During this unprecedented time of COVID-19 and the call for law enforcement reforms, labor trafficking may be considered as a low priority for many agencies. Unfortunately, in this same environment of isolation, economic uncertainty, and heightened online activity, labor traffickers, enablers, and buyers thrive.

Human traffickers are becoming more tech savvy while the use of technology by stakeholders responsible for combatting labor trafficking is lagging. Calling labor trafficking “a crime hidden in plain sight,” the 2020 U.S. State Department’s latest Trafficking in Persons (TIP) Report identified the need to increase labor trafficking investigations and prosecutions as a top priority.1 Human trafficking, especially labor trafficking, has long been considered a low risk–high reward criminal activity. Until labor traffickers are convicted of a serious crime, human trafficking will continue to grow within and across the United States.

Labor trafficking cases and prosecutions are minimal in the United States. In 2019, only seven states attempted to prosecute a labor trafficking charge—and all seven combined labor with sex trafficking charges.2 None of these prosecutions resulted in a labor trafficking conviction within a criminal court. The pervasive explanation for the lack of investigations and prosecutions is the complexity of the crime, made all the more complicated by the lack of persons identifying themselves as victims of labor trafficking or the absence of victim testimony.

The dialogues and debates on reforms to improve investigations and prosecutions are extensive. Across the United States, local, state, and federal government, law enforcement, health and human service professionals, and service providers focus on improving individual and collective responses to prevent and protect victims and prosecute traffickers and their enablers. For example, several U.S Department of Justice-funded anti-human trafficking task forces have subcommittees dedicated to sharing, developing, and improving upon a diverse set of labor trafficking prevention initiatives, laws, and practices. For example, the Los Angeles Regional Human Trafficking Task Force’s labor trafficking subcommittee has members from across all sectors, jurisdictions, and agencies. They examine and review a wide range of issues including specialized investigation and awareness trainings, streamlining state and federal labor trafficking laws, victim restitution, information-sharing technologies, victim-centered investigations, and evidence-based prosecutions.

It is not only large cities that recognize the need to improve labor trafficking response. The New Hampshire Regional Human Trafficking Task Force has collaborated with the Los Angeles subcommittee on how to best tailor issues and outcomes based on labor trafficking activities specific to their region.

Stakeholders understand that sharing lessons learned and establishing best practices requires multiagency information sharing if the dismal arrest and criminal conviction rates are to be improved. Most fundamental and critical to execution is the quick, easy use of affordable and reliable technology that efficiently gathers, processes, and visualizes human trafficking triggers across several data sources. Traditionally, only businesses could afford sophisticated technologies to aid highly specialized efforts. For example, detection of labor trafficking throughout supply chains, which, when identified, is largely handled quietly and remains within the corporation. Today, these powerful technologies can be developed, maintained, and scaled economically and within the budgets of law enforcement agencies. However, before law enforcement can fully achieve sustainable value through these or any network effect technologies, one condition must be met—multidisciplinary, cross-sector data sharing.

Shifting to a data sharing mindset is difficult but not insurmountable. It is worthwhile to examine and reflect upon the game-changing outcomes of new, inexpensive, and powerful technologies that can be operationalized if the mindset barrier is overcome. The concepts and technology platforms briefly presented herein can specialize around any crimes, particularly complex crimes or crimes prosecuted without victim testimony (domestic violence).

A Perfect Storm

Even with the best of intentions and knowledge, from all sides at all levels, increasing investigations and prosecutions is a lot to ask from an under-resourced law enforcement system. It requires bold and steadfast political will toward a crime requiring long-term investigations, resources, and case law. It demands specialized detectives during a time of low attraction and attrition rates and needs pressure from the top to shift detectives away from the CompStat and vice models toward victim-centered or evidence-based policing and prosecution. Even if these barriers are overcome, gathering labor trafficking intelligence also requires significant time from investigators to sift and sort volumes of data. Add to this low budgets, frequent agent transfers, and the lack of self-identifying victims or victim testimony, and the perfect storm exists for labor traffickers acting with impunity .

Despite the constraints of pursuing a labor trafficking case and securing conviction, government, law enforcement, and civil society all want labor traffickers and buyers convicted of a major crime. While public attention is largely focused on sex trafficking, it is equally important to recognize the demoralizing effects on law enforcement agents dedicated to identifying labor trafficking victims and investigating the traffickers. Preventing officers from investigating a major crime in favor of a resource-, CompStat-, and vice-friendly charge, or worse still, a labor and wage penalty, can take its toll. Low morale is the most costly of all resources and can lead to high attrition, rates, low retention rates, and higher requests for transfers.

Levering Technology: Silos Work

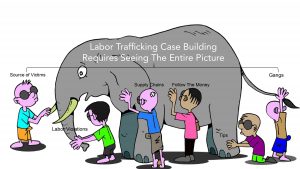

When building a case, the goal of labor trafficking detectives is to make connections between individual pieces of intelligence that in turn create actionable insights that can lead to a labor trafficking charge. Due to its complexity, the crime must be seen in its entirety. For example, it demands recognition that a single criminal event may have multiple offenders: the individual (owner of the business), institutions (recruitment companies), and trafficking networks (domestic or transnational).

In order to view labor trafficking in its entirety, gaining insights into the core elements is essential. Multiple agencies across sectors each have intelligence that, when combined, make up these core elements. From a tech perspective, the individual intelligence refers to the isolated data streams (silos) that hold the data points relevant to labor trafficking. By retrieving and connecting these data points, technology can aid the investigator and prosecutor with actionable insights far more quickly and precisely than any amount of human effort can ever hope to achieve.

“We understand that the only response to any form of human trafficking, particularly labor trafficking, is through information sharing and collective action. Committed to providing the citizens of the United States with the best possible operational response, the Department of Justice supports multi-sector human trafficking task forces. Active across the nation, and growing in scale and impact, our collaborative model task forces continue to increase human trafficking awareness, human-led and data driven intelligence and improvements in human trafficking prevention, protection and preparedness.” —Bill Woolf, Principal Deputy Director, Office for Victims of Crime

The popular solution to provide quick intelligence from multiple data sources calls for structural change in the form of tearing down silos in favor of an enterprise system. This system, with permission from the holders of siloed data, organizes, combines, and manages datasets into one large database. The intended purpose of these systems is to provide agents with a one-stop data gathering shop. The enterprise system differs across organizations but in general it hosts intra-agency, cross-departmental data. For very large agencies, such as the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, the sheer volume of intra-agency intelligence and number of diverse departments gives this system real value. However, even this type of system needs outside data sources to build a labor trafficking case. For state and local law enforcement agencies, the scope and breadth of data does not provide enough meaningful information for the labor trafficking detective. Additionally, one vast multiagency, cross-sector platform is unrealistic and unnecessary.

While the enterprise system has its merits, leaders and end-users question the return on investment measured in time saved and cases built. For many agencies, an enterprise system is simply too expensive to develop, install, and maintain. Questions arise around the larger systems’ ability to solve several major issues: access to relevant data outside of the system; time spent retrieving data; and affordability to install, maintain, and scale. Most importantly, tearing down silos destroys data systems that were organized for a reason and serve a focused use. Tearing silos down hinders the ability for data to achieve their original, worthwhile purpose. In sum, these large systems too often miss the mark for value creation for law enforcement.

The problem to be solved is the need to retrieve data that meets the agent’s objective, quickly and easily. Today’s innovative technologies can retrieve specific data points from internal and external data sources. By retrieving and combining data points from a multitude of systems, modern technologies can be programmed to identify labor trafficking triggers within and across data sets regardless of where the data sit. Thus, these technologies (and cloud storage) can eliminate the costs and limitations presented by enterprise systems by providing access to aggregated data from where they sit, unencumbered by the data’s original purpose. These affordable and easy-to-use technologies can save time by pulling, connecting, and providing insights based on the data needed to meet the objectives of the labor trafficking investigator. Artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning can begin, which, once achieved, will decrease the crime of labor trafficking due to the offenders’ very real fear of getting caught and forfeiting profits. Systems that achieve AI and machine learning for a specified crime will eventually reduce the need for specialized knowledge to make labor trafficking queries. This allows agents to spend less time on understanding intelligence and more time on case building. It also compensates for the constant movement of investigators across departments by building on the knowledge and experience of their predecessors.

Human Trafficking Search Engines

A promising development is the use of specialized search engines that can access data relevant to the crime. By securing permission of silo holders to search aggregated databases, investigators can make specific inquiries at an increasingly affordable rate, initiate the AI and machine learning process, and establish uniformity across indicators (necessary for the AI and machine learning process). Until machine learning is achieved, specialized knowledge of indicators to query is required (but less so than with a non-machine learning system), inferences and visualizations will be limited, and the engine’s full power will only be as strong as the data it can access. However, despite these limitations, it offers greater economic value in the short term than most options, and enormous value when AI and machine learning is executed. Simply put, think Google search engine for human trafficking.

Mapping as Information Sharing

Another technology solution helpful for human trafficking investigations is mapping of pre-determined indicators through layering. This can provide strong visualizations and patterns of labor trafficking red flags. Not only does this have the potential to alert the investigator with real-time actionable insights but it reduces the need for specialized knowledge of labor trafficking indicators and the time needed to locate and make sense of the most relevant information.

Conclusion

When planning a technology strategy, it is essential to keep in mind that the agent is the solution. Technology assists in reaching one objective—helping law enforcement make decisions. Today, law enforcement agencies of all sizes and budgets can leverage affordable technology to proactively (1) detect labor trafficking triggers with a high degree of specificity and accuracy; (2) pull triggers from large data sets across multiple sources and purposes; and (3) integrate the unique data into the agency system (or devices). Time and money do not need to be spent on breaking down silos or developing large enterprise systems to efficiently operationalize information. The technology is there, all it needs are humans with data-sharing mindsets.

Notes:

1 U.S. Department of State, Trafficking in Persons Report, 20th ed. (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of State, 2020).

2Kyleigh Feehs and Alyssa Currier, 2019 Federal Human Trafficking Report (Human Trafficking Institute, 2020).

Please cite as

Alan Wilkett and Kimberly Adams, “Investigative Firepower to Combat Labor Trafficking: Leveraging Powerful and Affordable Technology to Improve Response,” Police Chief Online, November 11, 2020.