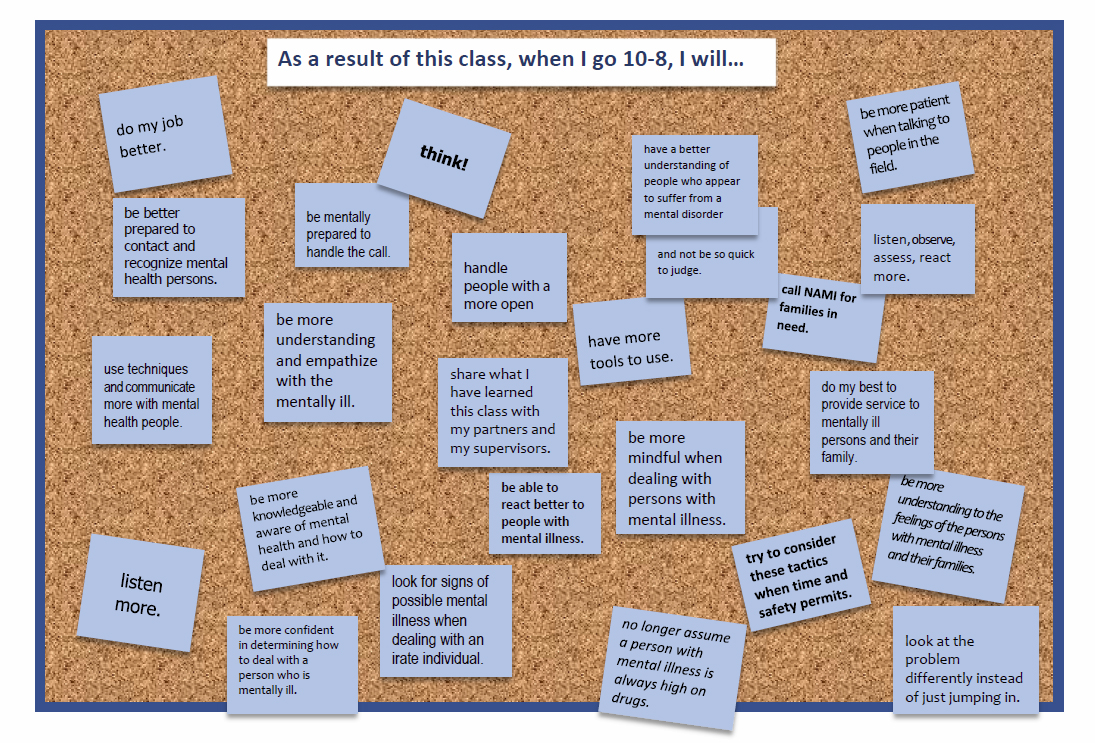

The instructors facilitate the conversation of the concepts from the intense emotional learning to the novel situation and then traverse back to the real world with a self-reflective learning activity responding anonymously (via post-it note) again to a new prompt: “As a result of this class, when I go 10-8 [“in service”], I will…

While the intent of the LASD-CIT course as prescribed by management was to increase the skills and utilization of de-escalation techniques during calls for service involving persons with suspected mental illness, the course evaluations and self-report data consistently note that the culture of law enforcement’s attitude toward mental health is changing. Deputies are learning great amounts of information about mental health and about themselves—and, to quote Maya Angelou, “when you know better, you do better.” As deputies who are LASD-CIT trained are entering the community, they have consistently demonstrated forward progress in the aforementioned paradigm shift highlighted in these three take-away points:

While the intent of the LASD-CIT course as prescribed by management was to increase the skills and utilization of de-escalation techniques during calls for service involving persons with suspected mental illness, the course evaluations and self-report data consistently note that the culture of law enforcement’s attitude toward mental health is changing. Deputies are learning great amounts of information about mental health and about themselves—and, to quote Maya Angelou, “when you know better, you do better.” As deputies who are LASD-CIT trained are entering the community, they have consistently demonstrated forward progress in the aforementioned paradigm shift highlighted in these three take-away points:

1: The success of a future patrol call relies on the individual’s greater and deeper understanding of mental health conditions as one’s empathy and understanding transcends any specific technique that can be taught.

2: “Hooking and booking” is not the only way deputies can protect and serve the community. Deputies are sworn to protect the vulnerable from exploitation, and service to the community may present in many forms.

3: Perhaps terms like “constitutional community policing” is merely the formal way to say “prevention before prosecution” and LASD-CIT deputies will share law enforcement’s subtle mantra through their actions both above and beyond the badge.

Notes:

1 Michael Compton et al., “A Comprehensive Review of Extant Research on Crisis Intervention Team (CIT) Programs,” Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law 36, no. 1 (2008) :47–55.

2 Michael Compton et al., “The Police-Based Crisis Intervention Team (CIT) Model: I. Effects on Officers’ Knowledge, Attitudes, and Skills,” Psychiatric Services 65, no. 4 (2014): 517–522; Michael Compton et al., “The Police-Based Crisis Intervention Team (CIT) Model: II. Effects on Level of Force and Resolution, Referral, and Arrest,” Psychiatric Services 65, no. 4, 523–529.

3 IACP, IACP National Symposium on Law Enforcement Officer Suicide and Mental Health: Breaking the Silence on Law Enforcement Suicides (Washington, DC: Office of Community Oriented Policing Services, 2014).

4 See, for example, Jim Ruiz and Chad Miller, “An Exploratory Study of Pennsylvania Police Officers’ Perceptions of Dangerousness and Their Ability to Manage Persons with Mental Illness,” Police Quarterly 7, no. 3 (September 2004): 359–371; IACP, Building Safer Communities: Improving Police Response to Persons with Mental Illness (Alexandria, VA: 2010) ; IACP, Improving Police Response to Persons Affected by Mental Illness: Report from the March 2016 IACP Symposium (Alexandria, VA: 2016).

5 See for example, IACP, IACP National Symposium on Law Enforcement Officer Suicide and Mental Health; President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing, Final Report of the President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing (Washington, DC: Office of Community Oriented Policing Services, 2015), 61; and Brett Chapman, “Supporting Officer Wellness Within a Changing Policing Environment: What Research Tells Us,” The Police Chief 83 (May 2016): 22–24.

6 George J. Thompson and Jerry B. Jenkins, Verbal Judo: The Gentle Art of Persuasion, Updated Edition (New York, NY: HarperCollins Publishers, 2013).