I will never forget responding to a 911 call downtown and seeing a six-foot-five man in sandals and a long, flowing dress screaming and yelling on the street corner. He started walking out into traffic, and I knew that waiting in my patrol car was not an option. As I jumped out of the car, he started moving toward me, then abruptly changed direction. He wasn’t armed, but I couldn’t get near him or calm him down. Then, the white CAHOOTS van pulled up and my shoulders relaxed. A responder in casual clothes stepped out of the van and engaged the man in conversation. I got back in the car and pulled away.

In every U.S. city, patrol officers spend most of the day responding to calls for service that are social issues rather than crimes. Some officers complain about having to do the job of social workers but are resigned as public servants to handle these calls. But there is a better way: police in Eugene, Oregon, where I spent most of my career, have been handing off these calls for service to civilian responders since the 1980s. I saw the need for other cities to follow suit when I became chief of the Olympia, Washington, Police Department.

Chiefs need to know that they can free their departments from calls for service that their officers may be ill-equipped to handle while improving long-term safety outcomes for the community. To accomplish this, chiefs need to “hug the cactus”—face up to something uncomfortable—and bring in civilian responders.

Part I: The Problem

For years, politicians and police executives have been repeating phrases like “addiction is a public health issue, not a criminal justice issue,” “we’re asking police to do the job of social workers,” and “we can’t arrest our way out of this problem.” Yet, patrol officers still spend much of their time handling addiction, mental health crises, and other social issues. Until there is a better option, the public will continue to react to these issues by dialing 911, and the police will remain the default responder for these calls.

Any veteran patrol officer can think of a call for service where they felt dismayed that they were asked to deal with something they weren’t trained for or equipped to handle. Law enforcement agencies receive a constant stream of calls that are related to issues like substance use, mental health disorders, and homelessness.

The Vera Institute and the New York Times each have analyzed 911 call data for large U.S. cities and concluded that less than 2 percent of all 911 calls for service to police relate to serious violent crimes.1 A recent report by the Law Enforcement Action Partnership (LEAP) and Center for American Progress (CAP) identifies the common low-priority call types that actually consume police time: disturbance, suspicious person or vehicle, noise complaint, well-being check, intoxicated person, mental health, and drug violations.2 Some of these calls need a responder with a badge and a gun. Most do not.

| Table 1: Most 911 Calls for Service Are Low- or Medium-Priority Percentage of total calls for service in 2019, by priority level |

|||||

| Call priority level |

Detroit, Michigan |

Hartford, Connecticut | Portland, Oregon |

Seattle, Washington |

Tucson, Arizona |

| Low | 40.4% | 23.4% | 43.3% | 45.4% | 33.7% |

| Medium | 32.8% | 42.3% | 27.5% | 36.3% | 40.3% |

| High | 26.7% | 34.2% | 29.3% | 18.2% | 26.0% |

| Table: Center for American Progress Source: The authors conducted original analysis using data from the following sources. Hartford Data, “Police Calls for Service 01012016 to Current: 2019 ANALYZED”; City of Detroit Open Data Portal, “911 Calls For Service: 2019 ANALYZED“; City of Seattle Open Data Portal, “Call Data: 2019 ANALYZED”;City of Portland Police Bureau, “Dispatched Calls for Service: 2019 ANALYZED”; City of Tucson, “Tucson Police Calls for Service – 2019 – Open Data.” | |||||

| Table 2: Types of Low-Priority 911 Calls for Service* Percentage of total calls for service, by call type |

||||||||

| Call classi- fication** |

Detroit, Michigan | Hartford, Connecti-cut | Minne-apolis, Minnesota | New Orleans, Louisiana | Portland, Oregon | Richmond, California | Seattle, Washing-ton | Tucson, Arizona |

| Disturbance | 14.7% | 5.4% | 7.7% | 2.2% | 7.8% | 2.5% | 5.2% | |

| Other complaint | 16.9% | |||||||

| Suspicious person | 4.2% | 3.0% | 4.7% | 5.2% | 0.2% | 3.3% | 1.1% | |

| Noise complaint | 3.3% | 1.6% | 1.0% | 3.4% | ||||

| Suspicious vehicle | 0.7% | 1.3% | 2.7% | 0.5% | 1.0% | 0.1% | ||

| Intoxicated person | 0.4% | 0.2% | 0.1% | 1.6% | ||||

| Well-being check | 1.2% | 4.0% | 1.1% | 2.1% | 0.3% | |||

| Mental health | 0.6% | 1.8% | ||||||

| Drug violations | 0.4% | 1.3% | 0.5% | 0.8% | ||||

| * The call classifications in this table are a sample of types of low-priority 911 calls and not an exhaustive list. ** Some classification titles differ slightly by city. “Disturbance” includes calls labeled as disorderly conduct; “Suspicious person” includes calls labeled as investigative person, unwanted person, and suspicious activity. “Noise complaint” includes calls labeled as music-loud, loud party, party (in progress), and music (in progress); “Suspicious vehicle” includes calls labeled as investigative vehicle; “Intoxicated person” includes calls labeled as drunk in public; “Well-being check” includes calls labeled as welfare check; “Mental health” includes calls labeled as mental not violent and mental patient; “Drug violations” includes calls labeled as “narcotics.” Table: Center for American Progress Source: The authors conducted original analysis using data from the following sources. Hartford Data, “Police Calls for Service 01012016 to Current: 2019 ANALYZED”; City of Detroit Open Data Portal, “911 Calls For Service: 2019 ANALYZED”; City of Seattle Open Data Portal, “Call Data: 2019 ANALYZED”; City of Portland Police Bureau, “Dispatched Calls for Service: 2019 ANALYZED”; City of Tucson, “Tucson Police Calls for Service – 2019 – Open Data”; City of Minneapolis, “Public 911 Call Problem Types”; City of New Orleans Open Data, “Calls for Service 2019”; City of Richmond, “RPD Calls for Service – Calls per Month, by Priority (2019-Present).” |

||||||||

Part II: The Solution

Police have been the default backstop for social problems for so long that it’s hard for them to imagine handing off a call for service to anyone else. But in the 1980s, the Eugene, Oregon, Police Department decided to let social workers from a local clinic carry police radios and respond to calls in a white Sprinter van; they called the program Crisis Assistance Helping Out On The Streets (CAHOOTS).3

This was a radical experiment at a time when many still thought the “drug problem” could be solved by arresting everyone who used drugs. The author was a bright-eyed young officer excited about driving fast and taking bad guys to jail—“bad guys” meaning anyone who caused a disturbance, and he wondered if these CAHOOTS “hippies” were going to turn a blind eye to criminal behavior or even facilitate crime.

The answer came as soon as CAHOOTS started working on the street:

On a cold, rainy winter day, I responded to a wellness check call to find a homeless man passed out behind some bushes in the park. I tried to wake him, knowing that even if he woke up, I couldn’t force him to go anywhere. But he was facing the risk of hypothermia, so I couldn’t just walk away. When he woke and saw a uniformed officer standing over him, he started swearing. I stepped away and asked the dispatcher to send CAHOOTS. The shaggy-haired, plainclothes CAHOOTS responders were able to calm him down and persuade him to get in the van, ride to the detox center, and stay there voluntarily. Decades before de-escalation became a buzzword, they de-escalated a potential police standoff or hypothermia case into a quick, voluntary van ride that hopefully started the man toward long-term recovery.

It didn’t take long for Eugene officers to start relying on CAHOOTS for social issues. Patrol got fewer and fewer calls about people experiencing drug addictions, mental health crises, or homelessness. CAHOOTS not only handled the most frustrating calls, but these responders also handled them better. Where the police presence made some people aggressive due to past negative encounters with police, CAHOOTS responders could strike up a conversation without the baggage of a badge and a uniform. They took over calls that could have ended badly for both officers and community members. The presence of CAHOOTS freed up officers to focus on the real police work they were trained to do.

Within months, it became common for officers to ask dispatch for CAHOOTS responders to take over calls where a police presence wasn’t necessary. Fellow officers even started complaining at briefings that CAHOOTS wasn’t available 24/7. Patrol officers became the strongest advocates for expanding CAHOOTS hours and putting a second van on the street.

Today, CAHOOTS responders have been taking on 911 and nonemergency police calls related to mental health, substance use, and homelessness for over three decades. The program handles about 17 percent of all Eugene Police Department calls for service.4

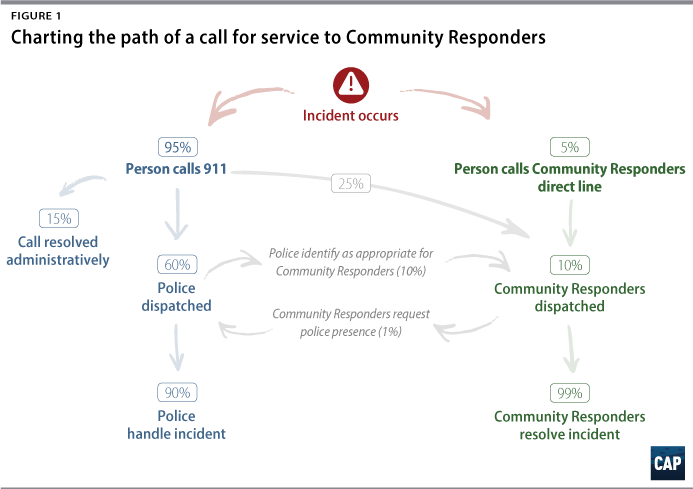

Most police officers’ first reaction to CAHOOTS is to worry that sending in civilian first responders could lead to casualties. In 30 years, the program has never had a casualty. This track record stems from excellent training for call takers and dispatchers, in addition to the CAHOOTS responders, who call for police backup in less than 1 percent of cases.5

Most officers join the police to help people and make their communities safer, but having the community’s safety on one’s shoulders can make an officer feel separate from the community. CAHOOTS shows that officers can be stronger when they accept support from community members outside the police department. It may be unfamiliar and uncomfortable, but officers need to hug the cactus.

Part III: Replicating the Model

Like pre-CAHOOTS Eugene, the Olympia Police Department in Washington was responding to the same individuals over and over. The city had few mental health resources or detox centers, so officers were facing complex cases with a toolbox of Band-Aids. Downtown businesses called the police constantly, only to have the responding officers report that they couldn’t do anything because no crime had been committed. Even when people were taken by the police to the hospital because they posed a danger to themselves or others, they were back on the street before the officers were.

The chief of police, city manager, city agencies, and community members worked together to add a new tool to the public safety belt: civilian responder teams known as the Crisis Response Unit (CRU). Two years ago, Olympia dispatchers began sending CRU to calls for service related to mental health, homelessness, or addiction with no weapons or injuries. Like CAHOOTS, dispatchers and responders are carefully trained to recognize when a situation is inappropriate, and there has never been an adverse incident.

The Olympia officers gradually saw that CRU could take frustrating, ill-suited calls off of their shoulders. Of course, veteran officers were skeptical of change, and giving away calls set off union alarm bells of “skimming work.” One supervisor openly complained that the CRU responders would just add another body at the scene that officers would end up having to protect.

But as in Eugene, attitudes in Olympia changed when officers saw CRU take over calls that they dreaded, and eventually, supervisors started to invite CRU responders to their daily briefings. At the program’s six-month survey, an originally skeptical older officer said, “I need to eat crow.” He had been responding to incidents involving the same individuals for 20 years, and he expected to keep doing it until he hung up his badge. Within six months, he saw CRU take those incidents off his plate.

Olympia has taken it a step further by addressing issues before they become 911 calls. Between calls, CRU proactively engages people on the street to preempt conflicts. When people show up on CRU’s radar several times, they can recommend the individual to a new program called Familiar Faces. The program employs peer navigators—people with lived experience with substance use and mental health disorders, homelessness, and criminal justice involvement—to build relationships with these key individuals and engage them in services.

The Familiar Faces peer navigators are able to connect with clients whom others have failed to reach because they have walked a mile in the person’s shoes. They can understand the client’s actions and needs in a way that officers cannot. The peer navigators’ personal stories can inspire clients to believe in their own recovery.

Familiar Faces navigators are also changing minds within the police department. A number of Familiar Faces team members have served years in prison, and some are currently on parole. As officers get to know them, the peer navigators are changing officers’ views about the program, their attitudes toward people with criminal records, and their willingness to collaborate to protect public safety.

Cities across the United States, as well as in other countries, are recognizing that civilian responders are part of the future of public safety. Denver’s STAR team has been responding to calls for six months and has not called for police backup once.6 San Francisco’s (California) SCRT team just hit the street in December 2020 to focus on the city’s nonemergency mental health crisis calls, which exceeded 16,000 in 2019.7 Albuquerque, New Mexico, is designing its program to address the high number of Native Americans experiencing homelessness in the city.

Each city is customizing its program to respond to local needs, but all are finding that local needs are deep. LEAP and CAP analyzed eight cities’ data and estimate that civilian responders could potentially handle 20 to 38 percent of all police calls for service.8 If the programs can reach their full potential, police can focus on their real strengths and key responsibilities.

| Table 3: Estimated Percentage of Total Calls for Service That Could Be Handled by Community Responders or Dealt with Administratively | |||

| Community Responders | Administrative alternative | Police | |

| Detroit, Michigan | 20.3% | 14.6% | 61.9% |

| Hartford, Connecticut | 25.8% | 14.8% | 58.2% |

| Minneapolis, Minnesota | 25.2% | 22.5% | 49.8% |

| New Orleans, Louisiana | 28.1% | 33.4% | 33.7% |

| Portland, Oregon | 37.8% | 29.7% | 31.2% |

| Richmond, California | 32.8% | 27.3% | 32.6% |

| Seattle, Washington | 37.7% | 25.8% | 28.6% |

| Tucson, Arizona | 24.6% | 24.4% | 44.6% |

| Table: Center for American Progress Source: The authors conducted original analysis using data from the following sources. Hartford Data, “Police Calls for Service 01012016 to Current: 2019 ANALYZED”; City of Detroit Open Data Portal, “911 Calls For Service: 2019 ANALYZED”; City of Seattle Open Data Portal, “Call Data: 2019 ANALYZED”; City of Portland Police Bureau, “Dispatched Calls for Service: 2019 ANALYZED”; City of Tucson, “Tucson Police Calls for Service – 2019 – Open Data”; City of Minneapolis, “Public 911 Call Problem Types”; City of New Orleans Open Data, “Calls for Service 2019”; City of Richmond, “RPD Calls for Service – Calls per Month, by Priority (2019-Present).” | |||

Part IV: The Future of Public Safety

The best idea can become a disaster if it’s implemented poorly. To ensure that these programs are developed responsibly, law enforcement needs to communicate their support to policymakers and other stakeholders and provide input that would make the program successful.

Instead of debating whether or not a city should bring in civilian responders, police departments and social services partners should focus on how civilian responders can best serve the city. What call types are most frustrating for officers because they know they aren’t the right responders? Which institutions generate large call volumes that could potentially be handled by civilians? (In Olympia’s case, it was transit and libraries.) What are the service gaps that create revolving doors, and which stakeholders need to sit down together to address them?

Perhaps the greatest benefit of civilian responders is giving police a chance to rebuild community trust. Every officer knows the sinking feeling when someone will not talk to us because they don’t believe that the police are there to protect and serve their community. Community-police trust has been damaged by making police responsible for handling complex social problems without the necessary tools.

This is the chance to right the ship. By handing off many social issues to trained civilians, the police can focus on serious crime and earn the community’s respect and cooperation. By supporting civilian responders, police agencies can build their strength and honor the profession. They simply need to lean in and hug that cactus.

Notes:

1S. Rebecca Nuesteter et al., Understanding Police Enforcement: A Multicity 911 Analysis (Vera Institute of Justice, 2020); Jeff Asher and Ben Horwitz, “How Do the Police Actually Spend Their Time?” New York Times, June 19. 2020.

2Amos Irwin and Betsy Pearl, “The Community Responder Model,” Center for American Progress, October 28, 2020.

3White Bird Clinic, “What Is CAHOOTS?” October 29, 2020.

4Anna V. Smith, “There’s Already an Alternative to Calling the Police,” Mother Jones, June 13, 2020.

5Smith, “There’s Already an Alternative to Calling the Police.”

6Elise Schmelzer, “Call Police for a Woman Who Is Changing Clothes in an Alley? A New Program in Denver Sends Mental Health Professionals Instead,” Denver Post, September 6, 2020.

7San Francisco Police Department, Crisis Intervention Team 2019 Annual Report, table, 2019 DEM Calls for Service (2020), 3.

8Irwin and Pearl, “The Community Responder Model.”

Please cite as

Ronnie Roberts, “Hugging the Cactus: Police Supporting Civilian 911 Responders,” Police Chief Online, April 7, 2021.