Data has been referred to as the “new oil” by publications as notable as The New York Times, The Economist, and WIRED. Data has been one of the foundational elements of considerable economic growth in the 21st century and has driven innovation and enhanced productivity across a host of industries and professions. But what does this mean for policing? How can public safety leverage data to optimize operations, realize efficiencies, and improve the delivery of police service while being intentional about preserving community trust and working with limited budgets and resources?1

The Availability of Data in Policing Continues to Increase

There was a time, not that long ago, when accessing information for investigations and crime analysis—or to enhance situational awareness in patrol operations—was a challenge. Today, it often seems that police agencies are awash in data but struggle to meaningfully leverage the information to achieve better outcomes. The same can be said for administrative decisions associated with workforce planning and the management of police departments.

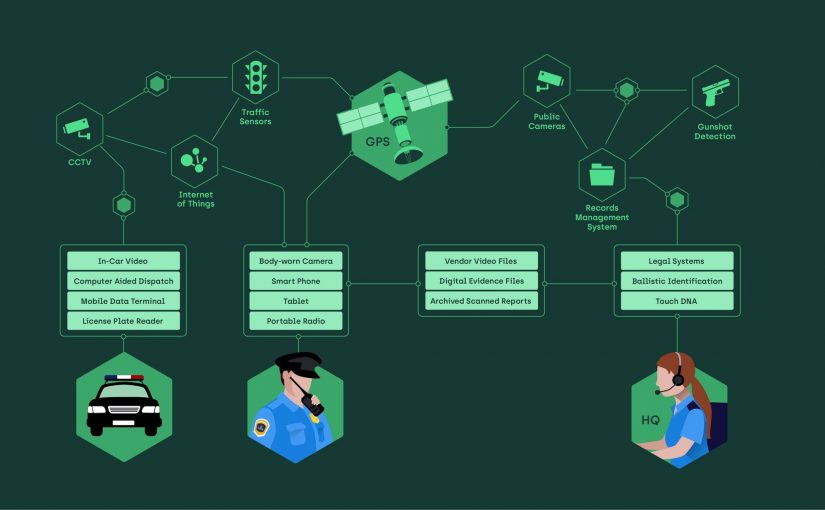

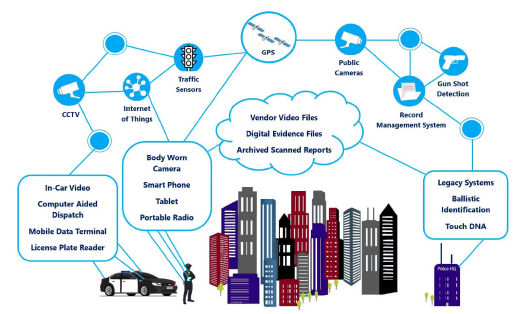

Every year sees an exponential increase in the prevalence of technology available to law enforcement to enhance how they serve their communities, such as sensors like gunshot acoustics and smart video systems that offer movement detection and object tracking—several are even capable of integrating license plate reader technology. Some technology, like electronic record management systems and body-worn cameras, represent solutions implemented by law enforcement agencies themselves. However, many others are the product of the ever-expanding Internet of Things, such as transit system video or consumer alarm sensors integrated with smart home assistants like Google Home or Amazon Alexa.

Every year sees an exponential increase in the prevalence of technology available to law enforcement to enhance how they serve their communities, such as sensors like gunshot acoustics and smart video systems that offer movement detection and object tracking—several are even capable of integrating license plate reader technology. Some technology, like electronic record management systems and body-worn cameras, represent solutions implemented by law enforcement agencies themselves. However, many others are the product of the ever-expanding Internet of Things, such as transit system video or consumer alarm sensors integrated with smart home assistants like Google Home or Amazon Alexa.

Unquestionably, there have never been more sources of information available to law enforcement. The ever-increasing availability of data presents police professionals with both opportunities and challenges. The majority of these systems, even if they are owned and managed by a police department, are disparate systems. This means the information is siloed and typically not available to every stakeholder who needs it in real time. Often, varied systems require signing out of one application to access another—and that presumes the same systems are even available to those working in the field.

Maximizing the Use of Data in Policing

Modern solutions facilitate the integration of data from multiple sources into one technology platform. This allows previously siloed information to be leveraged collectively, enabling line-level users, investigators, analysts, and agency leaders to recognize actionable insights that might otherwise go unnoticed. Additionally, data can be used to bolster trust by providing community stakeholders access to information that is the most relevant to them without having to navigate a complex request process. Several emergent offerings accomplish specific tasks, such as the integration of video, while others offer more comprehensive capabilities to serve many users across the organization. It’s important for agencies to consider what their goals are as they develop a data strategy. Some notable use cases include

- realizing organizational efficiencies,

- maximizing ROI on real-time crime center operations,

- enhancing operational situational awareness,

- increasing investigative capability,

- analyzing and preventing future crime,

- enhancing transparency and bolstering public trust, and

- safeguarding employee health and wellness.

Realizing Organization Efficiencies

CompStat was introduced to policing nearly 30 years ago. Today, most police departments employ some method to develop strategic goals and assess how effective their methods are in meeting those goals. When first introduced, CompStat ushered in a fundamental shift in how law enforcement viewed their mission. Instead of merely responding to calls for service and taking reports after a crime was committed, police began to focus on identifying the root causes of problems and proactively address issues by better managing resources and holding leaders accountable for the outcomes.2

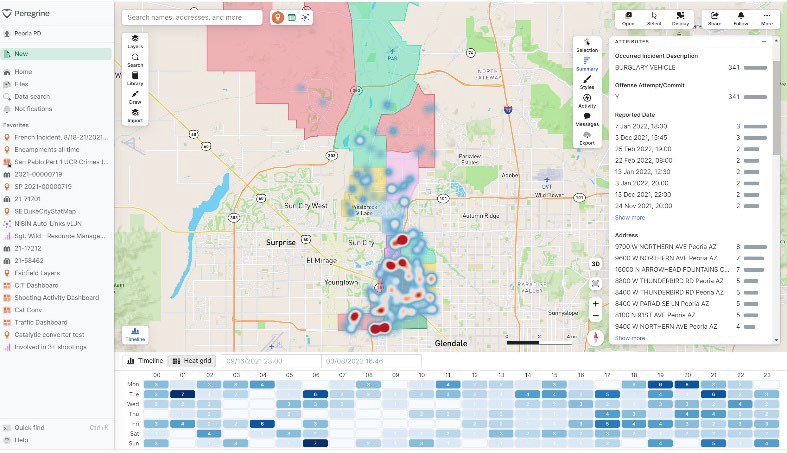

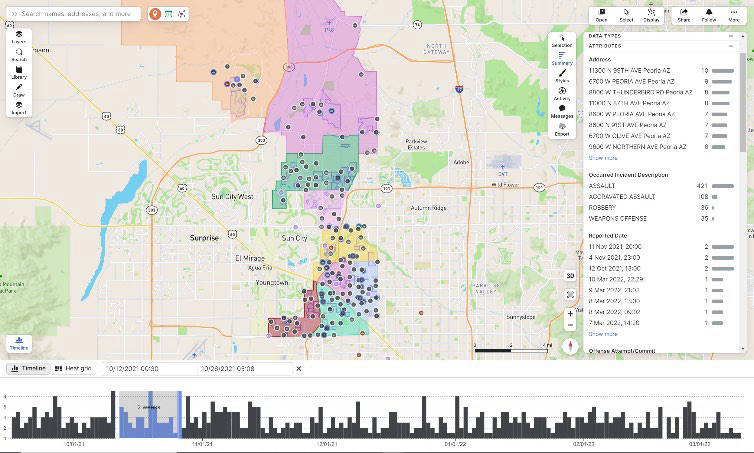

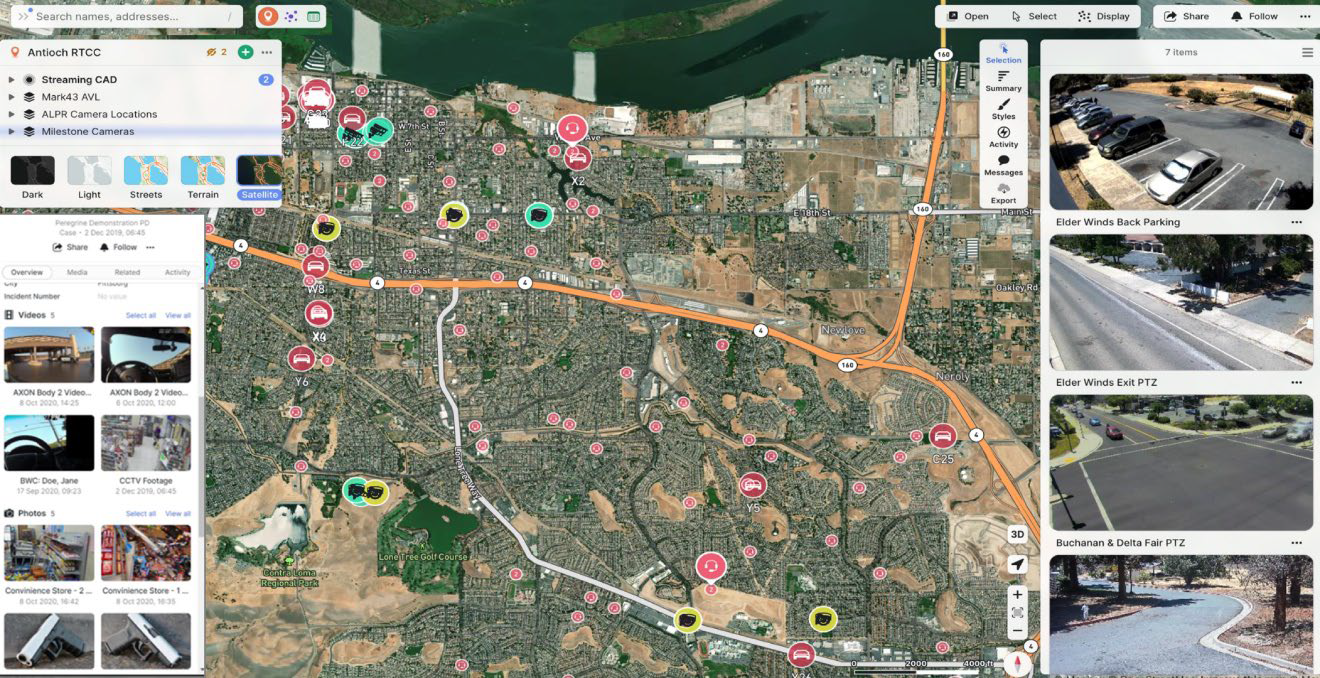

The effectiveness of these programs ranges from model examples of crime suppression strategies to cringe-worthy tales of commanders on the hot seat being grilled about trends that they weren’t even aware of. What is certain is that the effectiveness of any program is predicated on the quality and comprehensiveness of the data being used. Ideally, every stakeholder should have the same access to information, using a tool that is intuitive and that offers easily understood dashboard visualizations, complete with mapping and simple features to navigate between the macro view of a police district and the tactical ground-level information that contributes to statistics.

|

|

When leaders can collectively view up-to-date information on where things are occurring, what is happening, and which resources are available to address those issues, they are far better equipped to optimize police department operations. By analyzing current data on crime rates, response times, and officer performance, police leaders can identify areas where improvements can be made and adjust strategies and methods accordingly. This can help the department work more efficiently, providing better service to the community while maximizing limited resources.

Decisions based on quality data are more defensible than hunches or subjective opinions. Complex information can be presented to the community, elected officials, media, or other stakeholders in a format that is easily understandable. Simplifying data not only allows leaders to make better-informed operational decisions but can help guide more strategic consideration of management issues such as budgeting, staffing, and resource allocation.

Maximizing ROI on Real-Time Crime Centers

Real-time crime centers (RTCC) were once found only in large agencies that possess the robust resources and sufficient personnel to staff them. Many innovative departments are now finding ways to leverage the advantages that an RTCC can offer. RTCCs can provide law enforcement agencies with a valuable tool for enhancing public safety, optimizing their response to incidents, and coordinating resources at the outset of an event or investigation.

An RTCC optimized with the right technology can offer public safety a “common operating picture” (COP) and truly serve as a force multiplier. A COP offers a real-time comprehensive understanding of the environment. It renders a consistent and shareable view of relevant information related to operations by simultaneously visualizing data from various sources such as social media, CCTV footage, reports on file, and other relevant sources.

Data integration leverages the combined synergy of location information with real-time visual representations of the status “on the ground” to provide a clear and intuitive overview of the situation. It can facilitate information sharing, and collaboration among different stakeholders committed to the overarching public safety objectives such as fire, EMS, emergency management, schools, and other public or private partners.

By bringing together data from various sources, an RTCC is better equipped to help public safety partners work collaboratively and share information more easily, reducing the risk of miscommunication or duplication of efforts. These efficiencies can help realize preferred outcomes and even potentially reduce property damage and enhance safety. Furthermore, an RTCC is better equipped to provide investigators with more information sources as well as analytical tools to help them identify suspects, locate evidence, and solve crimes more quickly.

Enhancing Operational Situational Awareness

Many agencies do not have the staffing or resources to maintain an RTCC. However, they can still “democratize their data” to ensure that those who can best leverage the information to affect real-world outcomes are equipped to do so. By utilizing software and the technology that officers already use in the field, like mobile dispatch terminals and smartphones, patrol staff and first-line supervisors can realize many of the benefits of integrated data at scale (historically, accessible only in an office setting) and visualize the information in a manner that is optimized for their work in the field.

Captain (Ret.) Lenny Nerbetski spent 29 years in law enforcement, serving with the New Jersey State Police and then the Albuquerque, New Mexico, Police Department. He served as the executive officer of the New Jersey Regional Operations Intelligence Center and as the commander of the Albuquerque Police Department Real Time Crime Center. He feels that patrol officers are the most visible first-line providers of police service to their communities, but that they’re often the least likely to have access to the technical tools that can enable them to leverage data in ways that actually enhance their capabilities.

Nerbetski noted that most patrol technology serves only a basic essential function, offering body-worn cameras and portable radios as examples. Optimizing a system’s user interface for field work enables patrol officers and their supervisors to identify problem areas, such as traffic, crime, or quality-of-life issues. Without waiting for a report from an analyst or basing their decisions solely on word-of-mouth information, officers can adjust their activity based on impartial insights available to them throughout their shift.

The response to serial crime trends is often saturation patrols or to conduct surveillance. If officers and supervisors can visualize on a map that most residential burglaries in their area of responsibility are occurring primarily on certain days of the week—for example, at single-family dwellings on cul-de-sac streets, where the method of entry is to breach a rear sliding-glass door—then they are far better equipped to address the issue. Strategies informed with data allow departments to take a targeted approach and to work more efficiently. Additionally, the agency can use data to measure the effectiveness of such adjustments and even track response times to optimize dispatch procedures.

During critical incidents, officers and supervisors can develop tactical plans based on comprehensive real-time information. These informed decisions can contribute to better outcomes for both the police and community. Officers are able to work more safely when they have real-time access to information when it is most urgently needed. Too frequently, after-action reports pertaining to tragic outcomes involving fallen officers reveal critical information that was either never relayed to the responding units or was known within the agency somewhere but not accessible at the time of the event.

Increasing Investigative Capabilities

Devices such as smartphones, tablets, wearable technology, interconnected household devices, and other technology that store data have already been shown to hold evidence that is critical to solving crime. For instance, a murdered woman’s Fitbit log and Facebook activity offered key evidence leading to the arrest of her husband who alleged she had been killed by a home intruder. During a spree of hate crimes in Texas, four defendants used a dating app to lure and brutally victimize at least nine people who were targeted for their sexual orientation.3

Seasoned investigators know that gathering information at the outset of a case can be a dynamic and fluid process. Often, key pieces of information are incomplete, like partial license plates, nicknames, or a pre-paid phone number with no subscriber information available. When a detective serves a search warrant for call detail records or geo-fence data, the returned information from the provider isn’t formatted in a manner that offers obvious insights. Unsearchable data or worse, data that exist but aren’t even known about, offer no utility.

Archived documents such as handwritten reports and citations or notes stored in formats like PDFs can often contain valuable information, especially in cold cases. Optical character recognition is the same technology that allows license plate readers to convert images of a plate into a digitally searchable format. This technology is used with modern software solutions capable of normalizing historic records and making the information contained in them readily searchable.

Support from trained analysts using sophisticated technical tools is often available only for certain priority cases, if available at all. Using a technology solution that facilitates searching across datasets allows detectives to piece together fragments of information and fill in critical information gaps on their own. As investigators uncover new insights they can explore relevant theories, develop new leads, and advance investigations more quickly and with greater precision.

Analyzing and Preventing Future Crime

Most community members who live in areas where violent crime is prevalent are law abiding and have often been victimized themselves. Absent evidence-based insights as to the root causes of issues, crime prevention measures can seemingly be directed at an entire community, eroding the perceived legitimacy of a police department’s efforts.4

Traditional hot spot policing based on single-dimensional information, such as the location of prior arrests, has been scrutinized for contributing to the over-policing of marginalized communities. When community members see the police as an occupying force, as opposed to a collaborative partner with shared goals, it undermines the trust that the community has in the intentions of an agency.5

The Danish National Police are regarded as leaders in the area of intelligence-led policing. Their model is both thoughtful and intentional. By prioritizing the ongoing active interpretation of the criminal environment, they strive to offer leaders an objective decision-making framework. This model still focuses on hot spots but also incorporates more holistic data points related to victimology, prolific offenders, and organized criminal groups.6

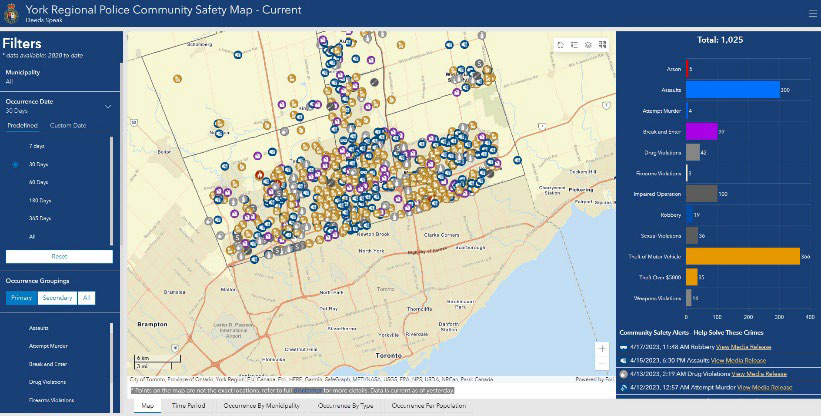

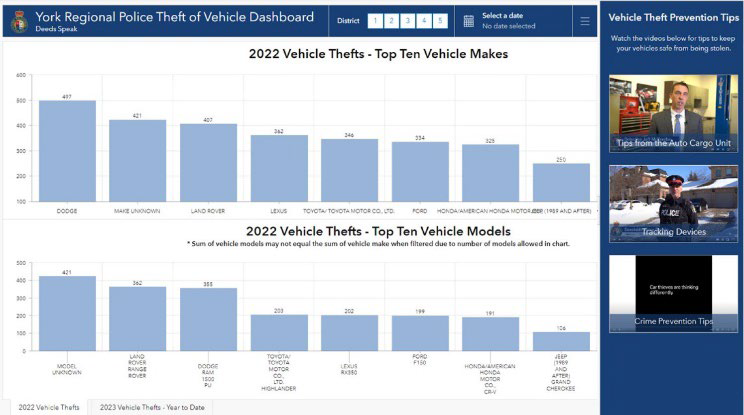

By sharing data with the community, law enforcement agencies can gain a more comprehensive understanding of crime and adopt mutually agreed-upon goals to proactively intervene in a manner that maintains credibility in the eyes of the community. The effectiveness of any data program is predicated on the comprehensiveness of the data used, but its utility hinges on the training and skill of analysts and the quality of the technical tools that they have to work with.

Enhancing Transparency and Preserving Public Trust

Gregory Stanisci serves as the manager of Business Intelligence and Data Analytics for the York Regional Police in Canada. In February 2019, he addressed a room of law enforcement leaders at a meeting hosted by the Canadian Association of Chiefs of Police. Stanisci articulated his vision for the use of police data in a different way. He saw the traditional model of creating reports to be reviewed by leaders after the fact as antiquated. He was already pioneering innovative ways of helping line-level officers leverage data for real-time decisions.

Recently with the support of his agency, Stanisci and his team launched a new Community Safety Data Portal. The solution was developed with the philosophy that “community safety is a shared responsibility.” The agency not only provides the data to community members via this portal—but also presents the information in concert with crime prevention material so the public can directly engage in efforts to address issues specific to their own communities. The public can better understand the crime trends that are affecting their communities and recognize how to help keep their own families and neighbors safe. Furthermore, they have an informed perspective as to what the police are doing to address crime in their community.7

|

|

Safeguarding Employee Health and Wellness

The York Regional Police are leveraging data in other cutting-edge ways that are unrelated to conventional police operations and agency management. Stanisci and his team are working to develop an employee wellness analytics platform. By creating dashboards to track customized data sets that had not previously existed, they are using business intelligence tools to safeguard the mental health of their employees.

Assisted by psychologists, they are developing a system to leverage data to support the wellness of both their sworn and civilian members. They created a “tiering system” to record the intensity of the calls for service that their employees are exposed to. By capturing the severity of a single event or the cumulative effects from multiple critical incidents, they are striving to automate the identification of employees who might benefit from additional support services. Ideally, they hope the solution will aid in identifying members who may not identify themselves or perhaps may not even recognize their own level of vulnerability from chronic exposure to traumatic incidents.8

Police Data Is Different

One cannot discuss police data without acknowledging the unique nature of the information law enforcement holds. Police agencies are custodians of personally identifiable information (PII) that must be safeguarded. However, information that law enforcement possesses is often uniquely sensitive, from the embarrassing private details of feuds between significant others, to the traumatic and deeply personal details of a sex crime.

In the normal course of business, police departments collect intimate details of people’s lives related to situations when they are perhaps most vulnerable. Information security and data privacy are paramount for reasons far beyond just safeguarding PII. Law enforcement must effectively safeguard people’s deepest secrets if they are to maintain their trust.9

Law enforcement leaders do not need to be technical experts to responsibly leverage data, but they must be cognizant of cybersecurity. It needs to be baked into every element of a technical solution. Cloud-based storage options were once viewed by many as inappropriate for local government purposes. Increasingly, the cloud has become a more cost-effective option, allowing agencies to leverage both the enhanced security features for data storage and more robust computing capability for complex processes like analytics.10

When it comes to data programs, every member of the organization must have a role in maintaining the security and integrity of an agency’s systems. To safeguard data, police departments should ensure they employ basic information security best practices:11

- Limit access to sensitive data to only authorized personnel and ensure that each user has a unique login and password. Implement multifactor authentication for added security.

- Use encryption to protect data both in transit and at rest. Ensure that all communication protocols are secure and that sensitive data are not transmitted over unsecured networks.

- Regularly patch and update software to prevent known vulnerabilities from being exploited.

- Perform regular vulnerability assessments and penetration testing.

- Use network segmentation to prevent attackers from gaining access to critical systems or sensitive data if they manage to penetrate the perimeter.

- Establish an incident response plan for responding to cybersecurity incidents.

- Train employees on cybersecurity best practices and foster a culture of vigilance.

What to Look For in Solutions and Partners

Data integration solutions are not new, but their utility has only recently been optimized for public safety. In the age of ever-expanding data sources, technology that may have been once viewed as “nice to have” is now essential. The advantage that these solutions can offer with respect to budget and resources is the opportunity to maximize existing systems, like CAD/RMS, while potentially sunsetting antiquated stand-alone programs that create more challenges than they solve.

When choosing vendors to work with, it’s imperative to assess technology products and choose partners who prioritize information security and who are committed to the same ethical outcomes as the agency. Additionally, seek out vendors who offer ongoing professional services such as training tailored to the role of individual users and who agree to collaborate with the agency to refine system features as needed or based on an agreed-upon cadence. General features and capabilities to consider include the following:

User Experience Features

- Integration of all data sources into a single platform is accessible via a secure, single sign-on.

- Full stack solution enables data ingestion and normalization that offer a seamless experience for the end-user where they are able to intuitively toggle between different data sources.

- Views and functionality are configured for those in the field as well as those in office settings.

- Customizable dashboards are tailored for users based on their roles.

- Interactive mapping views and functionality increase awareness.

- Cross-case searching capability helps to surface associations across multiple data sources.

- Real-time synchronization optimizes collaboration and informed decision-making.

- Watchlists and automated alerts notify analysts, detectives, and officers when somebody else has interacted with information relevant to their cases.

Technical Features

- Interoperability is vendor agnostic when it comes to the data sources that a system can ingest and normalize.

- Audit logs preserve transparency and accountability by recording the access or modification of records.

- Unification of data isn’t just accessible but is rendered in a manner that is optimized for the purpose of each user.

- The solution can handle structured and unstructured data , including legacy reports, handwritten documents, etc.

- The system is scalable for use across the agency, as well as other government or public safety partners.

Security Features

- Data are hosted in a secure, CJIS-compliant environment.

- The system offers automated security patching and design of countermeasures to vulnerabilities.

- It Incorporates monitoring to collect and restrict unauthorized intrusion attempts.

- The system runs intrusion detection to determine possible network-based cyber-attacks.

Conclusions and Recommendations

Ethically leveraging data using proven technical solutions can help law enforcement agencies to better address crime, improve efficiencies, and build trust with their communities. Modernizing a police department’s capabilities does not have to be at odds with preserving civil liberties. Crafting sound policies and thoughtfully engaging with the communities they serve can help police departments identify data practices that equitably serve all stakeholders.

Technology doesn’t replace trained professionals; it helps good people do their best work. Police professionals can leverage innovative solutions while simultaneously striving to preserve public trust. As Steve Jobs famously declared, “It’s not a faith in technology. It’s faith in people.”12 d

Notes:

1Gabriel Dance, Michael LaForgia, and Nicholas Confessore, “As Facebook Raised a Privacy Wall, It Carved an Opening for Tech Giants,” New York Times, December 18, 2018; “The World’s Most Valuable Resource Is No Longer Oil, But Data,” Leaders, The Economist, May 6, 2017; Joris Toonders, “Data Is the New Oil of the Digital Economy,” Insights, WIRED (July 2014).

2Police Executive Research Forum (PERF) and the Bureau of Justice Administration, CompStat: Its Origins, Evolution, and Future in Law Enforcement Agencies (Washington, DC: PERF, 2013), vii.

3Amanda Watts, “Cops Use Murdered Woman’s Fitbit to Charge Her Husband,” CNN, April 26, 2017; Oliveira, Nelson, “Another Texas Man Admits Using Grindr to Target Gay Men, Beat Them Up and Rob Them,” New York Daily News, June 4, 2021.

4Lenny Nerbetski, “Peregrine 101: Improving Field Operations for Officers and Their Community,” Peregrine Blog, April 11, 2023.

5Alice Norga, “4 Benefits and 4 Drawbacks of Predictive Policing,” Liberties, July 12, 2021.

6Jakob Lindergård-Bentzen, “Preventing, Disrupting & Deterring Crime with Data: Intelligence-Led Policing in the Special Crime Unit in Denmark,” Police Chief 90, no. 4 (April 2023): 48–52.

7Jim Love, “Data Driven Policing in York Region – Greg Stanisci, Manager of BI & Data Analytics,” IT World Canada, April 28, 2022.:

8Love, “Data Driven Policing in York Region.”

9Christian Quinn, “A Delicate Balance,” Police Professional (October 2022): 25.

10Christian Quinn et al., “The Biggest Technology Challenges Facing Police Leaders,” Police1.com, March 22, 2022.

11Christian Quinn, “The Emerging Cyberthreat: Cybersecurity for Law Enforcement,” Police Chief Online, December 12, 2018.

12Jeff Goodell, “Steve Jobs in 1994: The Rolling Stone Interview,” Rolling Stone, January 17, 2011.

Please cite as

Christian Quinn, “Data Rich but Information Poor? Not Anymore: Police Are Able to Leverage Data Like Never Before,” Police Chief Online, September 6, 2023.