Imagine that you are the chief of a large municipal police department with more than 500 sworn officers. To improve efficiency, your agency has arranged for a single patrol officer to take one-half of the city’s property crime reports. The officer involved is a veteran whose sole concern is getting offenses documented in your records management system (RMS). At the point of first contact with each victim, the officer sternly warns that filing a false police report is a felony and could result in fines or imprisonment. The officer proceeds to interview the victim, asking more than 50 forced-choice questions, many of which are poorly worded, redundant, or not applicable to the given situation. If the victim gets confused and asks for clarification, the officer simply ignores them until they provide an answer. At no time does the officer acknowledge that this event might have been upsetting for the victim—the only objective is to get the required details and move on to the next case. Accordingly, if the victim takes more than 30 minutes, the officer abruptly terminates the interview, shreds the report, and drives away. The victim has to decide whether to restart the process by calling 911 again or just forget about the whole thing. Even when a victim successfully completes their report, they almost never hear back from the agency, leaving many to question the value of calling the police.

Anyone working in leadership today will recognize this scenario as a problem if the agency hopes to maintain or improve community-police relations. Public trust in law enforcement has declined in recent years, particularly among certain demographic groups.1 This makes it more difficult for police to engage the public in crime prevention, and it may contribute to some people breaking the law.2 In an effort to increase legitimacy, agencies are being advised to incorporate procedural justice into their interactions with the public.3 Officers should convey trustworthy motives, treat people with respect, grant community members a “voice,” and be neutral and transparent when making decisions.

Most of the focus to date has been procedural justice training for officer-initiated contacts (e.g., traffic stops, pedestrian stops, investigations, and arrests). Less attention has been paid to how officers interact with victims who contact the police for assistance. This is unfortunate from several perspectives. First, victims account for a substantial proportion of an officer’s public contacts. Second, victims may have more trust to lose. They would not have reported the crime if they did not have some degree of confidence in the agency. Third, victimization often leads to decreased satisfaction with law enforcement.4 This may result from people holding the police partly accountable for their victimization, having unrealistic expectations for what the police can do, or experiencing a negative interaction with the responding officer(s). Finally, crime reporting is critical to the functioning of the justice system, and the police should do everything possible to encourage the reporting of crimes.

Victims’ decisions to not call the police may fundamentally shape our understanding of the distribution of crimes, limit the protective and emotional support received by victims, undercut the deterrence capacity of the criminal justice system, and hamper scientific evaluation of policies directed at improving public safety.5

It seems likely, therefore, that most police administrators would directly intervene in the imagined crime reporting scenario from above. They would require either a change in the dispatch protocol or, at a minimum, significant retraining for the officer involved. To do otherwise risks losing too much.

Unfortunately, as documented herein, the hypothetical situation depicted above is very real for many agencies. However, rather than a single officer who takes 50 percent of their reports, departments have adopted online crime reporting systems that function similarly. Victims are referred to the agency’s website for lower-severity offenses as opposed to interacting directly with an officer. Once victims arrive at the site, they are usually faced with a warning that filing a false report is a crime. Victims are then left to navigate a complex records management system with limited to no user support. If people take too much time to complete the reporting process, the system might lock them out and force them to start over. And, like the scenario above, people rarely hear back from the agency if (or when) their reports are finally submitted.

Online Crime Reporting Research

The authors’ interest in online reporting evolved out of a Community-Based Crime Reduction (CBCR) grant from the U.S. Bureau of Justice Assistance. The original plan for the grant involved having officers do in-person follow-up visits with property crime victims to build relations with local residents and encourage prevention measures (e.g., exterior lights, cameras, and steering wheel locks). The combination of Covid-19 and significantly reduced staffing led the researchers to pivot and focus on victims using the Portland, Oregon, Police Bureau’s (PPB) online crime reporting system. An unpublished study by the National Police Foundation in 2019 found that victims using the PPB’s online system were significantly less satisfied than people who reported directly to an officer.6 This finding was worrying given the city’s ongoing federal mandate to improve local community-policing relations, rising crime rates, and the city’s increasing reliance on this type of reporting.7 Online reporting currently accounts for 48 percent of the city’s property crime and 39 percent of all incident reports.

Upon seeking additional guidance, the authors found an astonishing lack of studies or even substantive discussions of online reporting and its impacts. This dearth of information led the authors to conduct their own research on the topic. Over the past two years the grant team carried out several research studies to see what could be learned about online reporting and how to improve it. The following summarizes the findings as they relate to four key research questions (RQs).

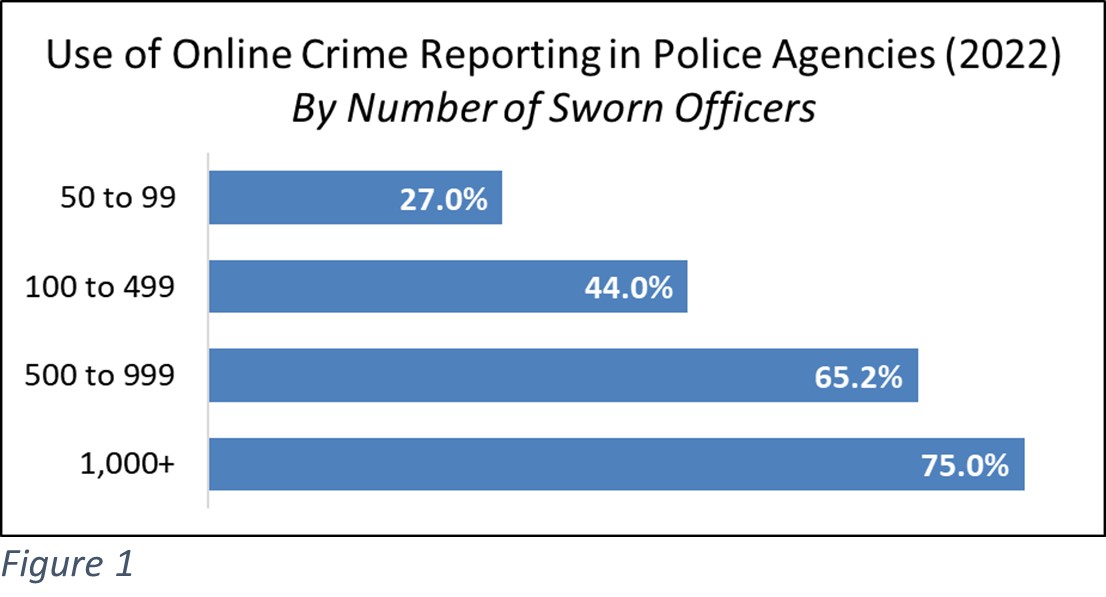

RQ 1. How many police agencies offer online reporting?

Two waves of the Law Enforcement Management and Administrative Statistics survey (2013 and 2016) were used to identify a sample of 975 U.S. municipal police departments with 50 or more sworn officers.8 This includes almost all agencies with 100+ officers and a random selection of smaller departments. The research team then reviewed each agency’s website to determine whether they offered online crime reporting at the start of 2022. The results are provided in Figure 1. Nearly one-half (40.1 percent) of all agencies had online reporting and the rate of use was considerably higher among larger agencies. The availability of online reporting appears to have increased over time and is more common among agencies in the western United States, those with higher violent crime rates, and those with a lower ratio of officers to city residents. The latter finding suggests that the decision to adopt online reporting is being driven, at least in part, by resource strain.

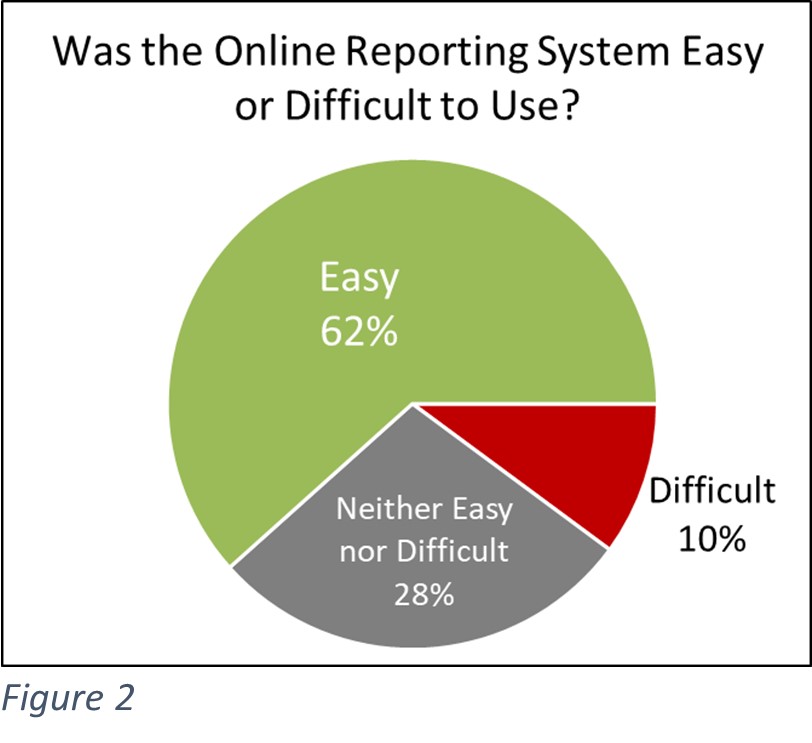

RQ2. How do victims feel about the online reporting system?

More than 1,200 victims in Portland were surveyed about their experience with the PPB’s online reporting system. On the positive side, most people report that the system was easy to use (see Figure 2). Convenience, conserving agency resources for more serious crimes, documentation accuracy, and avoiding negative interactions with officers were the most commonly cited benefits of online reporting. On the negative side, one in ten victims said the PPB’s system was difficult to use. Given that only people who completed their report were included in the survey, it is suspected that the actual number of victims having trouble with the system is probably higher.

Victim complaints about the PPB’s online system centered on technical issues with the vendor’s user interface, including mobile phone incompatibility, system time-outs, and forced responding. Others complained about inadequate instructions, a lack of user support once the report is started, uncertainty about the correct response options, time-consuming and redundant data entry, and difficulties updating reports after they are submitted. Notably, people reporting difficulties with the online system were more than twice as likely to be dissatisfied with the PPB’s overall handling of their case.

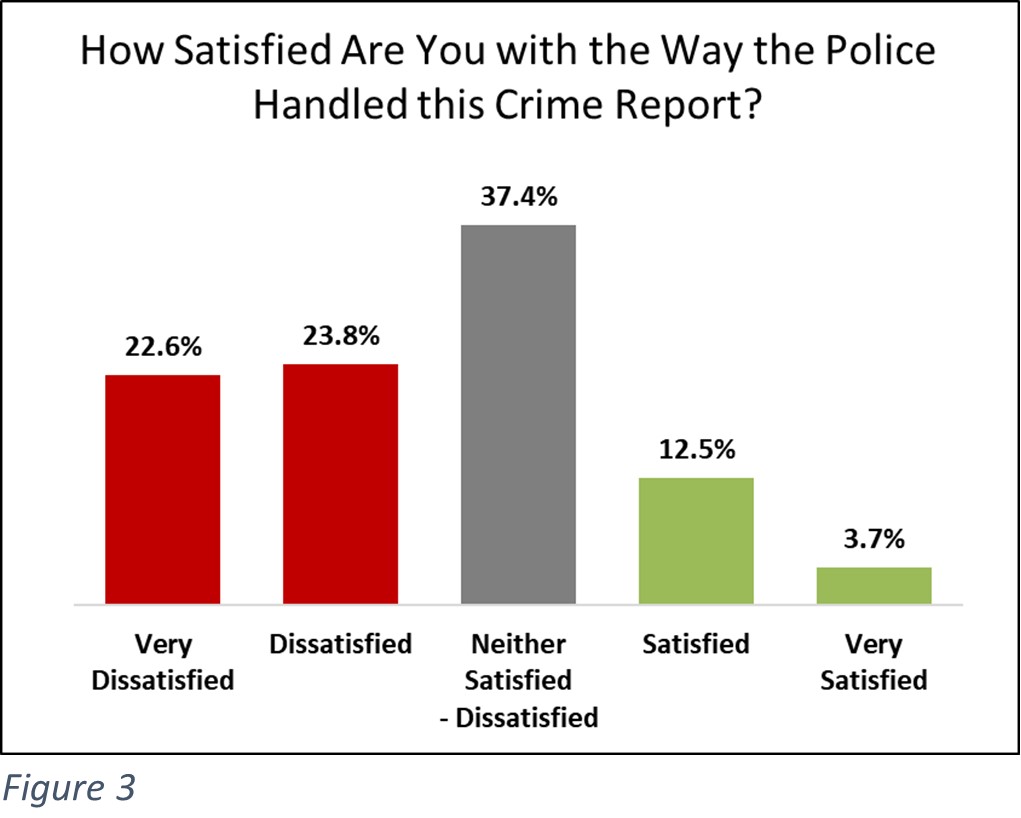

RQ 3. How do victims feel about the police department’s response to their online report?

Only 16 percent of the respondents surveyed said they were satisfied or very satisfied with the way their online report was handled by the police (see Figure 3). The remaining victims were asked what the agency could have done to make this a better experience, and the number one suggestion by far was to provide some type of follow-up after the initial report was submitted, as evidenced by the following responses:

- Respond in any way at all. Phone call, email, text, smoke signal. ANYTHING.

- Get in contact with me about the incident; no one ever tried to call or email me about it.

- It would be great to speak to a person, or any kind of response afterward.

- An actual phone call, even if the officer cannot appear in person.

Other suggestions included investigating the incident, taking steps to reduce crime, informing the public about the agency’s crime prevention efforts, and checking to see if the victim was all right.

RQ 4. Can victim satisfaction with online reporting be improved?

The short answer is YES, absolutely. This answer was tested by using some of the CBCR grant funds to pay officers overtime to provide follow-up contacts to online reports. Victims in 16 Portland neighborhoods received a personalized phone call, voicemail, or email three weeks after filing an online report. The officers used communication scripts incorporating concepts of procedural justice (e.g., listen to the victim, communicate concern, validate their emotional response, and answer questions). To help manage expectations, officers discussed the difficulty of solving property crimes and then pivoted to sharing crime prevention tips.

Victims were usually grateful for the outreach delivered.

- Thank you so much for reaching out, both on the phone and via email. It means a lot!

- Thank you. We appreciate you and value what you do for the community to keep us safe.

- Oh my gosh, I was so impressed that [the officer] not only emailed me but also called. This is the first time I have received a call about one of my online reports. Good job with the change in the protocol because it will change perceptions about police.

This appreciation was similarly reflected in the objective data from the surveys. Compared to victims in six control neighborhoods, those in the target neighborhoods who received the outreach were significantly more likely to be satisfied with the PPB’s handling of their incident report (12 percent vs. 43 percent). Those in the target neighborhoods also had greater confidence in the agency and higher trust in local law enforcement.

Summary and Recommendations

There is a long history in U.S. policing of incorporating new technology with the goal of increasing operational efficiency and effectiveness. There is also evidence that these objectives are not always achieved in equal measures; improving the former is often easier than improving the latter.9 Moreover, technical innovations often have unanticipated consequences that may outweigh any benefits derived. The research presented suggests that online reporting runs the same risk. Agencies are likely to save considerable resources when shifting from in-person to online reporting (i.e., they win one battle), but this may come at the cost of lower public trust and confidence (i.e., they lose the war).

Additionally, very little is known about the impact of online reporting on police officers. What happens when their easier calls are taken away, and they are left to deal with the most complex, often violent incidents? How do officers stay abreast of crime in their patrol area when a large proportion of incidents are reported online? Similarly, it seems reasonable to question the impact of online reporting on the quality of data obtained. Most of the recent advances in proactive policing rely on access to and analysis of criminal incident data (e.g., hot spot policing, intelligence-led policing, focused deterrence, and problem-oriented policing).10 Does the quality of data generated from online reports differ from data communicated in person from victims to officers? It is also unclear whether the online systems currently used are fully compliant with NIBRS reporting standards.11

With nearly one-half of larger agencies in the United States already using online reporting, however, the time for carefully weighing the pros and cons of this technology has probably passed. Instead, it may be more useful to focus on making online reporting a better experience for victims and seeking to mitigate any harm done to community-police relations when agencies adopt or expand their use of online reporting. The research in Portland led to the following five recommendations to achieve these objectives:

- Educate community members about online reporting.

Fifty years of the 911 emergency response system have trained U.S. residents to expect the timely arrival of an officer when they report a crime. Shifting some, possibly a majority, of these calls to an online reporting system will not be universally appreciated in the community. Police departments may be able to limit some of this dissatisfaction by proactively communicating with the public when they add or expand this type of reporting. One “framing” option focuses on the potential benefits of reporting crime online. The community as a whole might benefit because the agency will have additional resources to address more serious incidents. Victims benefit from the added convenience of online reporting because they will have time to carefully document all of the property items involved. Another advantage concerns people or communities who might be intimidated by direct interaction with a police officer. Focusing on benefits like these might make the transition from in-person reporting to online slightly more palatable for people in the jurisdiction.

- Improve the agency’s landing page.

Agencies typically use a vendor for documenting criminal incidents and link to the online platform via a landing page on their website. These pages are often quite anemic, doing little more than warning people about filing a false report and listing the applicable offenses. This represents a lost opportunity for communicating strategically with victims to enhance trust. Consider adding text or a video message that accomplishes the following: (1) communicates concern and acknowledge the harm done to the victim; (2) thanks the victim for reporting the crime and explain how the agency uses these data; (3) prepares the victim for entering the online system and explains why so many questions are asked (i.e., FBI reporting standards); and (4) helps to manage expectations by informing the victim about what happens after a report is filed. If no follow-up is likely, then say this and explain why.

- Provide user support.

Most victims accessing the online system have no prior experience with crime reporting. Many are emotionally distressed about their recent victimization, or they are nervous following the warning about false reports. Others have limited computer skills and are worried about pressing the wrong button. Expecting all of these people to independently navigate a complex crime reporting system seems unrealistic, if not downright unkind. At the very least, agencies should provide victims with basic instructions before they enter the online platform. A reasonable accompaniment is to provide “live” phone support in case users run into problems after entering the online system. Finally, a lot of the problems reported in the surveys had to do with the vendor’s software. Encouraging vendors to improve these systems and incorporate context-specific guidance would be a huge win for everyone.

- Deliver some type of follow-up.

The surveys in this study have clearly shown that most people expect some type of follow-up when they submit an online report. Sending an automated email with a final report number for insurance purposes is not enough if the goal is to maintain or improve community satisfaction with the agency. In the current research, officers were paid overtime to conduct personalized outreach. But it seems likely that the benefits observed might also be obtained using non-sworn personnel, police trainees, or appropriately supervised volunteers.

- Assess victim satisfaction and adjust accordingly.

The benefits of adding or expanding online reporting tend to be readily apparent. The agency’s calls for service involving the dispatch of an officer will probably decline noticeably. The potential harm of adding or expanding online reporting, however, is often less tangible. Police agencies rarely have a standardized protocol for monitoring victim satisfaction. Fortunately, this is easily rectified with online reporting. The software usually requires a valid email address and cellphone number. This makes it easy to conduct follow-up surveys with victims using the online system. Once a survey is in place and a baseline is established, it can be used to evaluate the impact of changes made to increase victim satisfaction.

Notes:

1Jeffrey M. Jones, “Confidence in U.S. Institutions Down; Average at New Low,” Gallup, July 5, 2022.

2Tom R. Tyler, Why People Obey the Law (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2006).

3Final Report of President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing (Washington, DC: Office of Community Oriented Policing Services, 2015).

4Michelle A. Bolger, Daniel J. Lytle, and P. Colin Boulger,”What Matters in Citizen Satisfaction with Police: A Meta-Analysis,” Journal of Criminal Justice 72 (January–February 2021), 101760.

5Min Xie and Eric P. Baumer, “Crime Victims’ Decisions to Call the Police: Past Research and New Directions,” Annual Review of Criminology 2 (January 2019): 217–240.

6National Police Foundation, Perceptions of Portland Police Bureau among Persons with a Recent Police Contact: Results of an SMS Survey (Portland, OR: Portland Police Bureau, 2019).

7U.S. Department of Justice, Civil Rights Division, Findings Letter – Investigation of the Portland Police Bureau (Washington, DC: Civil Rights Division, 20120.

8Bureau of Justice Statistics, Law Enforcement Administration and Management Statistics, 2013, 2016.

9Cynthia Lum, Christopher S. Koper, and James Willis, “Understanding the Limits of Technology’s Impact on Police Effectiveness,” Police Quarterly 20, no. 2 (June 2017): 135–163. See also Christopher S. Koper, Cynthia Lum, and James J. Willis, “Optimizing the Use of Technology in Policing: Results and Implications from a Multi-Site Study of the Social, Organizational, and Behavioural Aspects of Implementing Police Technologies,” Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice 8, no. 2 (June 2014): 212–221.

10National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, Proactive Policing: Effects on Crime and Communities (Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2018).

11One issue that the researchers found with the software used by PPB is that victims can report only one crime at a time. One of the benefits of NIBRS is that it supports reporting multiple offenses per criminal incident.

Please cite as

Kris Henning et al., “The Impact of Online Crime Reporting on Community Trust,” Police Chief Online, April 12, 2023.