The Call

“911, What’s the address of the emergency?”

The dispatcher barely discerns a faint inaudible whisper.

“Hello, Hello, 911, What’s the address of the emergency?”

A hushed and tenuous voice replies, “There’s someone breaking into my house.”

The Dispatch

A report of a burglary in progress presents a serious and potentially dangerous situation. This possibility of danger may affect the human performance capacities of first responders because it limits their breadth of attention. Officers who fear for their safety may not have the needed cognitive resources to adjust their response to a new reality if the initial dispatch information turns out to be incorrect.1 What if this call is not a burglary in progress at all? What if the individual entering the home is an autistic teenager who is prone to wandering? Police leaders must understand that when their officers respond to these types of perilous situations, they may be in a state of increased arousal that will focus their attention narrowly on those aspects of the situation officers consider most important.2 Research has found that greater reliance is given to information that is available as opposed to other possibilities that remain unknown.3 Altering a response after priming presents a significant challenge, and—if officers are unsuccessful at adapting to new information—they risk a possibility of a catastrophic outcome.4

The preceding situation is based upon a real call for service in the Town of Colonie, New York. A safe outcome was preordained before officers ever arrived, through an enhanced use of their vulnerable person registry.

Vulnerable Person Registries

Vulnerable person registries have been promoted by both the International Association of Chiefs of Police and the FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin.5 The primary focus for the use of these registries in the policing community has been on the maturing population with Alzheimer’s Disease and, to a lesser extent, on individuals with special needs, such as autism. The Town of Colonie made three key, budget-friendly enhancements to these programs that were used in concert with the agency’s existing CAD and GIS systems.

Enhancement 1: A Direct Focus on Persons with Mental Illness

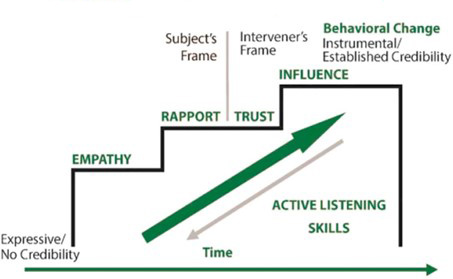

Police are often the only first responders to people with mental illness (PMI) who are in acute distress.6 When people are in crisis, emotions tend to control actions rather than reason. Successfully returning the subject to a rational state of mind requires trust.7 Active listening skills form the bedrock of successful crisis intervention and act as the gateway toward persuading a person in crisis to trust the responder and move toward a successful behavioral change.8 Skilled crisis communicators are well versed in the Behavioral Influence Stairway Model (BISM) shown in Figure 1.

| Figure 1. Behavioral Influence Stairway Model |

|

However, walking up this stairway takes time. The Town of Colonie’s leadership wondered if there was a way to utilize the vulnerable person registry system to aid officers when seconds count. They did not want officers to just walk up the stairway, they wanted officers to be able to bound two or three risers at a time during crisis interventions. Would safer outcomes result if the police knew both the triggers and calming methods of the person in acute distress?

This exploration found that such an enhancement tends to shorten the amount of time required to demonstrate empathy and build trust. Responding officers are not starting from zero; they now enter crisis intervention scenes equipped with critical rapport building information.

Community Engagement

Now more than ever, today’s societies demand that organizations must commit to meaningfully engage with groups that are affected by police activities.9 The public is calling on the police to partner with and gain the approval of civil societal organizations for effective engagement.10 Engagement means more than an “informational” session with the public; it implies that the police will consult, involve, and collaborate with the public.11

The National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) New York State was a primary stakeholder on the Town of Colonie’s enhancement project. Through this partnership, NAMI both supported and promoted its implementation with their members, providing a needed “stamp of approval” to gain the trust of a hesitant population.

In conjunction with NAMI, the Town of Colonie developed a questionnaire for caretakers and guardians focusing on triggers and calming methods that will be helpful for first responder encounters. The questionnaire development favored open-ended questions over multiple choice. This format meant the caretakers and guardians entering information would be able to focus on what they felt was the most important information to assist in communicating with their loved ones and were also in control of the amount of personal information they shared. For ease of access, this questionnaire was posted online, and responses were submitted electronically. After a verification process, the information entered by the caretaker is converted into a PDF document and relayed to both communicators and patrol officers for situational awareness.

Enhancement 2: CAD Integration

The next logical challenge was converting the critical information collected by the questionnaire into actionable intelligence for the first responders and communicators. In the past, similar information may have been distributed at shift briefings in the hope of informing a majority of the officers who may interact with the individual. Without personal experience to reinforce those neural pathways, however, this valuable information would often be forgotten by most personnel within weeks of the briefing. In order to avoid this pitfall, the police department took a novel approach using a current system.

Instead of relying upon individual officer memory retention, the police department integrated the vulnerable person registry information into a system the personnel use every day—computer-aided dispatch or CAD. Vulnerable person information submitted via the questionnaire was added to the BOLO person and BOLO location files. As a result, any call dispatched to the residence of a person on the registry will alert the dispatcher and the responding officer to the vital information contained on the registry. Furthermore, if the subject’s name is queried during the course of a response, the BOLO Person information would alert users to investigate the content, which includes all of the triggers and calming methods supplied by the caretaker as well as a photograph of the vulnerable person.

Enhancement 3: GIS Integration

The integration of these data into the CAD system satisfied the initial intended purpose of assisting officers at known locations or when interacting with known individuals. Still, this experience informed the police department that it could do more. Some of the most vulnerable individuals encountered in the jurisdiction are nonverbal and prone to wandering. As a result of the latter, many police interactions with these consumers are not at their residences and are reported by individuals who are not familiar with their identities.

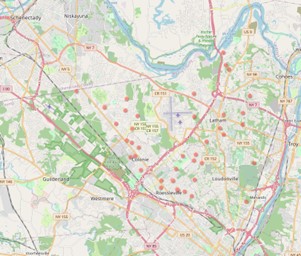

| Figure 2. GIS Map |

|

By partnering with the agency’s geographic information system (GIS) counterparts, the locations of vulnerable individuals were plotted on a map. Using the CAD system, the “Handle with Care”’ layer was added to the dispatchers’ maps and those in the patrol officers’ vehicles. Interactive map features give users the ability to drill down on each location pin and retrieve the full “Handle with Care” questionnaire for the individual at that location. The visual reminder of vulnerable persons living in the area provides enhanced situational awareness for call takers, dispatchers, and first responders. The end result is greater flexibility for the end user to interact with the data.

Burglary in Progress

Circling back to the original burglary in progress call, an astute dispatcher recognized the Vulnerable Person “pin” on the GIS map. The document was opened and revealed that an autistic teenager, prone to wandering, lived just four houses away. The teen’s mother was reached on the telephone, and she discovered her son had snuck out through a bedroom window. Officers were advised of the updated information and were now prepared for a second possibility—that the “burglar” may not be a burglar at all. Officers were able to view the teens’ picture en route and they arrived armed not only with service equipment but with knowledge of calming methods to use and triggers to avoid.

The intruder was indeed the teen. A safe resolution was achieved, and a potential tragedy was averted.

Conclusion

Wise executives will follow the U.S. Department of Justice Civil Rights Division recommendations for police agencies to establish community health collaborations and have robust systems in place for handling encounters with those with mental illness or disabilities.12

Policing in the 21st century demands harm-focused, intelligence-led approaches to public safety. Trust and confidence in police do not stem solely from tackling crime. Modern police executives should be aware that the public wants officers to deliver services that address harm and community safety and reassurance in a structure that instills confidence and is procedurally just.13

Integration of vulnerable person registries into an agency’s existing CAD system is a great way to make deposits in the bank of community trust while also improving the safety of officers and vulnerable community members.

Notes:

1Paul L. Taylor, personal communication, March 3, 2023.

2Alan D. Baddeley, ” Selective Attention and Performance in Dangerous Environments,” Journal of Human Performance in Extreme Environments 5, no. 1 (October 2000): art. 9.

3Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman, “Availability: A Heuristic for Judging Frequency and Probability,” Cognitive Psychology 5, no. 2 (September 1973): 207–232.

4Paul L. Taylor, “Dispatch Priming and the Police Decision to Use Deadly Force,” Police Quarterly 23, no. 3 ( September 2020): 311–332.

5International Association of Chiefs of Police (IACP), A Guide to Law Enforcement on Voluntary Registry Programs for Vulnerable Populations (Alexandria, VA: IACP, 2017); Keith Stambaugh, “Registries for Persons Prone to Wandering,” Perspectives, Law Enforcement Bulletin, February 9, 2023.

6H. Richard Lamb, Linda E. Weinberger, and Walter J. DeCuir, “The Police and Mental Health,” Psychiatric Services 53, no. 10 (October 2002): 1266–1271.

7Gregory M. Vecchi et al., “Negotiating in the Skies of Hong Kong: The Efficacy of the Behavioral Influence Stairway Model (BISM) in Suicidal Crisis Situations,” Aggression and Violent Behavior 48 (September–October 2019): 230–239.

8Gregory M. Vecchi, Vincent B. Van Hasselt, and Stephen J. Romano, “Crisis (Hostage) Negotiation: Current Strategies and Issues in High-Risk Conflict Resolution,” Aggression and Violent Behavior 10, no. 5 (July–August 2005): 533–551.

9Neil Jeffery, Stakeholder Engagement: A Road Map to Meaningful Engagement, Doughty Centre, How to Do Corporate Responsibility series (Wharley End, UK: Doughty Centre, Cranfield School of Management, 2009).

10Ian Loader, “In Search of Civic Policing: Recasting the ‘Peelian’ Principles,” Criminal Law and Philosophy 10, no. 3 (September 2016): 427–440.

11IAP2, Public Participation Pillars.

12U.S. Department of Justice, Civil Rights Division, The Civil Rights Division’s Pattern and Practice Police Reform Work: 1994–Present (2017).

13Jerry Ratcliffe, Reducing Crime: A Companion for Police Leaders (New York, NY: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2019).

Please cite as

James J. Gerace and Todd H. Weiss, “Enhancing the Capabilities of Vulnerable Person Registries: When CAD and Compassion Converge,” Police Chief Online May 29, 2024.