Police leaders sometimes find themselves in precarious positions, balancing the need for transparency and improvement with the potential for public dissatisfaction and criticism. However, two forward-thinking police chiefs recently took a bold step by initiating a groundbreaking study on contagious fire, demonstrating that teaming up with researchers can lead to better policing practices and ultimately benefit the communities they serve.

Chief Steve Hebbe of the Farmington, New Mexico, Police Department and Chief Jason Potts of the Las Vegas, Nevada, Department of Public Safety collaborated with a team of researchers to investigate the phenomenon of contagious fire—a situation where officers may discharge their firearms in response to the stimulus of gunfire from fellow officers rather than based on an independent assessment of the threat.

The study originated from Chief Hebbe’s observation during a shooting review. He noticed that a substantial volume of rounds had been fired during an incident involving multiple officers. His observation prompted him to seek answers to a longstanding question in law enforcement: Does contagious fire exist, and, if so, what can be done about it? Occurrences like these are sometimes referred to as “sentinel events,” which are critical incidents (like a use-of-force situation) that can lead to a “root cause analysis,” which is a systematic process to identify the fundamental reasons behind a problem or event.1

As Chief Hebbe started to seek answers, he could not find definitive scientific information. Chief Hebbe reached out to policing researcher Dr. John DeCarlo of the University of New Haven. Excited at the opportunity to work with the chief, Dr. DeCarlo, a retired police chief himself, contacted his colleagues: Dr. Eric Dlugolenski (Central Connecticut State University) and Dr. David Myers (University of New Haven). All three men agreed that working on this issue together with Chief Hebbe was a great opportunity to engage in a root cause analysis to understand more about contagious fire. This was the beginning of a multisite, multistate, randomized controlled trial experiment to test the contagious fire thesis.2

Chief Hebbe explained,

About a year before the start of the study, we had an officer-involved shooting in our downtown area. There were five officers involved, which was more than any of our previous shootings. All told, our officers fired approximately 46 rounds. Previous shootings saw officers firing anywhere from two to five rounds per officer. In this case, some officers fired 10-14 rounds. In our review, we noted this significant difference and wanted to know if the number of officers involved in the shooting played a role.3

As the project began and data collection started in New Mexico, Colorado, and Arizona, Dr. Dlugolenski contacted his fellow NIJ LEADS scholar, Chief Jason Potts, at the City of Las Vegas Department of Public Safety to ask if he would also be interested in having his department take part in the research. Chief Potts, a practitioner researcher himself, jumped at the chance to get involved.

“The experience proved valuable not only for the research findings but also for exposing officers to the scientific process and fostering a culture of inquiry within the departments.”

The two chiefs’ decision to pursue this research demonstrate a commitment to creating learning organizations. These are departments that continually expand their capacity to create their future by constantly studying and practicing, enabling them to learn from both successes and failures to improve strategies and operations within their departments—embodying the ideal of a continuous learning organization.4 By recognizing a sentinel event and pursuing a root cause analysis approach, they sought to identify fundamental reasons for unwanted outcomes and critical errors, with the goal of preventing similar incidents in the future.

Chief Potts emphasized the importance of this approach:

The study of the contagion fire phenomenon is a significant challenge for both policing agencies and communities and highlights the necessity of evolving and adapting through continuous learning. The benefits of “walking the walk” and illustrating to the hardworking and courageous members of our department the importance of targeting, testing, and tracking outcomes/data sets to be more effective, just, and empathetic—outweigh any potential concerns.5

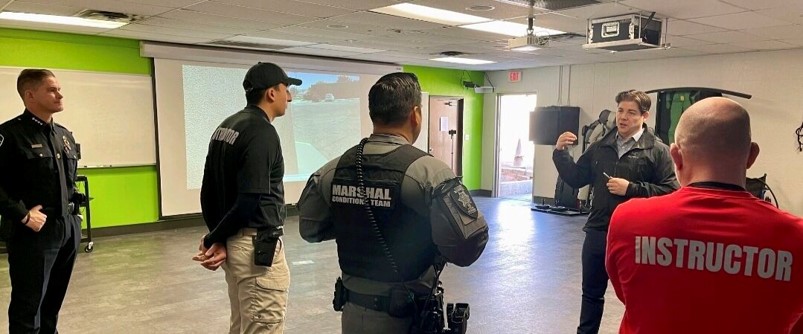

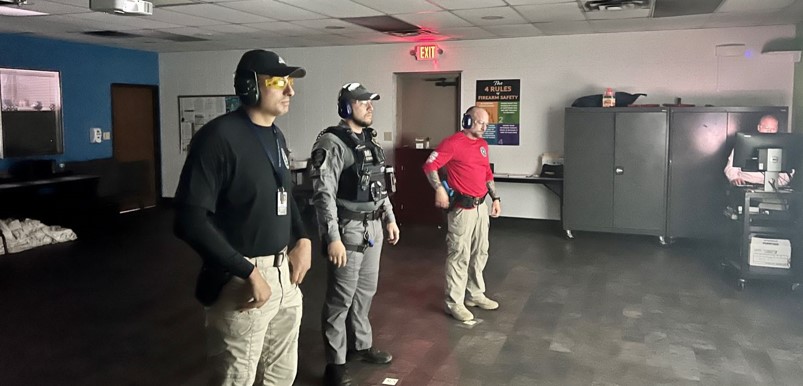

The study involved creating a realistic simulation scenario featuring a potentially armed suspect. Officers were randomly assigned to either a control condition, where confederate officers did not fire their weapons, or a test condition, where confederate officers fired their weapons on cue. The experiment aimed to determine whether the presence of peer officer gunfire influenced individual officers’ decisions to shoot and the number of rounds fired.

Conducting such a study required careful planning and execution. Both departments assigned project coordinators to manage logistics, ensure safety protocols, and maintain the integrity of the research. Sergeant Nicholas Bloomfield (since retired) served as the coordinator for Farmington Police Department. Sergeant Bloomfield was instrumental in identifying and attaining the training rounds used in the experiment. Sergeant Marcus Diaz (since retired) served as the coordinator for the Las Vegas Department of Public Safety. The coordinators worked closely with the researchers to secure appropriate venues, equipment, and participants from neighboring agencies.

Conducting such a study required careful planning and execution. Both departments assigned project coordinators to manage logistics, ensure safety protocols, and maintain the integrity of the research. Sergeant Nicholas Bloomfield (since retired) served as the coordinator for Farmington Police Department. Sergeant Bloomfield was instrumental in identifying and attaining the training rounds used in the experiment. Sergeant Marcus Diaz (since retired) served as the coordinator for the Las Vegas Department of Public Safety. The coordinators worked closely with the researchers to secure appropriate venues, equipment, and participants from neighboring agencies.

One of the challenges faced was maintaining the confidentiality of the study’s true purpose to prevent skewing the results by introducing biases. As Chief Hebbe noted, “What made it a bit different, however, was not being able to tell the officers what we were testing for since we feared it might change how they acted during the tests.”

Despite these challenges, the trials were successfully conducted with high participation rates from their officers. The experience proved valuable not only for the research findings but also for exposing officers to the scientific process and fostering a culture of inquiry within the departments.

Chief Potts reflected on the impact of the study:

As a result of our partnership with the research team, we are currently working [on] implementing ICAT (integrating, communications, assessment, and tactics) in our city jail and corrections officers as well as expanding it on patrol and within our specialized assignments. As we learned from the contagious fire study, humans are likely to respond to stimuli for numerous reasons, but it is our responsibility as trainers to teach best practices that aim to reduce the use of deadly force. We don’t want to just teach best practices but target, test, and track the data to ascertain whether it is having the intended impact.”

The willingness of these chiefs to subject their departments to scientific scrutiny demonstrates a commitment to evidence-based policing and continuous improvement. By partnering with academic researchers, they have set an example for other police agencies to follow.

Chief Hebbe emphasized the importance of such collaborations:

Law enforcement does not often embrace partnerships with academia, and that is a seriously missed opportunity for our profession to grow and learn. There is so much data being collected by police agencies, and we should embrace the chance to learn whatever we can.

The study’s findings (which are detailed in the October 2024 Police Chief Research in Brief column) have implications for police training, policy development, and accountability measures. By understanding the factors that may contribute to contagious fire incidents, departments can develop more effective strategies to mitigate risks and improve officer decision-making in high-stress situations.

Chief Potts highlighted the broader impact of this research:

By actively seeking to understand the factors that contribute to contagious fire, policing agencies can develop more effective policies and training programs aimed at minimizing its occurrence. Incorporating stimuli associated with contagious and reflexive fire in training simulations and implementing de-escalation techniques are all crucial steps in addressing this phenomenon.

The experience of these two departments offers several key lessons to police leaders:

- Embrace root cause analysis: Use near-miss incidents as opportunities for proactive improvement rather than sources of blame.

- Foster transparency: Be willing to open the department to scrutiny, as it can build trust with the community and lead to valuable insights.

- Develop research partnerships: Collaborate with academic institutions to bring scientific rigor to policing practices.

- Cultivate a learning organization: Create an environment where continuous innovation and adaptation are the norm.

- Invest in research and development: Consider establishing research and development units within departments to conduct practical, impactful research.

As a former police chief with 34 years of experience in law enforcement, Dr. DeCarlo can attest to the value of embracing research and evidence-based practices. Throughout his career, he witnessed firsthand the challenges that arise when departments operate based on tradition or intuition rather than empirical evidence. The courageousness demonstrated by Chiefs Hebbe and Potts in pursuing this study is commendable and should serve as an inspiration to police leaders everywhere.

The intersection of policing and research has the potential to answer questions that have long vexed the policing profession. By fostering a culture of curiosity and inquiry, police agencies can continually improve their practices and deliver high-quality policing to the communities they serve. This study on contagious fire is just one example of how scientific inquiry can shed light on complex issues in policing.

“It is vital for police leaders to recognize that embracing research and transparency… strengthens their agencies and enhances their ability to provide better service to their communities.”

As the professional moves forward, it is vital for police leaders to recognize that embracing research and transparency does not make them vulnerable; rather, it strengthens their agencies and enhances their ability to provide better service to their communities. By seeking answers to difficult questions, police leaders demonstrate their commitment to excellence and their willingness to evolve in response to new information.

The promise of public protection is a cornerstone of government, and it is the responsibility of police leaders and police researchers to help fulfill that promise to the best of their abilities. This means being open to new ideas, willing to examine their practices critically, and courageous enough to make changes when necessary. The contagious fire study exemplifies this approach and sets a new standard for evidence-based policing. It’s important to note that this type of research partnership is particularly crucial in the United States, where policing is a very local and granular activity. Unlike some other countries, the United States lacks a national police research and development arm. Instead, more than 18,000 police departments largely depend on a limited number of grants each year and private companies that develop new products (that they have a vested interest in selling) to drive innovation and improvement.

This situation underscores why partnerships between police researchers and police departments are important to answering the questions that will lead to more efficient and equitable policing.

The initiative taken by Chiefs Hebbe and Potts to study contagious fire represents a significant step forward in policing’s journey toward becoming a truly evidence-based profession. Their willingness to subject their departments to scientific scrutiny, despite the potential for criticism, demonstrates true leadership and a commitment to continuous improvement. As the profession faces the challenges of 21st-century policing, this kind of courage and curiosity will drive policing forward, ensuring that agencies continue to evolve and better serve their communities. d

Notes:

1National Institute of Justice, NIJ Strategic Research and Implementation Plan: Sentinel Events Initiative 2017–2021 (U.S. Department of Justice, Officer of Justice Programs, 2017); Katherine B. Percarpio, B. Vince Watts, and William B. Weeks, “The Effectiveness of Root Cause Analysis: What Does the Literature Tell Us?” The Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety 34, no. 7 (2008): 391–398.

2Michael D. White and David Klinger, “Contagious Fire? An Empirical Assessment of the Problem of Multi-Shooter, Multi-Shot Deadly Force Incidents in Police Work,” Crime & Delinquency 58, no. 2 (March 2012): 196–221.

3Steve Hebbe (chief, Farmington Police Department, New Mexico), personal communication, July 5, 2024.

4William A. Geller, “Suppose We Were Really Serious About Police Departments Becoming ‘Learning Organizations’,” National Institute of Justice Journal 234 (December 1997): 2–8.

5Jason Potts (chief, Las Vegas Department of Public Safety, Nevada), personal communication July 7, 2024.

Please cite as

John DeCarlo, Eric Dlugolenski, Steve Hebbe, & Jason Potts., “Courageous Leadership: Police Chiefs Drive Contagious Fire Study,” Police Chief Online, October 01, 2024.