Successful implementation of a group violence intervention (GVI) strategy must involve collaboration and participation from the local police agency as a critical stakeholder that is responsible for leading several components of the strategy. However, interagency collaboration has been noted as one of the primary challenges in implementing GVI strategies.1 The current article seeks to provide a recent evaluation of the strategy in Memphis Tennessee, a U.S. city struggling with historically high rates of violent crime and experiencing increases in homicides and gun-related violence, and offers key recommendations to improve collaboration between the police and other GVI strategy stakeholders.2

There are several benefits of police participation in GVI programs. At the highest level, successful implementation will decrease agencies’ violent crime case numbers. Moreover, collaboration with other criminal justice agencies like the district attorney’s office and probation and parole contacts may also lead to valuable resource-sharing opportunities. For example, police may learn about any potential escalations of violence from probation or parole officers. They may also learn from community members about ongoing threats of violence in a neighborhood.

What Is Group Violence Intervention?

The GVI model was formulated by criminologist David Kennedy and based on the successful implementation of Operation Ceasefire in Boston, Massachussetts.3 It is a crime prevention strategy to reduce acts of gun violence by targeting group-involved individuals at risk of retaliatory violence. Prior research indicates that Operation Ceasefire, the initial version of a GVI strategy, was effective at reducing overall rates of violent crime in the targeted areas, including reductions in youth homicide, shots-fired calls for service, and recorded gun assault incidents.4 Given the consistent finding that group-involved individuals are a small piece of the overall population but make up over two-thirds of homicides and gun violence incidents in a district, the general goal is to deter group members from committing further acts of violence through (1) a focused deterrence component; (2) community moral message; and (3) supportive services.

Focused deterrence messaging takes place through call-in meetings or custom notifications. Call-in meetings are structured meetings where public safety figures (e.g., prosecutors, chiefs of police, mayors, and community members) deliver a deterrence message and a supportive services coordinator offers services (e.g., mental health resources and GED programs) to individuals on probation or parole. Custom notifications involve the same deterrence messaging. GVI leaders provide them to anyone who is group involved and at risk of retaliatory violence that will not attend a call-in meeting voluntarily. This includes individuals who were recently identified as victims or perpetrators of violent crime but have not been formally charged or adjudicated. The community moral message against violence is provided by participating community stakeholders like church leaders and violence interventionists at custom notifications and call-in meetings. Finally, supportive services like GED and job placement programs are offered at the close.

The Crucial Role of Interagency Collaboration

Arguably the main barrier to GVI implementation is collaboration among participating agencies. The same challenge was present during a process evaluation of the strategy in Memphis. This challenge is not surprising considering the strategy’s involvement of several moving parts and stakeholders— GVI strategies involve community partners, trained violence interventionists, police personnel, probation and parole personnel, and representatives from the district attorney’s office, among others.

Among the agency collaborators, police agencies may hold one of the most essential roles in this strategy. Unlike violence intervention programs based only on community efforts, police officers are the primary liaisons for this type of violence intervention and sources of information. Liaison officers are sworn officers who make the first contact with the group-involved individual, usually trying to contact them or a family member over the phone to ask if they are willing to meet for a custom notification. A custom notification is a contact with a group member identified as at risk of engaging in (leading or directing others) in violence to deliver a deterrence message. Police officers also participate in the more formal call-in meeting, which involves the delivery of the deterrence message and supportive services to a group of gang-involved individuals on probation or parole. Police leaders are also often asked to assist in the delivery of the deterrence message at the call-in meetings, indicating that they are aware of gang members’ activities and will “pull every lever” to prevent further violence.

In addition to their role as liaisons, police officers must engage in at least two forms of information sharing with the GVI strategy leaders to help deliver the deterrence message to gang-involved individuals. One of the most important forms of information sharing is the group audit.5 The audit is about mapping out gang-involved individuals’ locations in the community and their connections to other gang members. This form of information sharing involves specific agency units like the gang and violent crime units’ collaboration with GVI strategists. The strategists and officers should be able to consistently gauge the active gangs in the community and the impactful players through this mode of information sharing. Police personnel are also responsible for bringing forth potential targets for custom notifications. This occurs during weekly shooting reviews where police officers are invited to provide information on individuals (victims or perpetrators) from cases they are working on who are determined to be group involved and may benefit from a custom notification. These meetings are separate from the weekly shooting reviews with the violence interventionists who are not sworn personnel.

Weekly shooting reviews or case referral meetings occur separately for officers and publicly funded violence interventionists because of the potential for tension and conflict to arise between the two and to shield the violence interventionists from being viewed as double agents. While the two entities are both publicly funded and serve the same goal of preventing violence in the community, there is a potential for a rift between the two groups. This is a valid concern, as research involving interviews with police personnel found some officers indicating distaste for the interventionists’ presence.6

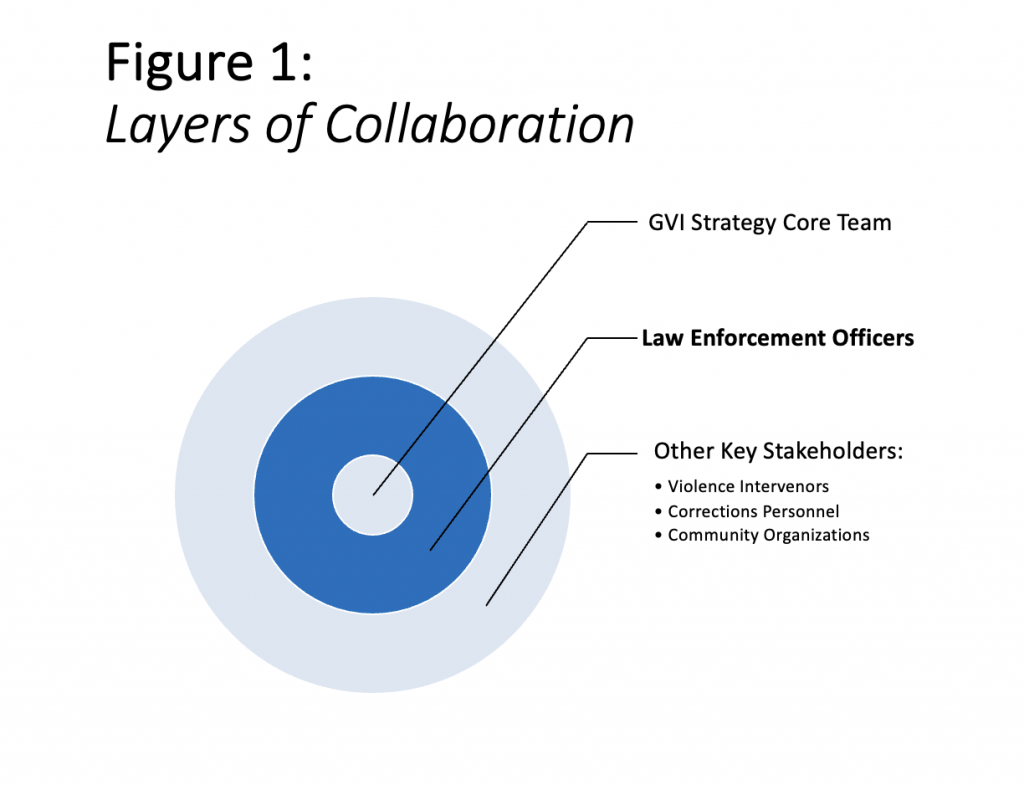

Figure 1 depicts the essential role and position of police in the GVI model employed in Memphis. The GVI strategy team is at the center of the effort. Strategy leaders must then rely on police personnel as resources of key information during the case referral and audit process. In addition, police officers serve as the main liaisons during custom notifications. The stakeholders indicated on the outermost layer have a slightly less pivotal responsibility but are still essential to the strategy. They must oversee crafting the deterrence message, mediating conflict, or delivering resources. These are all actions that take place after the work of liaison officers and police identification of individuals. Altogether, police involvement is pivotal to the strategy. The strategy involves sworn officers to serve as liaison officers, police leaders to assist in the delivery of deterrence messages at call-in meetings, and police information sharing to recommend targets for custom notifications and complete group audits. As a police agency navigates these responsibilities, they must collaborate with the other stakeholders to complete the delivery of the messages and resources.

Recommendations to Support Police Participation in a GVI Strategy

Memphis created its version of the GVI model to focus on combating gang-involved gun violence in the city. The Memphis Group Violence Intervention Program (GVIP) began operations in Fall 2022. From there, the program steadily built capacity. Results from a preliminary outcome evaluation indicate some success—there is a low-rearrest rate for recipients of custom notifications and call-in meeting participants.7 However, the process evaluation revealed challenges around interagency collaboration, which may have stymied further program success.

Without smooth collaboration, information ended up in silos—and frustration was evident among collaborators. The Memphis operations are a clear example of the necessity for consistent collaboration across criminal justice agencies and involved community partners for a successful strategy.

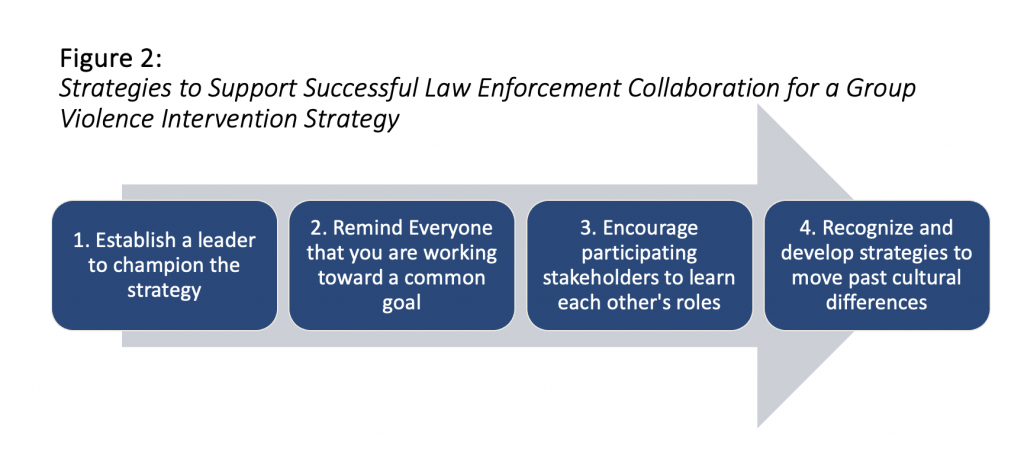

Memphis’ recent implementation of the GVI model offers several lessons for future implementations. Practical advice for increasing police collaboration and assistance with violence intervention implementation is described in more detail below. It includes (1) establishing a police leader to champion the strategy; (2) learning other stakeholders’ objectives and program goals; (3) recognizing differences in cultural perspectives; and (4) recognizing and developing strategies to move past cultural differences.

- Establish a Leader to Champion the Strategy

To remind them of their common goal, police agencies would benefit from a leader to champion the strategy specifically. As an example, a chief of police in Delaware recently signed on and has been outspoken about her jurisdiction’s implementation of the GVI strategy, suggesting that she turned to alternative methods of gun violence reduction because traditional police strategies were not working.8 That is, police leaders aware of the effectiveness of components of the GVI strategy and motivated to increase community trust in the police rather than engaging in further law enforcement activities would be ideal candidates to share the strategy and attempt to get their fellow officers on board. The importance of leadership when establishing collaborative partnerships is emphasized in early work on social work–police partnerships.9 It was further highlighted when examining the implementation of the Memphis GVI model. Several local officials were on board, but only a few police leaders advocated for the strategy. However, that has changed following the evaluation, which suggested police officers needed more support. The intervention strategy leaders felt that there was an initial lack of support. The city has nine patrol districts, but only three sworn liaison officers were assigned to the effort. This created the perception that the police didn’t fully support the strategy, which may have led to other city officials not fully supporting the strategy, which stymied the entire effort.

- Remember Everyone Is Working Toward a Common Goal

Agency collaboration can be incredibly challenging when competing goals and philosophies are at play.10 For example, probation or parole and the district attorney’s office each have a justice system focus, but the similarities end there. On a more discrete level, each agency has different responsibilities and tools or resources to do their work. Even within police agencies, different divisions and units have varying responsibilities and focuses. As a result, agencies and officers within agencies may not share information, a practice necessary for successful violence intervention. There needs to be officers, agency partners, and community members who can get information on what is happening in the community—and, for that information to not just end up in a silo, there must be a commitment to sharing that intel.

One way to establish a collaborative environment that involves a culture of information sharing needed for successful violence intervention among stakeholders and within a police agency may be reminding them of their shared goal of violence reduction. This can be done through intelligence meetings, which may create joint accountability and realize they are working toward the same goal.11 Another example that brought stakeholders together in Memphis was the governing board. The creation of the governing board in Memphis took place during the beginning of the evaluation period but created an open and collaborative conversation among the highest-ranking stakeholders (mayor, director of corrections, and chief of police) and key community stakeholders (council members and street violence interventionists). During these conversations, despite distinct roles in their agencies or community, each stakeholder should be able to connect with the goal of violence reduction. In terms of fostering collaboration within police agencies, intra-agency collaboration can also be emphasized in the same way. Though units and divisions in an agency may have varying responsibilities, they can be reminded of the shared objective to drive down violent crime rates.

- Encourage Participating Stakeholders to Learn Each Other’s Roles

A lack of desire to collaborate, especially in the form of information sharing, may stem from an absent understanding of other GVI partners’ workloads, responsibilities, and resources. As such, the development of a sense of each violence intervention stakeholder’s capacity should be shared. Providing information on each stakeholder’s responsibilities should extend to all participating agencies like probation and parole, violence interventionists, and even city officials. A clear idea of how each participating party will use information and connections to aid in the goal of violence prevention can alleviate any hesitancy and lack of trust.

For example, street intervention personnel may have a taut relationship with police officers. Trained interventionists typically have some criminal justice record and past gang involvement. While this makes them especially appropriate as interventionists, it also means a lack of trust between them and the police may be present. Some ways to alleviate mistrust and continue pursuing violence reduction may be education on each stakeholder’s roles and techniques in the strategy. In the same way, a clear and specific understanding of how police agencies use their skills and resources to aid in the strategy should also be well understood by street interventionists. This mutual understanding may lead to mutual respect for their roles.

A specific way to develop an understanding of everyone’s roles in the strategy is to provide and promote training opportunities. Though this is time-consuming, especially if a police agency is already stretched in its capacity, it may produce the necessary mutual respect across involved parties. Offering opportunities for community partners to engage in police GVI training and the inverse may help build an understanding of each other’s responsibilities. Within police agencies, training geared toward officers of all ranks and units may prompt even those less engaged in the strategy, like patrol officers, to take more actions like referring cases or individuals they suspect of being gang-involved for custom notifications. Allowing training opportunities for police of all ranks can also help build credibility and awareness of the program.

- Recognize and Develop Strategies to Move Past Cultural Differences

Police agencies’ focus on law enforcement directly clashes with social service organizations’ and street violence interventionists’ focus on mediation/conflict suppression and provision of therapeutic resources. Unfortunately, there is also no evidence-based model to provide guidance on a collaboration between social services and police in this particular type of project.12 Several cities have paved the path for districts looking to implement the strategy, but every locale differs. Collaborative efforts may be limited due to barriers like local politics and limited funding, which may differ by jurisdiction.13 Put differently, successful collaboration may depend on the cultural context of the locale in which it is being implemented. To this end, it appears that collaborative success for a violence intervention program rests on recognizing differences in stakeholders’ cultures and their ability to find common ground. With different goals, each stakeholder’s organizational values and attitudes around violence and the criminal justice system will undoubtedly differ. At the very least, developing an understanding of the differences in organizational contexts may assist in mutual respect and a willingness to collaborate. In Memphis, there was a clear cultural divide between the police and street violence interventionists.

City officials can aid in the understanding of variations in organizational cultures and build mutual respect by helping participating partners find common ground. Leaders can assist in establishing a collaborative culture within the group of GVI stakeholders, where, despite cultural differences, each partner acknowledges the importance of their role in violence reduction. City leaders can also take time to individually listen to each agency’s needs while implementing the strategy. This may be the key to easing stakeholder conflict stemming from cultural differences. That is, GVI partners may hesitate to collaborate because of competing interests, such as funding and support from city leaders. To this end, city leaders must carefully support each contributing partner, recognizing the importance of their roles and assuaging any idea that partners are competing for anything.

Conclusion

The recent GVI model in Memphis reiterates how important interagency collaboration is to successful implementation. The evaluation results indicated that the police are a key stakeholder, but like many other criminal justice organizations, they may struggle to recognize the importance of collaboration and information sharing. With the police as an essential partner in this strategy, there must be reflection on how barriers to collaboration with local police agencies may be lessened. The recent evaluation of the Memphis strategy included several recommendations for further implementation, such as establishing a police leader to champion the strategy, reminding all participants of their shared goal of violence reduction, encouraging training and learning about the roles of other stakeholders like street interventionists and corrections officers, and recognizing cultural barriers in order to work around them and move forward should conflict arise between partners. With these recommendations, cities interested in this type of intervention strategy can aim to successfully implement and move past those early barriers to full implementation. d

Notes:

1Camila Gripp, Chandini Jha, and Paige E. Vaughn, “Enhancing Community Safety Through Interagency Collaboration: Lessons from Connecticut’s Project Longevity,” The Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics 48, no. 4_suppl (2020): 47–54.

2Bill Hutchinson, “US Stats Show Violent Crime Dramatically Falling, So Why Is There a Rising Clash with Perception?” ABC News, March 22, 2024; Memphis Crime Commission, “Safe Community Plan Metrics.”

3David M. Kennedy, Anne Morrison Piehl, and Anthony A. Braga, “Youth Violence in Boston: Gun Markets, Serious Youth Offenders, and a Use-Reduction Strategy,” Law and Contemporary Problems 59, no. 1 (Winter 1996): 147–196.

4Athony A. Braga et al., “Problem-Oriented Policing, Deterrence, and Youth Violence: An Evaluation of Boston’s Operation Ceasefire,” in Gangs (Routledge, 2017), 513–543.

5National Network for Safe Communities, “Group Violence Intervention.”

6Maria Cramer and Hurubie Meko, “Arrests Expose Rift Between N.Y.P.D. and ‘Violence Interrupters,’” The New York Times, April 6, 2024.

7Rachael Rief and Bill Gibbons, An Evaluation of the Memphis Group Violence Intervention Program (Memphis, TN: Public Safety Institute, 2024).

8National Institute of Justice, “Police Use Science and Community Partnerships to Reduce Gun Violence,” June 26, 2023.

9George T. Patterson and Philip G. Swan, “Police Social Work and Social Service Collaboration Strategies One Hundred Years after Vollmer: A Systematic Review,” Policing: An International Journal 42, no. 5 (2019): 863–886.

10Lawrence J. Johnson et al., “Stakeholders’ Views Of Factors That Impact Successful Interagency Collaboration,” Exceptional Children 69, no. 2 (2003): 195–209.

11Gripp, Jha, and Vaughn, “Enhancing Community Safety Through Interagency Collaboration.”

12Patterson and Swan. “Police Social Work and Social Service Collaboration Strategies One Hundred Years after Vollmer.”

13Eddie Kane, “Collaboration in the Emergency Services,” in Fire and Rescue Services: Leadership and Management Perspectives, ed. Peter Murphy and Kirsten Greenhalgh (Cham, CH: Springer, 2018), 77–91.

Please cite as

Rachael Rief and Amaia Iratzoqui, “Interagency Collaboration in Violence Intervention Programs: Lessons Learned from the Implementation of a Group Violence Intervention Strategy in a Large Southern City,” Police Chief Online, July 17, 2024.