Intelligence-led policing (ILP) has resulted in police operational decisions becoming increasingly data driven, and many communities are safer because police departments analyze incident data more effectively and assign their resources more efficiently than they did in the past. Intelligence-led promotional decisions could also have a positive impact on police safety and effectiveness. A data-driven leader selection process can help better fulfill the community’s expectations, engage officers, and identify leaders without discriminating among candidates based on gender, race, or ethnicity.

“Providing leadership opportunities equally to all applicants is critical.”

Reduced officer morale and the inability to select key supervisors have significant impacts on a department’s abilities to recruit officers and to contribute to community members’ sense of personal safety. As is true across virtually all industries, some of the greatest job stresses police officers experience are caused by ineffective supervisors.1 Police departments that better select and train managers can enjoy a strong advantage when competing with other communities for residents, employers, and officers. Employee turnover, low productivity, and litigation are costly, and a metrics-driven system for training and developing managers can return more to the department than just the money saved.

Studies spanning 20 years with police departments that sought to improve their leader selection examined the effects of data- and metrics-driven selection processes on the agencies’ leadership.

Focusing on the Team’s Performance

For an effective study to be conducted, the first task was to define “leadership” in a way that was verifiable and that reflected the values of the departments. Senior police managers recognized that the core task of the effective leader is to build a team that performs better than its competitors in similar departments. Rather than defining “leadership” as simply achieving a higher rank, leader effectiveness was defined as the ability to build a team that was fully engaged, offered extra discretionary effort, and fulfilled the organization’s expectations. High-performing teams serve community members who become safer and feel more secure. These teams experience lower turnover and are sought after by recruits and lateral transfers. Members of high-performing law enforcement teams are proud of their membership on that team and give extra effort to the team’s mission.

A critical step in improving leader selection is to recognize the limitations of common promotional processes. Decades of data are convincing: Half of all managers worldwide and across industries are ineffective in their roles. That finding holds across both private and public employers and across a variety of methods for measuring leader performance.2

Selecting leaders is a high-risk activity for any police agency. It takes a good leader one to two years to improve the performance of a team, while a poor leader can hamper a team’s effort almost immediately. Officers in disengaged teams withhold effort and leave the team as soon as opportunities allow. No program, department culture, or motivational effort can be successful when good officers become discouraged by poor supervision. Employee engagement predicts virtually all significant organizational outcomes, and therefore predicts the ability of the department to compete with other departments for talent and resources.3

Undetected Risks

One of any promotional team’s greatest challenges is to identify risks that a candidate has been able to control when he or she was closely supervised. Some of the risks that derail leaders are former strengths taken to an undesirable level, so identifying competencies is only half the job. Police departments usually assess the promotional candidate’s talents, focusing on experience and skills, past job performance, supervisor recommendations, panel interviews, and assessment scores. If departments use formal testing at all, they use tests of psychopathology or of the individual’s strengths and technical skills. Unfortunately, the best and worst supervisors likely both have the competencies necessary for the job and do not exhibit true psychopathology. Officers’ frustrations are more often linked to supervisor’s candor that has turned offensive, consistency that became petty rigidity, conscientiousness grown to micromanaging, and blind loyalty to senior managers leading to failure to support their subordinates. With the increased discretion that would come with the new role, confidence can turn to arrogance, a sense of urgency leads to overreaction, the careful person becomes a second-guesser, and the go-getter has trouble delegating.

Instincts vs. “The Numbers”

There is a significant hurdle to overcome when trying to adopt intelligence-led advancement (ILA). Senior managers and members of police commissions often believe that their own judgment is sufficient to make good promotional decisions. As seen with ILP, numerical models of reducing risk and allocating resources consistently outperform the decisions made by individual experts. Numerical models of leader selection designed by the department are likely to result in more effective teams when there are closed feedback loops regarding the job performances of promoted individuals.4

Another challenge is convincing senior managers to allow promotions to be strongly guided by the objective data they have selected. Too often, senior managers prefer to follow their “gut” about whom to promote without analyzing the factors that support their instincts. The best response to that reluctance is to show promotion decision-makers that their judgments are integrated into the ILA process. Their experience helps form the performance criteria selected, so their knowledge is not lost among “the numbers.”

“In addition to reducing subjective bias in promotions, the scored interviews and testing algorithm help analyze the closed feedback loop, allowing the department to continually improve the promotion process.”

As with any rigorous process, some agencies adopt intelligence-led language but not the actual tasks involved. They use data to justify rather than to drive their decisions. Unless they truly close the feedback loop by measuring the ultimate performance of the new leader, they are not likely to improve their organization’s performance.

Current promotional processes often strive to be broadly inclusive in who is invited to contribute to the decision. Involving a greater variety of people ensures some transparency and buy-in. In today’s climate, it is also an opportunity to involve community members. A more inclusive process alone, however, will not be sufficient for distinguishing between effective leaders (those whose teams consistently perform well against the competition) and those individuals whose greatest skills are to relate well with senior managers and to get promoted.5

The product of the current promotional processes is that at least half of the selected candidates across industries are ineffective in their new roles. Unless an agency examines promoted individuals’ subsequent job performance, it cannot improve its selection processes. In addition, there needs to be a credible alternative and desirable career path for a promoted candidate who ultimately proves not to be a good team leader. Otherwise, senior commanders will be reluctant to replace a less-than-effective supervisor. The result of ineffective leadership extends beyond negative impacts on team performance to negative impacts on team health outcomes.6

Targets and Tools

Evaluating the wisdom of promotions requires focusing on measurable qualities of effective leaders. The following five criteria were selected for the research and for the examples below: (1) initiative, (2) integrity, (3) persistence, (4) vision, and (5) team commitment. Targeting these specific qualities and how they can be measured also provide a way to assess subsequent progress on the job. Specific rank was not included as a measure of effectiveness in the studies discussed. A high-performing, fully engaged patrol shift is more likely to have an effective leader than is a squabbling senior management group.

Tools used to measure these five qualities included 360-degree questionnaires (made anonymous to avoid their being used outside the research); in-depth interviews about the supervisors with the chief; objective testing of leadership strengths and risks; nominations by peers, supervisors, and subordinates; and whether or not the supervisors were promoted over a 15-year period. In the 1999 project, objective measures of emotional or mental health problems and overall problem-solving abilities were also included. Mental health and problem-solving measures were not included in subsequent research because in the 1999 sample there were no significant differences in those test scores between effective and ineffective law enforcement leaders. Substantial differences between effective and ineffective leaders were seen with the other objective measures.7

In the 1999 sample, all officers and supervisors in the department were given nine brief scenarios and asked to nominate two current supervisors who would perform best in those situations. Three of the nine items were “lead a task force for department improvement,” “take disciplinary action against an officer,” and “be approached by an officer in personal distress.” Using only objective test results as the selection criterion, 11 of the 12 department supervisors were correctly identified as being in either the more or less effective groups, as had been assigned according to colleagues’ judgments.

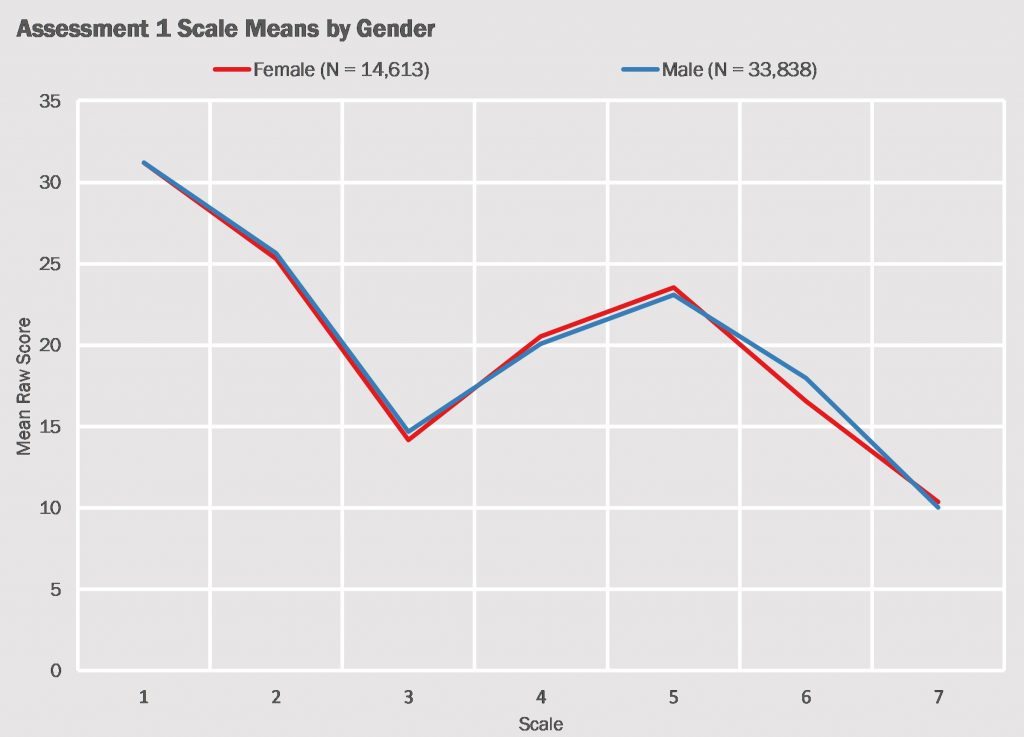

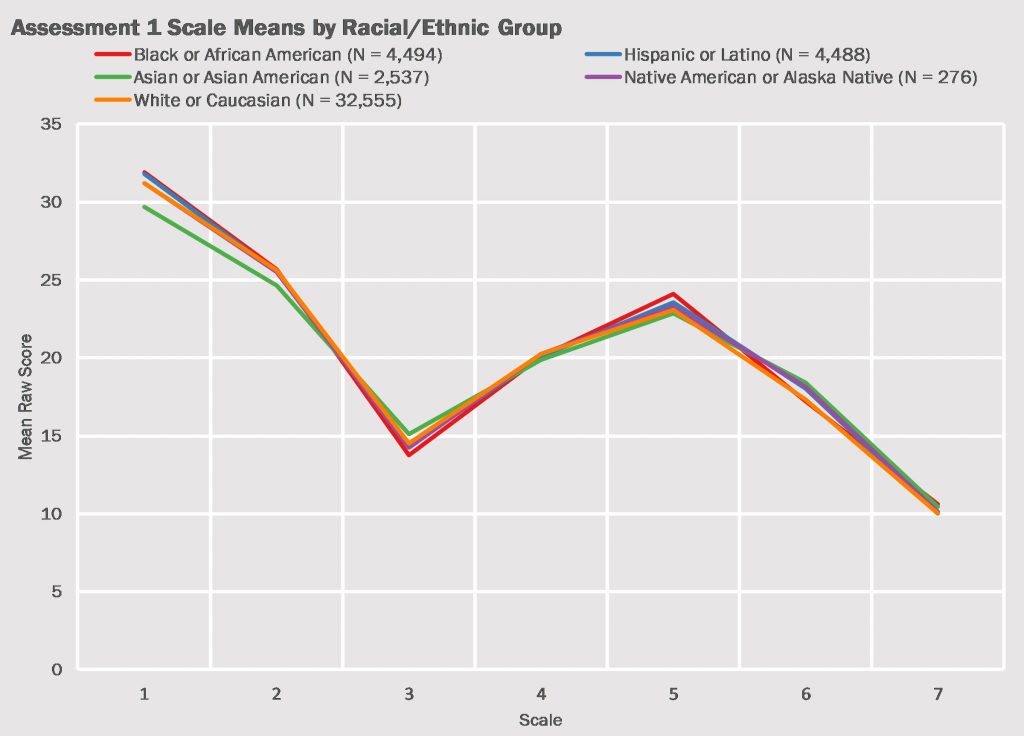

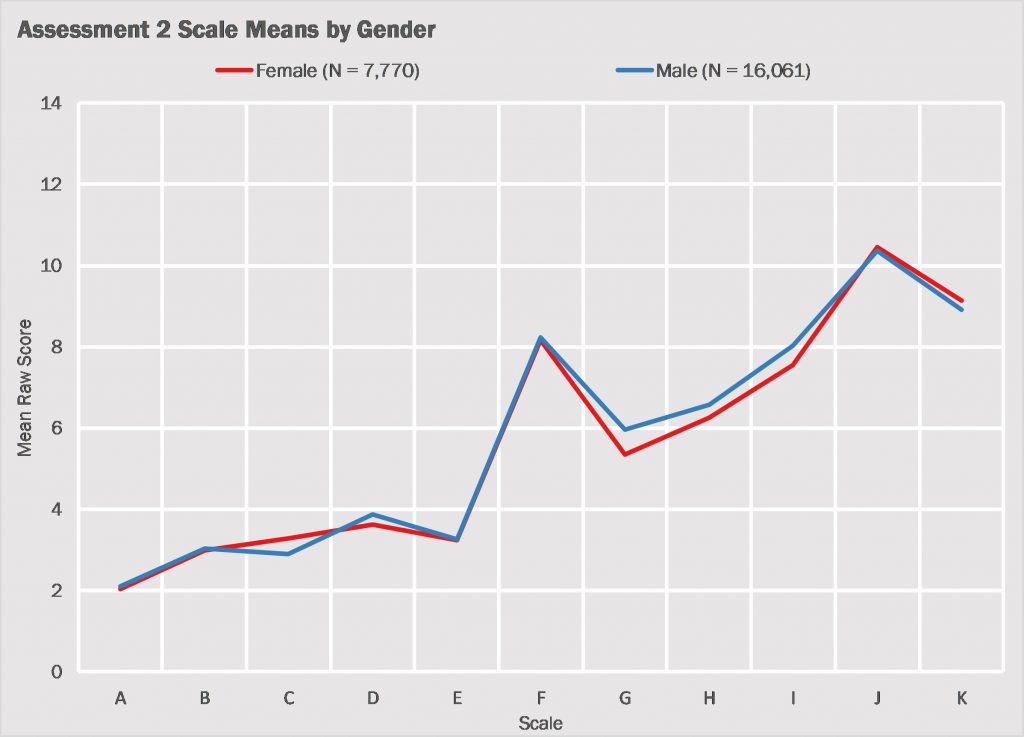

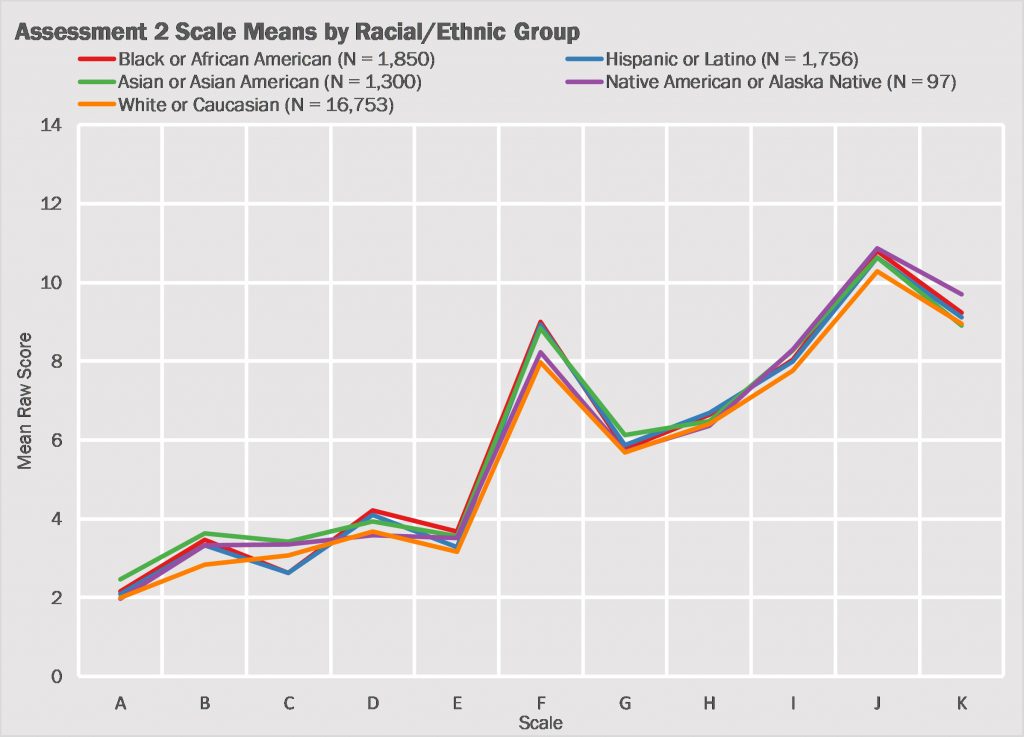

Providing leadership opportunities equally to all applicants is critical. Decades of research demonstrate that scores on the tests of leadership qualities used in this research are no different across gender, racial, or ethnic samples. The “everyday” and “risk” test components seen in Figures 1–4 were combined to create the algorithm. All components of leader selection processes should have demonstrated their lack of adverse impact on minority candidates.

|

Figure 1  |

Figure 2  |

|

Figure 3

|

Figure 4  |

The riskiest leader selection procedure is one that is not later verified by the job performance of newly promoted individuals. Police agencies naturally wish each new promotion to be successful and are reluctant to remove a promoted individual from the new role. Removal of a supervisor because of less-than-expected job performance, even if doing so would benefit the team, could have a negative impact on that person’s career. A better outcome in the case of poor performance by the newly promoted officer (after a reasonable time period of on-boarding and training) would be a different assignment that more closely fits the individual’s talents. Departments whose newly promoted supervisors nearly always either remain in those positions or are subsequently promoted again are likely to have a significant number of ineffective supervisors.8

Research Results

The following data results from six group samples of police leaders and three illustrations comparing individual leaders. The predictive measures were either an algorithm based on objective tests of leadership qualities or 360-degree questionnaires completed by colleagues of the leaders. Police leaders were sorted into more effective and less effective groups using whether they were or were not promoted or through nominations by colleagues or the police chief.

The algorithm was built by comparing police leaders’ objective test scores with their on-the job performance. Approximately 440 combinations of test scores were identified. Those score combinations were then revised after being compared with eight different samples of technical and supervisory employees from a variety of professions, including law enforcement. Subject leaders’ job performances were verified by their employers. Individual weights were assigned to score combinations in order to achieve optimal sorting of more effective and less effective leaders. The resulting algorithm includes more than 1,200 individuals.

Sample 1 involved 36 police leaders from three different departments. Leaders were sorted into “more effective” and “less effective” groups after in-depth interviews with the agencies’ chief. The interviews with the chiefs were extensive to help separate more effective and less effective supervisors according to goal achievement and team engagement rather than according to the personal preferences of the chiefs. The target leadership dimensions were whether the individual being considered was leading a team that was achieving expectations and was engaged with the department as seen in their offering discretionary effort to the department’s mission. Algorithm scores were calculated from the test results obtained by the officers at the time of applying for the leadership positions. Algorithm scores for those judged “more effective” averaged at the 68th percentile while scores for those judged “less effective” were at the 28th percentile.

The second sample (N=46) was within one police department, and the single criterion for comparison was whether the individual had been promoted in the past 17 years. Those officers who were promoted during that period had algorithm scores averaging at the 71st percentile, and those not promoted had an average algorithm score at the 42nd percentile.

Sample 3 included 34 police lieutenants from a single department. On average, those described by the police chief as more effective had algorithm scores averaging at the 68th percentile and those judged less effective averaged at the 27th percentile. Figure 5 illustrates the efficiency of the algorithm in three pooled departments from two different regions of the United States. While the algorithm worked well for these organizations, all selection methods should be tested for effectiveness by the local department.

|

Figure 5  |

Sample 4 (N=192) was not sorted between more and less effective. Instead, it was used as a way to understand how that sample of police leaders scored on the five different components of the algorithm (initiative, integrity, persistence, vision, and team commitment). It is common for law enforcement officers and leaders to score highest on integrity and persistence compared with individuals from other professions. The same was true for this sample, who as a group scored higher on integrity and persistence, but not as high as other professions on engagement and team commitment. In other words, this and other samples indicate that police leaders are often trustworthy and dedicated but do not manage purpose, priorities, or interactions as well as leaders in other professions. Too often, police leaders who target purpose, values, and interactions are seen as “soft,” despite the importance of those factors to team performance.

Sample 5 was 75 police leaders who usually operated as independent contributors, preferring to work individually on high-priority cases rather than as true team leaders. Their highest algorithm scores were on vision (carefully selecting among priorities) and lowest on team commitment (interacting with community members and colleagues).

To test the question of police leader qualities with other data, each of 58 law enforcement leaders in an executive training institution asked at least 10 of their colleagues to complete a 360-degree evaluation. The questionnaire evaluated the same leader qualities as the algorithm. Through their responses to the 360-degree questionnaires, the leaders’ colleagues indicated that, as a group, the leaders demonstrated integrity. They scored lowest on vision (setting priorities, communicating a sense of purpose) and team commitment (engaging officers, successfully managing interactions with officers).

Individual Comparisons

Objective testing can also help understand problems within teams. For example, two senior managers were highly technically skilled, and both had long police experience. One was a true team leader (algorithm score at the 92nd percentile) while the other much preferred to work alone (algorithm score at the 3rd percentile). Their work together was hampered by the individual contributor failing to communicate about his work and often canceling planning meetings. In the end, both of their job performances suffered.

“Chosen tests should address both everyday work habits and potentially negative qualities that emerge only under pressure or when the individual feels comfortable to use complete discretion.”

In another example, two candidates were seeking to transfer from one department to another—an officer and a lieutenant. The lieutenant was assessed first. The lieutenant’s interview was poor, and his algorithm score was at the 2nd percentile. The lieutenant’s strengths from the point of view of the objective testing were that he had a sense of urgency (that could easily escalate into overreaction) and strong sense of loyalty to senior managers. He had difficulty making decisions, often second-guessed himself and other people, and habitually micromanaged. The lieutenant performed at an exemplary level on a test of problem-solving ability. He was not recommended to join the new department. The officer was assessed a week later. He was fully qualified and recommended. At the end of the officer’s interview, he said to the examiner, “I heard that you might have been part of the decision about whether to bring in the lieutenant. He did not get the position. I know you won’t tell me, but if that was you, good job.” The Lieutenant candidate had the experience and the rank to make him qualified for the job, but a 90-minute job-related interview, objective testing and a current colleague all agreed that he was a poor fit.

Candidate Interviews

Promotional recommendations require well-researched tests and comprehensive interviews. The best testing systems examine both how the individual approaches work customarily as well as how the person changes when under pressure or when given greater discretion, as in supervisory positions. A semi-structured interview allows the examiners to understand what the candidate has learned and how well the person can communicate those lessons. In one case, three candidates for police chief were assessed for an agency whose police commission had stated clearly that they were looking to achieve a “turn-around” for the department. One of the candidates was internal and, due to his experience, should have had an advantage. However, he was easily disappointed with officers he supervised and saw his job as “trying to keep the lid on.” The internal candidate had an algorithm score at the 22nd percentile. The external candidate with the highest algorithm score (91st percentile), however, produced an unusual interview. Throughout the nearly two-hour job-related conversation, the candidate never mentioned crime prevention or intervention, accountability, increasing community members’ perception of safety, or any other topic that most selectors would expect of a police chief candidate. Had the interview been recorded, most people would not be able to detect that the person was applying for a law enforcement position. The individual who was named to the position (algorithm score at the 70th percentile) said early in the interview, “My first job is to reduce crime and to make sure that citizens feel safer.”

The best kinds of interviews are those whose initial questions are identical for each candidate for a position. That consistency allows for review of the selected candidate’s interview answers after the person’s job performance is known. Interviews work better if most questions have a “dropdown menu” that gives the examiners a chance to look more deeply into an answer. For example, after listening to a candidate’s description of a typical workday, the examiner can ask about tasks or projects that the candidate would often like to pursue, but does not have enough time to do so. As examiners complete feedback loops with hired leaders, it will become clear that the more specific the candidate’s answer to a question and the more often the candidate provides a detailed example as an answer, the more effective that person will prove to be after hiring. High-minded, well-articulated answers that address only general principles often are provided by leaders whom the team members will learn not to trust. Some candidates require reminding more than once in an interview to provide specific responses from their own experience. Requiring those reminders can be a sign that the person is not ready for the position.

Hypothetical scenarios are useful if they are clearly defined. For example, “Let’s say that you have an officer who has performed very well over a long period of time. Lately, the officer’s performance has suddenly deteriorated. The individual is crabby and does not get the work done. You have tried to speak with the individual about it, but you were brushed off. What do you do?” The best candidates understand immediately that the former stellar officer is probably experiencing a personal crisis. The officer is forgiven for the less-than-diplomatic response to the inquiry. Instead, the candidate will say to the officer, “This is not like you. You have been valued by everyone here for how you do your work and how you relate to us. Let’s go get a cup of coffee. I want to understand how I can help you get back to where you have always been.” Less-qualified candidates are put off by the officer’s initial rejection or believe that they need to consider progressive discipline. They do not describe how they would discover the officer’s problem.

Interview answers can be scored 0, 1, and 2, with a 2+ for an exemplary answer. Semi-structured interviews usually require 60–90 minutes. The examiners ask only initial and follow-up questions. Some of the least effective promotion interviews are rambling conversations whose ultimate effectiveness would be difficult to assess.

Destructive Biases

Many police chiefs are currently asking about detecting bias in potential candidates. Implicit bias about gender and race is universal. Humans evolved in groups whose safety was impacted by the group’s ability to separate “us vs. them.” However, by now, everyone should know that there are many more similarities among people than differences, and those differences that exist are part of the richness of life. Bias that forms the roots of tragic judgment and disastrous action by police officers is seldom the product of hatred. Instead, the ruinous biases often reflect profound indifference to the well-being of selected others or contempt for the value of specific others.

Objective testing that detects how candidates approach other people when they believe they are not being closely supervised can contribute to bias detection. Interview questions that require the candidate to reflect on individuals’ intrinsic worth can also help. For example, “Why do you think some people get themselves into legal problems over and over again?” is one way to look for a simplistic, ideological, and problematic approach to community members. Better candidates appreciate the complex influences on some people’s lives, including lack of resources and opportunities beginning in childhood, the barriers faced by many people in minority groups, addiction, the cascades of misfortune that accumulate, and other factors. Less-qualified candidates will often provide brief and “off the cuff” remarks about “poor choices.” Many of those undesirable interview responses seem dismissive or potentially contemptuous. The less specific and detailed answers should be given lower scores, and answers reflecting intolerance and poor judgment should be carefully noted.

True psychopathology in leadership candidates is rare. Any assessment process that is limited to investigation of mental illness is not likely to uncover destructive bias.

Creating an Intelligence-Led Promotional Algorithm

Police departments can create their own algorithms to improve promotion decisions. A closed feedback loop about promoted candidates’ job performance will inform the next promotional process. The first step in that loop is to emphasize to successful candidates that their performance will be judged in large part by the performance of their team. After three to six months on the job, the team’s performance against goals and engagement with the leader needs to be assessed, preferably through focused conversations with individual team members. Then there needs to be a review of the selection process to see which aspects of that process predicted the outcome. With time and promotions, key interview questions will emerge, and many interview items will be discarded and replaced. Most departments will find that the least useful interview questions are “pets” that seem astute and entertaining but are often simply off-putting to good candidates. Other mistakes with the interview include the examiners failing to score answers to each question.

Selection teams should identify objective tests whose ability to separate more effective and less effective law enforcement managers has already been demonstrated. Chosen tests should address both everyday work habits and potentially negative qualities that emerge only under pressure or when the individual feels comfortable to use complete discretion.

Building an algorithm around objective test scores can also be done at the agency. First, current managers who have a well-earned reputation for engaging with and for enhancing the performance of team members should be selected as validation targets. Their test scores should be examined for commonalities, and then compared with test scores of supervisors whose teams performed poorly and often sought transfers. Testing used in the current research created 440 individual score combinations. Those score combinations were given weights and then examined by comparing scores of eight clearly “more effective” and “less effective” samples of law enforcement and private industry managers. The algorithms were applied to the groups and individuals previously mentioned.

In addition to reducing subjective bias in promotions, the scored interviews and testing algorithm help analyze the closed feedback loop, allowing the department to continually improve the promotion process.

Notes:

1Jonathan Houdmont, “Stressors in Police Work and Their Consequences,” in Stress in Policing: Sources, Consequences and Interventions, ed. Ronald J. Burke ( New York, NY: Routledge. 2006), 50–65.

2Joyce Hogan, Robert Hogan, and Robert B. Kaiser, “Management Derailment: Personality Assessment and Mitigation,” in American Psychological Association Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology, vol. 3, ed. Sheldon Zedeck (Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 2011), 555–575.

3James K. Harter, Frank L. Schmidt, and Theodore L. Hayes, “Business-Unit-Level Relationship between Employee Satisfaction, Employee Engagement, and Business Outcomes: A Meta-analysis,” Journal of Applied Psychology 87, no. 2 (2002): 268–279.

4Aaron Chalfin et al., “Productivity and Selection of Human Capital with Machine Learning,” American Economic Review 106, no. 5 (124–127); Richard P. Larrick and Daniel C. Feiler, “Expertise in Decision Making,” in The Wiley Blackwell Handbook of Judgment and Decision Making, eds. Gideon Keren and George Wu (Malden, MA: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., 2015): 696–721.

5Robert B. Kaiser, Robert Hogan, and S. Bart Craig, “Leadership and the Fate of Organizations,” American Psychologist 63, no. 2 (February–March 2008): 96–110; Fred Luthans, “Successful vs. Effective Real Managers,” The Academy of Management Executive 2, no. 2 (May 1988): 127–132.

6Jaana Kuoppala et al., “Leadership, Job Well-Being, and Health Effects—A Systematic Review and a Meta-Analysis,” Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 50, no. 8 (August 2008): 904–915.

7See William M. Grove et al., “Clinical Versus Mechanical Prediction: A Meta-Analysis,” Psychological Assessment 12, no. 1 (March 2000): 19–30.

8Scott Gregory, “The Most Common Type of Incompetent Leader,” Harvard Business Review, March 30, 2018.

Please cite as

James M. Fico, Richard Myers, and Karen Ashley, “Intelligence-Led Leadership Selection,” Police Chief Online, December 16, 2020.