Recently, the already-difficult profession of public safety has been made even more challenging by competing political interests, the “defunding” movement, and changing expectations from communities. Communities across the United States are threatening to force change on public safety departments, from citizen oversight panels to funding reductions to complete departmental overhaul. This is a time for self-reflection and to determine if the time is right to make different public safety choices for communities.

The current situation is a result of past decisions. A failed War on Drugs cost over a trillion dollars on interdiction efforts alone, over half the individuals in federal prisons are there for drug-related charges, and overdose deaths are higher than they have ever been.1

In addition to the ongoing social upheaval, the COVID-19 pandemic strained every part of society. In June 2020, 40 percent of all adults reported struggling with mental health or substance use, support structures have eroded, and quarantines and lockdowns have increased many people’s senses of isolation.2 Communities are overflowing with people that need help, and the systems are not built to handle the load.

The U.S. health care system is a volume-based model. The incentives are based on the number of patients seen and the number of procedures done and seldom based on outcomes. The need for care, treatment, counseling, and other services far outpaces health and behavioral health resources.

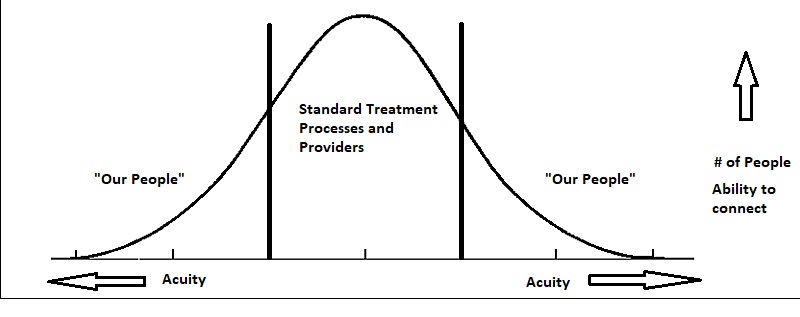

By design, health care systems handle the majority of patients in the middle of the curve, as shown in Figure 1. The system is designed for people with insurance, jobs, and the ability to make appointments on their own. The public safety system seldom sees those people, and when they do, it’s most likely once in a lifetime. The “tails” of the curve are a different story. The individuals on either end of the spectrum struggle with behavioral health disorders, may experience homelessness, and often have one or more chronic medical issues. They commit the crimes associated with social problems: trespassing, shoplifting, disturbances, and so forth. They make up a majority of public safety calls for service, ambulance transports, jail days, and hospital stays.

In deciding how to address these individuals, communities and police agencies have a choice. They can either try and arrest their way out of substance use and complain that hospitals release people with chronic medical conditions back into the community, or they can change and start doing things differently. Communities can create a thriving behavioral health treatment system from crisis response to inpatient facilities with the understanding that jails and emergency rooms are not therapeutic environments. Public safety professionals play a critical role in any solution, but their current role is far too expansive.

Defining where public safety actually is needed can lead to addressing community social problems with community-based solutions. In-progress crimes, medical emergencies, fires, and violence clearly call for public safety involvement. But what about welfare checks, incidents involving mental illness or homelessness, or crimes clearly committed as a result of substance use? There are evidence-based programs being used across the globe that incorporate street-level solutions to address these issues, including the following examples:

- The CAHOOTS program in Eugene, Oregon, is a community responder program that sends a medic and a clinician to answer certain police calls for service, including those that involve welfare checks, substance use, and a variety of other social issues that do not require the skill of a commissioned police officer. In 2019, they responded to 24,000 calls for service (20 percent of the total call volume) with only 150 of those calls needing a commissioned officer.3

- Many communities have adopted co-responder programs that pair a specially trained officer with a mental health clinician or other civilian resources. They have been extensively studied and replicated in numerous jurisdictions in one form or another.4

- Pre-arrest diversion programs have become more prevalent since 2011, when Seattle, Washington, started the first Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion (LEAD) program. There are several different pathways for pre-arrest diversion, from deflection to pre-booking programs, but all facilitate connections to harm reduction–based behavioral health treatment to address the root cause of the individual’s interaction with police.

Case Study: Longmont, Colorado

The City of Longmont, Colorado, believes programs like those discussed previously are most successful when based in public safety and supported by intensive case management. Longmont’s programs follow that model. There are four “pathways” to combat the public health crises of substance use disorders (SUDs) or untreated mental health issues, all of which are supported by Longmont’s intensive case management team. The goal is to reduce the harm to the individual and the community by helping individuals address their addictions and manage their mental health issues. The programs work to reduce the reliance on the criminal justice system for handling these issues and minimize the social and health impacts of behavioral health issues by helping one individual at a time.

LEAD Program

In the City of Longmont, police officers use their discretion to divert or refer individuals struggling with addiction into a harm reduction–based case management program. All LEAD referrals must come via City of Longmont police officers; this is based on the understanding that police officers know their communities and are the best judges of who is an appropriate referral into LEAD. Officers can divert any charge related to an underlying addiction, not just possession charges. The charge could be shoplifting to support an addiction, a trespass, or a disturbance as a result of intoxication, and other charges with the root cause of a substance use disorder. If officers develop probable cause, they will offer the individual a choice to meet with a case manager within 14 days and complete an assessment in exchange for dropping the charge. If a case manager is available, her or she will meet the individual and the officer on scene. If the individual does not complete the assessment, the charge can be revisited (this happens very rarely). All other interactions or previous interactions with the police are handled as normal.

Officers can also refer an individual into LEAD without developing probable cause through a “social referral” process. The goal is to break the arrest and jail cycle and get individuals struggling with SUD into Longmont’s intensive case management services. Public safety–based case managers utilize an assessment to determine individualized needs and work with community behavioral health partners to meet those needs. Case managers then use a community-based outreach philosophy to “meet them (the individuals) where they’re at” and develop individuals’ capacity to confront addiction and build life skills.

Officers can also refer an individual into LEAD without developing probable cause through a “social referral” process. The goal is to break the arrest and jail cycle and get individuals struggling with SUD into Longmont’s intensive case management services. Public safety–based case managers utilize an assessment to determine individualized needs and work with community behavioral health partners to meet those needs. Case managers then use a community-based outreach philosophy to “meet them (the individuals) where they’re at” and develop individuals’ capacity to confront addiction and build life skills.

CORE Team

Longmont’s Crisis, Outreach, Response and Engagement (CORE) Team is a primary response co-responder team that is dispatched to mental health–related 911 calls. Once on scene, team members apply their specialized skill sets to divert individuals with behavioral health conditions from the criminal justice system and the emergency room to appropriate treatment and care. The team focuses on building relationships with clients while working to improve their quality of life. The team includes a behavioral health clinician, a paramedic, and a specially trained police officer. The team follows up with all individuals contacted in crisis to ensure referrals are in place and all necessary support structures are there. If needed, continual outreach is done by the team. As the CORE Team sergeant says, “It’s amazing what happens when people find out someone cares about them, and it’s the police department.”

Community Health Program

The Community Health Program serves community members who frequently access treatment through the emergency department (ED) for chronic health conditions, such as diabetes or heart disease, that are more effectively managed in primary care settings. Clients often lack social support and struggle to advocate for their own care or navigate the medical system. Focusing on the whole person, the team works with clients to help determine their needs, build a relationship, and create a lasting connection to a medical home in the community. The team includes a paramedic and a nurse practitioner. The Community Health Program receives referrals from Medicaid and community partners for patients who frequently access treatment through the ED or who are at risk of readmission to the hospital.

Angel Initiative

Longmont’s Angel Initiative offers a helping hand to community members who are experiencing SUD. Individuals seeking treatment can walk into the Public Safety Department to ask for help and apply to the program. They meet with a peer case manager who refers them to one of many addiction treatment options based on their individual needs. Once in treatment, the peer case manager connects participants to resources that can help with housing, employment, and other needs.

Case Management Team

Longmont’s Case Management Team supports all four pathways. Each peer case manager holds 25 to 30 clients in varying degrees of engagement. Upon receiving a new referral, case managers complete forms to help program staff understand the client’s immediate needs. The forms also collect demographic data that program administrators and researchers use to assess implementation of Longmont’s programs.

Case managers approach relationships with clients using a harm reduction philosophy, with a spirit of acceptance, compassion, and respect for autonomy. The client is the expert on his or her needs and has the capability to determine the best approach to creating change. This is not always an easy or intuitive role; however, it does lead to case managers building transparent relationships with clients and truly walking alongside them, working together to improve the clients’ quality of life. This includes providing transportation to vital medical or mental health appointments; coordinating comprehensive care with external community partners (i.e., probation, primary care providers, hospital staff, jail personnel, housing partners/housing authorities, mental health providers, and employment services); linking to housing resources, assisting with applying for eligible benefits and health insurance; and building life skills aligned with the client’s goals. Longmont’s case management philosophy is one of assertive outreach. Case managers work in the community with the clients. The goal is to build a trusting individual relationship that “bridges the gap” when services are unavailable or the individual is not yet ready.

These programs are deeply rooted in community support. Every month, an operational workgroup of community partners (district attorney, police, public defenders, treatment providers, hospitals, public health providers, housing providers, etc.) meet to review new referrals, problem solve individual cases, and develop community solutions for barriers to care. A steering committee provides overall guidance and is composed of the district attorney, the municipal judge, the public defender’s office, the chief operating officer of a local hospital, and a representative from the county public health department.

Outcomes

Longmont continually evaluates the effectiveness of all of its programs, and the city has contracted with an independent evaluator from the University of Colorado to do a three-year study on the programs. He recently delivered the LEAD Evaluation Pilot Report, which showed remarkable results:

- Clients experienced a 59 percent decrease in all contacts with the criminal justice system, including 50 percent fewer arrests.

- Of the LEAD clients who had an arrest record upon entering the program, 35 percent had no arrests after joining LEAD.

- A 25 percent reduction in hospital transports was attributable to peer counseling.

Data show these programs work, and the reason for their success is very simple: individual, human-to-human relationships. This sounds simple, yet sometimes can be so difficult. Call volume, skill sets, departmental philosophies, community priorities, and other competing interests can all be barriers to the most effective solution. Relationships require empathy. Empathy leads to compassion. Compassion leads to connection, and connection builds relationships. Without the ability to understand someone else’s feelings, one can’t be concerned for people and their challenges.

This is a time for self-reflection and to determine if the time is right to make different public safety choices for communities.

It takes only about 40 seconds to create a compassionate connection with another person.5 It can be as simple as “I am here with you.” Longmont’s approach draws from Compassionomics by Dr. Stephen Trzeciak and Dr. Anthony Mazzarelli, as well as the complementary philosophy of Dr. Paul Farmer and the Neurosequential Model of Dr. Bruce Perry.6 The theme of these resources is clear and obvious. Relationships matter, and they matter far more than one may think.

Longmont’s community members are positively impacted by the way they are made to feel during calls for service, especially those with mental health disorders and SUD. The staff approaches each and every individual with the goal of building a relationship. Those relationships build trust, lead to fewer use-of-force incidents, create an openness among public safety staff to learning about and understanding the chronic disease of addiction, and break down barriers to care.

Lessons Learned

Longmont’s programs have been developed over a seven-year period, and many things were learned along the way. The programs continually share information and ideas with programs in other cities and regions, committed to helping partner agencies in any way possible.

The lessons learned in developing Longmont’s Public Safety Diversion programs include the following:

- Relationships matter. Change the approach and overall philosophy of how to approach individuals with mental health issues and SUD. Every call for service is an opportunity to build a relationship.

- Build the case management system first. This was the biggest mistake Longmont made at the beginning—focusing on the “inputs” first. In addition to the normal referral volume, there is a small percentage of people who simply won’t be connected to providers, including some of the people with significant mental illness and co-occurring SUD. This means that first responders will become the provider of last resort. Case managers are the long-term support structure, and there needs to be enough of them in place to handle referral volume.

- Use the platform of public safety. Public safety has a unique position in the community as a connector and convener. As a community, it is important to understand expectations and outside influences, as well as those factors than can and cannot be controlled. Where can the community itself be the solution? What are the unique needs of the community and what are the specific challenges? For departments that are buried by call volume, start by discussing possible ways to reduce calls for service. For instance, mobile integrated health care programs are a great fit for hospital systems and EMS providers.7 Additionally, co-responder programs can significantly reduce the volume of patrol calls for service.

- Make it easy for the responders. Referrals are the lifeblood of these programs; make it easy for responders to refer people. Utilize on-call phones for case managers and community health programs so patrol officers and fire crews can connect immediately with diversion program staff. Take email referrals and do any assessments through the case managers, not officers or fire crews.

- Just do it. Every community needs these programs right now. With a small investment in one case manager, a police agency can start a small pre-arrest diversion program (target the top 10 municipal offenders). Repurpose or cross-train paramedics to be community paramedics and start visiting anyone in the community with six or more emergency room visits in a given time frame. Don’t overanalyze it. Longmont changed its programs numerous times, and they are still evolving and growing.

- Hire directly through public safety as much as possible. Almost all of Longmont’s diversion program staff work directly in our public safety department. This has numerous benefits. The team atmosphere and ability to build trust is much easier and longer lasting. Team members can avoid most HIPAA information sharing issues, and the agency can change policy when needed. An early iteration of Longmont’s co-responder program utilized a contract provider, and changing policies and procedures was extremely difficult, even when safety related (e.g., the agency wanted clinicians to wear ballistic vests and take defensive tactics training, but the contractor wouldn’t allow it).

Longmont’s programs are all examples of how complementary skill sets can offset the current requirements of public safety personnel. Reducing the overwhelming expectations and consequences is well within reach.

Drawing again from Trzeciak and Mazzarelli, research shows that compassion is a powerful restorer of hope, and hope flowing from compassion is vital to survival.8 Empathy for one another will lead to compassion. With compassion, people can start conversations and connect with each other. Those connections lead to relationships that will bring change.

Notes:

1 Glen Olives Thompson, “Slowly Learning the Hard Way: U.S. America’s War on Drugs and Implications for Mexico,” Norteamérica 9, no. 2 (2014): 59–83.

2Mark É. Czeisler et al., “Mental Health, Substance Use, and Suicidal Ideation During the COVID-19 Pandemic—United States, June 24–30, 2020,” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, August 14, 2020.

3White Bird Clinic, “What Is CAHOOTS?” October 29, 2020.

4Bureau of Justice Assistance, “Learning: Police Mental Health Collaboration (PMHC) Toolkit”; Ashley Krider et al., Responding to Individuals in Behavioral Health Crisis via Co-Responder Models: The Roles of Cities, Counties, Law Enforcement, and Providers (Policy Research, Inc., and National League of Cities, 2020).

5Linda A. Fogarty et al., “Can 40 Seconds of Compassion Reduce Patient Anxiety,” Journal of Clinical Oncology 17, no. 1 (January 1999): 371.

6Stephen Trzeciak and Anthony Mazzarelli, Compassionomics: The Revolutionary Scientific Evidence that Caring Makes a Difference (Pensacola, FL: Studer Group, 2019); B.D. Perry, “The Neurosequential Model Network,” 2018.

7Brooke Roeper et al., “Mobile Integrated Healthcare Intervention and Impact Analysis with a Medicare Advantage Population,” Population Health Management 21, no. 5 (October 2018): 349–356.

8Stephen S. Ilardi and W. Edward Craighead, “The Role of Nonspecific Factors in Cognitive‐Behavior Therapy for Depression,” Clinical Psychology 1, no. 2 (Winter 1994): 138–155.

Please cite as

Dan Eamon, “Changing the Goal to Relationship Building: How to Bring Positive Change to Public Safety,” Police Chief Online, April 21, 2021.