In celebration of IACP’s 125th anniversary, each 2018 issue of Police Chief will include a republished article from the magazine’s history, which dates back to 1934. The following article was published in the October 1994 Police Chief.

IACP Through the Years article reprints reflect the eras in which they were first published and should not be construed as necessarily reflecting the IACP’s current view or stance on topics.

The origin of the insignia provides a cohesive framework through which the IACP’s history can be viewed. Throughout the historical account that follows, the power of this symbol emerges as a means of enhancing the image of the association, as well as the cohesiveness of its membership.

Webber S. Seavey, the chief of police in Omaha, must have been extremely disappointed. In November 1892, he had sent out 385 invitations to the heads of the largest police departments in the United States, urging them to join him in Chicago in May 1893 for the purpose of forming a national police organization. An added incentive to the proposed meeting was the opportunity to visit the World’s Colombian Exposition. This fair, which would open on May 1, 1893, was expected to be a truly magnificent event.

When roll call was taken on that historic Thursday morning, May 18th, only 51 chiefs had come to the meeting initiated by Chief Seavey. The lack of a larger turnout for such a potentially important meeting only served to emphasize the overriding need to create a spirit of cooperation among the nation’s police departments. As one of the 51 attendees recalled, it was a “perfectly obvious fact that there was no sort of cooperation between the municipal police departments of America.…”1 Others would have put it more strongly—that mistrust and destructive rivalry dominated the relationships among police agencies.

Regardless of their small representation, the 51 chiefs spent a busy three days in Chicago. They elected Seavey as their president and Harvey Carr, chief of Grand Rapids, as their secretary/treasurer. Then they began making organizational plans, devising programs, considering resolutions and taking advantage of the various entertainments offered them. They had an opportunity to see the fair and, by special invitation, an afternoon performance of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show.

By the time this initial organizational meeting had ended on May 20, 1893, it was decided that the group would call itself the National Union of Chiefs of Police of the United States and Canada. They also resolved “that we, the members of this organization of Chiefs of Police, hereby agree to assist each other on all occasions….”2 At the start, this plea for cooperation was seen as essential to the attainment of their most important objective—the establishment of a national bureau for the identification of criminals.

The next year, the newly formed union met in Saint Louis. The attendees celebrated their first birthday anniversary as well as the fact that their membership had increased to 113. More importantly, the group adopted a resolution calling on the speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives to “establish in connection with the Department of Justice, a Bureau for the identification of criminals and the dissemination of criminal information.”3

Over the next few years, the chiefs made numerous efforts to petition Congress for support of this keystone program, but the only result was a condition of collective frustration. Finally, at their 1897 convention in Pittsburgh, Jacob Frey, the marshal of Baltimore, showed his prescience when he cautioned his fellow members about the focus of their efforts to create a national bureau of identification. “If they waited for Congress to act, they would all be in their graves; the only way to get it was for the police to establish it themselves; after that the government could become interested.”4

Frey’s wisdom was accepted and, by the end of this convention, resolutions were passed that called for the establishment of a National Bureau of Identification (NBI) in Chicago. Members of the association who paid their $5 annual dues were eligible for bureau membership. They were, however, required to pay an additional assessment for the bureau’s services. These fees ranged from $10 to $100, depending on the population of the member city.

After this meeting ended on May 13, the chiefs acted quickly. On October 20, 1897, the organization, now known as the National Association of Chiefs of Police of the United States and Canada, opened the long-awaited bureau in Chicago’s city hall. The new bureau had its own board of governors with a president and a secretary, as well as full-time salaried expert in identification procedures who served as its superintendent. The NBI was now ready to circulate Bertillon measurements, photographs and criminal information among its subscribers.

Very soon after it became operational, the NBI’s services became recognized as a valuable source of information—not only by subscribers but also by those who could not afford to participate or were ineligible to belong to the association. Problems arose when a number of persons, both members and non-members of the association, tried to avail themselves of the bureau’s information without paying the additional assessment. By and large, this problem was dealt with by the introduction of identifying wreathed insignias to be displayed on the letterhead of all paid subscribers.

As the association’s membership, activities and influence increased, the member chiefs also had a need to identify themselves to one another in their official correspondence. The solution to this was the distribution of a rubber stamp to each member in good standing. The dates on the stamp were to be changed each year.5

As the century drew to a close, the association’s leaders were convinced of the value of the benefits their members received for their $5 annual dues. Nevertheless, the challenge they faced was to persuade additional chiefs to become members. At the 1898 convention, Chief Janssen, the association’s president, said he did not feel it was necessary “to beg for people to join us.” He recommended a more indirect approach, asserting that “those who are not members be treated in a manner that will deem it important and a privilege to join.”6

This attitude also applied to the NBI—perhaps even more so. Though the association’s membership had grown to about 160 chiefs by 1899, it was disheartening that only 35 of them were paid subscribers to the bureau.

During the first years of the new century, crime increased, criminals moved more freely among cities, President McKinley was assassinated and the anarchists were kept under the watchful eye of the police. In light of these conditions, both members and non-members needed, more than ever before, up-to-date criminal information. This, in turn, placed greater demands on the NBI—directly by subscribers and indirectly by non-subscribers who sought desired information as a confidential favor from those they knew who had paid their pro rata fee.

The association’s ninth annual convention, held in Louisville in May 1902, marked a year of change. Article I of the new constitution showed for the first time the name of the International Association of Chiefs of Police. With this expanded scope for its activities, discussions at the convention included such topics as the use of the international language—Esperanto—and the assistance of the U.S. State Department in encouraging greater participation by police officials from abroad.

The NBI was moved to Washington from Chicago, and a new superintendent was appointed. The president of the bureau’s board of governors, Chief Deitsch of Cincinnati, reported to the members that he had visited the bureau in its new Washington office about two weeks before the start of the convention and found it in first-class order.

Other things about the association remained unchanged. Major Richard Sylvester, superintendent of the Metropolitan Police, Washington, D.C.—elected president of the IACP in a heated contest the previous year—was unanimously reelected to the office. Harvey Carr remained as the secretary/treasurer. The need to increase membership persisted.

Predictably, the leaders of the association continued to be thwarted in their appeals to the U.S. Congress for support of the NBI. Concepts of cooperation, brotherhood and unity were again voiced by the members, although their specific meaning was often unclear. Sometimes these pleas referred to the ideal of fraternal unity among all chiefs of police. Other times, these expressions of cooperation were meant in a restrictive sense, applicable to members only.

In March 1903, the chief of police of Rotterdam, Holland, proposed in a letter to President Sylvester that measures be adopted to improve the means of identifying IACP members to one another. The chief suggested that a current membership list be sent each year to those members who had paid their dues. He also recommended that each member write after his signature on all confidential correspondence the letters “MIACP,” indicating his membership in the association.

In his annual address to the attendees at the May 1903 convention in New Orleans, Sylvester used this letter as evidence of the association’s success in building closer relationships with colleagues abroad. He considered the ideas in this letter as food for thought.

During the first day of the June 1904 convention in St. Louis, Sylvester gave an unusually long address to the membership. Near the end of his wide-ranging oration, Sylvester said,

It has been suggested to me by a representative of a foreign government that the Association adopt a miniature official design, to be registered with the government, which would be a trade mark to be attached to the letterheads and official paper used in communicating between departments which maintain a membership in the International Police Association. The question is submitted to you for such action as you deem necessary.7

For the moment, the chiefs did not deem any action as appropriate. They did, however, act on the choice of a convention site for the following year. When Chief Wittman of San Francisco described the many attractions of the “Metropolis of the West” and promised the members that they would never regret their vote, they enthusiastically chose “Frisco” for their 12th annual session, the first to be held west of St. Louis.

Early in 1905, Robert A. Pinkerton and his brother William communicated with President Sylvester about the need for an insignia for the IACP. The Pinkerton brothers, two of a small number of private detectives who were members of the association, were “never asleep” to an opportunity to enhance the competitive advantage of their national detective agency. Sylvester assured them that action on the matter was being taken.8

A few months before the scheduled Frisco convention was to begin, Colonel Wittman lost his job as San Francisco’s chief. He told the association’s officers that it was now impossible to have a successful meeting in that city.

Contrary to Wittman’s assurances at the 1904 convention, the officers who received his cancellation message much regretted the choice of San Francisco for the site of their 1905 convention. Sylvester and his IACP officers hurriedly met in Pittsburgh in late March to deal with this emergency, and various alternative cities were considered. By the time this meeting ended, the group had agreed to hold the 12th annual convention in Washington, D.C., leaving Sylvester free to choose the specific dates in May for the event.

Sylvester now moved rapidly to make all the necessary arrangements. By April 4, he was able to supply Harvey Carr, the association’s venerable secretary, with all the information about the change in plans. The secretary sent a letter to his IACP brothers telling of the change in venue and assuring them of a “pleasant and profitable meet…at the Capital City.” Characteristic of Sylvester’s attention to detail, the letter specified all of the arrangements that had been made, including reduced railway rates and the main course of planked shad to be served a banquet hosted by Washington’s Board of Trade.9

Despite the burdens of these last-minute activities, Sylvester was ready with another lengthy annual report and address when the opening session began in Washington on May 22, 1905. Near the end of his encyclopedic message, he said,

The members of this Association have been furnished with a new means of knowing each other by the issuance of an Association monogram including the letters “I.A.C.” and the word “Police.” This combination was arranged by your President and Secretary in convenient and attractive form, to be used upon your official stationery and also produced in the form of a badge or button to be worn upon your person.10

Before he concluded his remarks on the subject of the new IACP monogram, he assured the chiefs that the design “has been registered under the law with the proper authorities in the United States Patent Office as the proper way of securing it from improper or illegitimate use by designing persons.”11

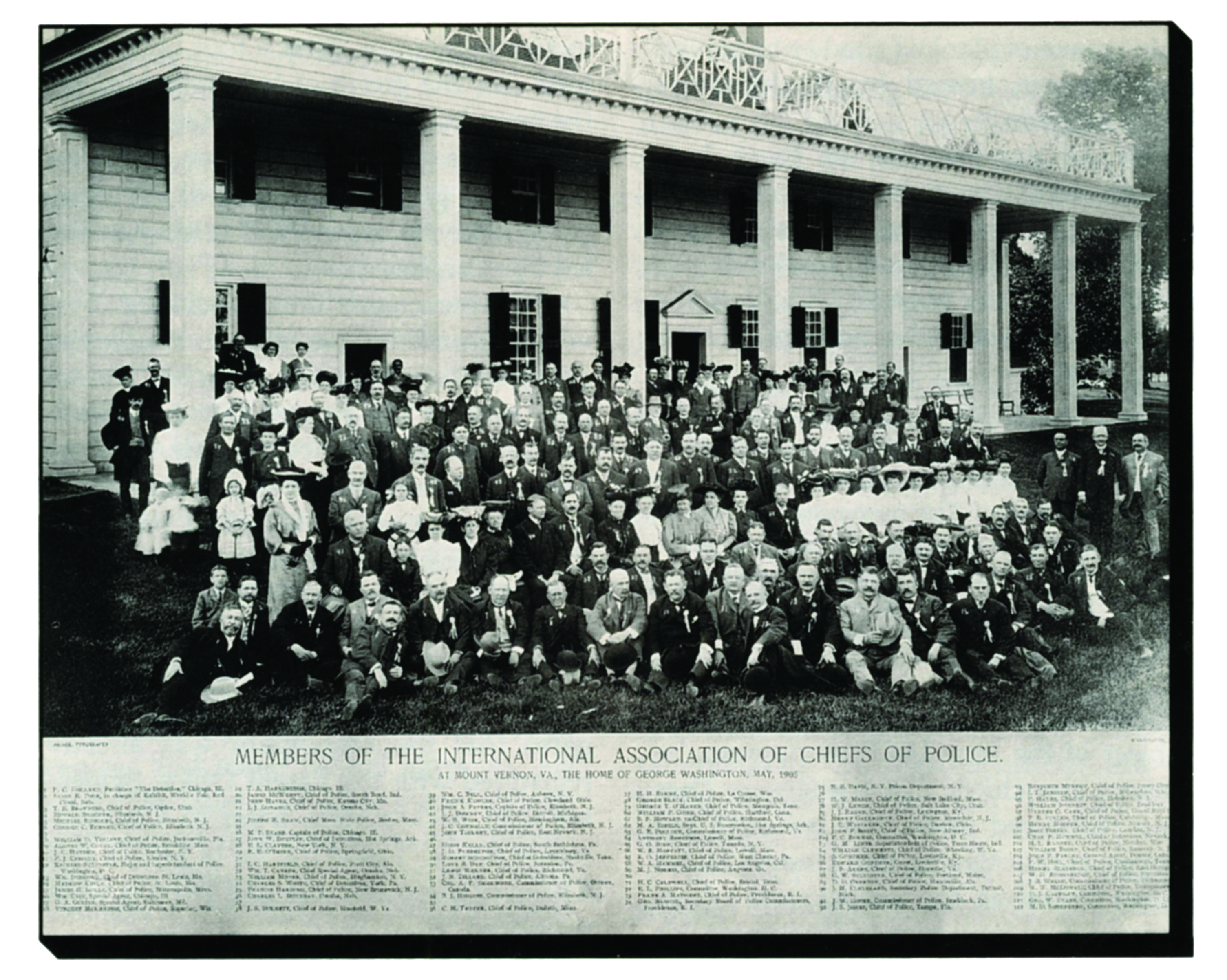

On the following day, during an intermission in the proceedings, a lapel button showing the association’s new monogram was distributed for the first time to all members present. Later, when the morning session concluded, the group traveled to Mount Vernon. After a tour of the historic site, the group of 112 assembled on the lawn in back of George Washington’s home for a group picture (see photo on preceding page). Almost all of the delegates wore the new IACP button in the left lapel of their suits.

After the convention concluded, Sylvester returned to his office to handle the many tasks remaining from his pivotal role. Among the papers that had accumulated in his absence, he found a letter from the commissioner of patents stating that his petition for a design patent of the IACP insignia had been approved as he had requested in his letter of May 17. Inadvertently, the term requested for the patent had not been specified. Aware that he had assured the convention delegates that the monogram was already registered with the Patent Office, Sylvester fired back a terse letter to Commissioner Allen: “I paid the fee of $10.00, and a term of three and one-half years is what is desired.”12

Despite the protection now given the design by the U.S. Patent Office, by the time the association met in April of the following year in Hot Springs, Arkansas, instances of misuse of the emblem began to occur. This was brought to the attention of President Sylvester by several members. Non-members, particularly those persons in private detective agencies, had sought to gain the privileges and prestige of membership in both the association and the NBI by displaying the emblem on their letterhead and in their advertising. Sylvester exhorted the members by saying, “If any members should hear of anyone using our insignia illegally, I will be glad to take action against [him] as we have done before.”13

On the last day of the convention, the attendees unanimously re-elected Richard Sylvester to the presidency for his sixth term. The election was described as a “veritable love feast (sic).” Traveling back to Washington, D.C., from Hot Springs, Sylvester felt pleased with his re-election and the general acceptance given to the IACP monogram. He was a man who respected history and believed that symbols were an important—indeed, almost sacred—mark of an organization. He was also a man on the alert for those who violated the authority of the insignia.

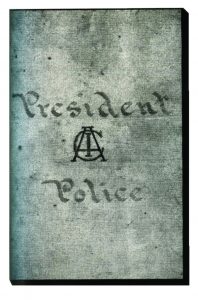

As president of the IACP, Sylvester meticulously kept a bound copying book for his outgoing association correspondence. On the cloth cover of his then-current ledger, he skillfully lettered the word “president” and below that drew the association’s new emblem.14

By this time, the system of distinguishing members of the IACP and the NBI from non-members appeared to be working well. The proper display of the engraved identifying emblems on official papers carried with it the prestige of membership in an exclusive fraternity and the authority for access to confidential criminal information. Those who misused the official insignia were severely dealt with on a case-by-case basis.

However, the members of the bureau’s board of governors were concerned with more critical problems. By 1909, there were only 70 subscribers to the NBI. Not only did this small membership limit the bureau’s income, but it also narrowed the scope of information filed in the clearinghouse. Obviously, the more information submitted to the bureau, the greater the possibility that current and pertinent information could be sent back in response to a member’s request.

The bureau continued to be improperly burdened by subscribers who obtained information as a favor for certain non-member agencies. This problem had become especially acute, with abuses being perpetrated by both private detective agencies and some federal agencies. Although the chief post office inspector, the commissioner of immigration and the adjutant general of the U.S. Army were members of the IACP and paid their fees to the NBI, other agents in the departments of Justice, Treasury, Commerce, Labor and Interior did not pay. Some member chiefs were troubled by denying an informal request for criminal information when it came from a Justice Department agent or a member of the Secret Service whom they knew and trusted.

By 1910, the situation had become untenable, threatening the successful operation of the bureau. As these difficulties accumulated, the officers intensified their efforts to seek solutions. Chiefs in smaller cities, largely underrepresented among the subscribers, were urged to join the bureau, while chiefs in the larger cities were encouraged to assist smaller jurisdictions in becoming active participants in the clearinghouse. Moreover, the leaders of the association importuned Congress for financial support with a sense of greater urgency.

When the association convened in Birmingham on May 10, 1910, Sylvester told the members that they were closer to obtaining government aid than at any previous time. The president was right! Less than two months later, the bureau received its first government aid—$3,000—covering the next 11 months’ operations.

The IACP had sought government support for the bureau since 1894; 16 years later, that objective was finally attained. However, the financial support received was not its salvation. Under the act authorizing the aid, Congress obtained the assurance that all U.S. government departments would be entitled to information from the NBI under the same conditions as the police.

The net effect of this initiative made it difficult for the NBI to function on a fiscally or operationally sound basis. Significantly more demands were made on the bureau by the new subscribers from the various levels of federal government, as well as by those from small towns who paid the lowest pro rata fees. Penal institutions, parole boards, railroads, civil service commissions, navigation companies and even private organizations working under a government contract now sought criminal information directly from the bureau. The situation was further aggravated by the continuing efforts of private detection agencies to clandestinely obtain criminal information from the NBI files.

As a consequence of this increase in demand for information, the insignias of both the association and the NBI became more frequently misused. The problem was confronted at the association’s 19th annual convention, the first to be held outside the United States. Meeting in Toronto July 9-12, 1912, the members discussed—among other things—the misuse of the insignia by “all kinds of people,” and passed two resolutions to address the problem. They first specified that “the use of the patented insignia of the association shall be confined to the active membership…”; the second, that “the Secretary be directed to call in the insignia of all those who are not entitled to have them.”15

As follow-up to these actions, Sylvester and Carr considered approaches that would be more effective than a call-in of fraudulent insignia. They first discussed the issuance of a new insignia that would be distributed only to active members. The redesigned insignia they considered was drawn by an artist and consisted of the already patented arrangement of letters, embellished by a surrounding sunburst pattern.

This plan was not pursued for a number of reasons. Sylvester was cautious because he did not “…want to lose the value of the patent by reason of any embellishment we may add to it.”16 Carr was against the idea for more practical reasons, including the work and expense of getting out a new electrotype, and the cost and confusion of the members’ having to change their department’s stationery.

The Pinkerton brothers encouraged the president to adopt whatever measures were necessary to stop the improper display of IACP’s emblem. They both supplied Sylvester with the names of competing detective agencies that misused the insignia, and urged that these violators be dealt with. If a modification in the design of the emblem was to be tried, that was acceptable to them.17

In the final analysis, no change in the emblem was made because that action was not authorized in the resolutions passed at the Toronto convention. Both Sylvester and Carr continued to confront violators brought to their attention, demanding that they cease the display of the emblem. Carr observed to Sylvester that he had yet to find anyone who refused to comply with his request to discontinue the improper display of the insignia. The threat of “unpleasant consequences” was sufficient to bring about compliance.

Despite the efforts of Sylvester and Carr, complaints about the misuse of the IACP emblem continued to be voiced by some members. During the June 1914 convention, held in Grand Rapids, the problem of the emblem’s unauthorized use erupted. During the discussion, Carr said that in the past decade he had written to “15 or 20 people,” notifying them that if they did not stop the unauthorized use of the insignia, drastic measures would be taken. “Some people discontinued it, and some people kept right on using it,” Carr noted.18

One chief at the meeting complained loudly of a detective, a “howling disgrace” in his community, who used the emblem without proper authority. As the discussion became more heated, legal prosecution of the violators was considered. The remedial actions of both Carr and Sylvester were challenged. Sylvester responded as follows:

I think it well, while this insignia matter is up, that we should make it prominent, make it public. We have nothing to hide. So far as I am concerned, I will state I have written in this connection to a number of these men, stating our law, stating the fact that the insignia is registered. I designed it myself and had it registered in the Patent Office. I am the author of that insignia and have endeavored to protect it in every way I could. 19

The discussion then focused on various interpretations of active and honorary membership and the conditions under which the emblem could correctly be used. The matter was finally brought to a conclusion with the unanimous adoption of a resolution: “That the use of the insignia of this Association by unauthorized persons be stopped, and that the President of the Association take legal proceedings, after due notice.”20

When the members finally began the election for the office of president, Sylvester was again selected for the position. Afterward, when the office of secretary/treasurer was considered, Carr quickly announced that since he was going to retire as superintendent of police, he wanted to decline nomination for the office. He emphasized his decision by saying, “You have treated my declinations in years gone by as a joke. This time it is in dead earnest, and I cannot take the office.”21

Frank Cassada, the chief in Elmira, New York, won the office and—for the first time since the start of the organization in 1893—Carr was not its secretary/treasurer. In honor of his long service, Carr was elected a “life member without dues,” one of three persons so honored.

After the election was completed, reference was made to a police directory that had been compiled by Sylvester. A resolution regarding this publication—unanimously passed by the membership—read as follows:

Resolved, That the International Association of Chiefs of Police extends to its President, Major Richard Sylvester, its thanks and appreciation of the Police Directory compiled and published by him without expense to this Association. It is a valuable work for which all of us find use.22

In his concluding remarks, Sylvester extolled Carr’s many contributions to the association during his service as secretary/treasurer. The president also reemphasized the value that solidarity, unity and fraternity played in the development of the association. However, his last words at this notable convention were about the organization’s insignia. He observed that the association’s insignia and button could be obtained from the new secretary/treasurer and specified that “the insignia with the wreath is that of the [National] Bureau of Identification.”23

When the chiefs returned to their cities and resumed their official duties, they now had the newly published “Directory of Police and Prisons” as a ready reference.24 This compilation, copyrighted by Richard Sylvester, contained the names of over 600 chiefs of police and heads of state and federal prisons. In addition, it contained data about the various police departments listed, such as the method of identification (Bertillon or fingerprint) and the number of patrolmen on foot, bicycle, motorcycle or horse.

The inside cover of the publication contained this notice: “The insignia and designs of the International Police Association are protected by law.” Below this caution was the IACP insignia displayed in a newly ornamented form (pictured at right).

Those who recalled Sylvester’s last words at the grand Rapids convention about the wreathed insignia belonging to the NBI must have been surprised at what they saw. Here, for the first time, was the IACP insignia surrounded by a wreath and protected by a 1914 copyright held by Richard Sylvester! Concurrently, in an action not so visible to the IACP members, Sylvester had registered the unadorned membership mark with the U.S. Patent Office.25

There was another surprise for the members who attended the May 1915 convention in Cincinnati. Following Sylvester’s typical lengthy address on the first day of the meeting, the chairman of the Committee on Credentials reported that 41 persons had applied for active membership. The committee recommended that all be accepted, including Raymond W. Pullman, superintendent of police, Washington, D.C.

On the face of it, the convention proceeded as usual until the day of the election of officers—May 27, 1915. Early in the day, Sylvester stated the he was no longer a chief of police and added his opinion that the association should be guided by an “active hand.”26 He acknowledged that several delegations had spoken with him about submitting his name in nomination for president. Though grateful for their support, he felt committed to decline in each instance.

Nevertheless, when the voting began during the afternoon session, Sylvester’s name was placed in nomination for president. He responded by saying, “I gave expression to my views on this question this morning, and I fear I was not fully understood.”27 He said he was honored to be nominated, but he reinforced his earlier statement that he had retired. Ultimately, the members elected as their new president Michael Regan, chief of police in Buffalo, New York.

The Sylvester era was over. Before the convention ended, resolutions were passed honoring Richard Sylvester for his 14 years of continuous service as president and making him a life member of the IACP without dues.

Although the war in Europe was in its third year, the members’ discussions at the June 1916 convention in Newark, New Jersey, reflected little attention to the distant battles. Their concerns related to crime control, the election of officers and the choice of the next convention site. Michael Long, the host chief, was elected president, and Kansas City was chosen as the location for the next IACP convention.

The officers continued to battle for the preservation of the integrity of their insignia. Outgoing President Regan delivered a lengthy address in the tradition of his predecessor. At the start of his oration, he said it was of “vital importance” for the association to copyright its emblem. He then nominated “the Chief of Police of Washington, D.C., as a Committee of One to present the matter to the proper sources there. Should it be found impossible to have this done in general then I would advise that the matter be taken up in each state.”28 The president cited a New York state law that made it a misdemeanor to display, wear or use the emblem of an organization of which the person was not a duly qualified member.

On April 6, 1917, the United States declared war on Germany and entered the European conflict on the side of the Allies. Life changed quickly as the nation mobilized to win the war. Three days after the declaration, IACP President Michael Long talked of his patriotic duty and proposed to the Executive Committee that the Kansas City convention scheduled for June 5 through 8, 1917, be “indefinitely postponed.” They concurred with this recommendation and, on April 28, sent a bulletin regarding this decision to all members.

Long never had the occasion to preside at an IACP convention during 1917. He did, however, have an opportunity to introduce the secretaries of War and Treasury to a small group of the association’s officers attending a special meeting in Washington, D.C., on December 17, 1917. Secretaries baker and McAdoo both praised the police for their aid, cooperation and loyalty to the federal government.

Long also prepared a president’s report, which was appended to the publication of the proceedings of the June 1916 convention in Newark. In the midst of these trying times, he “urgently recommended” that a copyright for the association’s emblem be “secured at the earliest possible moment, thereby prohibiting the use of the emblem by others than those who are members of the Association.”29 The publication of the 1916 proceedings was also notable because, for the first time, the insignia of the IACP was prominently shown on the inside cover.30

The Kansas City convention was eventually held in June of 1918. From the welcoming address in which an observance was given to 11 Kansas City police officers who had lost their lives in the war, to a series of patriotic speeches presented during the concluding annual banquet, police involvement in the country’s war effort was the constant preoccupation of the attendees.

For other members, their war effort demanded that they be elsewhere. In the case of Richard Sylvester, he missed this convention—his first absence in 20 consecutive years. After he retired as chief of police, he took a job with the DuPont Powder Company, organizing and directing a large guard force for the protection of the company’s ammunition factories. His responsibilities were of critical importance to our military operations.

On November 11, 1918, Germany signed the armistice with the Allies, and the American people returned to their peacetime pursuits. The IACP held its first post-war convention in New Orleans in April of 1919. Though the usual routines were followed, much attention was given to matters arising from the aftermath of the war. For one thing, Sylvester proposed in a paper submitted in absentia the establishment of a nationwide employment bureau for returning soldiers and sailors.

When the time came for the superintendent of the NBI to give his report, he quickly brought up the perpetual problem with the organizations’ insignias. The emblems for both the association and bureau were being modified so often by members and nonmembers that these representations were becoming meaningless. To illustrate the confusion, he produced 20 letterheads, none of which showed the same insignia design. The superintendent strongly recommended that the form of the emblems be standardized through the use of the official cuts of both the association and the bureau.31

Sylvester, the creator of the IACP insignia, missed his second consecutive convention and was unable to join in the discussion about the protection of the integrity of the association’s emblem. (His wife had been injured in an accident, and he chose to stay with her.)

Though Sylvester’s presence at association activities was temporarily interrupted, his influence continued to be felt and his past contributions remembered. After a gap of exactly four years, he traveled to Detroit in June 1920 to attend the association’s 27th convention.

On the first day of the event, his reappearance was marked by a tribute. He was presented with an elaborately engraved parchment appropriately marked with his creation—the IACP insignia. The text recognized his many years of service to the organization and noted his election to the position of honorary president.32

Sylvester thanked the members at this session with an eloquent statement. The somewhat frail 63-year-old man closed his remarks by saying that he would hang the certificate where he could “gaze upon it for the remainder of my days.”33

The convention continued for three more days. In an almost ritualistic manner, the leaders expressed their concern for the National Bureau of Criminal Identification, noting that the bureau continued to have both financial and operational problems. Most of the embers still believed that these problems could be solved through the transfer of the bureau to the federal government. After the wartime experience had demonstrated the effectiveness of a centralized bureau, it was thought that the federal government would be more receptive to the idea. As usual, convention business was interspersed with various entertainments—in this instance, boat rides to belle Isle, baseball games, boxing matches and burlesque shows.

A blare of trumpets and a brass band greeted the members when they assembled in Montreal in July 1924 for their 31st convention. The opening ceremonies were stirring, discussions about such matters as the “revolver plague’ were grave and the closing parades were majestic.

To William Rutledge, Detroit’s police superintendent and the association’s president, the proudest moment of the convention came when he announced “the greatest advance step in the annals of police history…”34 The National Central Bureau of Criminal Identification and Police Information finally became operational as part of the U.S. Department of Justice on the first day of July.

In a letter from the newly appointed acting director of the Bureau of Investigation read to the delegates, Mr. J.C. (sic) Hoover predicted “…that within a period of 30 to 60 days, it will be running at a degree of 30 to 60 days, it will be running at a degree of 100 percent efficiency.”35 As the letter explained, one of the ways chosen to increase the efficiency of the new National Central Bureau was to base its identifications system entirely on fingerprints. The Bertillon system of measurements was simply discarded.

The association’s primary objective had finally been attained—just over 30 years after the framing of an 1894 resolution petitioning the U.S. House of Representatives to establish a national bureau. President Rutledge paid tribute to the “dogged tenacity” of the members who originated the idea and worked toward its realization.

This action had an unforeseen consequence. The much-protected insignia of the association’s national bureau no longer had any functional purpose, and it quickly fell into disuse. However, the members of the parent organization felt a proprietary right to the dress of its offspring’s emblem. Soon, the wreath began to appear as an embellishment to the original IACP insignia.

As the association’s activities continued over the next few years, the more decorative emblem appealed to the members and it began to be seen with greater frequency. The wreathed IACP insignia appeared with slight variations on many of the association’s artifacts, correspondence and records. Individual members created further variations when their local printers prepared their own unique letterheads. The problem was further aggravated by unauthorized persons who continued to display the emblem or its variant for improper advantage. Despite these problems, no copyright or trademark registration was obtained to protect and standardize the new form of the emblem.36

In January 1934, the association began the monthly publication of the “Police Chief’s News Letter,” the predecessor of the Police Chief magazine, with the wreathed insignia appearing in the center of the masthead. In the November issue, the heavily drawn emblem was lightened. Beginning in July 1935, still another change in design was introduced.

Although the use of the insignia in the masthead of the IACP’s new official publication was a form of de facto recognition of its status as a symbol, this could not be considered to represent its adoption as the official emblem. To the contrary, as part of the long-established series of the publication of convention proceedings, the 1935 report displayed the traditional unadorned emblem, as had been the case since 1916. This changed with the publication of the 1936 Kansas City convention proceedings, when no insignia whatsoever was shown.

At the 1937 convention in Baltimore, a new constitution was submitted to the membership by the chairman of the committee on Reorganization, Donald S. Leonard, a young captain in the Michigan State Police. This constitution was unanimously adopted on October 6, 1937. Consistent with this action, new rules for operating the association were later formulated by the board of officers and published in the January 1938 issue of the Police Chief’s News Letter.

Rule XII pertained to the use of the official insignia:

Every active member shall be entitled to one membership pin and the use of one cut of the official monogram…Only active members of the Association regularly engaged in police work and receiving governmental salary are authorized to employ the official monogram or insignia on their letterheads or in any other manner whatsoever.

Another section of the rule stipulated that no publication, advertisement, letterhead, document or article shall show the IACP insignia so as to imply approval by the association.

The rule assigned enforcement responsibility to the executive vice president and specified that the insignia be copyrighted.

The rule also required the designated officer to act in instances of a violation by giving notification, initiating expulsion proceedings, presenting the matter to the Federal Trade Commission or taking other appropriate legal actions against the violator.37

The News Letter continued by saying, “due to the fact that there have been so many variations of the official emblem or insignia of the IACP, the Board of Officers designated as the official Association insignia the design which appears in the masthead of this issue of the News Letter.”

The publication of this rule could not have been more timely. The next monthly issue of the News Letter called the members’ attention to a “get-rich quick” scheme. The notice stated:

[T]he IACP headquarters has received a number of complaints from members that a certain chief of police has sent them a letter soliciting money to develop oil lands….This letter has been written on the official stationery of the city and carries the official IACP monogram. Executive Vice President Rutledge has written this chief…enjoining him from further use of the monogram…

At first glance, an enduring system for assuring the integrity of the IACP insignia seemed to be in place, and the responsibility for its enforcement had been designated. Still, the status quo did not allow for complacency.

At the 1938 convention in Toronto, Executive Vice President Rutledge said in his annual report that there had been a great deal of improper and unauthorized activity with respect to the association’s insignia. He told the members that he had served notice on a number of organizations and persons who had falsely represented the association.

Rutledge explained that “your officers open themselves to the criticism of those who stand to gain by these practices,” adding that “we have, nevertheless, taken the point of view that the reputation of the Association is at stake and that we must discharge our responsibilities….We must be ever vigilant to suppress such practices.”38

For over 100 years, the association’s members have worked for the betterment of their profession. The basic design of the IACP insignia has existed for almost 90 years. Though this historical account of the origin of the insignia has focused on the work of Major Richard Sylvester, the enduring character of the IACP insignia stands as strong evidence of the collective pride and respect the members hold for all of their predecessors and their accomplishments.

Throughout time, the IACP emblem has well served its identifying function. Beyond that, the widespread and repeated display of the emblem by the association’s members has resulted in its taking on a symbolic function. It has become the universally recognized mark of a proud organization, one that has struggled through difficult times to establish itself on a sound and respected basis, has worked to provide substantial benefits for its membership and has made significant improvements in the police profession. This simple alphabetical configuration has become more than a design. It is a unifying symbol, something worth fighting for in order to preserve its integrity and its historical meaning.