All law enforcement agencies need a headquarters or substation and will most likely need to plan, design, and build a new or renovated facility in the future.

The IACP has developed Police Facilities Planning Guidelines to empower law enforcement executives to make informed decisions and direct their facility projects to ensure the building fits the agency’s operational needs.

Since the useful life of a police facility can range from 20 to over 50 years, a new facility project is typically a first-time experience for most law enforcement executives. A law enforcement executive’s role in the process has a dramatic impact on the design, budget, use, and lifespan of a new facility. For many communities, funding for new police facilities is not available or remains at the bottom of the community’s long-term capital improvement plan. Changes in technology, building code requirements, security issues, and building system standards require significant expenditures to update, and these improvements often lack funding. Making the community aware of these issues and developing a plan of action to fix them takes significant planning.

A law enforcement executive’s role in the process has a dramatic impact on the design, budget, use, and lifespan of a new facility.

The guidelines offer a plan of action for overcoming these barriers and detail the entire process of planning, designing, and constructing a public safety facility—from gaining community and political support, to hiring an architect and conducting a space needs analysis, to debuting and occupying the facility. The guidelines also include six case studies—showcasing a variety of police facility projects that have been completed in the past 10 years.

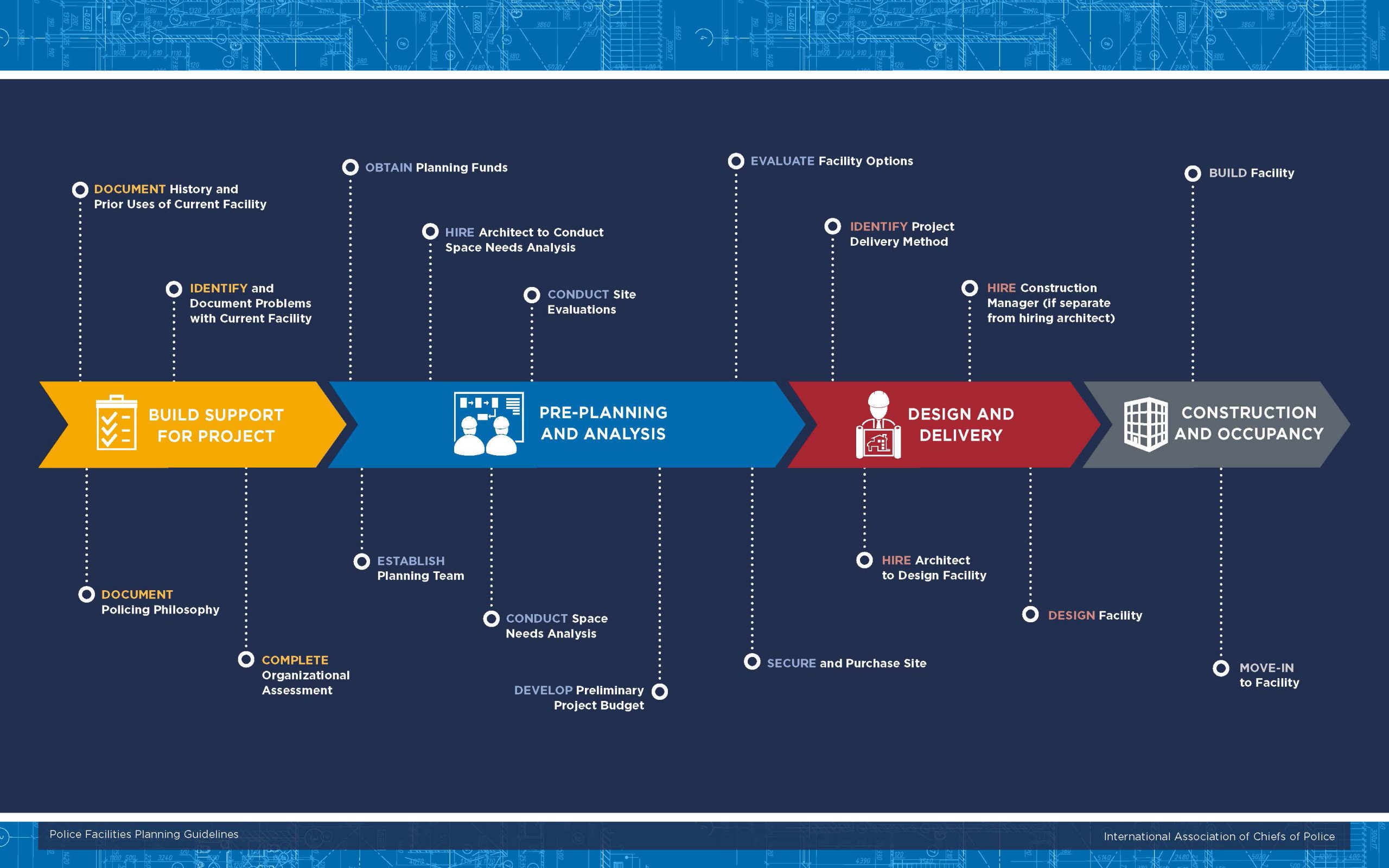

There are four key phases to any renovation, expansion, or construction and design of a new public safety facility (see Figure 1):

I. Building Support for the Project

II. Pre-Planning and Analysis

III. Project Design and Delivery

IV. Project Construction and Occupancy

(Access larger, print-friendly image.}

Phase I: Build Support for the Project

How can agencies build support for such a complex, expensive project? Understanding and articulating organizational values and philosophy is critical. Take time to review operations, processes, practices, and any aspects of the agency that the facility will impact or be impacted by. Consider questions like the following ones:

-

-

- What is the potential growth and build-out for the community, and how does this impact the staffing ratio for the police department?

- Are there areas of the organization that can be altered and reengineered to both save money and improve services?

- Are there national or local trends (legislative or cultural) that will impact personnel and space needs?

-

The Phase I section of the guidelines provides an overview of the initial information gathering and dissemination required to garner support for the project. This includes identifying and documenting uses of and problems with the current facility (operational and functional deficiencies), articulating the agency’s policing philosophy, completing an organizational assessment, establishing community and political support, and obtaining preliminary approval for the project.

Phase II: Pre-Planning and Analysis

Comprehensive pre-planning can position the project for success. This section focuses on identifying and securing necessary planning funds, establishing the planning team, hiring an architect for the space needs analysis, conducting the space needs analysis, conducting site evaluations, developing a preliminary project budget, evaluating facility options, and securing and purchasing the site. It is important to choose the right people to lead the project and to secure sufficient data and funds to guide future decision making.

Front-end planning can result in decreased maintenance costs and future renovation costs; however, law enforcement leaders should refrain from making estimates of the anticipated design and construction costs when seeking funds for the planning stage. “Ballpark” estimates at this stage are frequently wrong, since they are not based on documented information and analysis, and can become liabilities for the agency. After necessary research and front-end planning is complete, agencies should then create a project budget based on a comprehensive analysis of construction costs, such as site development and architectural costs, as well as soft costs, such as geotechnical evaluation, furniture, fixtures and equipment (FF&E), and telecommunication systems.

Phase III: Design and Delivery

This section focuses on identifying the project delivery method, including design-bid-build, design-build, construction management at risk (CMR), and integrated project delivery (IPD), as well as designing the facility. Facility design includes critical elements such as reviewing preliminary schematic design options from the architect and confirming key layout decisions. By utilizing the square footage information gathered during a needs assessment and the department needs information gathered during the organizational assessment, architects will prepare preliminary designs. This process can include gaming sessions, whereby a police planning team and architect manipulate blocks or cutouts—each labeled and representing a function or section’s relational size, such as records, evidence, locker room, roll call, visitor parking lot—attempting to find the best adjacency fit that meets a department’s needs, as well as any present site constraints. This is a very hands-on approach and allows a police planning team to be thoroughly involved in the process and discuss the realities of site constraints, functional area size, adjacency relationships, and security.

Find ways to engage the community in the process and keep them apprised of how the facility project is progressing.

Throughout the design phase, it is important to keep all relevant stakeholders involved. The same is true for the community. Find ways to engage the community in the process and keep them apprised of how the facility project is progressing.

Phase IV: Construction and Occupancy

The guidelines also focus on building the facility, moving into and occupying the facility, and capitalizing on community engagement opportunities. Construction times vary depending on the size and scope of a project; schedule; and natural or imposed delays, such as weather, difficulty obtaining specific materials, or other variables. It is vital to select a contractor, CMR, or design-build entity that has a good track record of delivering facilities on time and within budget. Further, a clear and well-designed transition to occupancy plan is required. Employee satisfaction with a new facility is affected by the manner in which the transition to occupancy is carried out. Confusion, loss of information, and other transitional problems can negatively impact staff morale.

Conclusion

Planning, designing, and constructing a police facility takes a tremendous amount of time, effort, communication, and commitment. While some projects are completed within two years, others might take a decade. Commitment to the project and consistent communication between all stakeholders, including city officials, agency employees, and community members, are critical to the overall success of the project. With adequate planning and a commitment to the organizational policing philosophy, a new or renovated facility can do more than address deficiencies and inefficiencies—it can position the department to deliver new and improved services that were not previously possible. While the architectural team should include public safety facility experts, only the law enforcement executives and police planning team can develop and relay the long-term goals and needs that the facility must satisfy.

For more information, please visit theIACP.org/PoliceFacilities. |