September 11, 2001, began as a beautiful, crisp fall day without a cloud in the deep blue sky. Children were on their way to their first day of school, a local election was underway, and individuals were going about their daily routines. In what seemed to be the blink of an eye, people’s lives changed dramatically. The naïve belief that terrorism happened in other countries was replaced with the grim reality that the United States was vulnerable. The 9/11 attacks were a wake-up call.

The terrorist attacks on September 11 transformed the course of U.S. history, and sent shock waves that reverberated globally, changing how the public and responders view the safety and security of their communities and the world. Sadly, 2,977 innocent men, women, and children were killed at the World Trade Center in New York City; the Pentagon in Arlington, Virginia; and in Shanksville, Pennsylvania, where a plane crashed into an open field.

The terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001, drastically changed the lives of the nearly 3,000 families, from 93 countries, whose loved ones perished that day.

In the days following 9/11, a devastated country mobilized. Families filed missing persons reports and frantically searched for information about their loved ones. The smoldering World Trade Center site was the largest crime scene in the history of the United States, and therefore the largest recovery effort the country has ever undertaken. The New York City Chief Medical Examiner Dr. Charles Hirsch and his team had the monumental task of collecting DNA samples from the families of victims and missing persons, as recovery workers were simultaneously gathering human remains at the World Trade Center site. Families suspecting the inevitable, held memorial services without their loved ones’ remains or bodies to bury. The country and the world were on high alert, as law enforcement, counterterrorism experts, and government officials worked overtime to prevent another attack.

Family Assistance Centers (FACs) were set up in New York City; New Jersey; Washington, DC; Shanksville, Pennsylvania; Boston, Massachusetts; and other areas. Families from around the world flooded into the centers seeking information about their loved ones. They completed endless forms, filed missing persons reports, and provided DNA samples and personal items of their loved ones. Each FAC was a central location that provided information and support and a safe haven where families could connect with one another—many sharing photographs and missing person posters. However, many families living around the United States and in 93 countries around the globe were unable to visit the FACs due to their geographical distance. Consequently, they had challenges accessing information and accounting for their loved ones. Many also had language barriers, further complicating their access to information.

Once the FACs closed, hundreds of organizations stepped forward to provide short-term services. However, without a central coordination of information and delivery of services, organizations often duplicated efforts, and families were frustrated by repeatedly being asked for identifying information.

At the time, neither the government nor the organizations providing services recognized that the 9/11 community would have long-term, ongoing needs in the years to come. Funding ran out and services ended prematurely.

The tragedy shined a spotlight on the inadequacies of the government and federal agencies to prevent a terrorist attack due to systemic failures within and among agencies to communicate. Similarly, it demonstrated that the United States was unprepared to effectively respond to a tragedy of this magnitude that affected families domestically and abroad. It also brought to light that tragedies often have international consequences that require cross-border cooperation, both in preventing and responding to the event.

Shortly after 9/11, Mary Fetchet and the late Beverly Eckert established Voices of September 11th, now known as Voices Center for Resilience (VOICES), to provide families with information and support and advocate on their behalf regarding the myriad issues they faced at a time of grieving. VOICES held meetings with families to assess their needs, and informal coalitions of family advocates began meeting with elected officials in New York City and Washington, DC.

VOICES’ advocacy efforts were focused on ensuring that families were informed, represented, and involved in the decision-making process regarding issues that impacted them. Some of the organization’s immediate priorities were focused on streamlining the process concerning the notification of family members regarding remains; ensuring an appropriate memorial was built at the World Trade Center site; and advocating for a full investigation into the systemic government failures that led to the attack.

In the immediate aftermath of the attacks, the New York City Office of the Chief Medical Examiner (OCME) began the monumental task of collecting and identifying human remains. More than 22,000 human remains of 2,753 victims were collected during the recovery efforts at the World Trade Center site.1 Various agencies were tasked with collecting DNA samples from families who were geographically dispersed. Once the OCME made an identification, they relied on local law enforcement officers to notify the family. Often, the officers were not properly trained, and families were unprepared when an officer arrived at their front door. The return of body parts was unprecedented, and funeral directors who processed human remains often had to plan multiple burials for the same person. Families wanted more control over how and when they were notified, so VOICES worked with OCME to streamline the notification process, allowing families to determine if, how, and when they were notified of the identification of their loved ones’ remains.

As the recovery effort continued, the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation (LMDC) was formed by New York Governor George Pataki to help plan and coordinate the rebuilding and revitalization of Lower Manhattan and to oversee the creation of the memorial. Although the attack occurred on one of the most valuable pieces of commercial real estate, families of victims considered the place where their loved ones died to be sacred ground. Advocates, including the author, joined the LMDC Family Advisory Committee to represent the families’ views during the planning process and to ensure a 9/11 memorial was built to honor the 2,977 victims so that future generations understood the losses suffered and the magnitude of the event. It was a long and arduous process, yet the families’ involvement helped shape the memorial.

The September 11 terrorist attacks were the deadliest loss of life in the history of the United States, and many believed the tragedy warranted a full investigation into what led up to and contributed to the failure of the government to prevent the attacks.

Advocacy efforts for the creation of a 9/11 independent commission began in June 2002, when 9/11 families held a rally in Washington, DC. It was clear from news reports that failures within and among government agencies contributed to the success of the terrorists in attacking the United States, leading to the deaths of thousands of innocent people. In response to Congress’s resistance, 12 determined family members formed the 9/11 Family Steering Committee, which made endless trips to Washington, DC. The committee held rallies and candlelight vigils, made phone calls and faxed letters, and visited all 100 U.S. senators and 435 representatives. The 9/11 Family Steering Committee had ongoing negotiations with the White House, and the members became subject matter experts on intelligence reform and testified before Congress. The 9/11 Commission was established in late 2002, and New Jersey Governor Tom Kean and U.S. Congressman Lee Hamilton cochaired the bipartisan investigation. Their final report resulted in recommendations that led to sweeping intelligence reforms designed to guard against future attacks. Beyond the 9/11 report, they spent years ensuring their recommendations were legislated and funded, and they continue monitoring its effectiveness. As a result, U.S. communities are safer today.

Advocacy efforts for the creation of a 9/11 independent commission began in June 2002, when 9/11 families held a rally in Washington, DC. It was clear from news reports that failures within and among government agencies contributed to the success of the terrorists in attacking the United States, leading to the deaths of thousands of innocent people. In response to Congress’s resistance, 12 determined family members formed the 9/11 Family Steering Committee, which made endless trips to Washington, DC. The committee held rallies and candlelight vigils, made phone calls and faxed letters, and visited all 100 U.S. senators and 435 representatives. The 9/11 Family Steering Committee had ongoing negotiations with the White House, and the members became subject matter experts on intelligence reform and testified before Congress. The 9/11 Commission was established in late 2002, and New Jersey Governor Tom Kean and U.S. Congressman Lee Hamilton cochaired the bipartisan investigation. Their final report resulted in recommendations that led to sweeping intelligence reforms designed to guard against future attacks. Beyond the 9/11 report, they spent years ensuring their recommendations were legislated and funded, and they continue monitoring its effectiveness. As a result, U.S. communities are safer today.

Many of the key issues that impact the recovery of victims and families were drawn out, such as compensation, the building of a memorial, a trial, holding perpetrators accountable, and the identification of remains. Still today, after nearly two decades, many of these issues are unresolved.

Many of the key issues that impact the recovery of victims and families were drawn out, such as compensation, the building of a memorial, a trial, holding perpetrators accountable, and the identification of remains. Still today, after nearly two decades, many of these issues are unresolved.

The 9/11 Memorial Plaza was dedicated on September 11, 2011, and the 9/11 Memorial on May 15, 2014. Many of the components the families advocated for were incorporated into what is now an inspiring 9/11 Memorial Museum.

These included the use of water to drown out the sound of the city; preservation of the footprints of the twin towers; the victims’ names inscribed around the pools of water; the survivor staircase where many escaped; the unidentified remains, located between the north and south towers; and the unfettered story about 9/11.

Most importantly, families wanted the faces, names, and the stories of the 2,977 victims to be told so that future generations would always remember. To that end, the Voices of September 11th Living Memorial Project created a digital archive honoring the 2,977 lives lost and documenting their stories through photographs and personal mementos contributed by their families. Today, the Living Memorial is an extensive online collection of more than 87,000 photographs, and a copy of the archive is a core component of the In-Memoriam exhibit at the 9/11 Memorial Museum.

Nearly 20 years later, the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner still has more than 7,000 unidentified remains in their possession, and more than 1,100 families have never been notified of their loved ones’ remains. The dedicated staff at the OCME has made the long-term commitment to use advanced DNA technology until all remains are identified.

Nearly 20 years later, the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner still has more than 7,000 unidentified remains in their possession, and more than 1,100 families have never been notified of their loved ones’ remains. The dedicated staff at the OCME has made the long-term commitment to use advanced DNA technology until all remains are identified.

The terrorist trials in Guantanamo are slow moving and ongoing. Lawyers are still seeking documents from the federal government that are likely to hold the perpetrators accountable.

In the aftermath of 9/11, there was little understanding that victims of trauma have long-term needs. VOICES continues to hear from members of the 9/11 community asking for assistance to connect them with resources and mental health care. In addition, in recent years, advocates recognizing intergenerational consequences, such as the increase in the need for mental health treatment among the now young adults, who suffered a loss that day as children.

The effects of 9/11 are also still felt among the 90,000 responders and 400,000 survivors who were exposed to toxic contaminants and emotionally stressful conditions in Lower Manhattan on 9/11 and in the days and months following while working in the recovery effort.2

After years of advocacy efforts by first responders, the World Trade Center Health Program was legislated to provide medical and mental health treatment. Today, nearly 83,000 responders and survivors are in treatment for life-threatening illnesses and serious medical conditions. Over 4,100 have died from the 9/11-related illnesses they contracted.3

Lessons Learned

So, what are the lessons learned from 9/11 and what progress has been made? Following a tragedy, victims, survivors, and responders need a central hub that provides information and support. Long-term services and access to mental health care are imperative, as is the coordination of resources within and among agencies. The circle of impact extends beyond the victims’ families. The needs of survivors, witnesses, responders, and the community at large should all be considered. Preplanning a community response is essential for organizations and agencies to have the proper training and to establish an effective and immediate response. Many tragedies have international consequences that require cross-border coordination.

Over the course of 20 years, there has been a transformational shift in the focus toward a victim-centered approach. VOICES has had the pleasure of working with individuals and organizations in law enforcement, counterterrorism, and victim services, in the United States and abroad, such as International Association of Chiefs of Police, Leadership in Counterterrorism Alumni Association, and International Network Supporting Victims of Terrorism and Mass Violence (INVICTM), to mention a few. Their dedication and commitment to public service, public safety, and the greater good of our communities and the world is inspiring, and VOICES looks forward to the continued work together.

The Victim-Centered Approach

Mass victimization incidents such as terror attacks and mass shootings all carry the potential for significant trauma to a wide circle of people. Great work has been done and is currently being undertaken by governments, first responders, victim service agencies, and community stakeholders to prepare for and respond to these types of incidents; however, it must also be asked whether enough is being done to support victims, survivors, families, first responders, and all those who have been impacted by these events.

Mass casualty incidents pose significant challenges to responding agencies to provide appropriate assistance efficiently and effectively to victims, survivors, families, first responders, and all those impacted. The key to addressing these challenges is a victim-centered approach, in which victims’ experiences and voices inform preplanning and response strategies. The earlier the appropriate intervention to help victims address the challenges they face, the more resilient they can be. Applying a victim-centered approach to the development of a counterterrorism/mass violence response strategy will ultimately help to achieve the objective of enhancing the safety, well-being, and resiliency of those who have been impacted.

Thoughtfully preplanned processes, grounded in the evidence-informed models, tools, and lessons learned from the local, national, and international context and developed in collaboration with key partners, will help to ensure victims’ rights are protected and the necessary protocols are in place at the time they are needed.

Incorporating Victims’ Issues into Planning and Response Strategies

Why is it necessary to employ a victim-centered approach? As per the FBI:

The quality of the overall response to mass fatality incidents (whether caused by criminal or accidental events) will, in large part, be judged by the manner in which victims and families and all those impacted are supported and treated.4

It is a critical point in time for policing, a time when significant changes are necessary to maintain public confidence, ensure integrity and excellence in service to the public, and build healthy and safe communities. Now, more than ever, law enforcement agencies (LEAs) need to work within collaborative frameworks and develop response plans that recognize the importance of addressing all aspects of the criminal justice continuum—starting with prevention, through the time of the crime, to criminal justice proceedings, and beyond.

A victim-centered approach forms part of a human rights approach to policing, founded upon the fundamental principles of respect, dignity, and equality of all persons.5 It ensures that victims, survivors, families, and all those impacted by these tragedies are treated with the respect, compassion, and dignity they deserve, and their rights are respected and protected.

It provides a supportive environment; coordinates services; and ensures victims have the information they need, an opportunity to be heard and to participate, and be assured that their safety and protection is considered at all stages of the response.

Major incident response strategies must also include the added layer of capacity to respond to what we know will be some of the “predictable challenges” faced in a mass casualty incident:

- identification of victims

- management of victim/family response

- communication

- resource coordination

- impact on responders and service providers6

LEAs will need to determine in their planning process who will oversee and carry out victim-related tasks for their agencies and which organizations they will partner with or call upon for assistance with community-wide planning and protocols. According to FBI Assistant Director of the Victim Services Division (Ret.) Kathryn Turman, established relationships and agreements in place ahead of time will also help LEAs determine their responsibilities versus those of other organizations for addressing longer-term needs and rights of victims.

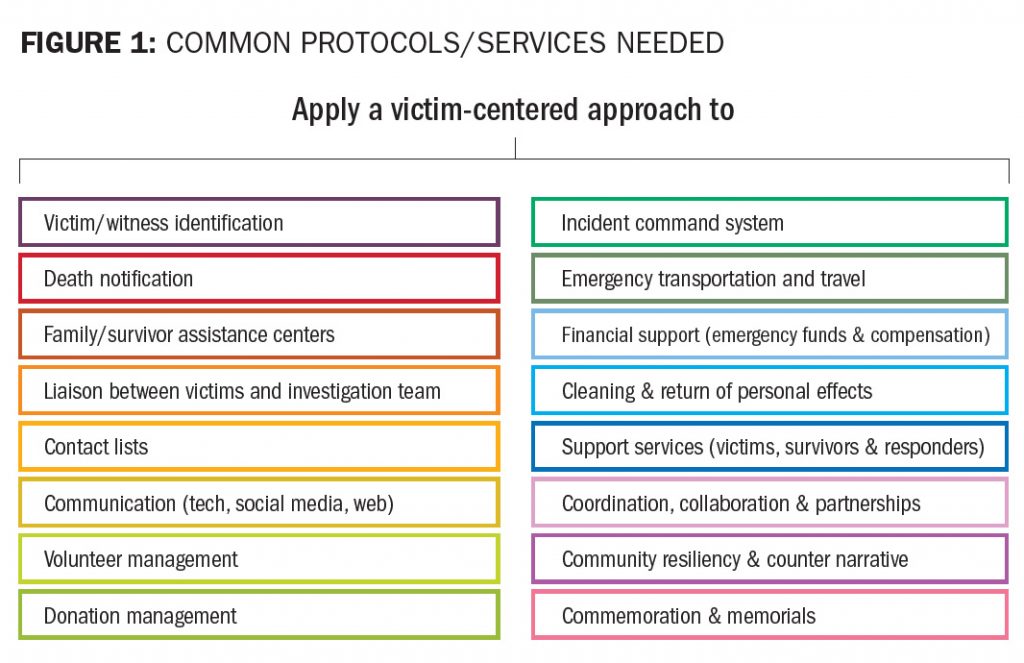

Police leaders should ensure that their planning and response strategies include protocols that are typically needed in the event of a mass violence incident. (See Figure 1.)

Overview of Victims’ Needs

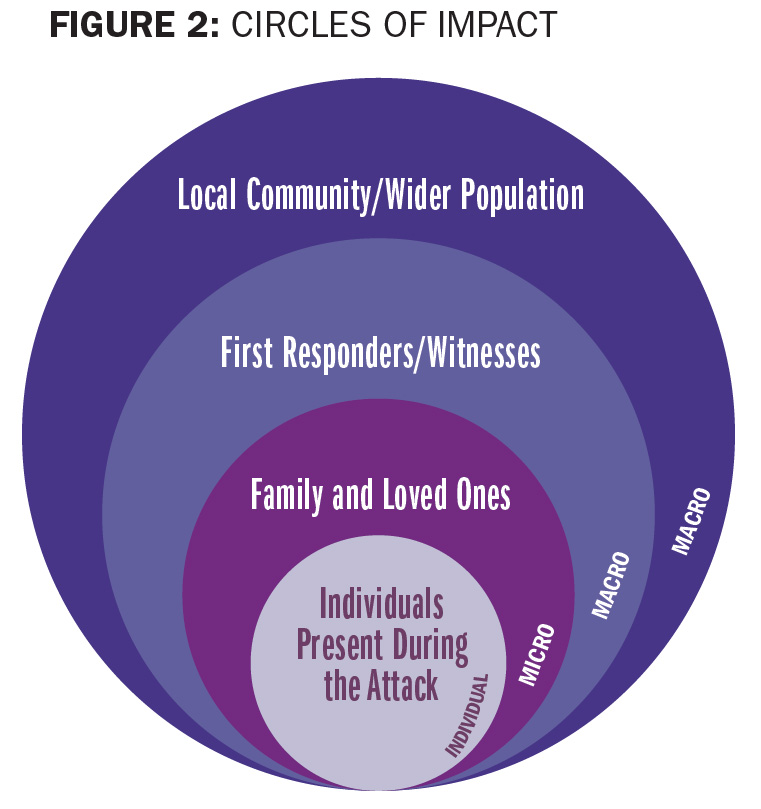

Who is a victim? Although legislation in many countries defines who a “victim” is, an effective strategy will adopt a broad definition of ‘victim’ from the outset. Incidents of terrorism and mass violence impact not only victims (including survivors and witnesses) and their families and loved ones, but also first responders (e.g., police officers, paramedics, firefighters), other service providers (e.g., victim support services), and the broader community—all of whom are faced with the challenge of coping in the aftermath.

The term “circles of impact” considers the potential for harm when victims and their families are affected, as well as their communities and society as a whole, as shown in Figure 2.7

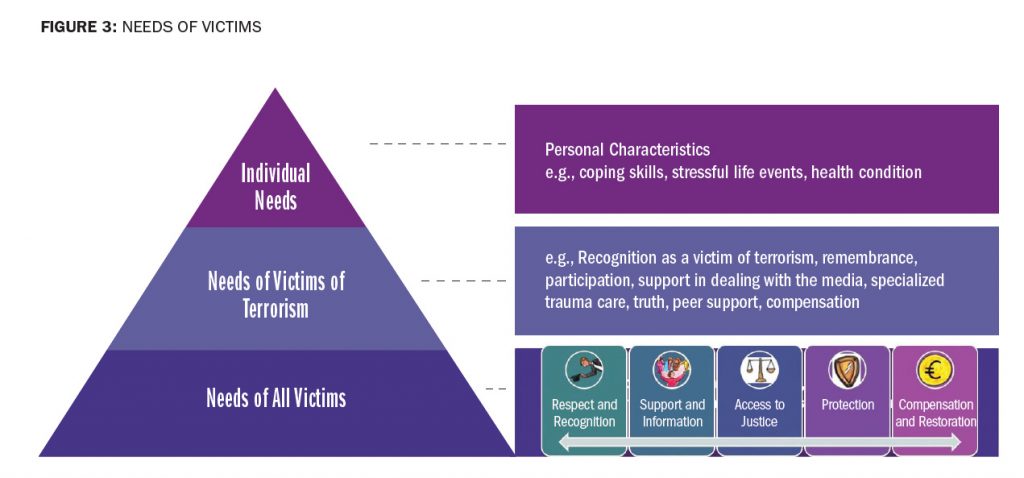

What are victims’ needs? While every victim is unique, there are common themes in relation to victims’ needs that must be considered and provided for in agencies’ preplanning and response strategy in the short, medium, and long term. Having a needs assessment process in place will assist with ensuring that victims’ needs are identified and the appropriate supports are in place.

Benefits of a Victim-Centered Approach

The benefits of implementing a victim-centered approach not only impact victims, but support agencies in other areas such as public trust, first responder wellness and resiliency, and investigations.

Public Trust and Confidence: The victim-centered approach helps build trust and enhances cooperation from victims and the public. It demonstrates commitment to victims and communities by supporting government officials, first responders, community partners, nongovernmental organizations, other stakeholders, and the public by providing the information and expertise they need in a time of crisis. The approach also enhances the capacity of police services to provide victims with entitlements under victims’ rights legislation and ensures that victims will be informed, considered, supported, and protected.

Support for Those Impacted: A victim-centered approach offers significant benefits for victims and their loved ones in the context of mass victimization. It allows them to feel heard and promotes healing and resiliency. It also reduces the potential for further harm, revictimization, and post-traumatic stress. There can also be an impact to responders and service providers when they do not have the resources, knowledge, or capacity to help those who have been affected by the incident. Knowing that victims and their loved ones are receiving the information, support, and care they need from others can help responders cope and be more resilient.

Investigative and Operational Priorities: A victim-centered approach with trained victim specialists or family liaison officers linked to incident command and major investigations will help facilitate the identification and location of and communication with victims and witnesses. A positive relationship with the families will need to be in place from the beginning—trust can be built over time, when trained victim specialists or liaisons are embedded in the response strategy from the start.

As demonstrated by the aftermath of 9/11 and other tragedies, victims will have needs that go well beyond the incident. As the investigation progresses following the incident, there will be public accountability, whether it comes as a criminal trial, inquest or inquiry, or commission. A positive relationship between the investigators and victims, witnesses, and families is helpful to future success, as mentioned, for building ongoing public trust in the police.

This approach also creates a pool of subject matter experts who can be consulted to ensure a victims’ lens is applied in development and review of emergency response plans.

As stated by Maria McDonald, the victim services lead at the Ontario Provincial Police:

The goal of an effective planning and response strategy is to build a tiered, scalable, resilient victim-centered response which empowers victims, facilitates investigative excellence and supports the health and well-being of your people and your communities.8

Collaboration, Preplanning, Implementation, and Testing

It is the leadership, advocacy, and voices of victims, survivors, and families that has informed and inspired police leaders to turn policy, best practices, and lessons learned into action. Leaders like Mary and Frank Fetchet from VOICES Center for Resilience; Susheel Gupta, director of the Air India Victims’ Families Association; and Maureen Basnicki, cofounder of the Canadian Coalition Against Terrorism, are just a few of the many victims and family members who use their advocacy and leadership to influence change at the local, national, and international level.

It is the leadership, advocacy, and voices of victims, survivors, and families that has informed and inspired police leaders to turn policy, best practices, and lessons learned into action. Leaders like Mary and Frank Fetchet from VOICES Center for Resilience; Susheel Gupta, director of the Air India Victims’ Families Association; and Maureen Basnicki, cofounder of the Canadian Coalition Against Terrorism, are just a few of the many victims and family members who use their advocacy and leadership to influence change at the local, national, and international level.

They have provided the momentum, support, and access to expertise to move forward on implementing key initiatives in relation to the victim-centered approach in the preplanning and response strategies to terrorism and mass violence, as evidenced by and reflected in the work of the Leadership in Counter-Terrorism Alumni Association (LinCT-AA) and INVICTM, among other organizations.

Since its inception in 2008, the LinCT-AA has brought together senior police and intelligence leaders from the Five Eyes to promote personal and professional development, networking, exchange of good practices, and global thinking. LinCT-AA leaders continue to ensure that victims have been included in and considered as essential partners in the discussions and the work of the association.9

“It is the leadership, advocacy, and voices of victims, survivors, and families that has informed and inspired police leaders.”

In 2016, INVICTM was created, bringing together a group of trusted experts dedicated to improving support for victims of terrorism. Without a formal structure or legal entity, the group dedicates its time to sharing good practices and lessons learned, with the goal of enhancing support to victims of terrorism by furthering knowledge about terrorism victim needs. Built on trust and confidentiality, the group has grown as a platform for sharing knowledge and information and has become a forum for experts from around the world to leverage new information and expertise for use in their own countries.10

Police Leadership and International Collaboration

The following three examples demonstrate how the established relationships and collaboration between police leaders and advocates have ensured that the experience, knowledge and expertise of victims, survivors, families, and civil society have been used to inform, enhance, improve, and test plans and response strategies at the national and international level.

Operation Kenova (Northern Ireland): The use of a victim-centered approach in a major investigation is highlighted in the work of Operation Kenova. This independent investigation is being led by former Chief Constable Jon Boutcher.

Victims are at the very heart of Kenova, with the overriding priority to discover the circumstances of how and why people died—to establish the truth regarding those offences covered within the Terms of Reference.11

The Victim Focus Group (VFG) was established to facilitate transparency, oversight, and reassurance for victims’ families with regard to the adoption of a victim-centered investigation.12

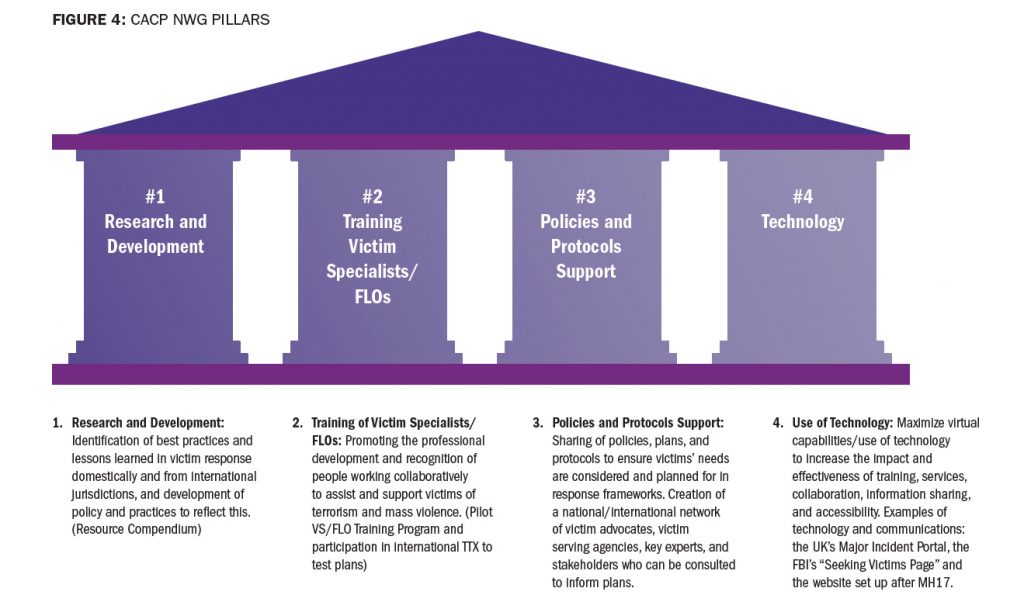

Canadian Association of Chiefs of Police (CACP) – National Working Group (NWG): The CACP NWG was formed in 2018 to bring together a group of senior police leaders and members to assist police services and communities in Canada increase the country’s preparedness by developing a more consistent standard of victim response across jurisdictions, with flexibility built in to respond in ways appropriate to the specific communities. The work of the committee is built around four pillars, as shown in Figure 4.

UK National Police Wellbeing Service (Oscar Kilo)/INVICTM/LinCT-AA: International Virtual CT Tabletop Training Scenario – Testing Victim Response and Member Support: In the spring of this year INVICTM collaborated with Chief (Ret.) Andy Rhodes, service director for the UK National Police Wellbeing Service (Oscar Kilo), and the LinCT-AA (supported by the CACP NWG), to conduct an international counterterrorism tabletop training exercise to test agencies’ response for victims and first responders from a well-being and victims’ lens in a terrorist or mass violence incident. The developers used immersive technology and the unique “I AM” concept to trigger the more human and emotional dimensions of the victim response and member wellness by drawing out practical and logistical issues through the simulated personal testimony of those affected.13

Conclusion

|

Thank you to the victims, survivors, families, first responders, and all those impacted by these tragedies for your courage and inspiration. To police leaders, victim advocates and victim serving agencies, thank you for what you do day in and day out to make a difference for so many. Special thanks to the members of INVICTM, LinCT-AA, and CACP NWG for your commitment, leadership, and support. This short article is informed by all your experience, knowledge, and hard work.

|

As families, communities, law enforcement, and the world reflect on the 20th anniversary of 9/11, police leadership must also reflect on lessons learned and their current practices and procedures in relation to preparing for and responding to mass victimization. The impact of mass casualty events on those who were directly or indirectly affected underscore the need for a strategic and coordinated approach to victims’ rights and support in the aftermath of such tragedies over the short, medium, and long term.

The key to the development and operationalization of a coordinated victim-centered response is preplanning and relationships with key partners established ahead of time and continuously strengthened, in order to collectively ensure victims are identified, their rights are protected, necessary protocols are in place, and victims receive the information, consideration, and support they need and deserve.

Notes:

1Svetlana Shkolnikova, “9/11 Victim Identification: DNA Techniques Advance,” NorthJersey, September 10, 2018.

2Noah Goldberg and Thomas Tracy, “So Many Deaths from 9/11-Related Illnesses, Victim’s Fund May Run Out of Money,” Seattle Times, September 10, 2018.

3Today, nearly 83,000 responders and survivors are in treatment for life-threatening illness and serious medical conditions. Over 4,100 have died from the 9/11-related illnesses they contracted.

4FBI Office for Victim Assistance and NTSB Transportation Disaster Assistance Division, Mass Fatality Incident Family Assistance Operations: Recommended Strategies for Local and State Agencies (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, 2013), 14.

5Ontario Provincial Police Victim-Centred Approach.

6FBI Office for Victim Assistance and NTSB Transportation Disaster Assistance Division, Mass Fatality Incident Family Assistance Operations.

7More information about the circles of impact can be found in the INVICTM 2018 Symposium report: INVICTM, Support Victims of Terrorism: Report of the INVICTM Symposium in Stockholm 2018.

8Maria McDonald (Deputy Director, Victim Support Strategy Lead, Ontario Provincial Police), presentation to CACP National Working Group (Spring 2021).

9 “Leadership in Counter Terrorism Alumni Association (LinCT-AA),” website.

10LinCT-AA, “INVICTM: International Network Supporting Victims of Terrorism and Mass Violence – 2018 Symposium Report.”

11Jon Boutcher, “An Investigation into the Alleged Activities of the Person Known as Stakeknife,” Operation Kenova Update, video 3:58, December 17, 2019.

12The Victim Focus Group Report is available at Operation Kenova.

13 UK National Police Wellbeing Service, “About Oscar Kilo.”

|

|

|

|

Please cite as

Mary Fetchet and Sue O’ Sullivan, “From Tragedy to Advocacy: Lessons Learned in Supporting Victims, Survivors, and Responders,” Police Chief 88, no. 9 (September 2021): 92–101.