Human trafficking, including both sex and labor trafficking, is a heinous crime that removes all humanity from victims and denies them basic human rights. According to the 2021 Trafficking in Persons Report created by the U.S. State Department, human trafficking has become the second largest criminal activity across the globe, rapidly approaching drug trafficking.1 Furthermore, according to Polaris, human trafficking is a global industry worth $150 billion dollars annually.2 The International Labor Office indicates that roughly 25 million people globally are subjected to forced labor.3 Recent research conducted by the University of Pennsylvania discovered that at least half-million people in the United States are currently living in the conditions of forced labor.4 However, when people often envision human trafficking, typically their first thought is normally sex trafficking. Labor trafficking is frequently ignored, and most people would not recognize the signs of labor trafficking. For decades, both law enforcement agencies and academia have focused heavily on sex trafficking, gathering data and conducting research to assist in its prevention, with little attention directed at labor exploitation. Labor trafficking does exist in the United States; it is a form of modern-day slavery where individuals perform labor or services by means of force, fraud, or coercion. According to the U.S. Department of Homeland Security’s Homeland Security Operational Analysis Center, trafficking and smuggling at the U.S. southwest border generates an estimated $6 billion annually.5

Labor cases are complex to investigate, and many agencies are not trained in state and in federal labor laws. The Human Trafficking Institute’s 2022 Federal Human Trafficking Report shows U.S. federal prosecutors concentrated 94 percent of trafficking prosecutions on sex trafficking and6 percent on forced labor cases.6 Conversely, experts have estimate that 70 percent of persons trafficked are in fact for forced labor. 7

Measuring the extent of human trafficking is often difficult, mainly because of its clandestine nature, thus making it more difficult to identify. To complicate the matter further, there are other barriers to early identification including language, citizenship status, distrust, and work-specific practices. According to the National Human Trafficking Hotline, there have been 5,000 calls about labor trafficking in the United States, primarily identifying instances in domestic servitude, agriculture, traveling sales, restaurant/fast food, and the health and beauty service industries.8

Human trafficking encompasses transnational trafficking, which involves transit between two or more countries, and domestic or internal trafficking, which occurs within a single country. Examining both U.S. citizens and non-citizens is an important aspect for law enforcement, particularly when understanding factors that “pull” and/or “push” someone into the forced labor funnel. “Push” (supply) factors are circumstances which tend to “push” the victims out of their current location while “pull” (demand) factors tend to attract the victims to those seeking to prey on such individuals. These factors occur because people are pushed out of their current environment for many reasons, including displacement due to conflict, violence, poverty, unstable housing, and unfulfillment of basic needs (food, safety, etc.). They are pulled into different locations that have better economic conditions with corresponding demands for labor. “Push factors” that provoke travel are often poverty, the lack of social or economic opportunity, and human rights infringements. Conflicts can create major displacements of people, leaving women and children vulnerable to trafficking. When the origin country is devastated by war and destination countries are free of similar conflict, potential victims will be pulled toward stability. Those who desire to improve their quality of life by leaving their home countries can be deceived by trafficking offenders who coerce and manipulate them.9

Barriers to Reporting

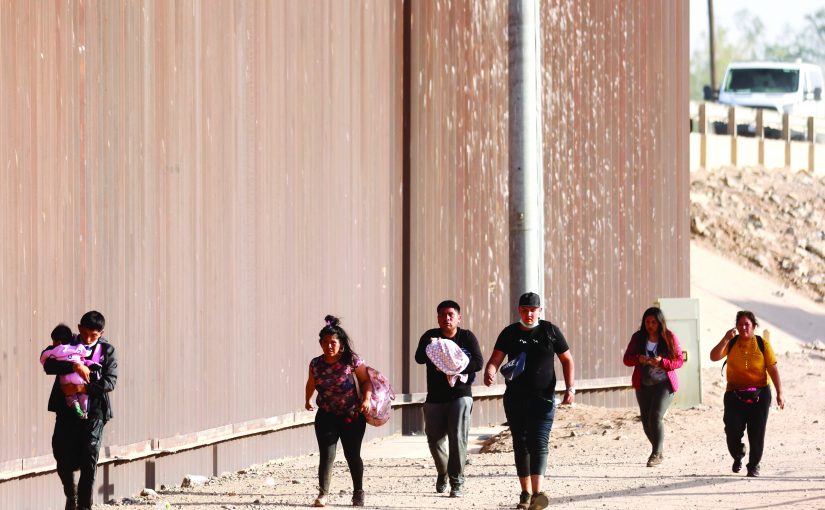

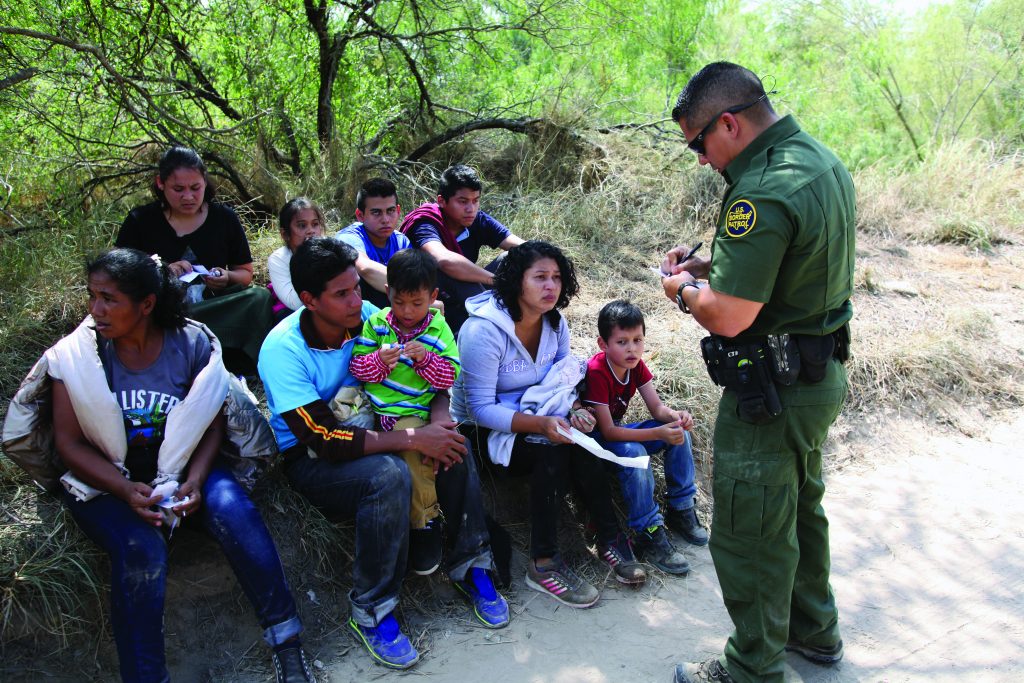

According to U.S. Customs and Border Protection data, the number of undocumented immigrant crossings at the U.S. southwest border surpassed 2.76 million people in 2022, shattering the previous record by more than 1 million.10 Economic stressors on families in their own countries have put them at a larger risk for exploitation by smugglers and traffickers as they seek to migrate across the U.S. border. Polaris estimates that the U.S. industry most likely to victimize illegal immigrants is the agriculture industry and that six out of ten victims are from the Latin American community.11 Exacerbating the problem is the recent pandemic, which has accelerated labor exploitation. Exact figures are difficult to ascertain because the crime is underreported, and research associated with the effects is lacking.

According to U.S. Customs and Border Protection data, the number of undocumented immigrant crossings at the U.S. southwest border surpassed 2.76 million people in 2022, shattering the previous record by more than 1 million.10 Economic stressors on families in their own countries have put them at a larger risk for exploitation by smugglers and traffickers as they seek to migrate across the U.S. border. Polaris estimates that the U.S. industry most likely to victimize illegal immigrants is the agriculture industry and that six out of ten victims are from the Latin American community.11 Exacerbating the problem is the recent pandemic, which has accelerated labor exploitation. Exact figures are difficult to ascertain because the crime is underreported, and research associated with the effects is lacking.

A major factor that makes uncovering and recording labor trafficking difficult is the victim’s hesitancy to come forward about labor exploitation. Victims who are smuggled into the United States or who were brought into the United States. on a visa that has since expired, fear detection and deportation and therefore are less likely to report their exploitation.12 Being undocumented increases a victim’s vulnerability for exploitation by a trafficker.13 The United States has been the leading destination for migrants for the last half century; therefore, migrants often become victims of labor trafficking because they are already fleeing poverty in their own countries and seeking economic opportunity, according to the 2022 World Migration Report.14

Law enforcement identify few U.S. victims of labor trafficking because they are more likely to think of U.S. citizens as victims of sex trafficking.15 U.S. citizens have a multitude of “push” factors (the idea of a better life) that increase the risk of labor trafficking victimization, including socio-economic backgrounds, cognitive disabilities, low levels of education, foreign substance addictions, and homelessness.16 Traffickers exploit these factors, and the “pull factor” is the need for slave labor (even within the borders of the United States.). This is obtained by exploiting those in vulnerable positions. U.S. citizens face exploitative practices that fall under a range of labor law violations, such as wage and tip theft, hazardous working conditions, pay deductions, and legal exemptions such as agricultural industries, which are exempt from paying overtime and require workers to work long hours.17

Runaway and homeless youth are commonly forced by employers to participate in door-to-door sales, begging networks, and peddling in dangerous areas over long workdays.18 Victims receive little pay, limited food, and unhealthy living conditions in return for promises of stable housing and income.19 The promise of a better life pulls them into the exploitation of labor, which can be coupled with pushing the victim into criminal activity. This criminal activity typically impedes the reporting of labor trafficking by victims. A multi-city study found that 81 percent of homeless youth who were victims of labor trafficking were also forced into drug dealing through coercion and violence.20 Employers maintain power over youth workers through physical and psychological violence, yet authorities often do not label these cases as trafficking. This makes it difficult to identify cases because what is the youths are performing illegal acts and have been told by their traffickers that they can be arrested, thus discouraging reporting.

Vulnerabilities of Immigrant Populations

Understanding the root cause as well as push and pull factors that funnel people into labor trafficking can lead to a better understanding of the vulnerabilities that immigrant populations in the U.S. face. The Polaris Project research noted that the National Human Trafficking Hotline identified between 2015-2018, 50% of persons trafficked for labor are from Latin America.21 For instance, exploring a case involving “Marco” was conducted by Investigators with Hope for Justice, a global nongovernmental organization (NGO) combatting human trafficking (see sidebar).

The case shared in the sidebar illuminates the vulnerabilities and barriers faced by immigrants, many of whom are exploited for labor in the United States. Labor trafficking vulnerabilities encompass a wide range of situations that are often traumatic. As previously stated , these factors include poverty, homelessness, lack of education or educational opportunities, migration, and a lack of citizenship status, among other risk factors.23 One of the most critical factors is poverty and a lack of economic opportunity in the person’s home country or even within the United States. Most of the migrant farmworkers who come to the United States are fleeing some form of violence and nearly all of them have identified poor economic conditions as a strong factor affecting their plans to migrate to the United States.24 The desire to feed and house an entire family unit often results in whole households leaving and migrating to the United States, where they believe there to be more economic opportunities. This is often where the vicious cycle of debt bondage begins. Migrants often hire smugglers to get them into the United States, where they will work to pay off the debt. The smugglers will often increase fees and charges, so it is difficult for the person to ever fully resolve the debt. This cycle leaves the individual as an indentured servant.

An often-underreported vulnerability seen in victims is that they do not feel victimized. One potential explanation for this misperception is that victims often have a specific definition of what a victim of crime is that does not include their experience. A second barrier to victim recognition is that victims often consent to work under circumstances that legally constitute the crime of human trafficking.25 Migrants consciously leave their home country in search of work and the promise of a better life, and many view the inhumane working conditions as just a temporary situation to endure so as to better themselves and their family.26 As a result, victims may feel as though they are in control of their own lives and can make decisions about who and how they work to include the working conditions.27

When a country, state, or even a neighborhood is in a time of violent conflict, there is often a reduction or absence of law enforcement and access to basic services including food and shelter. This leaves people desperate to provide for themselves and their families. According to the Global Report on Trafficking, militant groups take advantage of the lawless conditions and people’s desperation, forcing people into sexual slavery, forced labor, and even trafficked for use as armed combatants.28

Another all too often-ignored vulnerability is the perception by law enforcement, in that law enforcement often does not fully recognize the scope of the human trafficking problem in the communities they serve. The belief that the problem is not occurring in their jurisdiction allows agencies to place other enforcement and budgetary priorities above human trafficking concerns.29 Public and law enforcement perception of labor trafficking is placed on a lower level of priority than sex trafficking. Sex trafficking is easier to identify by law enforcement and by the public, and law enforcement tends to rely on public reports/tips, which are more common for sex trafficking cases than labor trafficking cases. This emphasis on investigating and combating sex trafficking over labor trafficking is a real and challenging issue for modern law enforcement and heightens the vulnerability of those exposed to labor exploitation.

The Need for Training

Law enforcement perceptions are coupled with a lack of quality training available to law enforcement, in particular training at the patrol level. Training frontline officers is of the utmost importance as patrol officers are likely to have more contact with the public than detectives would, thus the officers are in a unique opportunity to identify more victims. One study demonstrated that over 80 percent of the victims identified by a federally funded human trafficking taskforce were victims of sex trafficking. The victim services provider for that same taskforce showed much different numbers, identifying that 64 percent were actually labor trafficking victims and only 22 percent were identified as victims of sex trafficking. This concluded that labor trafficking was a significant issue that went unidentified by law enforcement.30 This, along with additional supporting research, further illustrates the need for continued training as well as highlighting the benefits of victim service providers and law enforcement to working collaboratively.

Law enforcement training needs to encompass a general understanding of what sex and labor trafficking are on a state, national, and international level. Once knowledge of these crimes is established, the training needs to be tailored and focused on the geographic area the officers work in every day, as the issues in one jurisdiction may look quite different from those in another jurisdiction. The training should focus on screening for and spotting the signs of sex and labor trafficking, focusing on ways officers can identify victims and then concentrating on what steps to take after a victim has been identified. Additionally, it is imperative that trauma-informed care and victim-centered investigation tactics be incorporated. This training is often taught by victim advocates and health care partners. Incorporating these topics in law enforcement training is also a great opportunity for officers to meet and collaborate with other victims, groups, and stakeholders.

To move forward in combating human trafficking, law enforcement must recognize and utilize all services available to assist in this mission . Over the last 20 years, the U.S. government has taken steps to combat human trafficking by establishing the Trafficking Victims Protection Act (TVPA), which defines human trafficking.31 The U.S. government has updated and added language to bolster the TVPA, leading to the Enhanced Collaborative Model (ECM) Task Force to Combat Human Trafficking Programs. According to a study, Evaluation of the Enhanced Collaborative Model to Combat Human Trafficking Technical Report, law enforcement must improve in several areas to effectively address human trafficking:

-

- Gain access to additional resources, infrastructure, and training that focus specifically on labor trafficking.

- Develop and nurture strong partnerships with regulatory agencies such as the U.S. Department of Labor.

- Work at identifying areas at risk of labor trafficking.

- Develop skills and expertise for law enforcement to identify and gather intelligence about potential labor trafficking victimization.

- Increase knowledge of what visas are available for those victims who may be undocumented.32

Having law enforcement well versed in not only the identification of potential victims but understanding how to proceed after the identification is made will, it is hoped, be a step toward decreasing the number of trafficked people in the United States.

“Proactive work in communities will support these efforts and improve strong relationships with those that are susceptible to trafficking.”

Multi-disciplinary teams (MDTs) should include law enforcement, prosecutors, medical staff, mental health staff, forensic interviewers, victim services specialists, advocates, housing personnel, treatment facilities and personnel, NGOs, and travel and transportation personnel, all with an understanding of the victim-centered approach. An MDT can be conceptualized as a puzzle—if one piece is missing, the picture is not complete. If pieces are missing from MDTs, they will fail to serve victims and survivors. Proactive work in communities will support these efforts and improve strong relationships with those that are susceptible to trafficking.

Serious consideration must be given to dedicating more funding in this area (victim services and law enforcement), as well as to training law enforcement in trafficking indicators and follow-up actions once a victim has been recovered. Given that victims seldom self-identify, investigations must be approached from a victim-centric lens. This leads to assisting victims through recovery, yielding useful information that law enforcement can use later. Utilizing an NGO in the community to assist with housing, victim necessities, treatment, advocacy, counseling, transportation, translation, investigations, and intelligence helps reduce the overall cost associated with combating human trafficking per agency.

Very few officers are engaged in investigations regarding labor trafficking, and only a very small fraction of law enforcement is trained in human trafficking. Most of the training focuses on sex trafficking and prostitution, overlooking labor trafficking entirely.33 A study entitled Policing Labor Trafficking in the U.S. identified several factors that have led to the lack of law enforcement responses to labor trafficking—the lack of clarity around the definition of the crime, the lack of agency readiness, and the routines of police work that guide officers away from labor trafficking cases.34

The connection to the identified factors can be linked with a later study, entitled Evaluation of the Enhanced Collaborative Model to Combat Human Trafficking, Technical Report. This study identified challenges such as the lack of knowledge among law enforcement and prosecutors about labor trafficking. In fact, 9 of the 10 prosecutors on Enhanced Collaborative Model task forces reported they had little to no experience prosecuting cases of labor trafficking.35 Additionally, the complexity of the investigation process and lack of resources to fully support the investigation of labor trafficking means more law enforcement departments (whether local, state, and federal) need dedicated enforcement officers/agents and additional personal for the “long haul.” Finally, the lack of survivor identification and cooperation due to fears of deportation or penalty of incarceration goes hand in hand with trust within the law enforcement community, an important area of focus for the profession as a whole. 🛡

Notes:

1U.S. Department of State (DOS), Trafficking in Persons Report (Washington, DC: DOS, 2021).

2Polaris Project, ”Partnerships.”

3Michelle De Cock, Directions for National and International Data Collection on Forced Labour, Working Paper No. 30 (Geneva: International Labour Office, 2007).

4Xin Shiyan, “Digging into US Crimes of Human Trafficking and Forced Labor,” Global Times, August 18, 2021.

5Financial Crimes Enforcement Network, “FinCEN Issues Alert on Human Smuggling Along the Southwest Border of the United States,” news release, January 13, 2023.

6Human Trafficking Institute, Prosecution of Human Trafficking Cases (2022).

7Monique Villa, Slaves Among Us: The Hidden World of Human Trafficking (Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2019).

8Polaris Project, Data Report: The U.S. National Human Trafficking Hotline (2019).

9Andrew Yang, “Factors that Lead to Human Trafficking,” The Borgen Project Blog, September 14, 2019.

10Julia Ainsley, “Migrant Border Crossings in Fiscal Year 2022 Topped 2.76 Million, Breaking Previous Record,” NBC News, October 22, 2022.

11Polaris, “Latin America.”

12Ufuoma Agarin et al., Freedom Is Free, Labor Isn’t: Bringing Awareness to Labor Trafficking in Maryland (Maryland: Shriver Center, University of Maryland, 2014); Kelle Barrick et al., “When Farmworkers and Advocates See Trafficking, But Law Enforcement Does Not: Challenges in Identifying Labor Trafficking In North Carolina,” Crime, Law and Social Change 61 (2014): 205–214; Denise Brennen, Life Interrupted: Trafficking into Forced Labor in the United States (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2014); Shelley, Cavalieri, “The Eyes that Blind Us: The Overlooked Phenomenon of Trafficking into the Agricultural Sector,” Northern Illinois University of Law Review 31 (2011): 501–519; Colleen Owens et al., Understanding the Organization, Operation, and Victimization Process of Labor Trafficking in the United States (Urban Institute, 2014).

13Sheldon X. Zhang et al. “Estimating Labor Trafficking among Unauthorized Migrant Workers in San Diego,” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 653 (May 2014): 65–86.

14IOM: UN Migration: World Migration Report 2022 (United Nations, 2021).

15 Amy Farrell, Rebecca Pfeffer, and Katherine Bright, “Police Perceptions of Human Trafficking,” Journal of Crime and Justice 38, no. 3 (2015): 315–333.

16Kevin Bales, Disposable People: New Slavery in the Global Economy, 2nd Ed. (University of California Press, 2004); Barrick et al., “When Farmworkers and Advocates See Trafficking, But Law Enforcement Does Not”; Hila Shamir, “A Labor Paradigm for Human Trafficking,” UCLA Law Review 60 (2012): 76–136; Sheldon X. Zhang, Smuggling and Trafficking in Human Beings: All Roads Lead to America (Praeger Publishers, 2007); Sheldon X. Zhang, Looking for a Hidden Population: Trafficking of Migrant Laborers in San Diego County (San Diego, CA; San Diego State University, 2012).

17Thomas A. Arcury et al., “Job Characteristics and Work Safety Climate among North Carolina Farmworkers with H-2A Visas,” Journal of Agromedicine 20, no. 1 (2015): 64–76; Human Rights Watch, “US: Child Workers in Danger on Tobacco Farms,” news release, May 14, 2014.

18Katherine Kaufka Walts, “Child Labor Trafficking in the United States: A Hidden Crime,” Social Inclusion 5, no. 2 (2017).

19Laura T. Murphy, Labor and Sex Trafficking Among Homeless Youth: A Ten-City Study—Full Report (New Orleans, LA: Modern Slavery Research Project, Loyola University New Orleans, 2017); Dominique Roe-Sepowitz, Kristen Bracy, and Kimberly Hogan, Youth Experiences Survey 2018: Year Five (Arizona State University, 2018); Dominique Roe-Sepowitz, Kristen Bracy, and Kimberly Hogan, 2020 Youth Experiences Survey (Arizona State University, 2021); Walts, “Child Labor Trafficking in the United States: A Hidden Crime.”

20Murphy, Labor and Sex Trafficking Among Homeless Youth.”

21Polaris Project, Data Report: The U.S. National Human Trafficking Hotline.

22William Adams et al., Evaluation of the Enhanced Collaborative Model to Combat Human Trafficking, Technical Report (Urban Institute, 2021).

23Corinne Schwarz et al., “The Trafficking Continuum: Service Providers’ Perspectives on Vulnerability, Exploitation, and Trafficking,” Affilia: Feminist Inquiry in Social Works 34, no. 1 (2019): 116–-132.

24Jeremy S. Norwood, “Labor Exploitation of Migrant Farmworkers: Risks for Human Trafficking,” Journal of Human Trafficking 6, no. 2 (2020): 209–220.

25Masja van Meeteren and Jing Hiah, “Self-Identification of Victimization of Labor Trafficking,” in The Palgrave International Handbook of Human Suffering, eds. John Wintrerdyk and Jackie Jones (Palgrave Macmillan, 2020).

26Meeteren and Hiah, “Self-Identification of Victimization of Labor Trafficking.”

27Meeteren and Hiah, “Self-Identification of Victimization of Labor Trafficking.”

28UN Office on Drugs and Crime, Global Report on Trafficking in Persons 2018 (New York NY: United Nations, 2018).

29Farrell, Pfeffer, and Bright, “Police Perceptions of Human Trafficking.”

30Amy Farrell and Rebecca Pfeffer, “Policing Human Trafficking: Cultural Blinders and Organizatioal Barriers,” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 653, no. 1 (May 2014): 46–64.

31U.S. Department of Justice, “Human Trafficking: Key Legislation.”

32Adams et al., Evaluation of the Enhanced Collaborative Model to Combat Human Trafficking, Technical Report.

33Farrell and Pfeffer, “Policing Human Trafficking.”

34Farrell and Pfeffer, “Policing Human Trafficking.”

35Adams et al., Evaluation of the Enhanced Collaborative Model to Combat Human Trafficking, Technical Report.

Please cite as

Greg Hall, David Gonzalez, and Richard Schoeberl, “Labor Trafficking Vulnerabilities and Victimization,” Police Chief Online, June 22, 2023.