“Unless the staff culture is transformed, then nothing has really changed.”

—Peter Perroncello, 20021

Culture is the collective set of values, beliefs, and traditions of a specific group. These values and beliefs can vary greatly from other cultures within an organization (e.g., shifts, districts, facilities within a law enforcement agency) and with different aspects of the community. This can create conflict both within the individual and the organization.

Changing the culture in a criminal justice organization takes active commitment and education. Many organizations evolve into competitive models, creating tension between sections, shifts, facilities, districts, and the community. A competitive organizational focus increases alienation and complicates the communication process. Barriers imposed by the organization or by one’s own self increase cultural conflict, resulting in organizations becoming dysfunctional toward staff and those they protect and serve.2

Higher education is often seen as a means of improving officers and criminal justice organizations.3 Studies support the conclusion that a college degree reduces the level of bias and prejudice in both law enforcement and corrections personnel.4 However, while education has helped in the improvement of officers, it has had limited impact on criminal justice organizations. This article discusses some of the factors that could result in cultural conflict, attempts to improve the situation through education, and reasons why it hasn’t always resulted in the anticipated changes.

Potential Areas of Cultural Conflict

Philosophy of Punishment

Different philosophies toward punishment coexist in the criminal justice system. These philosophies, which drive the behavior of criminal justice professionals, are often in conflict with each other and society. How a society decides to punish offenders may vary depending on its culture. Many views of punishment can exist in a single culture, such as the following, for example:

• “Eye for an Eye”—equal retribution for a wrong.

• “Just Desserts”—appropriate punishment to occur sometime in the future. This can include the offender’s being assaulted or killed while in jail or prison.

• “Lock the door and throw away the key”—a conservative view that sees the need to be “tough on crime.”

• “Rehab for everyone”—a liberal view that wants to reform the system to better address the needs of the offender and society.

• “The offender is also a victim”—a point of view that considers the offender as a product of a bad environment.

• “The officer is the punishment”—a view that the encounter with the system is an appropriate consequence; however, the U.S. Supreme Court has ruled the “separation from society” is the punishment, not the officer or the system.5

All of these beliefs currently exist in the criminal justice system and are often in conflict with each other. The philosophy with which the individual or organization mainly identifies can influence the approach to a situation. Although most officers try to provide a firm but fair approach, this practice could conflict with the “lock the door and throw away the key” and “the officer is the punishment” philosophies potentially held by other officers, administration, public officials, and the community.

An organization might collectively believe in one philosophy, while an officer employed there might be more inclined toward another philosophy. These philosophies of punishment have an impact on the behavior of the officers, supervisors, and those with whom they interact within the community. A disconnect in philosophies, then, creates possible conflict within the culture of an organization and society.

Individual versus Offender

Criminal justice personnel have been taught to consider the individual as an inmate, suspect, or offender. This perspective drives a shift of their mind-set to neutral. (This is also as an officer safety measure consideration.) However, instead of neutral, it presents its own beliefs and assumptions about those involved in crimes. Failing to reach a neutral mind-set is seen as a form of institutional prejudice toward criminals.6

Example: “Sarge, you don’t understand, this a black and white issue.”

Response: “You don’t understand, this is an orange issue.”

In this exchange, both groups are looking at the same issue from different viewpoints.

In spite of efforts by higher education to improve the beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors within the criminal justice system, cultural conflict still exists in law enforcement and corrections. While higher education has improved law enforcement, corrections officers, and organizations in general, in some instances it has had a limited impact on improving behaviors.

Education

Education (both in-service education and higher education) has been seen as essential in the efforts to improve both the individual and society. While most would argue the goals and approaches should be different for these efforts, some believe the improvement of the individual will also result in the improvement of society. Education has been viewed as a means of challenging old ideas, beliefs, and values, thus allowing new ideas, beliefs, and values to be instituted into the culture of an organization. Individuals need to be encouraged to learn new concepts, techniques, and procedures and to gain empowerment.7

Education has also been seen as the means to improve the officer and the criminal justice organization. While studies have shown improvement of the officer, education has had limited impact on the organization. The educated new officer is introduced to the old adages—“This is the way we have always done it” or “This is the traditional method of doing things”—and the “officer is the punishment” philosophy.8 However, as society has changed, the drive to improve the criminal justice organization has increased. The organization must learn to change with society in order to succeed.9

1967 President’s Commission Report

While efforts were being made to improve the criminal justice system, society saw little change in criminal justice organizations. The civil rights disturbances in United States in the 1950s and 1960s led to the creation of the President’s Commission on Law Enforcement and Administration of Justice, which released a report in 1967. The commission recommended that all officers possess a four-year degree, stating that “Studies support the proposition that well-educated persons are less prejudiced toward minority groups than the poorly educated.” The commission also suggested that a degree “should have a significant positive long-term effect on community relations.”10

According to the commission, police personnel with two to four years of college should have the following characteristics:

• A better appreciation of people with different racial, economic, and cultural backgrounds

• An innate ability to acquire such understanding

• Less bias, prejudice, and use of excessive force11

The commission believed a degree would result in better officers. However, higher education was still seen as an individual effort, not an organizational mandate. Unfortunately, the commission did not suggest any specific courses toward resolving cultural conflict.

Individual Responsibility

The development of basic and advanced education has taken several directions since the 1960s. While many law enforcement agencies have focused on basic academy and in-service education, most agencies have left the responsibility for higher education to the individual officers. Community colleges and universities have developed curricula in law enforcement administration and other criminal justice areas.12 Officers have primarily attended in-service and college education for personal development, for promotion, for learning how to resolve specific situations, and for increasing involvement in community service.13

The need for specific education, the amount of education, and the quality of education are influenced by the location of the law enforcement agency (rural versus urban), size of the agency (large versus small), and the number of officers who need additional education.14 While this may vary by organization, in-service education should address the beliefs and attitudes toward the philosophies of punishment and cultural beliefs within the organization and toward society. Police officers are aware of the education needed to effectively do their job. The information on cultural conflict should be “application driven,” with officers allowed to use the education provided in the classes in the field. The information needs to address specific issues and concerns to improve the situation.15

College-educated officers overall have fewer complaints against them about excessive use of force, experience fewer disciplinary actions, and commit other infractions less often. They are seen as having increased flexibility in dealing with difficult situations, better interactions with people from diverse cultures, better verbal and written communication skills, and greater flexibility in accepting and implementing change.16

However, since not all officers have attended college, the impact of higher education on criminal justice organizations is limited.

Limited Impact in the Pursuit for Justice

The intent of the 1967 President’s Commission was to change the system—not to necessarily control crime, but rather to create justice.17 The intent of having academia to help create this change was never fully realized, but research on the effects of education did increase. Academia did increase the skills of the officer, but it did not provide the information and stimulus needed to change the system.

Community college and university criminal justice curricula were seen as being in conflict with the criminal justice system. After the 1967 President’s Commission report suggested a four-year degree, colleges and universities combined several existing courses together with a few courses on criminal justice. Criminal justice was viewed as a social science, not necessarily as a tool for resolving issues and conflicts in the streets. A need still existed to create an educational program that raised awareness and enhanced critical thinking to better deal with situations on the streets.18

There are three major concepts in the professionalism of criminal justice:

1. Technically competent people

2. People committed to the right values

3. People who feel authorized to imagine and act

This multipronged view has resulted in better leadership and greater professionalism in criminal justice.19

Organizational and Community Justice

Officers and the community should have a sense of organizational justice. The community and the officers should feel the criminal justice organization provides fairness in its interactions. Organizational justice is viewed as a philosophical approach to provide the following:

• Procedural fairness—a reasonable voice in the decision-making process

• Distributive fairness—equal distribution of promotions, salary increases, and opportunities

• Interactional fairness—respect, dignity, and open and honest relationship with others

• Community fairness—transparency, trust, dignity, and reduction of the dependence on force to gain compliance (a voice which will be heard and acted upon)20

The officers, organizations, and the community should strive to obtain organizational justice and fairness by working together.

Basic Academy as a Filter

A study done in Queensland, Australia, illustrated the differences between two models of using college education in criminal justice. Both models were designed to use education to resolve major issues in the criminal justice system. The first model required all police recruits to attend two semesters at a local college prior to attending the police academy; the second model was college attendance after the academy. The study showed that if a police recruit had positive beliefs on specific issues, those beliefs would often erode during the academy and would then further erode during field training sessions.21

The academy and field training sessions were often taught by current officers in the organization. The instructors introduced the recruits to the organization’s existing culture, therefore limiting the impact of the college education. The college degree, by itself, did not guarantee better officer performance or a change in the organization.22 While a college education was shown to benefit the officer, organizational benefits were not as easily identified.23

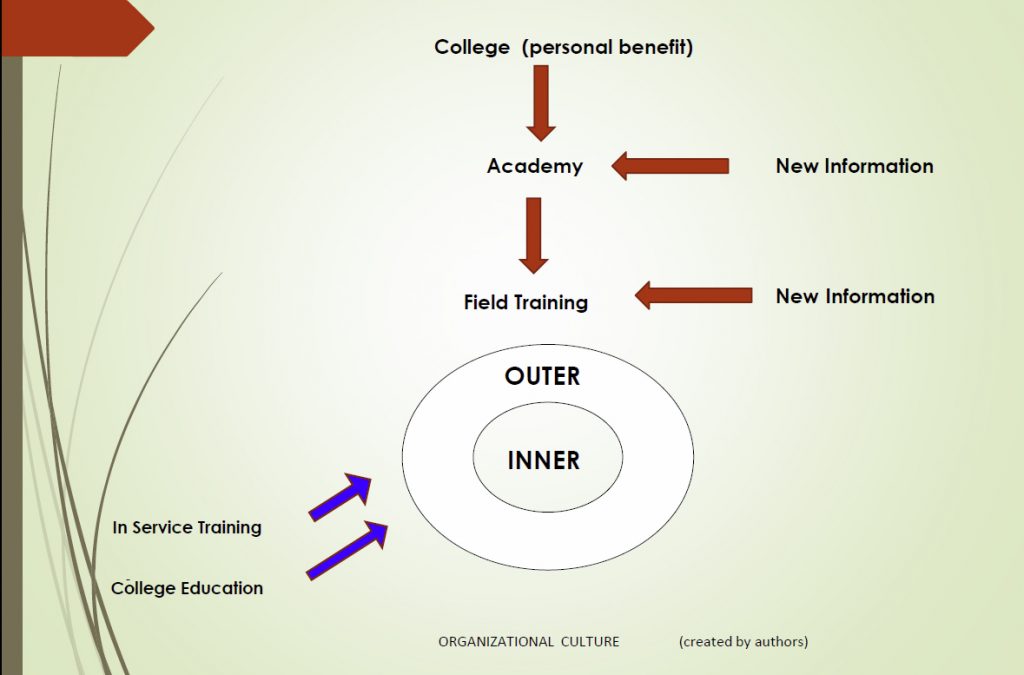

Figure 1 shows an organizational culture as having an inner and outer core. The inner core is defensive (not wanting to change), even if it is dysfunctional. Information obtained during the basic academy, field training, in-service training and college might result in changes in the outer core, but to have an impact on the inner core, education and commitment to change have to exist at all levels of the organization.

Cultural Conflict Curriculum

Many in the criminal justice and higher education professions have recognized the need to better educate officers and improve the criminal justice organizations. There is debate on which topics should be presented to the officers (firearms training, first aid, driving skills, report writing, and so forth). The 1967 President’s Commission felt a four-year degree would result in “lower bias, prejudice, and excessive use of force.”24

A study was conducted on the issues upon which officers felt higher education should focus.25 The study noted that, while officers and students thought race and ethnic relations should be a focus of a graduate curriculum, a review of race and ethnic relations was found in less than three-fourths of introductory textbooks. Most criminal justice textbooks provided one chapter on the topic.

Cultural Conflict in Criminal Justice Curriculum Studies

A survey was conducted with 926 U.S. college criminal justice professors (members of the Academy of Criminal Justice Sciences) on the philosophy of punishment and cultural conflict courses. Seven professors completed the survey. When the criminal justice professors were asked if one class on cultural diversity was sufficient to change the beliefs and behaviors in criminal justice, all responded that it was not. A few commented that “one course on cultural diversity is not enough to change an organization” and that “while courses on cultural diversity are provided to current and future officers, it is not provided to the community.”26

A review of the 30 U.S. colleges and universities’ criminal justice programs represented by the survey respondents determined the number of cultural diversity, conflict, ethics, and decision-making courses being provided, with the following results:

• At least one or two courses that covered issues of cultural diversity, ethics, and decision-making were offered in most colleges and universities.

• Some colleges and universities are including more classes to address these issues. For example, Eastern Kentucky University has developed an entire degree program to focus on social justice.

• Some programs take an integrative approach by having one identified course, while also addressing diversity across the curriculum to further facilitate cultural diversity.

• Some progress was being made in the colleges and universities, but more work remains to be done.

• Instructors were discussing the issues more in the classroom. This trend is more of an individual effort than institutional effort.

Limitations

Due to the low response rate to the survey, it would be difficult to provide a pattern for comparison. Information obtained provided a limited view, but it was consistent with informal surveys during presentations. While the colleges and universities did provide courses on cultural diversity, reviews of the course description were not performed. Research needs to focus on the effectiveness of the offered cultural diversity courses and its impact on the students and organizations.

Questions that need to be addressed in further research on the topics include:

• Could these cultural diversity courses be provided in a forum so as to improve relations between criminal justice professionals and the community?

• What other courses could be developed to improve the criminal justice organizations?

• Should elements of these courses in cultural diversity be provided in other courses to result in a more comprehensive approach?

For higher education to fulfill its role in improving the criminal justice system, more research is needed to better address the philosophy and beliefs of the officers, organizations, and society.

Conclusion

The philosophy of punishment is a part of the criminal justice culture and society. Many people have strong views on punishment, which influence the behaviors and decision of criminal administrators, politicians, and officers. Since the early 20th century, basic education of criminal justice personnel has primarily focused on developing the skills necessary to be effective in the field. While the 1967 President’s Commission saw the need for the a four-year degree, there was no emphasis on addressing the issues of “bias, prejudice, and excessive use of force” in coursework.27

Over the years, most academic institutions have established at least one class on cultural diversity at each degree level (associate, bachelor, masters, doctorate). However, when criminal justice professors were asked if one class was sufficient to change the criminal justice culture, all said “no.” While higher education has made an effort to address specific issues impacting criminal justice and society, it could still do better.

Somehow, we’ve gotten the idea that we are different, and we have put up an imaginary boundary based on the demographics of the world…we put up all these imaginary lines and the world is not like that…All they (barriers) keep us from doing is what we really need to do to be productive.28

Cultural conflict between the criminal justice organization and the community has existed for many years. While some police and sheriff’s departments have made progress, others are still struggling. Higher education, departments, law enforcement agencies, and the community have to work together to achieve fairness and justice.♦

Notes:

1 Peter Perroncello, “Direct Supervision: A 2001 Odyssey,” American Jails (February 2002): 25–31.

2 John Shuford, “The New Generation Staff Development Training for Jails,” American Jails 18, no. 3 (July/August 2004): 69–70.

3 Richard P. Seiter, Corrections: An Introduction, 3rd Ed. (Boston, MA: Pearson Education, 2011), 397–399.

4 Cody W. Telep, “The Impact of Higher Education on Police Officer Attitudes Toward Abuse of Authority,” Journal of Criminal Justice Education 22, no. 3 (September 2011): 392–419.

5 Raymond M. Delaney et al., “Impact of Higher Education on Cultural Conflict in Criminal Justice,” Southern Arizona Intercollegiate Journal 4, no. 1 (Fall 2015): 19–23.

6 Barbara Armacost, “The Organizational Reasons Police Departments Don’t Change,” Harvard Business Review, August 19, 2016.

7 Peter G. Northouse, Leadership: Theory and Practice, 2nd ed. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2001).

8Delaney et al., “Impact of Higher Education on Cultural Conflict in Criminal Justice.”

9 Jocelyn A. Butler, Staff Development, School Improvement Research Series VI, 12 (Education Northwest, 1992); Peter Perroncello, “Direct Supervision”; Michael Fullan, Leading in a Culture of Change (San Francisco, CA: Josey-Bass Publishers, 2004).

10 Robert Wallace Winslow, Crime in a Free Society: Selections from the President’s Commission on Law Enforcement and Administration of Justice (Berkley, CA: Dickenson Publishing Company, 1968), 278.

11 Winslow, Crime in a Free Society.

12 James W. Stevens, “Basic and Advanced Training of Police Officers: A Comparison of West Germany and the United States,” Police Studies 6, no. 3 (Fall 1983): 24–35.

13 D. Johnson, “A Study of Law Enforcement Officers’ Participation in Continuing Education” (PhD diss., Kansas State University, 1986), ProQuest (8624657).

14 W. Miller, “An Analysis of Perceived Training Needs of Rural County Sheriff’s Departments (Oklahoma)” (PhD diss., University of Oklahoma, 1994), ProQuest (9422544).

15 T. Mors, “Critical Issues Impeding Criminal Justice Continuing Professional Education,” abstract (PhD diss., Northern Illinois University, 2002).

16 M. Totzke, “The Influence of Education on the Professionalization of Policing” (capstone project, University of Nebraska, 2002); Charles Wymer, “A Comparison of the Relationships between Level of Education, Job Performance and Beliefs on Professionalism within the Virginia State Police” (PhD diss., Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, 1996), ProQuest (9624257).

17 Dominick R. Varricchio, “Higher Education in Law Enforcement and Perceptions of Career Success” (EdD diss., Seton Hall University,1999).

18 Michael Buerger, “Educating and Training the Future Police Officer,” FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin 73, no.1 (January 2004): 26–32.

19 Mark Moore, “Looking Backward to Look Forward: The 1967 Crime Commission Report in Retrospect,” National Institute of Justice Journal (December 1997): 24–30.

20 Scott Wolfe and Justin Nix, “Managing Police Departments Post-Ferguson,” Harvard Business Review, September 13, 2016.

21 Kerry Wimshurst and Janet Ransley, “Police Education and the University Sector: Contrasting Models from the Australian Experience,” Journal of Criminal Justice Education 18, no. 1 (2007): 106–122.

22 Robert E. Worden, “A Badge and a Baccalaureate: Policies, Hypotheses, and Further Evidence,” abstract, Justice Quarterly 7, no. 3 (1990): 565–592.

23 Wimshurst and Ransley, “Police Education and the University Sector.”

24 Winslow, Crime in a Free Society.

25 Charles J. Corley, Mahesh K. Nalla, and Vincent J. Hoffman, “Components of an Appropriate Graduate-Level Corrections Curriculum,” Criminal Justice Studies 18, no. 4 (2005): 379–392.

26 Ray Bynum et al., “Philosophy of Punishment, Education and Cultural Conflict in Criminal Justice,” (presentation, American Association of Behavior and Social Sciences Conference, Las Vegas, NV, January 30, 2017).

27 Winslow, Crime in a Free Society.

28 Laura L. Bierema and David M. Berdish, “Creating a Learning Organization: A Case Study of Outcomes and Lessons Learned,” Research Review, Performance Improvement 38, no. 4 (April 1999): 36–41.