Community policing has ebbed and flowed in popularly and application over the years, though many suggest it is still a viable policing strategy that helps to establish trust and leads to genuine partnerships between communities and the police. The current social climate in the United States calls for a review of police practices and relations with community members, especially regarding people of color.1 The overarching question is whether community policing can bring the communities and police together while also effectively addressing crime. Research on community policing has found that minority communities have reacted positively to community policing initiatives, especially when the community members know or come to know the police officers who serve their communities.2 It is imperative that the profession continue to strive in improving the dyadic relationship between the police and their communities.

One critical realization is that police may be putting forth a one-size-fits-all approach when they use the term “community policing.” However, a real understanding of cultural differences in the communities that police service should inform how police solve policing problems in these communities. Twenty-first century policing calls for new strategies in training, leadership, community involvement and interaction, and officer wellness, as well as the use of new technology and the reliance on credible data.

By understanding the various cultures in multiethnicity and multicultural communities, police agencies can be more effective. Enhancing cultural competence may assist in identifying how police can best address policing problems in their communities, which will also make the police more effective in the viewpoint of the community.

Perhaps, in recognizing that there are historical differences in the treatment of those who are from minority or marginalized races and cultures and acknowledging that the disparate treatment ultimately influences people’s worldviews and perceptions of what is fair and just, one can begin to understand the lack of confidence of an equitable society. It then is reasonable to comprehend why the members of those groups are reluctant to place absolute trust in the police. The acknowledgment of these differences in treatment of various people may allow for a substantial commitment to systemic change and equitable service and justice.3

The History of Policing in the United States

Modern policing (to include community policing), particularly in the United Kingdom and United States, is often said to be rooted in Sir Robert Peel’s Nine Principles of Law Enforcement.4 However, as evidenced by the history of policing in the United States, the concepts espoused by Peel have not always been relevant. This divergence between UK and U.S. policing can be seen to the types of 19th-century crimes that were identified in Europe in comparison to the so-called crimes that were designed to control the behaviors of minorities and maintain the economic wealth of land and slave owners in the United States during the same time frame. It then is no surprise that many have questioned the concept of community policing and its success, particularly in minority and multicultural U.S. communities. Recent research by the Pew Research Center and Gallup polling data have both consistently found racial differences in the public’s views of how police deal with minorities.5

While literature points to an increase in community policing efforts, it’s unclear if these efforts address the gaps between the demographics of a community and that of its police force, a prominent theme in coverage of Ferguson, Missouri.6 Some experts and advocates say that, rather than addressing real issues such as demographic disparities, community policing is merely a euphemism. An op-ed by activist Alyssa Aguilera and sociology professor Alex Vitale suggests,

[C]ommunity policing means more intensive and invasive policing of minor disorderly behavior serves to criminalize mostly people of color without dealing with the underlying causes of this behavior like poverty, homelessness, problematic drug use, mental health issues, and more.7

In a gentler, but still critical view, journalist Christopher Moraff contends,

While many of these initiatives [community policing] have borne fruit, the program has challenges.” Since community policing is more a philosophy than a standardized set of practices, departments have a lot of flexibility in how the term gets translated on the street. And they don’t always get it right.8

Another journalist, Natalia Megas references Obama’s 21st Century Police Task Force, arguing,

This task force reignited public enthusiasm around the term “community policing.” While this term is currently a media buzzword used to describe any positive police engagement with the community, it’s not a new concept. Where does “community policing” come from, and what does it mean? And, more importantly, is it effective?9

One must wonder if community policing is being appropriately applied or is applied differently when used in the minority and multicultural communities. It would be foolhardy to suggest that all community policing strategies are thriving in the majority of the White U.S. communities, although most would agree that the relationship with the police in White communities is more successful than in minority communities, particularly Black communities, for some of the reasons outlined previously. One could argue that it was not the goal of Peel’s Nine Principals of Law Enforcement to address the various races, ethnicities, and religions found in the United States today. Therefore, the concept of community policing derived from Peel’s principles may be inapplicable in its entirety to modern community needs and scenarios. The challenges and mistreatment minority communities were forced to face is a feasible justification for the community policing’s ineffectiveness.

One must wonder if community policing is being appropriately applied or is applied differently when used in the minority and multicultural communities. It would be foolhardy to suggest that all community policing strategies are thriving in the majority of the White U.S. communities, although most would agree that the relationship with the police in White communities is more successful than in minority communities, particularly Black communities, for some of the reasons outlined previously. One could argue that it was not the goal of Peel’s Nine Principals of Law Enforcement to address the various races, ethnicities, and religions found in the United States today. Therefore, the concept of community policing derived from Peel’s principles may be inapplicable in its entirety to modern community needs and scenarios. The challenges and mistreatment minority communities were forced to face is a feasible justification for the community policing’s ineffectiveness.

Adding Cultural Competence to Community Policing

One of the biggest mistakes that police departments can make is to establish and maintain an organizational culture that operates as if all communities are the same and cultural variations and differences do not exist. The practice of dismissing cultural differences diminishes community policing efforts. Asserting that the police who enforce the law are colorblind is, on its face, draconian. This assertion not only diminishes or attempts to omit the history of policing in the United States, but it also suggests that there are no cultural differences in racial or ethnic minority communities. Acknowledging cultural differences, enhancing cultural competence, and educating police on the history of U.S. policing can improve community policing efforts.

For community policing strategies to be effective in all communities, police agencies must prepare their members—sworn officers and civilians—to serve diverse communities by acknowledging cultural differences and enhancing cultural competence through education. If not, agencies are sending officers in the various communities ill-equipped to police in what may be the most intricate era in U.S. policing.

Overall, police effectiveness is critical for police leaders striving to obtain efficacy; the profession must ensure officers are equipped both mentally and physically in driving workable community policing strategies. These community policing strategies must be developed in collaboration with the communities, keeping in mind that addressing the communities’ concerns shall be the goal of said strategies.

Training Officers in Cultural Competence

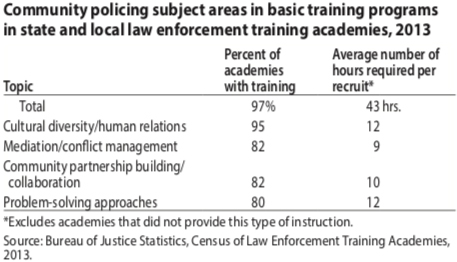

Officers are often equipped with not only hard skills but also soft critical skills. Indeed, it would be unconscionable to expect the police to engage in their duties without proficiency in firearms, driving, and self-defense (hard skills); however, police leaders and trainers have not placed the same emphasis on soft skills, i.e., tools to engage in critical thinking that lead to proper decision making and problem-solving with the community. Although, basic police training indicates some of these skills are present in academy curriculum throughout the United States, the lack of cultural competence (defined as learning about history and shared characteristics of different groups and cultures and using this knowledge to create bridges and increase understanding of other groups and cultures) or U.S. policing history in those curricula is apparent.10 (See Table 1.) Police leaders should set clear expectations among subordinates and trainers to ensure that standards of performance are being set, measured, and awarded appropriately throughout their organization in relation to the constant application of said soft skills.11

Law enforcement officers face an ever-changing landscape of local and global challenges. They must continually hone their skills by taking advantage of educational opportunities and gather knowledge to confront these issues and protect the public.12 Increasing officers’ understanding of the history of U.S. policing and enhancing cultural competence through training can increase effective community policing, particularly in the minority neighborhoods.

| Table 1: Community Policing Subjects |

|

Cultural competence allows police to apply a proper context while operating in a culture or community in which they may be less familiar. Cultural competence contributes to decision making and problem-solving, and most importantly, it helps officers apply accurate judgment in culturally diverse communities. But, in the unequal, divisive settings in which so many vital community-police exchanges occur, police problem-solving cannot afford to be limited by a lack of cultural understanding.

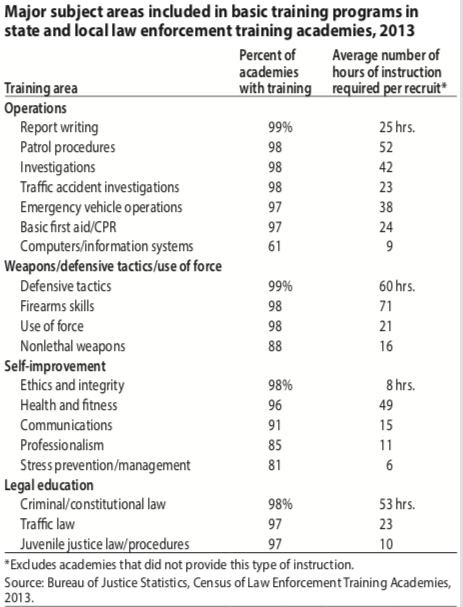

Unlike other service professions, such as the health-related professions, public service administrations and police training programs have not focused on cultural competence despite suggestions from scholars and researchers to do so. Police departments should integrate cultural competence curriculum in their academy training for police cadets and for other members of the police department who are not educated in cultural competence. Additionally, to enhance the learning and increase police effectiveness in minority communities, police must not only focus on cultural competence but include the history of U.S. policing so as to significantly strengthen community policing strategies and initiatives. Currently, neither the history of U.S. policing nor cultural competence is included in the major subject areas in basic training programs in law enforcement training academies across the United States (see Table 2). Armed with cultural competencies, police can readily address a plethora of complex issues with a critical understanding of how police must operate hand-in-hand with all communities despite their innate cultural differences. This understanding will increase effective policing from both the viewpoint of police and community, particularly in minority and multicultural areas.

| Table 2: Subject Areas Included in Basic Training Programs |

|

Community Partnerships

Can community policing bring the community and the police together while reducing crime? Can education on the history of U.S. policing and cultural competence increase effectiveness but instill trust and legitimacy in minority and multicultural communities? The significance of cultivating the capacity to learn culture capacity can be found in the words of a police officer participating at one of a series of community-police forums who averred that “if police don’t start having relationships, police will have an intifada.”13

Community policing is a strategy, and as the demographics of communities change, so must the strategy. While active community policing strategies and initiatives increasing trust and legitimacy in the community and reducing crime are essential, an approach to reduce jeopardizing life and limb during legal community-police confrontations is the goal. The preservation of life while maintaining a society of public order must be the mandate. Establishing a genuine partnership with the community by educating officers in the history of U.S. policing and enhancing cultural competence while simultaneously engaging in community policing strategies and initiatives can help the police become more effective, particularly in the eyes of the communities they serve. d

Notes:

1 Keven L. Nadal et al., “Perceptions of Police, Racial Profiling, and Psychological Outcomes: A Mixed Methodological Study,” Journal of Social Issues 73, no. 4 (2017): 808–830.

2 Aaron J. Diehr and Justin T. McDaniel, “Lack of Community-Oriented Policing Practices Partially Mediates the Relationships between Racial Residential Segregation and ‘Black-on-Black’ Homicide Rates,” Preventative Medicine 112 (July 2018): 179–184.

3 Nadal et al., “Perceptions of Police, Racial Profiling, and Psychological Outcomes.”

4 Law Enforcement Action Partnership, “Sir Robert Peel’s Policing Principles.”

5 Otis S. Johnson, “Two Worlds: A Historical Perspective on the Dichotomous Relations between Police and Black and White Communities,” Human Rights Magazine 42, no. 1

6 Josiah Bates, “Does ‘Community Policing’ Reduce Harms or Enable More of the Same?” Filter, October 10, 2018.

7 Alyssa Aguilera and Alex S. Vitale, op-ed, Gotham Gazette.

8 Christopher Moraff, “The US Has Spent $14B on Community Policing—What Have We Learned So Far?” Yes! (Summer 2015).

9 Natalia Megas, “Community Policing Is Back in Vogue. But Does It Work?” Freethink, April 15, 2019.

10 Ruth G. Dean, “The Myth of Cross-Cultural Competence,” Families in Society: The Journal of Contemporary Social Services 82, no. 6 (May 2001): 623–630.

11 John P. Decker, “A Study of Transformational Leadership Practices to Police Officers’ Job Satisfaction and Organizational Commitment” (EdD diss., Seton Hall University, 2018).

12 Cynthia L. Lewis, “Discussion as a Strategy for Educating Law Enforcement Officers,” Law Enforcement Bulletin, June 6, 2019.

13 Rachel Wahl, “The Inner Life of Democracy: Learning in Deliberation between the Police and Communities of Color,” Educational Theory 68, no. 1 (February 2018): 65–83.

Please cite as

Damon J. Brown, “Community Policing in Multicultural Communities: Adding Key Components to Make It Successful,” Police Chief Online, August 19, 2020.