In the never-ending search for ways to combat crime more effectively, one thing is clear: the ideal solution is to prevent crimes from occurring in the first place. Since the 1990s, many law enforcement agencies around the world have been using some form of intelligence-led policing for crime prevention.

After nearly three decades, however, there is still much controversy and, surprisingly, not much empirical evidence to either support or discredit this data-driven approach to crime prevention. Nevertheless, agencies that have implemented intelligence-led policing have reported compelling results.

So, where does intelligent policing stand today? Is it truly a viable, practical approach to crime prevention? And can it be implemented successfully while avoiding issues like profiling?

Defining Intelligence-Led Policing

When it comes to data-driven law enforcement, two approaches come to mind: intelligence-led policing and predictive policing. While these approaches are not mutually exclusive, there is a difference. Predictive policing uses computers to analyze the big data regarding crimes in a geographical area in an attempt to anticipate where and when a crime will occur in the near future.1 While it does not go so far as to identify who will commit the crime, it does pinpoint hot spots to help law enforcement anticipate the approximate time of day and area of town where police might anticipate another crime. Armed with this information, police can be placed more strategically to either thwart a crime in progress, or even better, prevent a crime from taking place.

Intelligence-led policing, on the other hand, attempts to identify potential victims and potential repeat offenders, then works in partnership with the community to provide offenders with an opportunity to change their behavior before being arrested for a more severe crime.2 According to the U.S. Department of Justice, intelligence-led policing is “a collaborative law enforcement approach combining problem-solving policing, information sharing, and police accountability, with enhanced intelligence operations.”3 It is designed to guide policing activities toward high-frequency offenders, locations, or crimes to impact resource allocation decisions. An important component of intelligence-led policing is that it encourages—and, arguably, depends on—collaboration among various agencies and the community, including not only local police, but other local law enforcement, the FBI, homeland security agencies, and even probation and parole officers.

In short, predictive policing is concerned with where and when crime may happen, while intelligence-led policing, which often includes predictive policing, focuses on preventing victimization.

Data Is King: How Intelligence-Led Policing Works

Although today’s data-driven approaches incorporate sophisticated technology and analysis, predictive policing has been in use for decades, albeit in a more rudimentary form. Police have long used information about crimes in a particular area to identify patterns and anticipate where the next crime is likely to occur. With the advancements in technology, agencies now use computers and data models designed to track patterns, along with additional factors, such as time of day, weather, geography, and “aftershock” areas—those in which a crime has been successful and are ripe for repeats of the same crime (e.g., gang retaliation)—to build complex models that identify the potential for future crimes.4 Law enforcement can then focus their resources on these hot spots.

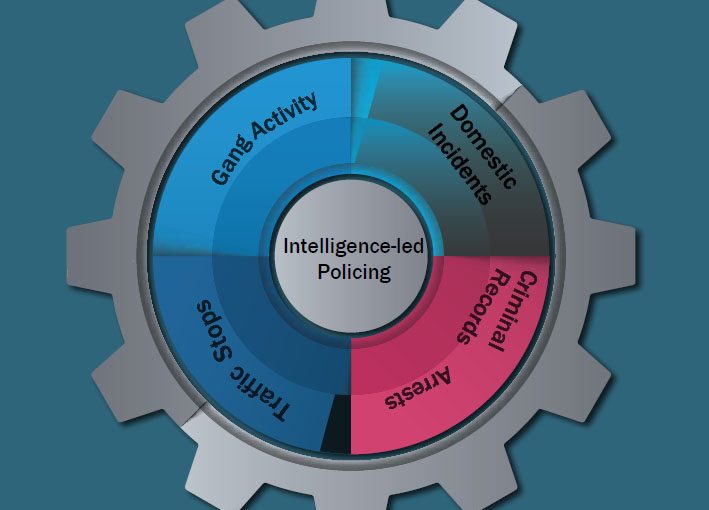

Likewise, intelligence-led policing leverages data. The data on which it focuses, however, are already in the law enforcement agency’s system, and the analysis centers around an individual, not a geographic area. Intelligence-led policing gathers domestic incidents, arrests, criminal records, traffic stops, and gang activity, and allows law enforcement to run analytics against those data. These analytics help law enforcement identify offenders who are more likely to be repeat offenders of a particular crime or group of crimes. Law enforcement can then track those individuals, observing when they move from one class of offense to another. If an offender repeats an offense, police are alerted of that individual’s history, giving them an opportunity to intervene in an effort to prevent more criminal activity.

Theory Meets Reality: Does It Really Work?

Intelligent-led policing sounds very promising in theory, but does it work in the real world? As evidenced by the agencies across the United States who have been using it for the past decade, the answer is yes. What do statistics say?

• In 2012, the RAND Corporation performed an independent study of the use of predictive technology by the Shreveport, Louisiana, Police Department and concluded that “the program did not generate a statistically significant reduction in property crime.” However, the study acknowledged that it looked at only a few districts over a limited time period, which weakened the statistical significance of the study.5

• A 2014 paper published by the American Statistical Association in 2015 studied the use of predictive policing algorithms versus the use of dedicated crime analysts in three divisions of the Los Angeles, California, Police Department and two divisions of the Kent, United Kingdom, Police Department. They determined that models predicted 1.4 to 2.2 times as many crimes as the dedicated analyst and led to an average 7.4 percent reduction in crime as a function of patrol time.6

• In another example, the police force in High Point, North Carolina, applied intelligence-led policing to domestic violence offenders and found these offenders were often connected with other criminal activity, such as drugs, assault, and robbery.7 Domestic violence offenders have a tendency to believe their chances of being caught are very low because only one out of every five incidents are reported. However, knowing that perpetrators of one type of crime are likely to commit other types of crime makes it easier for law enforcement to track and identify these individuals if they are picked up for other crimes. When this happens, the police take the opportunity to warn them of the consequences of continued violence and, hopefully, deter them from further abuse.

High Point has been successful in applying this same technique to gang intervention.8 When one gang is attacked, police know there will often be retaliation, so they talk to the members of both gangs and give them a deterrence message, telling them what to expect from law enforcement if retaliation does occur.

While these examples show the potential successes of intelligence-led policing, it’s important to remember that a key to measurement in all results is found in agency participation. As discussed in the Shreveport example, the limited data use by only a handful of districts reduced the significance of the study’s findings.

Chicago Police Department: Reducing Gun Violence with a “Strategic Subjects List”

The Chicago, Illinois, Police Department (CPD) has used intelligence-led, predictive technology to reduce gun violence based on prior arrests, gang membership, and other factors using a Strategic Subjects List (SSL) of people estimated to be at highest risk of being involved in gun violence—either as a perpetrator or a victim.9 Police warn the individuals on the SSL that they are being monitored. Analysis revealed that more than 70 percent of those who were shot and more than 80 percent of those arrested for shootings were on the SSL. The researchers also found that more than 40 percent of homicide victims had been arrested together with a group of individuals who, combined, made up only 4 percent of the population in the community of 82,000.

Another RAND study concluded that individuals on the SSL were no more or less likely to be a victim of gun violence, although they are more likely to be arrested for gun violence.10 However, the Chicago Police Department publicly disputed that study, citing the following problems:

• It did not evaluate the prediction model itself (as the study indicated), but, instead, focused on the impact of the intervention strategy.

• The study evaluated a much earlier version of the CPD’s Custom Notification intervention strategy and prediction model, which had both evolved significantly.

• The research implied that the model used race, gender, ethnicity, or geography, rather than crime data only.11

Social and Civil Rights Concerns

One of the biggest concerns about intelligence-led policing is that it perpetuates over-policing in minority neighborhoods, rather than eliminating bias.

Opponents of intelligence-led policing have raised the following objections:

• The entire premise is flawed because the computer-based analysis looks only at data entered by humans, and those data are taken from an already biased police force that targets minorities and minority neighborhoods.

• Intelligence-led policing could lead to hostile confrontations between police and residents. For example, if a car theft occurs in one neighborhood, police might consider everyone walking down a street in that neighborhood a suspect and possibly unnecessarily harass them.

• Predicting more crime in a specific neighborhood will encourage more officers to be assigned to that area, which will naturally lead to more arrests. In this scenario, a feedback loop would form, which perpetuates the notion that the neighborhood in question is more susceptible to crime than another neighborhood.

• Tracking specific individuals who are considered potential perpetrators or victims of crime, even when they have done nothing wrong, borders on an invasion of a person’s right to privacy.12

Proponents of intelligence-led policing counter these arguments by citing some compelling details behind areas where the approach has been tested and found to be successful. Computer-based analysis, they claim, eliminates any bias that might be inherent in human-based decisions to target perpetrators and neighborhoods where crimes are predicted to appear.

Tampa, Florida: Community Collaboration

It might come as a surprise to those concerned about social and civil rights that intelligence-led policing has been shown to bring law enforcement and the community closer together when applied appropriately. Take, for example, the Tampa Police Department’s Focus on Four crime reduction program, which was responsible for a 46 percent decrease in crime over six years.13

The Focus on Four concept included strategies to reduce the four most frequently occurring crimes in the city by developing intelligence-based responses that embodied elements such as partnering with the community. Officers became more engaged with the community, which increased public support and reports of crime-related information based on officer-citizen interactions. For example, summer programs were developed in each district to address juvenile-related crime problems that occurred when school was not in session. Within that same six-year period, the program led to a 51 percent reduction in summer crimes.

The Tampa Police Department acknowledged that implementing an intelligence-led policing program could not have been possible without community support and involvement. To encourage this involvement, the department implemented “email trees,” enhanced neighborhood watch programs, and a reverse 911 program to send out information about hot spots to the community.

Not surprisingly, areas with increased police presence have shown a dramatic decline in the incidence of crime. What is surprising is that crime in surrounding targeted areas also decreased. It appears that, instead of pushing criminals into surrounding areas, criminals who are comfortable in one area will avoid committing crimes in unfamiliar territory.

Proponents also claim the greater goal of intelligence-led policing is to prevent a crime from ever happening rather than to catch a perpetrator during or after the crime has been committed. Once a crime occurs, property damage is likely to occur or a person is likely to become a victim. Rather than law enforcement considering everyone a suspect, police in targeted areas will become more proactive in the community by asking residents if they have seen anything suspicious, thereby leading to better community-police relations, as well.

Using Data Is Only Part of the Solution

As important as data analysis is to the goal of preventing crime, it is only one part of the solution. In every instance where intelligence-led policing was implemented, it was one component of an overall strategy that included executive sponsorship, staff reeducation, design and implementation of programs that utilize the data, and more. In every case, the law enforcement agency that implemented the approach also endeavored to ensure people, programs, and equipment were in alignment. Most importantly, however, the human factor is the primary driver of success. Ultimately, people analyze and interpret data; people decide how to use it; and people from agencies work together with people from the community to put these data-driven programs into action and ensure their success.

Conclusion

According to the FBI, the number of crimes reported in 2017 has decreased overall compared with 2016.14 While this is a positive development, the search for ways to advance that trend continues. From improving how we provide health care to unlocking the secrets of the universe, data have made it possible for us to make advances in crime prevention that were never thought possible only a decade ago. While empirical evidence of the effectiveness of intelligence-led policing is still lacking, law enforcement agencies around the world have built a very strong case for this data-driven approach. Pitfalls such as profiling or invasion of privacy are certainly important to avoid, but respecting people’s rights must always be a consideration in any approach to crime prevention. With continued refinement of how data are analyzed, coupled with programming that utilizes data intelligently and encourages agency and community collaboration, intelligence-led policing will continue to strengthen its role as a deterrent to crime.🛡

Notes:

1National Institute of Justice, “Predictive Policing,” June 9, 2014.

2U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Intelligence-Led Policing: The New Intelligence Architecture, September 2005.

3U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Assistance, Navigating Your Agency’s Path to Intelligence-Led Policing (Washington, DC: Global Justice Information Sharing Initiative, 2009), 4.

4Mara Hvistendahl, “Can ‘Predictive Policing’ Prevent Crime Before It Happens?,” Science Magazine, September 28, 2016.

5Priscilla Hunt, Jessica Saunders, and John S. Hollywood, Evaluation of the Shreveport Predictive Policing Experiment (RAND Corporation, 2014).,

6G.O. Mohler et al., “Randomized Controlled Field Trials of Predictive Policing,” Journal of the American Statistical Association 110, no. 512 (2015): 1399–1411.

7Kenneth J. Shultz (police chief, High Point, North Carolina, Police Department), interview by Star Vanderhaar, March 2, 2018.

8J. Brian Charles, “How Police in One City Are Using Tech to Fight Gangs,” Governing, April 11, 2018.

9“Going Inside The Chicago Police Department’s ‘Strategic Subject List,’” CBS Chicago, May 31, 2016.

10Jessica Saunders, Priscilla Hunt, and John S. Hollywood, “Predictions Put into Practice: A Quasi-Experimental Evaluation of Chicago’s Predictive Policing Pilot,” Journal of Experimental Criminology 12, no. 3 (September 2016): 347–371.

11Chicago Police Department, “CPD Welcomes the Opportunity to Comment on Recently Published RAND Review,” press release, August 17, 2016.

12Jennifer Bachner and Jennifer Lynch, “Is Predictive Policing the Law-Enforcement Tactic of the Future?” Wall Street Journal, April 24, 2016.

13Bureau of Justice Assistance, Reducing Crime Through Intelligence-Led Policing (U.S. Department of Justice, 2008), 39.

14FBI, “2017 Preliminary Semiannual Crime Statistics Released,” news release, January 23, 2018.

Please cite as

Rich LeCates, “Intelligence-led Policing: Changing the Face of Crime Prevention,” Police Chief online, October 17, 2018.