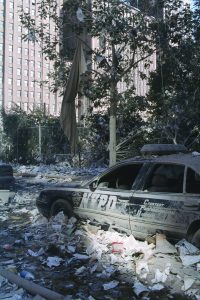

Joseph Esposito, the New York, New York, Police Department’s (NYPD’s) chief of department, was arriving at work on the morning of September 11, 2001, and about to drive through the entrance gate of One Police Plaza when the sound of the first hijacked plane hitting the World Trade Center’s North Tower reached him.

He looked up, saw the smoking hole in the building a few blocks away, and immediately started driving toward the complex.

By the time he reached the Battery Park underpass, where the FDR Drive bends around the southern tip of Manhattan, traffic had snarled to a stop. He ran the rest of the way to the World Trade Center. As he arrived at the site moments later, United Airlines Flight 175 crashed into the South Tower. He took out his department radio and issued a Level 4 mobilization—the single largest emergency deployment of police officers in New York City’s history—broadcasting to NYPD officers citywide, “This looks like a planned attack.”

Chief Esposito ordered the evacuation of NYPD’s headquarters, City Hall, the United Nations, the Empire State Building, and iconic signature buildings citywide, telling borough commanders across the city that they were on their own and trusting the leadership, training, and experience that he had helped inculcate in them to guide them as they put their respective emergency plans into effect. “I was on the job over 30 years at the time,” he says.

What are you going to do? A lot of it is common sense, but a lot is the result of training over the years, mobilizations responding to riots, blackouts, etc. For the police department, it is second nature.

Twenty years later, he is still quick to praise the actions of his colleagues that day. “Everybody who responded, they did a phenomenal job, and it was automatic…There wasn’t a lot of communication. But I knew that the people on the scene there knew what they were doing.”

After linking up with first responders from the NYPD Emergency Service Unit (ESU) when he arrived, he took shelter under an overpass across West Street, in the shadow of the Twin Towers.

I looked up and debris was coming down from over 100 stories up, bouncing all around us. When it stopped, I got out and threw my baseball hat on. The officers gave me a helmet, and I remember jokingly saying, ”Don’t lose my hat.” I went one way. They went another.

I watched the second tower melt. It was like a big candle, melting in fast motion… It was like Pearl Harbor, the civilian equivalent of that sneak attack.

The difference between Chief Esposito going one way and his colleagues from ESU going another turned out to be life versus death. He recalls,

Later that day, when I was with ESU again, I said to them, “You tell Vinnie Danz and Joe Vigiano I want my hat back!”… and their faces dropped. They knew both of them didn’t make it, and I hadn’t found out yet.

Salvatore Carcaterra, a retired NYPD deputy chief who managed the implementation of the department’s counterterrorism response to 9/11, recounts,

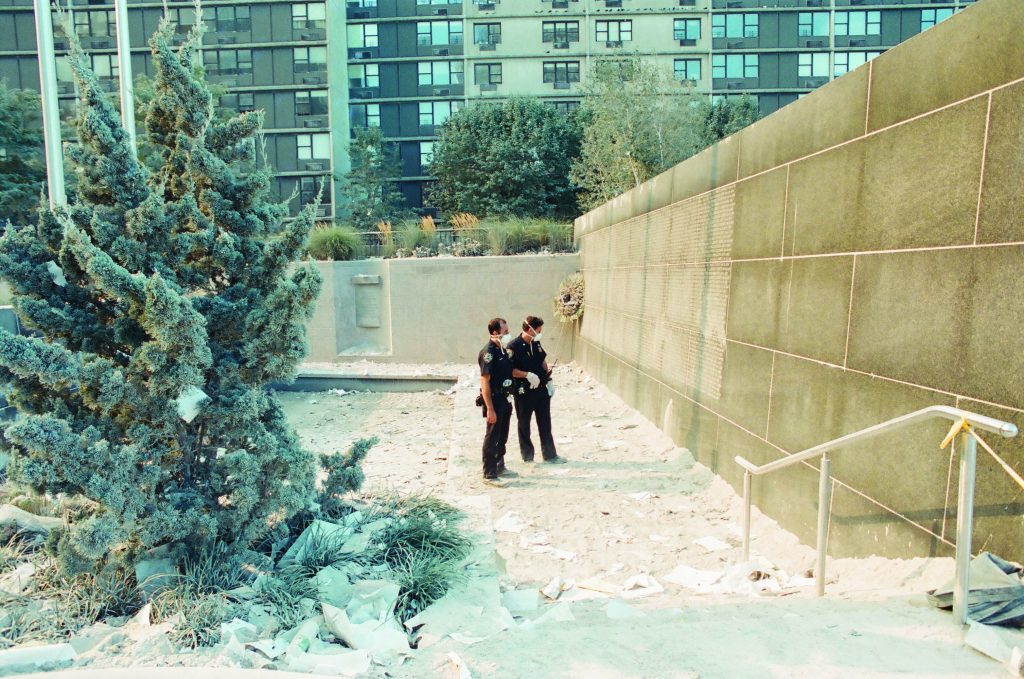

The South Tower is collapsing, and somebody grabs my arm and says, “Chief, the building is coming down.” We were under the overpass on West and Liberty—it was the only thing that saved my life. At first, we were getting hit like somebody throwing dirt on you, and then it just all came down hard, like a train. Things just went silent.

The emotion that he remembers is less fear than anger:

We were kind of buried, and I remember, personally, I was so angry at myself, thinking how the hell did I put myself in this position that I can’t get out of here, thinking I would die, that I couldn’t breathe… When the tower went down, it was just black… You were basically on your own figuring out how to survive.

Some of the officers, they were able to shoot the glass out [of the building they were backed up against], and we escaped to the other side near Battery Park. We started doing evacuations of people off Manhattan to New Jersey, back and forth via the harbor launch.

Thomas Galati, the NYPD’s longstanding chief of intelligence, describes running into a high-ranking official he knew that morning near City Hall after rushing to the scene from the 47th Precinct. He was told, “Get as many cops as you can find, go toward the towers, and try to help as many people as you can.” He remembers,

There were some cops around who were covered from head to toe in just ash, and I knew I couldn’t take them with me. They were there when the first tower went down. I gathered some other clean uniform[ed officers] and started making my way to the towers.

As Chief Galati and the officers approached, instead of the thicker and thicker crowds of people that they expected to see, they found empty streets:

The closer we came to the site, the less people there were. I was on Liberty and Church Street, and the ground was littered with all kinds of debris from the first tower—I vividly remember seeing a whole lot of shoes. Either people were blown out of their shoes, or ran out of them—they were everywhere.

“The sheer scale and unprecedented nature of the attack created insurmountable odds.”

Along with the shoes, Chief Galati vividly remembers the heat: “It was so hot where the building was that you couldn’t get close to it. You could literally walk over there and feel like you were walking into a fire.”

Carcaterra now serves as the executive vice president for Security Fire & Life Safety at the 9/11 Memorial and Museum, a job he feels called to do given his relationship to the site and to the events of the day. He emphasizes,

What we went through was nothing compared to the people hanging on the outside of those towers and knowing there was nowhere to go. That terror. Those people did not choose to jump. Open a 400-degree oven and feel yourself get burned—these fires were burning with jet fuel at 2,000 degrees. There was no choice.

Chief Esposito credits his colleagues with making many lifesaving decisions that day, such as a critical recommendation by the executive officer of Manhattan South to stage the NYPD’s incident command post farther from Ground Zero than initially proposed. But the sheer scale and unprecedented nature of the attack created insurmountable odds for first responders. The frustration and helplessness that many officers remember experiencing that day would form the basis of the counterterrorism program that the NYPD created, in order to never be in that position again. “As law enforcement officers, we know we are supposed to respond to this, but these people just went to work in the office,” Carcaterra explains.

On our side, just looking and knowing that we cannot help them, we just cannot get there—it was a horrible and helpless feeling. That’s a sound I will never forget in my entire life—those poor people coming down and hitting the floor, the ground… it was terrible.

He remembers, “Later that night, I don’t know what time it was, maybe two in the morning, I looked up at the helicopters and everything burning, and I just thought, ‘Where are we?’”

Making Sense of Our Despair: From Rescue and Recovery to Restructuring

Of course, 9/11 was not the NYPD’s first encounter with terrorism. The department had over a century’s experience dealing with politically motivated acts of violence, from investigating violent anarchist and communist entities with the NYPD’s Red Hand Squad to the 1993 World Trade Center bombing that presaged 9/11. The department had long dedicated resources to countering terrorism through its partnership with the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), a consequence largely born out of violent extremist bombings in the 1970s and 80s carried out by groups like the Weathermen Underground Organization, the Puerto Rican Fuerzas Armadas de Liberacion Nacional, Omega-7, and the Jewish Defense League, among others. The highly effective Joint Terrorism Task Force (JTTF) was the first dedicated federal/local partnership of its kind in the United States when it was established in New York City in 1980. But 9/11 left no doubt that the department couldn’t rely solely on its federal counterparts or existing partnerships and needed to fundamentally reimagine itself in order to protect the city. Even as the rescue and recovery effort at Ground Zero was ongoing, the NYPD, under the leadership of former Commissioner Ray Kelly, began to design within the United States’ largest municipal police force an intelligence-led, counterterrorism-focused capability that leveraged its specialized understanding of the local threat environment.

The immediate transformation within the department was equal parts evolution and creation. Commissioner Kelly appointed the new NYPD Deputy Commissioner of Intelligence David Cohen, who had recently retired from over 30 years at the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), where he served in senior positions in both its Directorate of Intelligence and its Directorate of Operations. Deputy Commissioner Cohen fundamentally transformed the NYPD’s Intelligence Bureau—which until that time had largely focused on protecting local officials and foreign dignitaries—into an entirely unique, counterterrorism-focused agency-within-an-agency that could anticipate, identify, and mitigate threats, wherever and whatever the origin. The bureau was reoriented toward intelligence gathering and bolstered with new investigative resources. Staffing was expanded and reimagined with the addition and redirection of seasoned investigators with years of experience fighting crime, as well as a new contingent of officers from international backgrounds, who brought with them critical language skills as well as deep cultural knowledge.

Commissioner Kelly also created the Counterterrorism Bureau (CTB) to complement the Intelligence Bureau’s ability to independently investigate and mitigate terrorism threats. After he was named as police commissioner by incoming Mayor Michael Bloomberg, but before taking office, Kelly met with some of his key advisors and sketched out the structure of the CTB on a sheet of butcher paper. The CTB would focus on hardening the myriad targets in and around the city, as well as responding to events ranging from a chemical or biological weapons attack to a radioactive dispersal device to a complex, coordinated active-shooter event taking place in the city.

These two bureaus, totaling some 1,000 men and women strong, formed the twin pillars of a counterterrorism strategy that would ably equip the NYPD to meet the threats that would confront it in the first two decades of the new millennium. Deputy Commissioner Cohen recalls a seminal conversation with Commissioner Kelly during one of the daily morning meetings in the early days of the program. “Someone asked him, what was the NYPD’s guiding strategy? He said, ‘Our strategy is to move the odds in our favor a little bit, every single day.’”

Tapping the Talent to Tackle the Threat: Leveraging the Diversity of Personnel

One of the earliest and best lessons that the NYPD learned was how to access the untapped resources that already existed throughout the department to leverage those law enforcement strengths established in nearly two centuries of policing. Key among these resources were officers from more than 160 countries who spoke 168 distinct languages. The diversity of the NYPD—whose personnel mirror the cultural melting pot of New York City and that became majority minority in 2006—differentiates it from even its federal intelligence and law enforcement peers. In the post-9/11 environment of growing transnational terrorism threats, diversity has become a defining strength.

Recognizing the urgent need to build subject matter expertise in the counterterrorism and intelligence space—institutional knowledge that federal agencies had the benefit of building over more than half a century—the Intelligence and Counterterrorism Bureaus recruited officers and analysts with critical language skill sets, overseas regional experiences, and backgrounds in international affairs. Commissioner Kelly worked with City Hall to establish new classifications and hiring authorities for civilian positions like intelligence research specialists, professional analyst roles based on those that existed for decades throughout the U.S. intelligence community. These men and women were recruited from established national security and foreign affairs graduate schools at institutes of higher education throughout the United States, as well as from agencies like the CIA, FBI, and National Security Administration and across the private sector. The teamed-up civilian analysts and uniformed investigators were charged with bringing their vastly different backgrounds, perspectives, and skills together to counter the terrorism threat. It has proved a formidable and enduring model.

The second key insight the department had was that no one knows the streets of New York City better than the officers who patrol them. The eyes and ears of roughly 36,000 officers, whether working in uniform, plainclothes, or in specialized undercover capacities, provided unparalleled domain knowledge and insight, which have become invaluable as the terrorism threat has shifted from external to homegrown. Conventional policing tactics and techniques—ranging from investigative experience with complex narcotics cases, to covert work in plainclothes street crime and anti-crime units, to comfortable familiarity talking to, recruiting, and running sources—formed the backbone of the human intelligence–based work that the Intelligence Bureau soon became defined by. Given NYPD’s decades of experience working with sources of information from different communities to combat crime, it was natural for the Intelligence Bureau to create units to apply the same techniques and expertise to combating terrorism. The cornerstone of the bureau’s human intelligence capabilities was a deep undercover program that had already existed for nearly a hundred years.

“No one knows the streets of New York City better than the officers who patrol them.”

This approach served equally useful in addressing crime. The Field Intelligence Officer (FIO) program, comprising uniformed members of service serving in each of the city’s 77 precincts, housing police service areas, transit boroughs, and other specialty locations throughout New York City, is a key example of this approach. FIOs track down hundreds of illegal guns each year, develop leads online, and debrief individuals who may have valuable information about terrorism-related or criminal activity. They seek to prevent gang and crew violence as well as terrorism. They provide a mechanism for the Intelligence Bureau to understand the crime trends afflicting the city as well as communicate information related to terrorism down to the precinct level.

New Threats Meet New Tech: Leveraging the Power of Data

The devastation of 9/11 didn’t just result from a failure of imagination; it laid bare multiple failures of technology. The list of things that went wrong was long and varied, compounding the sheer enormity of the destruction. Interoperable gear, equipment, and technology—from radios, repeaters, and mobile telecommunications kits to respirator masks and other personal protective equipment—were minimally available and hardly functional. The 911 call systems, according to the findings of the 9/11 Commission Report, struggled to manage the volume of calls and were limited by dispatching operational procedures.1 Mobile phone networks were heavily impacted from the damaging combination of a destroyed cell tower infrastructure and surges in wireless communications traffic. Twenty years later, the technological infrastructure is much stronger. The NYPD, FDNY, PAPD, and other partners rely on far more resilient and interoperable communications platforms with a greater number of cross-band UHF radio communication channels that can be accessed by shared-mission responders in an emergency. Inter-connected operating protocols like the Department of Homeland Security–guided National Incident Management System, innovative joint operations centers, and interagency tabletop exercises, ensure that incident plans are coordinated and enacted with partnerships at the center of crisis response.

The 9/11 attacks also transformed the way the NYPD used the vast amount of data that it generated. The NYPD has considered itself data driven since the 1990s, when Commissioner William Bratton drastically reduced citywide crime with the CompStat program. At that time, the technology involved wasn’t much more sophisticated than pushpins on a map. After 9/11, the department invested heavily in the creation of centralized data repositories and powerful engines to search them, bringing the philosophy of CompStat into the information age. The goal of these efforts wasn’t just to centralize data, it was to democratize it—the latter being nonobvious in a paramilitary institution.

Multiple streams of data, which had previously existed in silos that were not even always electronic (forms in triplicate being a signature of the department well into the 2000s), were fed into broadly accessible lakes of information and made available not only to executive-level decision makers in police headquarters, but also to patrol cops on the street. Department-wide data collection and analysis programs such as the Domain Awareness System (DAS), the license plate reader expansion, and the vast camera network of the Lower Manhattan Security Initiative (LMSI) have, in recent years, transformed the work of uniformed members of service throughout New York, allowing them to access torrents of valuable information for situational awareness, incident response, and investigative purposes. All of this information, moreover, is accessible via their department-issued smartphones and tablets.

Many of the NYPD’s most advanced technological platforms, initially developed and funded for a post-9/11 counterterrorism need, also demonstrated value and applicability in combating crime. GPS-derived automatic vehicle location and identification systems that enable the NYPD to monitor the movement of its patrol resources in real time help with large mobilizations as well as identifying, monitoring, and patrolling hot spot areas of crime. The same video camera networks originally established to help identify suspicious activity and unattended packages on the city’s more than 200 miles of mass transit lines also regularly prove essential in identifying suspects of violent crimes throughout the subway system. Even something that seems so simple today—a police officer having access to a department-issued smartphone—allows the department to transmit tactical intelligence products, situational awareness reports, and be-on-the-lookout notices (BOLOs) for real-time officer safety, incident response, and suspect identification and apprehension purposes.

Succeed Together or Fail Alone: Global Networks of Local Law Enforcement

When teams of assailants arrived by boat in the city of Mumbai, India, to attack multiple hotels and a religious center over three fraught and deadly days in 2008, some of the first foreign law enforcement agents to arrive on scene were a team of officers from the NYPD. The NYPD’s International Liaison Unit post, stationed in Amman, Jordan, arrived on scene within 72 hours of the attacks, working with local and international law enforcement personnel to understand the scope and impact of what had happened. Within a few days, the NYPD team on site called in from Mumbai to a packed auditorium at NYPD headquarters, briefing NYPD’s leadership cadre and key private sector security directors about what had happened. Before the chaos in Mumbai had subsided, New York City stakeholders were already beginning to prepare to protect their assets from a similar attack.

While 9/11 required seismic adaptions of the NYPD, the department drew as much from the experiences of other departments and cities in dealing with terrorism as its own. Among the most valuable lessons of the post-9/11 era was the imperative for relationship building. Lieutenant John Miedreich, who marks 20 years with the NYPD this year, was part of the “9/11 Class,” the group of police academy recruits who were put into the field ahead of graduation to support the demanding security needs of the city in the early days after 9/11. Today, he leads the Intelligence Bureau’s International Liaison Unit (ILU), which includes 14 overseas and 3 domestic liaison posts that are embedded in local law enforcement or international policing agencies. These specialized liaisons, unique among major municipal police agencies in the United States, provide firsthand daily reporting to NYPD decision makers, allowing the department to ask what Commissioner Kelly referred to as “the New York question” when a high-profile incident takes place elsewhere. Though the liaisons do not independently conduct international investigations, they serve as vital interlocutors—they are able to learn best practices, provide counsel, and share critical information in real time by speaking the language of law enforcement. Forging sustaining relationships with other agencies allows crucial intelligence to be analyzed and targets to be hardened back home in New York City. While the primary remit of ILU is counterterrorism intelligence, the NYPD’s overseas liaisons have supported international partners on a range of criminal matters, from recovering a missing person from the UK to bringing home evidence in a European artifact-smuggling case to greeting a homicide suspect from New York City with an arrest warrant in Bangkok, Thailand.

Building off the success of the ILU, the Intelligence Bureau created Operation Sentry in 2006—a nationwide domestic network of more than 670 trusted law enforcement partners throughout the United States. This partnership program—which grew from a small network of police allies primarily in the tristate area called the Strategic Intelligence Unit—acts as an intelligence force multiplier that collaborates to produce and disseminate tactical and strategic intelligence products, support domestic partners during major incidents, and mutually assist with investigative efforts across all 50 U.S. states. As with many of the bureau’s programs, its creation was inspired and driven by a specific incident. On July 7, 2005, London, England, experienced its version of 9/11, when four suicide bombers killed 52 people on the subway and a bus. The 7/7 attacks, as they were known, were not planned in London, but some 200 kilometers away, in the city of Leeds.2 Similarly, the 1993 World Trade Center bombing had been planned across the river in New Jersey. It was clearly necessary to expand the NYPD’s defensive security perimeter beyond the five boroughs and establish clear lines of communication and mutual support among regional law enforcement partners.

As the Intelligence Bureau stood up ILU and Operation Sentry, the Counterterrorism Bureau invested considerably in interagency partnerships by bolstering its personnel contributions to the JTTF, moving from only a handful of detectives pre-9/11 to more than 100 assigned today. The NYPD also enhanced existing partnerships with the New York/New Jersey High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area (NY/NJ HIDTA), enabling its uniformed and civilian personnel to work in the same spaces as personnel from more than 30 state and federal agencies, which were all becoming increasingly integral to the United States’ new homeland security mission.

Collectively, these expanded networks of support have allowed the department to learn from incidents elsewhere—such as the deadly 2004 Madrid, Spain, train bombings; the November 2015 Paris, France, attacks; and the May 2017 Manchester Arena suicide bombing in the UK—how to better protect New York City.

An Informed Public: An Instrumental Partner

The NYPD realized early on the power of the public to be a force-multiplier and a tripwire. By launching a simple way for members of the public to call in leads via a 24/7 hotline, the Intelligence Bureau created an early warning system for attack planning and preparation. The post-9/11 “If You See Something, Say Something” campaign, originally created by the New York Metropolitan Transportation Authority and later licensed by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, has become a part of ordinary life in New York City over the past 20 years. The Intelligence Bureau, independently or in coordination with the JTTF, investigates every lead called in, with approximately 900 leads processed every year.

In addition to being informed by the public, the NYPD takes seriously its mandate to help inform the public. Through specially tailored public-private partnerships like Operation Nexus, the Intelligence Bureau engages with private sector stakeholders in tactically significant industries—such as purveyors of potential explosives precursors, pyrotechnics, or commercial chemical and infrastructure companies—to help them better understand how to detect anomalous activity. In the aftermath of the deadly vehicle-ramming attacks in Nice, France, and along the West Side Highway’s Hudson River Greenway in Manhattan, members of Operation Nexus visited dozens of truck rental businesses to give them information about what had happened and make sure they knew who to call if they saw something themselves. Through CTB’s SHIELD program, the Intelligence Bureau disseminates intelligence products to more than 20,000 public and private sector entities, providing them with training, briefings, and a network through which they can become better able to protect themselves and each other. SHIELD’s commitment to this work helped lead to the creation of similar local intelligence sharing programs by more than a dozen law enforcement agencies throughout the United States and Western Europe.

NYPD Deputy Commissioner John Miller maintains, “Buying equipment, developing LMSI, the Domain Awareness System, the license plate readers, the network of cameras, all of the things that became our concentric rings, our layers of counterterrorism protection, was an enormous investment.”

Equally important was the department’s investment in relationships. Miller underlines,

Part of what we learned from 9/11 was that we have to share information and that comes with trust. That trust comes with relationship building that cannot be done on the day of the attack.

Relationships are built under non-stressful circumstances so that during stressful circumstances you have a lot of friends around who are ready to help… The return value of the surrounding security that comes with those partnerships and those layers and levels of trust cannot be calculated or estimated… it’s extraordinary.

The dividends of those regional relationships were paid in September 2016, when Ahmad Khan Rahimi, a Salafi-jihadist extremist, detonated pipe bombs and pressure cooker IEDs in Seaside Park, New Jersey, and Manhattan’s Chelsea neighborhood. Within 50 hours of the first explosion, Rahimi was identified as the sole suspect, made the focus of a BOLO alert that was widely disseminated to law enforcement partners, and ultimately discovered and taken into custody after a firefight with officers of the Linden, New Jersey, Police Department.3 This partnership triumphed across multiple local, federal, and state agencies and across state lines.

Building the Legal Architecture to Support the Mission

Prior to 9/11, local law enforcement authorities across the United States were well positioned to respond and investigate criminality after an incident took place—responding to crime scenes, collecting evidence, and interviewing witnesses—but they lacked the proper legal foundation for increasingly essential preventative actions that required weeks, months, and even years of complex investigative work. Policing in the post-9/11 era that seeks to be proactive rather than reactionary hinges on having appropriate legal policy to guide these investigations. Having a defined and understood legal structure ensures the flexibility to act before a terrorist attack occurs and gives guidance for the level of intrusive measures permitted as an investigation progresses, while protecting civil rights and liberties.

In 2003, the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York modified a consent decree that the NYPD had been operating under since 1985, which placed certain constraints on the investigation of political and religious activity. The modification, requested by the NYPD to provide the department more latitude to investigate potential terrorism, provided more leeway to focus on preemptive investigations and wrote into law a series of guidelines that would govern these investigative activities. Called the Handschu Guidelines, these rules are the legal backbone of the Intelligence Bureau’s work.4

The balance between security and privacy has been tested over the past two decades, and the department has continued to adapt, creating policy and practice that keep up with the threat and the law, while preserving core constitutional norms and democratic values. In 2017, the department settled two federal cases dating from 2013 that sought to change the practice of how terrorism investigations are carried out. The settlement enhanced the Handschu Guidelines by enshrining as law certain practices that had been taken voluntarily related to its investigative practices, requiring the consideration of the least intrusive methods for collecting information and, importantly, establishing external civilian oversight.5 The presence of an external, objective, civilian representative on the committee responsible for administration of the Handschu Guidelines has been invaluable—providing a multiplicity of views while avoiding groupthink and being a credible bridge between the bureau and the many communities that it serves.

Prevention, Preparedness, and Response: Creating and Growing the Counter-terrorism Bureau

Since its genesis on butcher paper in the immediate wake of 9/11, the Counterterrorism Bureau has been responsible for the “deter” and “defend” pillars of the NYPD’s response. The CTB has made vigilance against acts of terrorism not merely an add-on consideration for major events like New Year’s Eve and the New York City Marathon, but rather its daily mission. One of the most recognizable units of CTB is the Critical Response Command (CRC), a unit of more than 500 officers who surge to critical infrastructure sites, iconic landmarks, and sensitive locations throughout the five boroughs, guided every day by the most up-to-date threat intelligence. While the development of the CRC was years in the making, it was first deployed citywide in November 2015, in the immediate aftermath of the Paris attacks that left 130 dead and more than 450 wounded.6 The multiphased suicide bombing, gunfire, and hostage-taking attack was the deadliest act of peacetime violence in France’s history and, for the NYPD, drove home the urgent importance of the NYPD having its own rapidly deployable, heavily equipped, and specially trained capability to respond to a similar complex, multisite, mass casualty attack.

Through regular intelligence-led pre-deployment of assets, the NYPD strives to reduce the number of vulnerable “soft targets” throughout the city by hardening key locations of concern, thus achieving deterrence through defense. When the average New Yorker encounters an NYPD transit bag check in a packed station at rush hour, or a STRYKER team of heavily armed CTB officers deployed to an iconic venue, or a Vapor Wake Explosive Trace Detection K9 unit scanning outside a crowded parade, they are seeing firsthand the impact of CTB’s creation. Complex protective counterterrorism overlays that involve detailed pre-event security threat assessments, infrastructure-hardening countermeasures like vehicle barriers, and extensive uniformed and plainclothes force deployment plans are now developed as a matter of course for virtually every major event in New York City, from parades and papal visits to the Super Bowl to the annual United Nations General Assembly. Guided by intelligence obtained from liaison posts overseas, partners across the United States, and assessments from the analytical cadre in New York City, each day, counterterrorism-trained, heavy weapons–equipped CRC teams deploy at locations of potential elevated threat throughout New York City’s five boroughs. They harden vulnerable locations, deter the hostile preoperational surveillance efforts of adversaries, and provide public assurance of rapid response to an incident.

Far Ahead Yet Front of Mind: Anticipating Future Attacks

The attacks of 9/11 were the sum total of a series of systemic and structural shortcomings, but perhaps one of the greatest culprits was the failure of imagination. No one imagined an attack of this scope or scale. As the NYPD and its partners look to the future, they still find themselves grappling with threats from the past that shape the present. Since 9/11, at least 44 publicly known plots and attacks have targeted New York City. These plots have varied dramatically over the years in terms of complexity, sophistication, and ideological drivers, but the goal of inflicting casualties on the streets of New York has remained constant. Moreover, the pace of the plotting and attacking has increased markedly over the years—half of the incidents took place in the last five years alone. The diversification and acceleration of the plotting against the city have required sustained efforts to defend it.

Despite significant leadership losses, organizational fracturing, and territorial degradation, foreign terrorist groups like al-Qa’ida and ISIS remain a persistent challenge, consistently threatening New York City in extremist recruitment and tactical training propaganda distributed via online channels and encrypted messaging platforms. While low-tech attacks involving edged weapons, vehicle rammings, and small arms may seem like the order of the day, the consistent tactical interest in improvised explosive devices and more sophisticated mass casualty assaults has not dissipated, as the failed suicide bombing in the subway below the Port Authority Bus Terminal on December 11, 2017, makes clear.7

The deadly December 2019 mass shooting at U.S. Naval Air Station Pensacola highlighted the enduring influence of a patient adversary—al-Qa’ida’s affiliate network in Yemen. Just last year, the public disclosure of a disrupted terrorist plot in the Philippines that was orchestrated by the same group’s East African affiliate al-Shabaab, again demonstrated that the fixation on 9/11-scale attacks remains as real today as two decades ago. Were it not for the persistent effort and swift intervention of U.S. intelligence and law enforcement authorities in that case, the world could have again seen a skyscraper in the United States attacked with a hijacked and weaponized passenger airline.

Separate and apart from these now familiar foreign terrorist organizations and the homegrown Salafi jihadists they inspire is a bourgeoning domestic violent extremism problem composed of racially and ethnically motivated violent extremists and anti-authority anarchists that will add to the challenges faced by U.S. law enforcement. In 2019, with a series of domestic terrorism incidents from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, to Poway, California, and from Charleston, South Carolina, to Christchurch, New Zealand, demanding greater law enforcement attention and focus, the NYPD established a task force dedicated to racially and ethnically motivated violent extremism (REME), expanding resources within the department and collaborating with other agencies to address this growing threat. In the aftermath of the January 6 Capitol Riot, the perception among some of a permissive environment for targeted violence against political figures not only adds fuel to the fires of stochastic terrorism but also makes the fine line between constitutionally protected speech and dangerous deliberate threats even more challenging to discern.

Regardless of the ideological drivers of the threat, the program that the NYPD created in the aftermath of 9/11 can address it using the same tools and techniques it deploys to combat terrorism that originates overseas. In a post-9/11 world, the NYPD stands ably equipped to establish new units, move teams, and reallocate resources to match the threat as it shifts.

In the 20 years to come, these threat actors will likely become increasingly difficult to define, with ideologically untethered, violent, lone individuals drawn to the act of mass bloodshed as a personal means of self-actualization and driven more by a myriad web of personal grievances, conspiracist views, and catalytic events than by a specific political agenda or worldview. Technological advancements will continue to change the nature and course of potential threats, with implications for unattributable hostile nation-state violence via proxy. Threat domains ranging from cyber malware to 3D printed weapons to remotely piloted aircraft, along with advances in machine learning, quantum computing, and encryption will continue to change the environment.

Above all, in a world where the virtual is often indistinguishable from reality, the lag time between concerning rhetoric and violent action can be shorter than ever before. The critical task for law enforcement will be to operate in the now, while never taking an eye off the later—prioritizing strategic threat assessments, intelligence analysis-led national security initiatives, and tabletop exercises that provide opportunities to anticipate and prepare for the next era of threats.

Born from Tragedy: A Legacy of Protective Service

Twenty years later, the NYPD continues to learn and grow, but it also continues to suffer from the single deadliest act of terrorism ever perpetrated against the United States. At least 274 NYPD members and 252 FDNY firefighters have died since 9/11 from cancers, cardiovascular disease, and other severe illnesses contracted as a direct result of their service and sacrifice at Ground Zero—conditions that have left many of them at even greater risk amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Scores more struggle silently with post-traumatic stress disorder. As of this year, there are 110,198 survivors and first responders registered in the World Trade Center Health program, which monitors and treats those at risk and battling diagnosed 9/11-related illnesses. Those lost are held in the memories of members of the NYPD, FDNY, and PAPD, who can recall attending more funerals in those first few months after 9/11 than most people endure in a lifetime. The resilience of those who grieved and coped with the loss of coworkers, family, and friends, while spending weeks and months protecting and working at the site of their final moments is still palpable in today’s NYPD. However, the pain of 9/11 also compounds for many as the years pass and the stacks of funeral prayer cards on desks grow taller with each fallen officer who succumbs to the lingering consequences of that terrible attack and its toxic aftermath.

On the 20th anniversary of 9/11, officials, first responders, victims’ family members, and scores of people from around the world will gather in the fields of Somerset County, Pennsylvania; at the Pentagon in Arlington, Virginia; and at the World Trade Center site in Lower Manhattan to once again pay their respects, remember, and reflect on how much has changed in two decades. At the 9/11 Memorial in New York, there now rests a new addition to the solemn site known as the Memorial Glade, which was dedicated in 2019 to the thousands of emergency first responders, laborers, survivors, and volunteers from across New York City, throughout the United States, and around the world who came to help this city in its hour of greatest need. The Memorial Glade honors these brave men and women—those who, as the dedication inscription reads, “renewed the spirit of a grieving city, gave hope to the nation, and inspired the world.”

After one of the most harrowing years in recent memory, this powerful symbol is needed more than ever, though no stone or steel monument will ever be a fitting enough tribute to those public servants’ lives and the nearly 3,000 souls taken on that clear September morning. May the shared commitment at the NYPD and at countless first responder agencies—to live by their example, to be defined by response and recovery, not by ruin—help to build a living and forever enduring memorial of service to all who were lost.

|

John Tully Gordon is an intelligence research specialist with the NYPD Intelligence Bureau where he serves as the team leader for the Global Trends and Developments unit, responsible for providing timely, accurate, and actionable intelligence analysis on national security issues and terrorism-related threats. He began working for the NYPD in 2010. |

|

Assistant Commissioner for Intelligence Analysis Rebecca Ulam Weiner manages counterterrorism and cyber intelligence analysis and production for the NYPD’s Intelligence Bureau. She is one of the principal advisors to the deputy commissioner of intelligence and counterterrorism, and she shares responsibility for bureau-wide policy development and program management. |

Notes:

1 National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States, The 9/11 Commission Report: Final Report of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 2004).

2 “7/7 London Bombings,” Sky History.

3 “Ahmad Khan Rahimi Sentenced to Life in Prison for NY Bombing,” BBC News, February 13, 2018.

4Handschu v. Special Services Division, 288 F.Supp.2d 411 (S.D.N.Y. 2003).

5 Handschu, 288 F.Supp.2d 411; Raza v. City of New York, 998 F.Supp.2d 70 (E.D.N.Y. 2013).

6“2015 Paris Terror Attacks Fast Facts,” CNN, November 4, 2020.

7Sarah Maslin Nir and William K. Rashbaum, “Bomber Strikes Near Times Square, Disrupting City but Killing None,” New York Times, December 11, 2017.

Please cite as

John Tully Gordon and Rebecca Ulam Weiner, “Light Pierces Through: An NYPD Reflection on Loss & Lessons Learned 20 Years after 9/11,” Police Chief 88, no. 9 (September 2021): 34–53.