Imagine for a moment the typical calls for service related to drone activity that are occurring in cities across the United States. Dispatch is notified of a drone flying very close to a crowd gathered to watch a local sporting event. Two patrol units are directed to the approximate location where the drone was last seen. The officers observe a drone flying above a large crowd, but the pilot cannot be located. The officers also observe something hanging from the underside of the drone, but they cannot immediately discern what it is.

How are officers trained to respond in this scenario? How will officers respond?

-

- What efforts do the officers use to locate the pilot? (A random search? A grid search?)

-

- How do the officers react to the unknown payload beneath the drone?

-

- Is this a nuisance flight by an uneducated pilot, or a credible threat to public safety by a nefarious actor requiring immediate action?

-

- Does the agency have the most up-to-date tools at its disposal to deal with any drone situation in its city or town?

-

- Is the agency or officers able to detect and locate both the drone and the pilot?

-

- Can the agency classify this drone (manufacturer, model, pilot identity)?

-

- Can it effectively deal with the incident at all (interdict the pilot; educate and/or cite; or legally mitigate/counter with appropriate federal partners)?

| Figure 1: How would officers respond? How are they trained? |

|---|

|

Increasing Presence of UAS

Drones have become immensely popular in recent years due to their versatility, low cost, and uses in various industries. Drone acquisition and use by police agencies has also grown in recent years. With programs such as Drones as a First Responder (DFR), drones have proven to be a force multiplier, supporting quicker and safer missions, traffic accident reconstructions, criminal investigations, and tactical overwatch during field operations.1 Across the United States, model examples are now emerging on how best to employ this advanced technology to enhance public safety and to ensure the well-being of police personnel. And policing’s use of drones is likely just the beginning of this new paradigm. However, agencies are also learning that the other side of that same coin is the new threats that drones pose as well.

The increasing use of uncrewed aerial systems (UAS) by the public have led to tangible threats to the safety of others, ranging from nuisance activities such as unwanted or illegal surveillance of civilians and interference with public events, to more grave hazards such as aerial conflicts with crewed aircraft, delivery of contraband to prisons, illegal drug shipments, and the ultimate concern—terrorism.

Just as there are rules of the road when driving a car, there are rules in the sky when operating a drone. In summary, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) regulations require that drone pilots abide by the following rules:

-

- Avoid manned/crewed aircraft

-

- Never operate in a careless or reckless manner

-

- Fly only during daylight or in twilight with appropriate anti-collision lighting

-

- Keep the drone within sight (Do not fly beyond visual line of sight [BVLOS])

-

- Do not fly over 400 feet above ground level (AGL)

-

- Do not fly over 100 miles per hour (87 knots)

-

- Do not fly a small UAS over anyone who is not directly participating in the operation

-

- Do not fly from a moving vehicle unless you are flying over a sparsely populated area

-

- Follow the rules for flights within Class B, C, D, and E airspace, and get prior air traffic control approval when required2

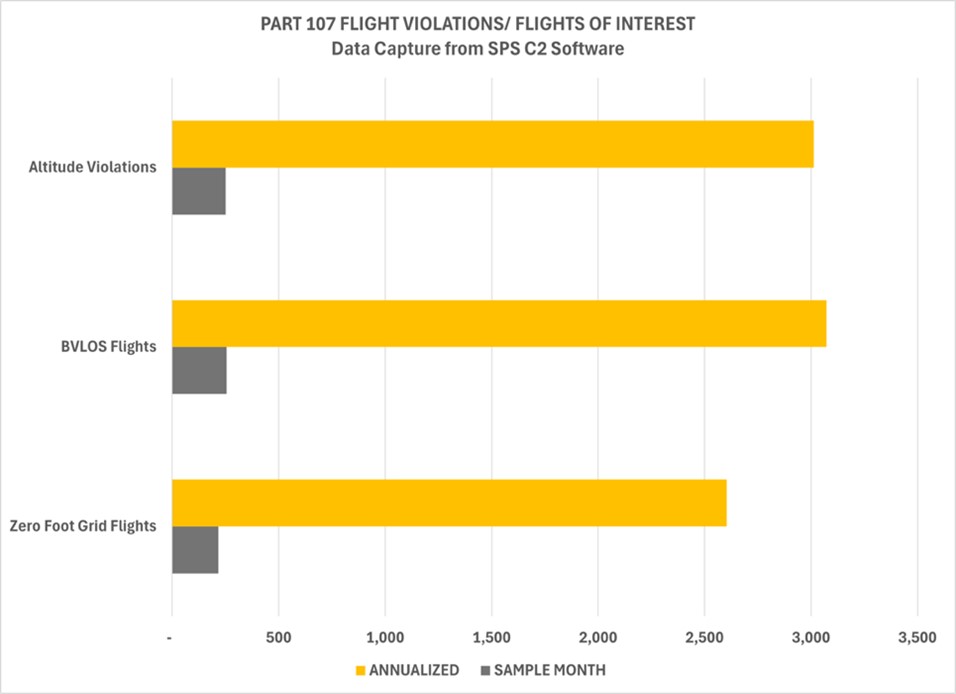

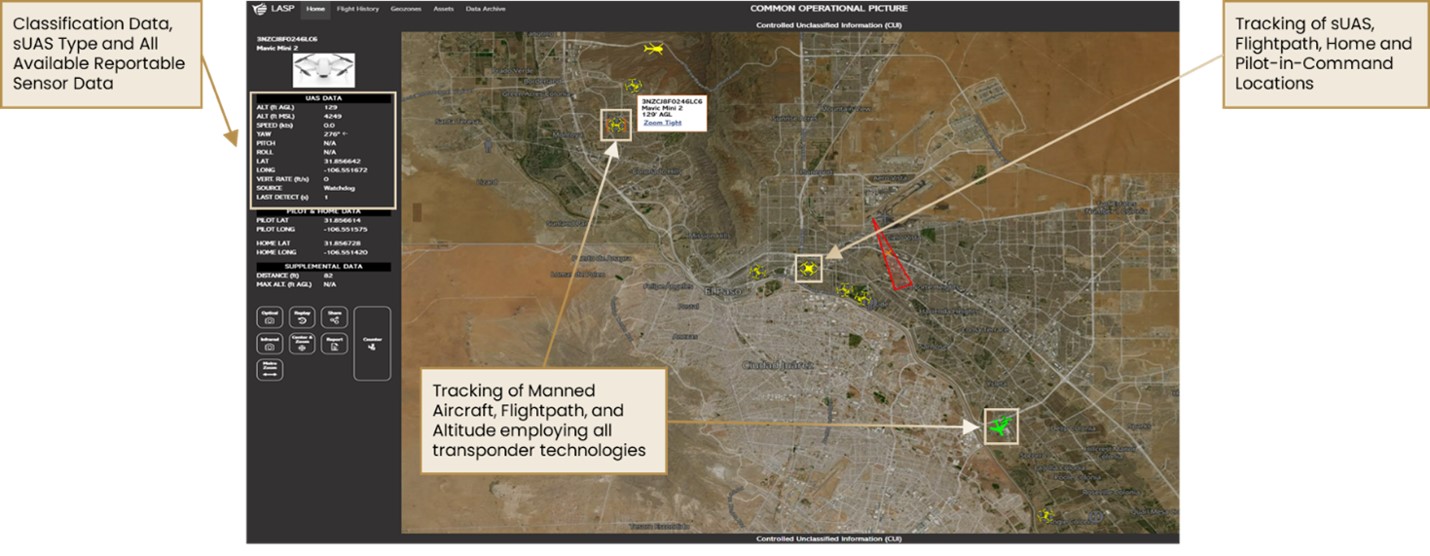

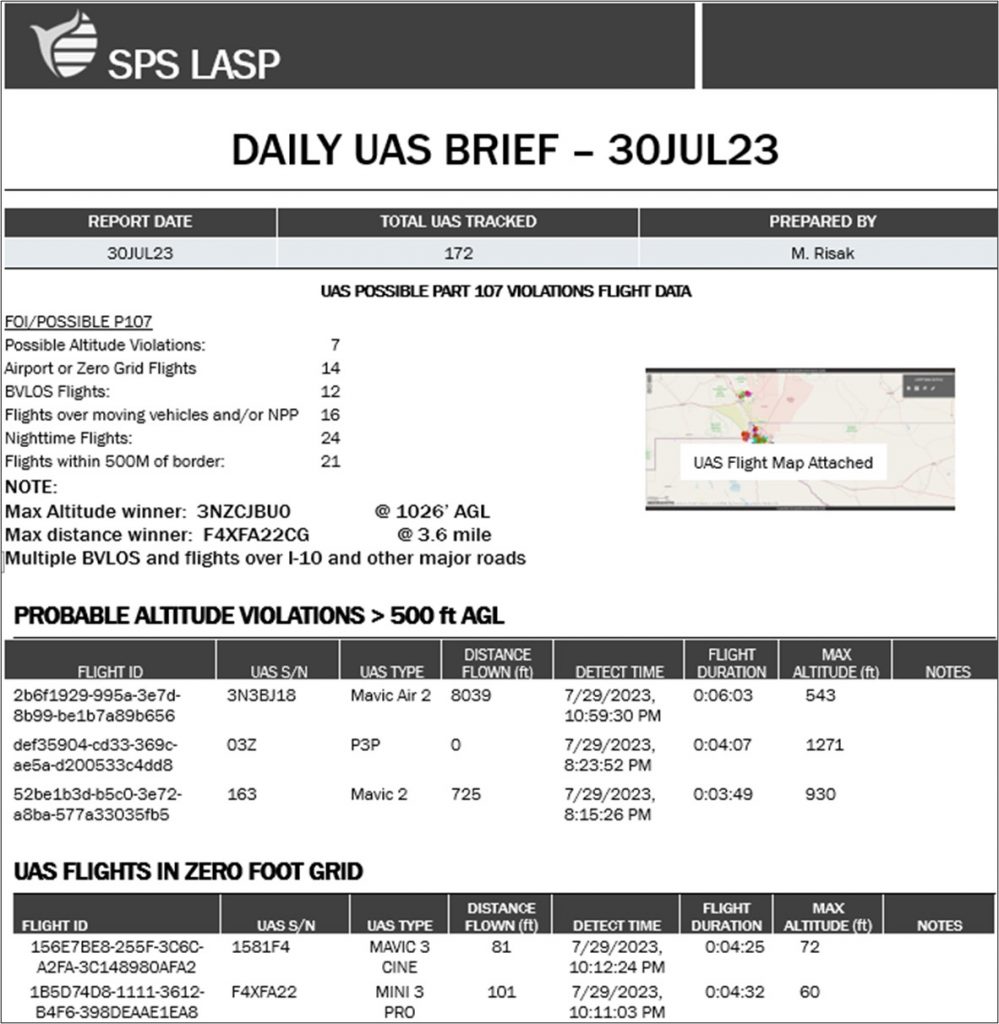

The fact is that there are an astounding number of UAS flights every day, in every city, that violate at least one rule of the FAA’s UAS regulations. This can be illustrated by examining what is occurring daily over the metropolis of El Paso, Texas, a city that, since 2021, has been leading the way for UAS-sensing technologies. Here, every drone and low-flying aircraft is subject to a robust monitoring system, and, within a typical month, Part 107 violations occur frequently. The violations that occur most often include flying beyond visual line of sight, flying in excess of 400 feet AGL, and flying illegally in certain classes of airspace (including “zero-foot grids where drone flights require special permissions”).3

| Figure 2: Typical violations, as seen over El Paso, Texas (SPS-ARS) |

|---|

|

The risks posed by these stealth dangers are nearly invisible to the public’s consciousness. To date, the police have been incapable of countering these risks as well, most notably due to competing missions, limited budgets, and time constraints. This has led to inaction and inattention when trying to derive solutions to deal with not only drones but all low-altitude aircraft over a particular airspace.

But a few forward-thinking police leaders have been very active in planning for and confronting this growing threat.4

Leveling the Playing Field

Previously, the solutions and tactics to deal with UAS incidents were elusive, and the hardware and software required to address these threats were prohibitively expensive. However, as of March 2024, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) has implemented new regulations to assist in the investigation of drone incidents, known as Remote ID (RID). This new policy requires (1) registration of drone ownership and (2) broadcasting telemetric information that enables police agencies to detect and track drone and pilot locations.5 Today, this “tier-one” RID solution, which includes sensing hardware and detection software, now costs a fraction of what it did previously.

A more robust solution has also been recently developed to confront the hazards posed to public safety by UAS: implementation of a wide-area, low-altitude aircraft monitoring system. The police now have access to the basic tools to detect, track, and identify drones in real time and to confront, educate, or cite individuals operating in dangerous or unlawful manners. This solution can be installed in various configurations to cover any area deemed important and critical to public safety, such as a popular sporting event in a confined footprint, a portion of a city or town that contains its most critical infrastructure, or the most advanced solutions that cover an entire city. And with the inclusion of local, state, and federal law enforcement partners working together in a unified manner, it is now possible to effectively mitigate the emerging threats posed by drones.

Threat Profiles

UAS nuisance activities, including unwanted or illegal surveillance of individuals

One of the most prolific threats posed by UAS activity is drone pilots who conduct unwanted or illegal surveillance of individuals. The ease of acquiring and operating low-cost drones and their use at any time of the day or night in a manner that is still largely unmonitored has raised concerns about the potential for privacy invasion. Unauthorized drone operators can and have used UAS to invade private property or gather personal information, leading to allegations of abusive behavior or worse, criminal harassment.6 The ability of UAS devices to capture high-resolution images and record videos raises additional concerns.

Public safety hazards from malfunctioning UAS

UAS malfunctioning while in flight adds another layer of risk to public safety. Whether through technical glitches or operator errors, drones have fallen from the sky, endangering people and property below. An uncontrolled descent of a drone can (and has) caused impact injuries or damage to buildings, especially in crowded areas or near critical infrastructure.7 Manufacturers have made efforts to prioritize safety features, and operators are encouraged to employ stringent maintenance standards to minimize the risk of accidents caused by drone malfunctioning, but mishaps and injuries have occurred. And the numbers of failures are certain to increase as more drones are added to the airspace.

UAS interference with public events

UAS interference with public events, such as during sporting events or concerts or over any large gathering of people, can disrupt and pose hazards to the general public. This was most recently seen during the NFL playoff game in Kansas City, when the game was suspended as an unauthorized drone flew over the stadium.8 The unauthorized operation of drones over crowded spaces can result in reactions from annoyance to panic, as spectators may fear a real or perceived threat. To mitigate this risk, event organizers and security personnel can opt to implement strict no-fly zones and deploy effective counter-drone point-solution measures but only when working with federal law enforcement partners.

UAS conflicts with crewed aircraft, especially helicopters or airport operations

Perhaps one of the most dangerous threats currently posed by UAS is their potential for conflicts with crewed aircraft, particularly helicopters and commercial airliners. Even small drones can cause significant if not catastrophic damage to crewed aircraft, potentially jeopardizing the safety of passengers onboard and those on the ground.9 Incidents of near misses between drones and aircraft have increased, highlighting the necessity for more diligent enforcement of regulations, better anti-collision technology, and enhanced UAS pilot training. This type of conflict has already been witnessed in the following instances:

Aircraft on Approach and in Departure—Recognized as a grave hazard by the FAA, airports have been researching UAS-sensing solutions; however, most airports have yet to effectively mitigate these threats.

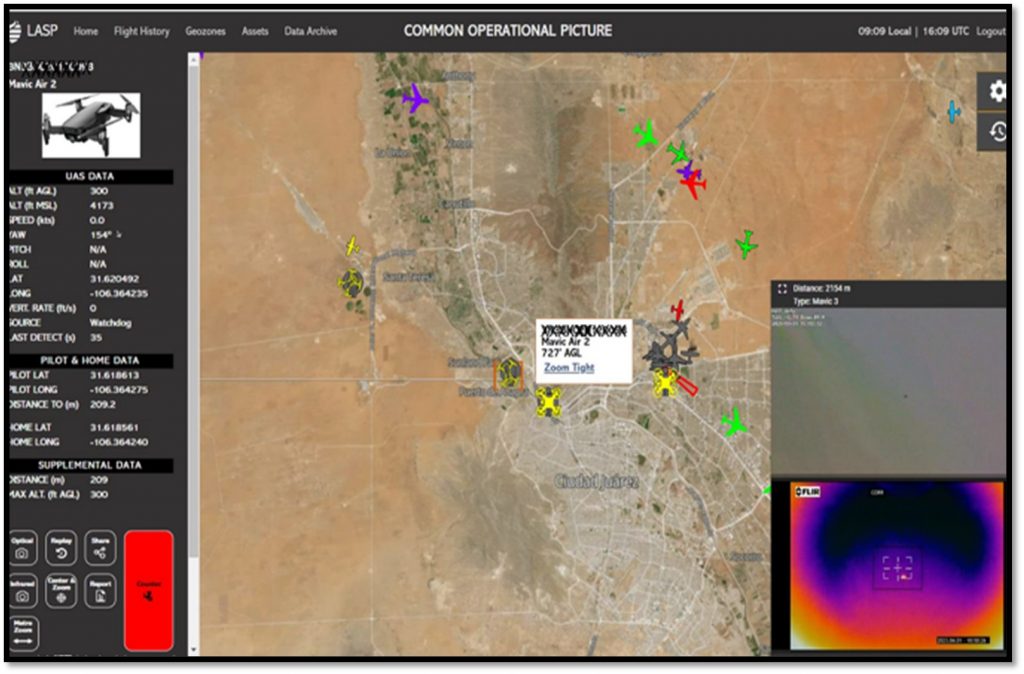

Air Ambulance Operations—Helicopters performing medical support operations often fly at low altitudes and at high speeds. UAS and helicopter near misses have been observed but are difficult to document. However, one such incident in April 2022 was captured and recorded by SPS-Aerial Remote Systems (SPS-ARS), a company based in El Paso, Texas, that specializes in UAS detection, classification, and countersecurity solutions. A “near miss” occurred when the helicopter flew underneath a UAS at a separation range of less than 100 feet. 10

| Figure 3: Screen shot from the SPS-ARS Common Operating Picture (COP) of the April 2020 “Near Miss.” |

|---|

|

Fire Department Air Operations—Aerial firefighting operations are often utilized for high-rise fire support, in hoist rescues, and during wildfires. Drones have interfered with the safe operation of aircrews fighting the fires, necessitating the air boss to halt all operations until the UAS has departed the area.11 The cessation of air assets at a critical time in the firefighting operation has had detrimental consequences to fighting wildfires.

UAS usage for delivery of contraband to prisons

The usage of UAS for the delivery of contraband to prisons represents a growing menace to the security of correctional facilities. Criminals have exploited drones’ capabilities to transport illicit items, such as drugs, weapons, or mobile phones into prison compounds.12 Implementing counter-drone measures and creating no-fly zones around correctional facilities are crucial steps in combating this threat, but illegal drone activities still occur.

UAS usage for illegal drug shipments or counter-surveillance supporting criminal activity

UAS usage has been increasingly linked to illegal drug shipments and counter-surveillance tactics supporting drug-dealing and other criminal activity. Criminal organizations and nefarious entrepreneurs have capitalized on drones’ ability to transport narcotics across borders or to monitor police activities during criminal activities. Smugglers utilize drones to bypass traditional border security or to surveil police movements, enabling them to evade detection and continue their illicit operations outside the presence of the police. Criminals have used drones to detect the presence or absence of police in the area where their activities are occurring.13

UAS usage for terrorism events, specifically threatening the public with munition payload deliveries

The utilization of UAS for terrorism events, particularly in threatening the public with munition payload deliveries, represents an alarming development. Terrorist organizations are known to adapt and exploit emerging technologies for their nefarious purposes. Weaponizing drones allow terrorists to target public spaces, infrastructure, or gatherings, magnifying the potential for casualties and infrastructural damage. One does not have to look far to witness this emerging tactic, as the war in Ukraine has revealed countless examples of using UAS to drop munition payloads on enemy positions. The use of drones by Houthis rebels and Iranian-backed terrorists have caused damage and casualties in the Middle East, including the recent deaths of three U.S. military personnel.14

Mitigating the UAS Threats: Detect, Classify, and Counter

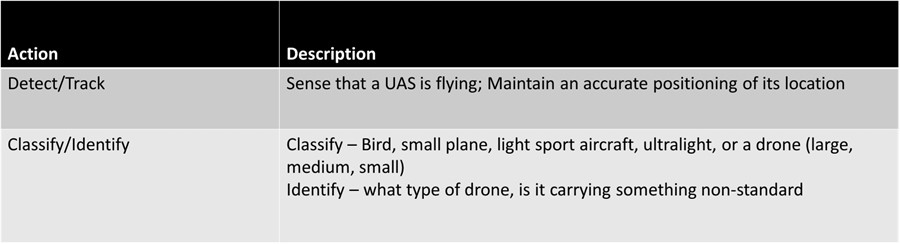

In order to address the threats caused by the use of UAS, a three-pronged preferred methodology of any UAS targeting package should be implemented: (1) detect, (2) classify (and identify), and (3) counter (interdict the pilot or mitigate the drone). Figure 4 provides a description of the first two stages of the targeting package methodology.

The first step is always detection, which is being able to determine that there is a UAS within an area of responsibility (AOR) and its location (tracking). This is followed by classification and identification of the specific type, model, and size of the UAS.

| Figure 4: First two stages of the Targeting Package methodology |

|---|

|

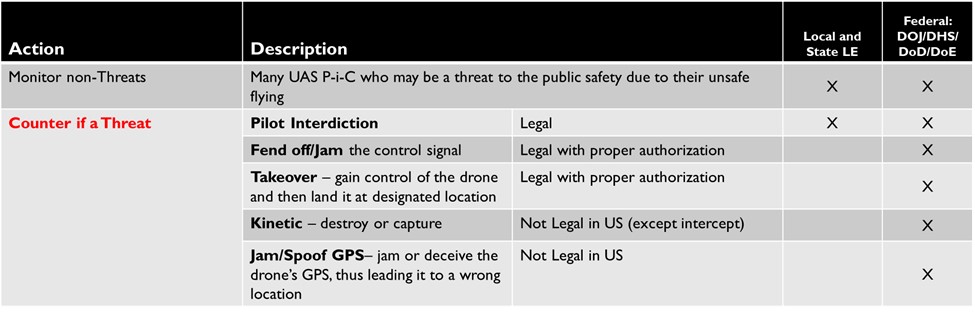

The third element of the methodology focuses on how to effectively deal with the threat (counter). There are several actions that can be taken to confront the UAS. Pilot interdictions have been used effectively by the police to cite or provide warnings to offending pilots-in-command. The use of cyber and kinetic countermeasures is currently limited by law to a few federal agencies only; however, there are models of partnership whereby local and federal law enforcement personnel work together to coordinate and implement appropriate countermeasures.

| Figure 5: The third stage of the Targeting Package methodology |

|---|

|

Situational Awareness of Low-Altitude Airspace Is Now Available

As stated previously, the only proven solution to confront the hazards posed by UAS to public safety is to install a wide-area, low-altitude aircraft monitoring system that provides cover over an entire city. This is achieved by stitching together multiple sensors at locations throughout a city and integrating those data into an intuitive and easy-to-use visual platform.

Until now, this equipment was prohibitively expensive for police implementation. Because of the FAA’s requirement that all UAS have Remote ID, U.S. police now have at least one tool at their disposal to gain some immediate situational awareness of the low-altitude airspace in their city or town—and some situational awareness is always better than no situational awareness.

Registration information of the UAS is now available to the police, giving them the ability to identify the registered owner of the UAS (at least those abiding by the law, which is still the vast majority of drone pilots). Additionally, when using a wide-area UAS monitoring system, police agencies can now also detect, track, classify, and identify drones in real time. This makes pilot positions available, enabling appropriate interdictions when necessary, which may include confronting; educating; and in some cases, citing individuals operating in a dangerous or unlawful manner.

Today, acquiring the equipment used to receive the Remote ID signals is now budgetarily manageable for many police agencies. Previously, to cover a city of 35 square miles with a basic system would require a minimum upfront investment and annual maintenance costs of $250,000 to $500,000. A tier-one Remote ID monitoring solution that includes sensors and monitoring software can now be implemented and maintained for less than a third of the prior cost.

Advanced Coverage with Additional Sensing Hardware

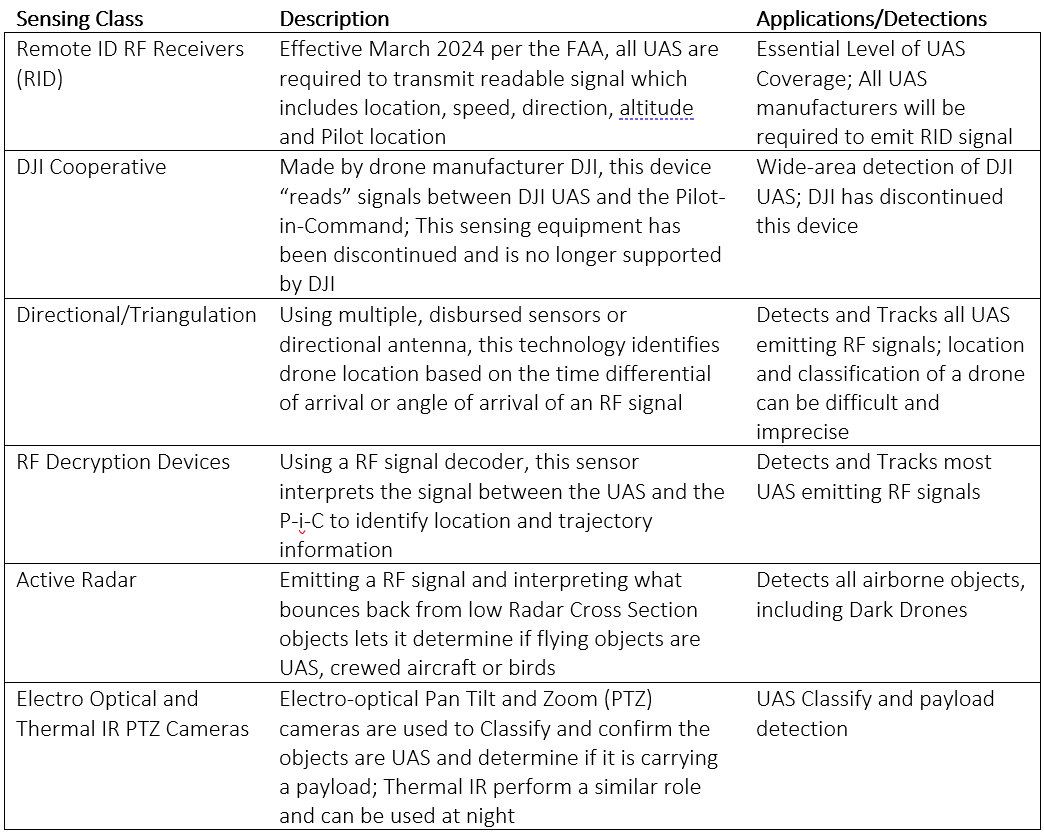

Moving beyond the relatively simple task of capturing Remote ID information requires installing and using more sophisticated sensors. But the physics of tracking, classifying, and countering a small UAS is extremely difficult. These small Radar Cross Section (RCS) objects moving over wide geographic areas are not uniform in size, radio frequency (RF) signature, and RF emission; and they can travel up to 100 knots at almost any altitude. Other human-caused and natural environmental considerations must be factored in as well. UAS detection relies upon line-of-sight to sense the RF signals. Varying terrain and buildings can interfere with this detection, as well as the presence of a “dirty” RF environment.

Because the challenge to “see” these small flying objects is so difficult, there is no single sensing device that can be relied upon as a complete solution. Today, there are many recently developed hardware solutions that now can contribute to the detect, classify, and counter equation. And to be most effective, each needs to be synthesized via an integration software into one common dataset that can be visually represented in a common operational picture (COP).

| Figure 6: Aircraft sensing hardware now available to police |

|---|

|

| Figure 7: An example of a Command and Control integrating software display |

|---|

|

Drone-sensing hardware has made considerable advances over the past few years and continues to react to and improve upon the changing UAS landscape. For the sake of simplicity, sensing hardware can be categorized into several UAS sensor classes.

| Figure 8: Sensing classes for UAS detection |

|---|

|

(SPS-ARS) |

The challenge of gaining situational awareness can be overcome by selecting the right type of equipment, and the correct quantity and location of equipment, given the parameters of a particular AOR. Questions to be posed include the following:

-

- What are the key locations within a city that need heightened protection?

-

- What geographic or terrain boundaries exist (human-made or natural)?

-

- Are there public venues that host large-scale events that may require a more robust and focused solution, whether short-term or long-term?

-

- How does the community feel about this new type of proactive policing method?

-

- What is the available budget for such a system?

Answers to these and other questions will dictate what layers of hardware make the most sense, and where they should be stationed or installed.

Integrating Command and Control Software

Having the right combination of hardware located in the right position is a prerequisite for eventually achieving appropriate situational awareness. But the glue that brings it all together is the integration of the various sensor outputs into a common dataset. This is achieved with an integrating command and control (C2) software package. The C2 must be flexible, with an open architecture that brings in and formats disparate data efficiently, and it must be able to be enhanced or adjusted as technology changes and improves. This C2 structure enables the police to see dynamically, in real time, any threat that arises in low altitude, so the potential threat can be mitigated through a pilot interdiction or, in extreme circumstances, defeated via partnering with a federal agency to employ more advanced countermeasures.

Figure 9: An advanced Command and Control software system, integrating multiple sensor data into a COP

The software can be programmed to produce visual and audible alerts based on parameters set by the agency, such as location, altitude, BVLOS violations. The reports can automatically push notifications to a command center or to select department personnel. The reporting package also offers police agencies with post-incident information for investigative purposes and, when analyzed appropriately, the ability to detect patterns of UAS flights that may be of interest, including consistent flight patterns at night or around protected areas

Figure 10: Sample reporting capabilities that are now available to the police to understand and address UAS threats

|

|---|

Conclusion

As the popularity and accessibility of UAS continue to rise, the risks they pose to public safety must be addressed by the police. Nuisance activities, malfunctioning drones, interference with public events, conflicts with crewed aircraft, delivery of contraband, drug shipments, and terrorism are significant threats that demand comprehensive solutions.

| Where to find more information about UAS – Detect, Classify, Counter: |

|

|

Remote ID regulations now provide police agencies with an affordable path to acquire sensors and software to detect and track drones and their pilots. This essential, basic coverage is the first step of implementing a multitiered system, and it could be deployed in cities to begin to level the playing field.

As perpetrators become more sophisticated, so will their UAS tactics. But emerging technologies are improving as well. By pairing multiple sensors with an integrating software, police agencies now have appropriate tools that can provide robust situational awareness of the airspace above their city to improve the safety of their community. The time to act is now. 🛡

|

The SPS Aerial Remote Sensing Team (SPS-ARS), headquartered in Texas, greatly contributed to this article. This team has successfully worked closely with local, state and federal law enforcement partners to achieve the first documented, city-wide coverage of a wide-area low altitude surveillance system over El Paso, Texas. |

Notes:

1Dan Gettinger, Public Safety Drones, 3rd ed. (Annandale on Hudson, NY: Center for the Study of the Drone at Bard College, 2020).

2Small Unmanned Aircraft Systems, 14 CFR 107 (2016).

3SPS Aerial Remote Sensing. Detailed information of these detection and monitoring systems can be made available from the author by request.

4Police Executive Research Forum, Drones: A Report on the Use of Drones by Public Safety Agencies—and a Wake-Up Call about the Threat of Malicious Drone Attacks (Washington, DC: Office of Community Oriented Policing Services, 2020).

5Federal Aviation Administration, “Remote Identification of Drones.”

6Alana Mitchelson, ‘“Peeping Tom Drones” Prompt Calls for a Close Look at Privacy Law,” The New Daily, April 27, 2017.

7Conner Forrest, Conner, “17 Drone Disasters That Show Why the FAA Hates Drones,” Tech Republic, June 13, 2018.

8Paul Duggan, “Drone Pilot Charged in Illegal Flyover at Baltimore Ravens Playoff Game,” Washington Post, February 6, 2024.

9Pamela Gregg, “Risk in the Sky: Impact Tests Prove Large Aircraft Won’t Always Win in Collision with Small Drones,” news release, University of Dayton Research Institute, September 13, 2018.

10The incident was recorded through the integrating software of SPS-ARS Systems, allowing for both Pilot-in-Command interdiction and post-incident evaluation and training by the FAA. Information on this incident and others is now available to other law enforcement agencies for review, by contacting SPS-ARS.

11U.S. Forest Service, Drone Incursion Interference with Wildfire Suppression Activities on Federal Lands Over the Past Five Years, 2021.

12National Institute of Justice, “Addressing Contraband in Prisons and Jails as the Threat of Drone Deliveries Grows,” June 2, 2023.

13Miriam McNabb, “The Changing Threat Landscape: How Criminal Use of Drones – and Counter Drone Technology – Is Evolving,” DroneLife, December 18, 2022.

14C. Todd Lopez, “3 U.S. Service Members Killed, Others Injured in Jordan Following Drone Attack,” DOD News, January 29, 2024.

Please cite as

David W. McGill, “The New Realities of Drone Proliferation: The Growing Threats and the Mitigation Solutions Available,” Police Chief Online, July 10, 2024.

Chief David McGill (ret) is the Director of Law Enforcement Solutions at SPS-Aerial Remote Sensing (SPS-ARS). He is a 32-year law enforcement veteran, serving with the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) for 25 years, and two other police departments in California and Arizona. David is also an instructor for the FBI-Law Enforcement Executive Development Association, and a contracted trainer for ICITAP (the International Criminal Investigative Training Assistance Program, operated through the US Department of Justice). He is currently the Chair of the IACP Retired Chiefs of Police Section, and he can be reached at

Chief David McGill (ret) is the Director of Law Enforcement Solutions at SPS-Aerial Remote Sensing (SPS-ARS). He is a 32-year law enforcement veteran, serving with the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) for 25 years, and two other police departments in California and Arizona. David is also an instructor for the FBI-Law Enforcement Executive Development Association, and a contracted trainer for ICITAP (the International Criminal Investigative Training Assistance Program, operated through the US Department of Justice). He is currently the Chair of the IACP Retired Chiefs of Police Section, and he can be reached at