It was a candid assessment from the new police chief in Pine Hill, New Jersey, after examining the culture of his agency and engaging in self-reflection: We need to do more to protect our youth.

Chris Winters had just been promoted to police chief in 2012 after 12 years on the force, and the community was still reeling after the arrest of a highly respected citizen—a middle school art teacher, borough councilman, American Legion commander, Municipal Alliance coordinator, high school soccer coach—later indicted on 92 counts of sexual assault and possession of child sexual abuse material involving 17 at-risk boys he targeted over five years at the town’s only middle school.1

At the same time, juvenile arrests, mental illness, domestic violence, and drug abuse were on the rise. An alarming number of students with problems at home were either skipping school or dropping out altogether. More children were running away, some for long periods of time, making them prime targets for sex traffickers and other forms of sexual exploitation.

“No one was asking, ‘Why is this happening?’” said Winters, himself included. “We needed to do something, but we didn’t have the resources or the understanding about the underlying issues for at-risk youth.”

As the new chief, Winters went to Alexandria, Virginia, in 2013 to take a training course for public safety leaders at the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children (NCMEC). More than 3,200 police chiefs, sheriffs, 911 directors and state clearinghouse executives have taken the nationally certified training, now known as “Protect. Reduce. Prevent: Executive Leadership Series (PRPL).” The training covers effective policies, best practices, and emerging trends in missing and sexually exploited children cases.

Participants learned about the free resources NCMEC provides law enforcement to help with these unique and often complex crimes. These include deploying on-site consultants in critically missing child cases (Team Adam), sex offender mapping, geo-targeted poster distribution, analytics, search dogs, technology, family services, case reviews, age progressions, skull reconstructions, and more.

Like the Pine Hill Police Department, most of the 18,000 U.S. law enforcement agencies are small, with just a few dozen officers and limited resources, yet these agencies face many of the same challenges as much larger ones.2

NCMEC instructors encouraged law enforcement leaders to evaluate the culture of their departments and to engage in self-reflection. Above all, they stressed that community engagement and partnerships were the key to success, something desperately needed in Pine Hill.

Winters took the training to heart, and long before the debate over policing took center stage in the United States, he vowed that his department would do things differently and create “a culture of community-based change.”

It wasn’t going to be easy, and building trust in the community and strong partnerships wasn’t going to happen overnight. Winters believes a holistic approach was necessary to improve quality of life for Pine Hill’s citizens and protect their children. A traditional law enforcement approach to issues and needs was not the answer.

With a changing of the guard in some key positions, and the support of Pine Hill’s governing body, Winters helped transform the community. To start, he reached out to residents and key stakeholders, not just asking for their input but for their help. Winters said to the Pine Hill school superintendent, “Just give us 10 years to change the dynamics with the schools and the youth.”

It wouldn’t take the full 10 years. Law enforcement–driven change has been able to transform the definition of community policing, creating new partnerships to provide long-term social services stabilization and achieve community health.

As a result, Pine Hill has experienced a dramatic decrease in juvenile, as well as adult, arrests and in the number of runaways. Index crimes have steadily declined, especially burglaries and thefts. Currently, social service specialists are “embedded” full time at police headquarters, working side by side with officers to assist residents at every point of contact with police.

“It’s basically a culture change,” said Neighborhood Response Officer Martin Brennan, who serves as the police liaison with Pine Hill’s apartment complex managers and its religious leaders. His role was to learn the needs of their tenants and parishioners. “We’d much rather stabilize the individual and see what’s going on – Why are you shoplifting? Did you lose your job? Are you hungry? – rather than have them end up in handcuffs and jail. We’re here to help. We’re asking why.”

The Pine Hill Story

Pine Hill is a four-square-mile borough with the highest elevation in Camden County, New Jersey. In some spots, Philadelphia’s skyline can be seen in the distance. It has easy access to other major hubs, including Newark, Atlantic City, and New York.

Pine Hill was named for its pine trees and hills, once a draw for visitors suffering from tuberculosis who would stroll through its thick pine tree forests and breathe in the crisp, clean air, a soothing balm for their lungs.

When Winters took the helm of the police department, about 10,300 people were living in Pine Hill, a blue-collar and low-to-mid-income community. Of those, about 14 percent lived below the poverty line, and more than half of the 1,864 students enrolled in its two elementary schools, one middle school, and one high school qualified for free or reduced lunches; 80 kids were registered as homeless or housing insecure.3

Ironically, the town once known for its therapeutic benefits was itself ailing, although not everyone acknowledged there were problems, much less a need for change, Winters said. “Because that’s the way we have always done it,” was a common refrain. Initially, there was skepticism and some pushback from the community.

But Pine Hill’s problems were on full display. Scattered around the borough, an estimated 500 residential properties sat vacant, with playgrounds and parks underutilized and in disarray. The only full-service grocery store was shuttered, and there was little commerce. The rise in mental health cases and violent crimes was concerning for such a small town. Sadly, Pine Hill was experiencing one of the highest number of child sexual assaults and child endangerments in the county.

One Pine Hill teenager Winters arrested when he was a patrol officer still haunts him. Her criminal justice system involvement began when she was 13—everything from aggravated assault to thefts to narcotics. She dropped out of school, ran away often, became pregnant. There were incidents of domestic violence with the father of her baby and arguments with her single mother. She was at high risk for sex trafficking. She was arrested at age 19 in Atlantic City on prostitution charges because, at that time, she was legally an adult.

“I was the one arresting her and not asking questions, not asking the why,” said Winters. “Her case is the textbook story of what child sex trafficking looks like.”

Winters was also concerned that his police department would be unprepared if there was a non-family abduction, the rarest type of missing child case that can overwhelm any size police department and take a toll on the community.

During his leadership training at NCMEC, Winters heard the story of six-year-old Morgan Nick who was abducted on June 9, 1995, in a small town like Pine Hill—and is still missing after 26 years.

In painful detail, her mother, Colleen Nick, told the class of law enforcement leaders how Morgan had asked for permission to catch fireflies with her friends during a Little League game they were watching in Alma, Arkansas. That was the last time she saw her child. For more than 26 years, she has never stopped looking for her daughter, who would be 32 today. Year after year, Nick shares her story in the hope that law enforcement will one day find the stranger in the truck who took her daughter and bring Morgan home.4

“There’s not a baseball field I look at and don’t think of Colleen Nick’s story,” said Winters, who has three children. “I thought, ‘My God, if that tragedy happens to us, we need to be prepared, either to prevent it or handle it from Day 1.’”

Winters immediately began preparing his agency, and, in 2014, the Pine Hill Police Department became one of the first two law enforcement agencies in the United States to be certified by NCMEC’s “Missing Kids Readiness Program,” along with the neighboring Gloucester Township Police Department. Since then, both agencies have been recertified and a growing number of agencies around the country are following suit.

To be certified, command staff and all their officers take various required online training. Agencies then adopt the model policy for law enforcement when responding to reports of missing and sexually exploited children that was developed with help from the International Association of Chiefs of Police. Those departments developing their own model policy must have them reviewed by NCMEC staff to ensure compliance with best practices.

Pine Hill and Gloucester Township were the first. Since then, 323 agencies, including law enforcement and 911 communication centers, have taken the training to become as prepared as possible if a child is critically missing from their communities.

It Takes a Borough

Seeing a cluster of police cars outside a school is enough to send pulses racing in any community in this terrifying era of active shooters. Not in Pine Hill. Not anymore.

Today, police cars are a familiar, welcome sight at all four of its schools, where police officers frequently stop by just to say hello to the children or to assist throughout the day—judging a poster contest, showing them how to avoid dangers on the internet and in the medicine cabinet, helping with book and backpack drives, building gingerbread houses with the preschoolers, volunteering along with them on MLK service day, and challenging them on the football field in a Madden video game.

Even as some police departments around the United States are eliminating the School Resource Officer (SRO) position, Winters believed at the time, and is even more convinced today, that the SRO position was key to making the systemic changes in Pine Hill to help its youth and residents—but only if the right person was in the job who could build trust with students and their families and help connect them to the services they need. His choice for SRO, Detective Justin DiGiacomo, reports directly to him.

“We were having so many runaways, we couldn’t keep up,” said DiGiacomo. “Over the last 10 years, it’s changed so much. By trusting us as police officers, we can get them the help they need.”

In fact, the police chief wanted all 22 of his police officers to become part of the “fabric of the day” in Pine Hill’s schools, not there to take punitive actions but to mentor youth and determine why they were running away and getting into trouble, to catch them before they fall. Were their parents struggling to pay bills or put food on the table? Was there mental illness in the family? Were they being abused? What basic needs were lacking at home? What many were lacking was a safe place to go after school.

Heidi Daunoras, the school district’s director of curriculum and instruction, eagerly welcomed Winters’ holistic approach: First stabilize the child, then address the root cause of the chaos in their lives. “We were constantly putting out fires every day,” said Daunoras, who has been with the school district 29 years, including nearly two decades as a teacher. “I would want four Justins,” she said of the high school’s SRO, one for each school.

They weren’t sure if kids would attend, but they considered starting a Game Club in the high school library for two hours after school to provide a safe space where students could be supported and unwind, receiving counseling as needed while engaging with the SRO. They’d provide rides home if transportation was not available. Project Success, as it was named, was worth a try.

Using funds from Camden County, they purchased PlayStations, Nintendos, puzzles, chess boards, and Monopoly games. They kept it simple, setting up six gaming stations with large screens to accommodate four to five kids playing nonviolent video games (like Madden football) and brought in comfortable seating. They opened the doors to any student, or police officer, who wanted to participate, with school counselors starting each session with positive messages, discussing life lessons, and how to set goals and maintain friendships.

But was this unique approach going to fly? It took off.

Once Covid restrictions eased, attendance rose to as high as 65 kids in one day, one-tenth of the entire high school student body, said Daunoras. Most remarkably, kids who always kept to themselves were suddenly socializing, including a teenager who spent the school day tucked inside his hoodie and his headphones. And it was not just the gamers who attended, but the athletes, the artists, all leaving their alliances at the door.

“A lot of these kids were going home to empty houses,” said DiGiacomo, who as SRO is based at the high school but also has a presence in the middle and elementary schools. “Word started spreading. It didn’t matter what clique you ran with. The kids love it. I’m running out of room. I need more gaming systems.”

Rosy Arroyo, the Camden County Youth Services Commission administrator, had been concerned about the escalating number of juvenile arrests in Pine Hill. The county allocated $2,500 toward the start-up of the high school’s Project Success, then an additional $30,000 to purchase more equipment as the club started to expand. “The best part about that program is that it involves everyone,” Arroyo said.

Meanwhile, Brennan, the police department’s neighborhood response officer, concentrated on the Pine Hill community, assessing the basic needs of its residents. There’s usually a reason people commit crimes, he said. They’ve lost a job, they’re battling addiction and need money to buy drugs, they can’t pay their bills.

“Somebody doesn’t just wake up one day and say I’m going to go out and start robbing banks,” agreed Pine Hill Mayor Christopher Green. “If somebody is hungry, you can feed them and stop them from stealing.”

To that point, while juvenile involvement and diversionary efforts were well received throughout the borough, Winters and his police department needed additional social services resources to assist adult residents. Requiring referrals or appointments can present barriers to stabilizing families when they desperately need it most—right away.

In 2018, Winters and Volunteers of America Delaware Valley (VOADV) began partnering through their voluntary reentry program Safe Return. While working together on a small scale, Winters and VOADV’s Senior Vice President Amanda Leese started discussing expanding resources to assist residents who were homeless or at risk of becoming so. They decided to create the IMPACT initiative (Immediate Mobilization of Police Assisted Crisis Teams) under their Navigator Program, which would embed IMPACT specialists within the department 40 hours a week, working side by side with officers.

IMPACT would provide residents with immediate direct services, including housing stabilization, help obtaining identification and transportation, and linkage to medical, mental health, and substance abuse treatment. There would be no cost to the police department.

Leese said they first brought in two full-time IMPACT specialists, then added a third and have plans for a fourth as Pine Hill serves as a regional hub for bordering municipalities. The key, she said, was embedding them right inside police headquarters, which enabled staff to respond in real time.

“We wanted them right there with the officers to work side by side, not in a separate office,” Leese said. Police first stabilize a scene, then IMPACT specialists join the officers, she said. The goal was to be there when a police officer makes contact with the public—during an arrest, in court, at the county jail, inside a hospital, attending a community event, or just stopping to chat with someone on the street. No appointments necessary.

“It’s about being an active member of the community,” Leese said. “It’s not just about being there in a crisis.”

What has enhanced the partnership, Leese said, is that the IMPACT specialists share an online data system with police to communicate essential information in real time which enhances response time.

VOADV has also recently added mobile command centers, emblazoned with VOADV and partnering law enforcement logos. In the first full year, which came during the peak of the pandemic, from November 2019 to November 2020, IMPACT specialists were still able to engage with 258 residents and link 70 percent of them with services they needed.

Even with extraordinary partnerships forming on so many fronts, Winters realized that environmental factors were also affecting the town’s progress.

“Years ago, we would not have been able to understand how addressing vacant homes could impact mental health illness,” Winters said. “However, we now understand that community health and well-being requires a holistic approach.”

The borough’s leadership took an inventory of the more than 500 vacant houses and passed an ordinance to hold the lien holders accountable. They allocated funds for more code enforcement and also addressed park maintenance, enhanced security, and upgrading playground equipment.

“The governing body supports him and provides the funds,” Green, the borough’s mayor, said of Winters’ efforts to help transform Pine Hill. “Nobody can do it by themselves. It has to be a community approach from all facets. It takes everybody.”

It takes a borough.

Juvenile Arrests: And then there Were None

Chuck Warrington, a councilman in Pine Hill and its public safety director, got his start in public service in the borough responding to calls in an ambulance as an EMT.

“I had the opportunity to see so many people slip through the cracks,” said Warrington, a trauma nurse practitioner in Philadelphia. “It is so strange when I look back at where it started, the idea of intervening before someone’s life is affected beyond repair.”

Placing the right people in positions to intervene early, not just arresting them, was the game changer, said Warrington.

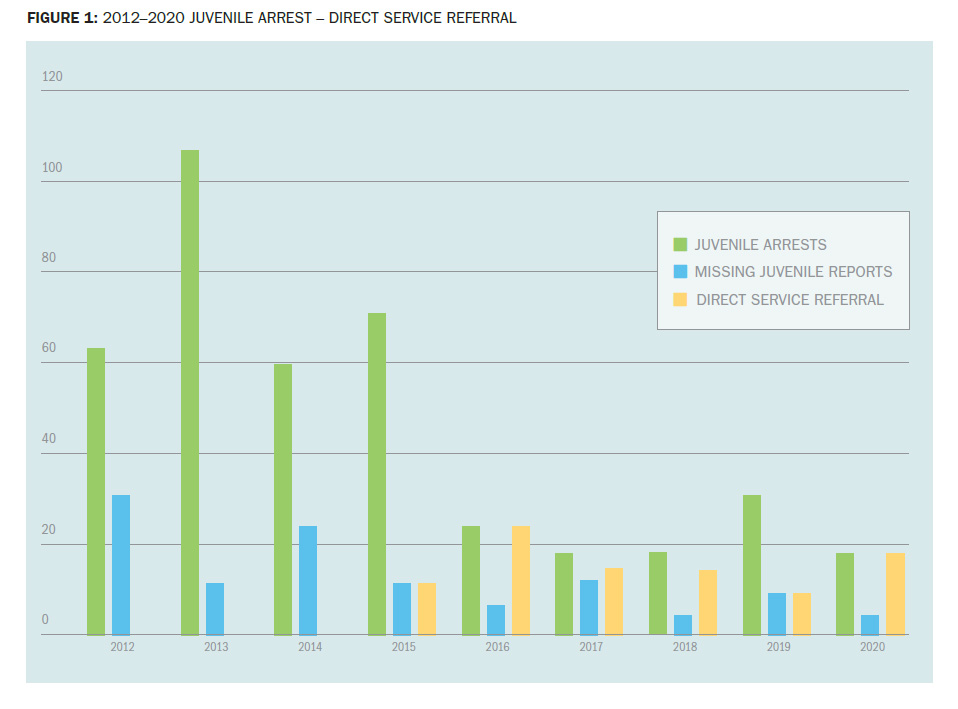

Even Winters, who has been laser-focused on making improvements, was taken aback at just how much of a difference a holistic approach has made in Pine Hill. From 2012 to 2020, juvenile arrests have declined a whopping 83 percent. In 2021 through August, the most recent statistics available, there had been “zero arrests,” Winters said.

The number of at-risk kids running away and reported missing during the same time has dropped substantially, by 83 percent. Adult arrests for serious crimes have also declined by 66 percent.

Progress can be measured in other ways. Because of the success IMPACT has had in Pine Hill, the program has expanded to 12 more police departments in New Jersey, Leese said. Now Project Success is also engaging students in the middle school with their own Game Club using additional funding from the Community Planning and Advocacy Council.

The vacant grocery store is now a vibrant Dollar General store, and a second Dollar General has opened for business in the borough. Other vacant commercial buildings are occupied with local family-owned businesses. Winters and Leese are now helping NCMEC train law enforcement leaders, showing them that engaging the community and partnerships really can make a difference.

Pine Hill has added events for the community, including an annual Christmas parade, July 4th fireworks and a renewed commitment to National Night Out, which celebrates police and community partnerships.

Weldon Lemke, the longtime pastor of Hope Chapel, said he began noticing something profound happening at these community events. Police weren’t an intimidating presence at all, he said. They were hanging with the kids and they clearly all knew one another. “That was pretty remarkable,” he said.

And remember that 13-year-old runaway girl who needed help? Now in her 20s, Winters reached out to her to see if she would agree to meet with him and Leese. They spoke for nearly two hours. He asked what she believed would have happened if her family had received services the first time she ran away.

“I believe I would have went to college and be the nurse I wanted to be,” she told him.

Winters explained that she had made a difference, that she had been a catalyst for extraordinary changes. Because of you, he told her, so many other children are now getting the support that they need. 🛡

Notes:

1Phil Davis, “South Jersey Teacher Indicted on 92 Counts Rrelated to Years of Alleged Child Abuse,” NJ.com, updated January 17, 2019.

2 “How Law Enforcement Agencies in the US,” Google search results.

3U.S. Census Bureau, “Quick Facts: Pine Hill Borough, New Jersey.”

4Morgan Nick Foundation, “Morgan’s Story.”

Please cite as

John F. Clark, “Creating a Culture of Community-Based Change,” Police Chief 88, no. 12 (December 2021): 62–69.