In October 2006, “Police Officer Recruitment: A Public Sector Crisis,” was published in Police Chief. The article identified a number of issues impacting the recruitment of police officers including an anticipated increase in the number of vacant positions directly related to baby boomers preparing to retire and the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan syphoning off potential recruits. Also addressed were different approaches used for recruitment purposes, changing qualification standards recognizing greater exposure and experience with the use of marijuana, and creative incentives offered to attract candidates.

A decade has passed. What has changed? Does it continue to be difficult to fill law enforcement officer positions? Are public jurisdictions doing anything different to attract candidates? Are there new issues not contemplated 10 years ago that now affect law enforcement that must be addressed with respect to the recruitment of police officers? Is there a public-sector crisis, the question left open from the title of the article 10 years ago?

Many of the issues identified in the 2006 publication have subsequently been addressed in journals and other publications.1 During the past decade there have been a number of issues, some not necessarily anticipated, impacting law enforcement that may have affected recruitment for sworn positions. A review of some of the more significant issues are identified herein.

An Overview of the Past Decade

The Impact of High Technology

Facebook, Twitter, Salesforce, Square, Groupon, Dropbox, and Zynga are just a few of the many companies established in the last decade. These companies have a combined workforce exceeding 100,000 employees. The “job drain” caused by these and other high-tech companies continues to be an issue with respect to law enforcement officer recruitment.

Many technology companies provide salary and benefit packages that far exceed what is offered to law enforcement officers. Supplemental benefits for tech employees might include not only the basics provided to public sector employees, but also on-site services, including meals, cleaning services, childcare, health care, and a workplace environment that would be the envy of any public-sector employee. As an example, the following is a brief outline of benefits offered to employees working for Google (“Googlers”) that cannot be found in the public sector:2

- Free gourmet food and snacks.

- Googlers are free to bring their pets to work.

- Googlers living in San Francisco, California, have free transportation to and from the main campus in Mountain View, California (78 miles round trip).

- Free one-hour massage on campus for jobs well done.

- Free fitness classes and gyms on campus.

- On-campus health, wellness, childcare, and cleaning services.

- An “80/20” rule allows Googlers to dedicate 80 percent of time to their primary job and 20 percent working on passion projects that they believe will help the company.

- On a continuing basis, presentations and lectures that are open to employees to either attend or watch remotely.

The companies identified previously are just a few of the many new high-tech companies during the last decade. There is little question that high-tech employment opportunities are attractive to many men and women, some of whom, at an earlier time, may have been interested in a law enforcement career.3

Negative Publicity

The media continues to have a serious impact on recruitment with never-ending reports of police officer incidents, many portrayed in a negative manner. The 2012 shooting death of Travon Martin in Miami Gardens, Florida, by George Zimmerman, a civilian member of the neighborhood watch, and his subsequent acquittal of charges of second degree murder and manslaughter, resulted in the activist movement Black Lives Matter (BLM). BLM regularly organizes protests around the deaths of black people in officer-involved shootings and broader issues of racial profiling and racial inequality in the criminal justice system.

The shooting deaths of Michael Brown, Eric Garner, Tamir Rice, and Laquan McDonald, have saturated national news coverage in the last several years. Journalists have a duty to report the news and the deaths of these individuals. However, there is a question as to whether the headlines reporting the incidents are balanced. For example, the headline reporting an incident in Las Vegas, Nevada, read “Suspect Fatally Shot by Cops Had Phone, Not Gun.” 4 While a true statement, the headline does not explain to readers that the victim had been convicted of burglary, armed robbery, kidnapping, aggravated assault, and theft or that the Las Vegas police were assisting U.S. marshals in arresting the individual because he was accused of multiple violent felonies in Arizona including attempted murder, was fleeing from federal authorities, and refused to drop the object he was holding. The increasing use of body-worn cameras by law enforcement officers has gained wide acceptance in multiple countries following reports of shootings by sworn officers. In the United States, in particular, body-worn cameras have become a method of defending officers in situations where protests and other incidents occur, some of which are generated by headlines in the press designed to attract attention. The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) recently released a video taken from an FBI airplane of a protester’s shooting death in Oregon. The special agent in charge of the FBI field office in Portland issued the following statement: “We realize that viewing that piece of the video will be upsetting to some people, but we feel that it is necessary to show the whole thing unedited in the interest of transparency.” The FBI released the video to allay public concerns caused by “inflammatory” accounts of the shooting.5

The question as to balance relates to the headline. An individual reading only the bold caption may conclude without reading the story that the incident was just another example of cops out of control. This type of unmitigated negative media might dissuade a young person who is considering a law enforcement career.

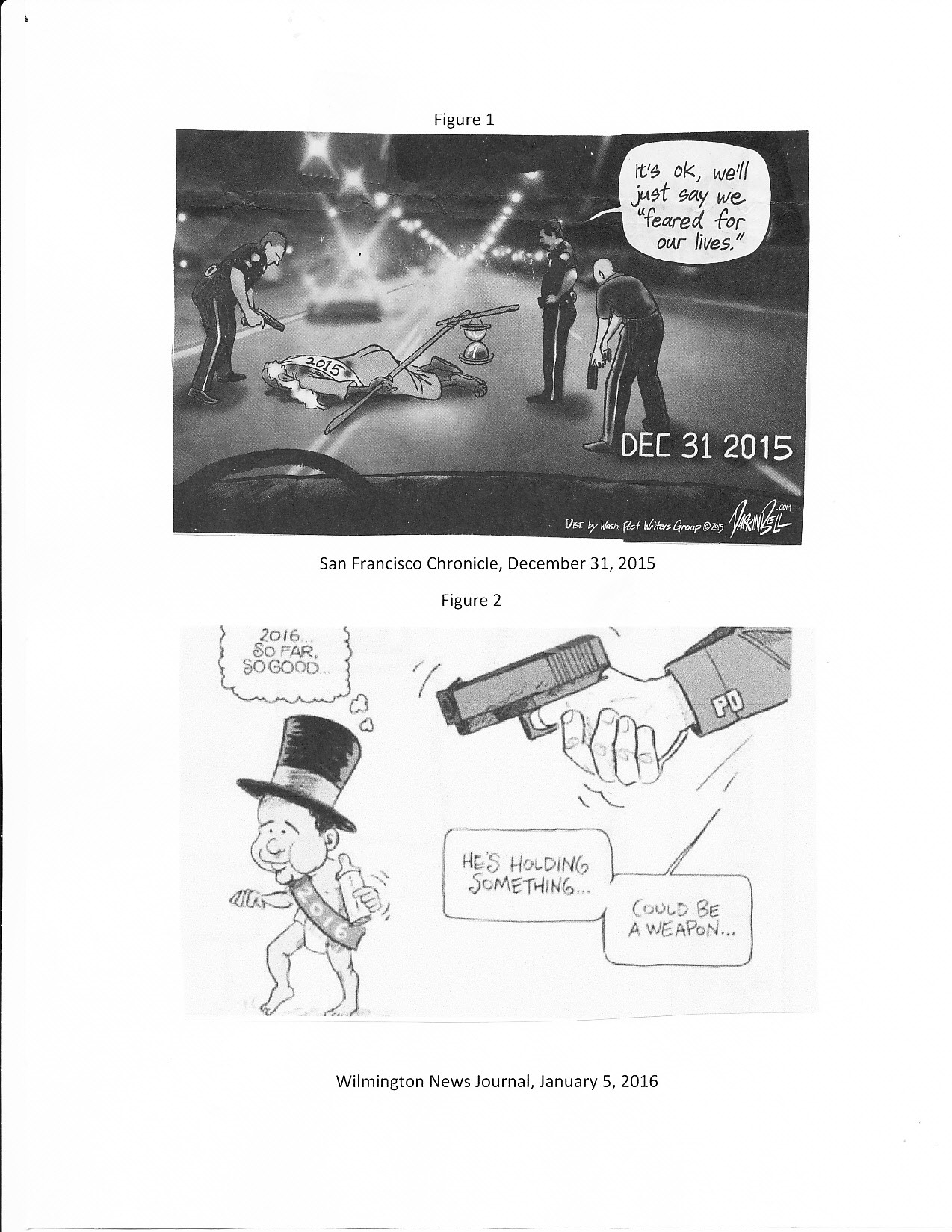

Another common form of media commentary—editorial cartoons—can be as harmful to the recruitment of law enforcement officers as a negative headline. Figures 1 and 2 are examples of political cartoons portraying law enforcement activities in unfavorable lights.

An individual interested in becoming a law enforcement officer may consider otherwise when friends and other close associates make fun of the negativity of the cartoons toward law enforcement officers.

Finally, the last edition of USA Today for 2015, in a story under a headline referencing newsworthy issues, a statement in bold print summarizes the columnist’s research and succinctly makes the point: “Bad news draws your attention even as many of you say you wish our profession (journalists) would champion more good news.”6

Officer-involved shootings draw the attention of journalists, and the resulting headline draws the attention of readers. It is imperative that newspaper headlines be straightforward and fair with respect to both the reader and the law enforcement profession if young adults are to be expected to sincerely consider law enforcement a viable career option.

The Ferguson Effect

The shooting of Michael Brown, an unarmed African American teenager, on August 9, 2014, in Ferguson, Missouri, by a white police officer, ignited existing tensions in a predominantly black city and led to protests and civil unrest in communities across the United States. The disputed circumstances of the shooting generated a debate about the relationship between law enforcement and the black community. The incident has led to what many call “the Ferguson effect.”

The Ferguson effect is based on the theory that recent increases in violent crime can be ascribed to negative publicity associated with law enforcement actions, such as the shooting of Michael Brown and the subsequent riots.7 Additionally, the theory suggests that the spike in violent crime is caused by law enforcement officers shying away from aggressive police work because they are worried that their actions will be caught on film and that they will be targeted by civil rights lawyers and anti-police activists, regardless of whether the officers’ actions are legitimate or not.8 The ongoing criticism of law enforcement in general and, more specifically, of the officer on the street is that a wrong move in an arrest or a use-of-force incident could be a career breaker.

A recent example of a perilous situation caught on video was in Fremont, California, where a cellphone video captured an individual being held at gunpoint by an officer outside of a stolen truck. The suspect then returned to the vehicle, reached inside, and quickly fired a burst of rounds, critically wounding the officer. About 10 minutes later, the suspect shot a second officer while fleeing on foot. A San Francisco Bay area attorney who represents law enforcement officers commented,

If they wait as a person walks to the car to see what they’re doing, there’s a high possibility they could get shot. If they act preemptively, and shoot as the person moves back to the car, there’s a possibility the person was not reaching for a weapon and then they become front-page news.9

This statement illustrates the dilemma that officers face during a time of heavy scrutiny of police shootings:

What’s missing from the current dialogue [on police actions] is an understanding of why police officers shoot when people take particular behaviors. This is an illustration of that—a person going back to their vehicle after being told to put their hands up.10

With respect to the Ferguson effect and its impact on morale, the head of the International Institute of Criminal Justice at the University of San Francisco pointed out that “There is no question right now that a lot of officers all around the country feel they are being persecuted.”11

In a 2015 study co-authored by professors at the University of South Carolina and the University of Louisville published by the American Psychological Association involving 567 deputies at a mid-sized sheriff’s department, it was found that “ there appears to be a relationship between reduced motivation as a result of negative publicity and less willingness to work directly with community members to solve problems.” However, the study also found that if the participants’ perception of departmental fairness and confidence in their authority as police officers were taken into account, there is no impact of the so-called Ferguson effect. The authors imply that the reduced motivation attributable to negative publicity may be counteracted if supervisors ensure fairness among subordinates.

Little actions can go a long way. Fair treatment from supervisors sends the message to officers that ‘we are here for you’ regardless of how much the public or media try to sully law enforcement.12

The Recession

The economic recession beginning in 2008 has had a significant impact on public sector budgets and services. But for the recession, cities such as Vallejo, Stockton, and San Bernardino, California, might not have had to file for bankruptcy. There have been other municipalities throughout the United States, including Detroit, Michigan, with a population exceeding 700,000, that filed for bankruptcy since the beginning of the recession.

The recession affected law enforcement agencies throughout the United States. The International Association of Chiefs of Police (IACP) estimated that, in 2011, there were 10,000 fewer law enforcement officer positions than in 2008.13 San Jose, California, the 10th-largest city in the United States, with more than 1,400 officers prior to the recession, “will shrink to two-thirds its size in 2008” by June 2016, according to police department projections.14

Although it may be difficult to measure the continuing impact of the economic downturn on law enforcement agencies as the economy improves, there is no dispute that there are fewer sworn positions. The U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) periodically conducts surveys of law enforcement agencies. A BJS Law Enforcement Management and Administrative Statistics (LEMAS) survey reported that. from 2004 to 2008. the average ratio of officers to members of the public was about 250 per 100,000. By 2011, that average had dropped to 181 officers per 100,000.15

While budget cuts have eliminated the jobs of some sworn officers, the profession’s responsibility for providing public safety continues. Some law enforcement agencies began to shift some of the duties typically performed by sworn staff to civilian employees as a means of saving costs or managing the workload with fewer officers. A survey by the IACP reports that 22 percent of the respondents stated that their departments had begun shifting sworn responsibilities to non-sworn personnel.16 In the Twin Cities of Minneapolis and Saint Paul, Minnesota, the Police Authority and the San Anselmo Police Department began taking steps towards consolidation by sharing some dispatch services and officers.17 Other agencies have managed shrinking staff by no longer responding to burglar alarms or non-injury accidents.18

The significance of the recession to officer recruitment relates to the eventual need to fill new (or reinstated) sworn positions as the economy improves. Many veteran officers who lost their jobs will not return because of other opportunities or retirement. In addition to the difficulty in filling vacant positions not impacted by the recession, the additional vacancies created by laid-off employees who are not returning can exacerbate the never-ending frustration of recruiting police officers.

Reduction in Law Enforcement Retirement Benefits

Nearly all public-sector pension systems are defined benefit (DB) plans. DB plans are employer-sponsored retirement plans in which workers are promised a fixed pension after retirement in the form of an annuity. The benefit is typically linked to the participant’s age, final salary, and the number of years of service, with the exact formula varying by employer. The vast majority of law enforcement officers are covered by DB plans.

DB pension plans were generally 100 percent funded between 1974 and the late 1990s. During a five-year period beginning around 1997, public-sector DB pension plans were more than 100 percent funded. However, a perilous drop in funding occurred with the 2008 recession, and there has been little, if any, recovery. It is estimated that DB pension plans were underfunded by $1.3 trillion dollars in the second quarter of 2014.19

Public agencies throughout the United States are beginning to realize that, because of the continuing increase in the unfunded liability of pension plans, changes must occur. With increased pension costs combined with the need to balance a budget, the cost of retiree benefits is crowding out other governmental services, including public safety. “Crowd out” has become a feature of DB benefit systems. Reductions in staffing at all levels—including police, fire, and other public safety positions—are occurring because of the need to balance budgets in light of increasing pension costs.20

Across the United States, state government and other public agencies are introducing pension reforms in an attempt to address unfunded liability issues. These reforms include a combination of increased pension contributions by employees, reductions in pension contributions by employers, reductions in benefits, increases in age and service requirements, and adjustments in the calculation of final salary for retirement purposes.21

For example, the state legislature in California approved the Public Employee Pension Reform Act of 2013 (PEPRA), which was subsequently signed into law by Governor Jerry Brown. PEPRA affects all new employees hired after January 1, 2013, that are covered by California’s Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS), the United States’ largest public pension fund, with a market value approaching $300 billion dollars in 2013.

In addition to the State of California, more than 700 public agencies in California contract with CalPERS for retirement benefits. Almost all cities in California are covered. Figure 3 provides a limited overview of the difference in retirement benefits for sworn law enforcement personnel between the pension system in effect prior to and after January 1, 2013.

Figure 3: Retirement Benefit Comparison |

||

| Before 2013 | 2013 and After | |

| Benefit formula | 3% @ age 50 | 2 to 2.7% @ age 57 |

| Final compensation | Highest 12 months | Highest average 36 months of pensionable compensation |

| Pensionable compensation | Additions to base pay | Normal monthly rate (base pay) |

| Maximum compensation | Not limited | IRS limitations |

| Employee contribution | Less than 50% of DB cost | At least 50% of DB cost rate |

Retirement benefits provided for public safety employees are a significant incentive for positions exposed to life-threatening situations on a regular basis. Prior to California’s 2013 PEPRA legislation, a sworn California law enforcement officer hired at age 21 could retire at age 50 with 29 years of service and an 87 percent benefit with cost of living adjustments (COLAs). However, an individual of the same age and qualifications hired after 2013 would receive a benefit of 58 percent with COLAs. The difference in the pension benefit might prove detrimental to law enforcement recruitment.

Pension reforms have a direct impact on attracting individuals to the law enforcement profession. Jim Preston, president of the Florida Fraternal Order of Police, reports that pensions are one of the key benefits job-seekers consider and that cities that offer the best retirement benefits attract the best candidates.22 The significant difference in the pension benefit resulting from the PEPRA legislation in the State of California between sworn personnel hired before and after 2013 will be closely followed with respect to the impact on hundreds of public-sector employers and their attempt to recruit law enforcement officers

Conclusion

In the first six months of 2016, there was a 78 percent increase in the shooting deaths of law enforcement officers compared to the first six months of 2015. Ambush-style killings occurred in Dallas, Texas, where five officers were killed and in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, where three officers were killed.23 The headline deaths of individuals who have sworn to uphold and enforce the laws of communities throughout the United States, in addition to the negativity of news concerning the law enforcement profession, continue to have a detrimental impact on the recruitment of officers.

It is apparent that the last decade has had an unfavorable impact on the capability of law enforcement agencies fulfilling their role in providing public safety services considering reductions in staffing and services caused by the 2008 recession. The increase in U.S. media coverage of law enforcement actions resulting from single events recorded by security systems and cellphone videos has increased negative perceptions of the profession and officers. Law enforcement agencies find themselves increasingly requiring officers to wear body-worn cameras to assist in avoiding misinformation about law enforcement incidents. Is there a public-sector crisis in recruiting law enforcement officers? The most recent findings of the U.S. Department of Justice are of assistance in answering the question left open 10 years ago.24

- A majority of agencies in all size categories were willing to consider applicants with a misdemeanor conviction, including more than 80 percent of agencies employing 100 or more officers.

- Nearly half (47 percent) of agencies allowed the hiring of applicants with prior marijuana use, including more than 80 percent of agencies with 100 or more officers. Overall, a sixth of agencies considered hiring applicants who had used illegal drugs other than marijuana, including more than half of agencies with 100 or more officers.

- About 4 in 10 agencies were willing to consider applicants with prior driving-related problems such as a suspended license or a conviction for driving under the influence. Nearly 9 in 10 agencies with 100 or more officers had such a policy.

- In 2008, more than two-thirds of officers worked for agencies that allowed the consideration of highly qualified applicants whose personal history included prior credit related problems (82 percent), marijuana use (76 percent), a misdemeanor conviction (75 percent), a suspended driver’s license (72 percent), or job-related problems (71 percent).

There is no question that the qualification standards to become a law enforcement officer have changed. For example, residency requirements have been relaxed in an effort to expand the applicant pool.25 Among agencies with 500 or more officers, 80 percent have a full-time recruitment manager.26 Job fairs, special events, agency and employment websites, radio and television advertisements, and other sources are continuously being used for recruitment purposes. Recruitment incentives, including college tuition, flexible hours to attend college, signing bonuses, and relocation assistance, are being offered by many jurisdictions, and some agencies even offer a training academy graduation bonus to attract candidates.27

Negative publicity, low morale, reduced retirement benefits, scaled-down qualification standards, relaxed residency requirements, enhanced recruitment procedures… the question remains: Police Officer Recruitment: A Public Sector Crisis?

William J. Woska has been a faculty member at several colleges and universities including the University of California, Berkeley; Saint Mary’s College, Moraga; Golden Gate University, San Francisco; and San Diego State University. He is presently on the faculty at Cabrillo College in Aptos, California. He has more than 30 years of experience representing employers in employment and labor law matters. His research interests include labor and employment law, human resource management, and issues addressing local government. His research has been published in a number of publications including Public Personnel Management, Police Chief, Labor Law Journal, Lincoln Law Review, Labor Relations News, HR News, and Public Personnel Review. He is a coauthor of several books including Legal and Regulatory Issues in Human Resources Management and Transforming Government Organizations: Fresh Ideas and Examples from the Field. He is a member of the Labor and Employment Law Section of The State Bar of California.

Notes:

1Community Oriented Policing Service, “The Impact of the Economic Downturn on American Police Agencies,” news release, October 2011, http://www.ncdsv.org/images/COPS_ImpactOfTheEconomicDownturnOnAmericanPoliceAgencies_10-2011.pdf.

2Jillian D’Onfro, “An Inside Look at Google’s Best Employee Perks,” Inc. (September 2015), http://www.inc.com/business-insider/best-google-benefits.html.

3The White House, “Fact sheet: President Obama Launches New TechHire Initiative,” news release, March 9, 2015, https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2015/03/09/fact-sheet-president-obama-launches-new-techhire-initiative.

4“Suspect Fatally Shot by Police Had Phone, Not Gun,” San Francisco Chronicle, January 3, 2016.

5Gordon Friedman, “Oregon Shooting Details to be Released Tuesday,” USA Today, March 7, 2016, http://www.usatoday.com/story/news/2016/03/07/oregon-shooting-details-released-tuesday/81457744.

6Owen Ullmann, “There’s no Joy in being the Bearer of Bad News,” USA Today, December 30, 2015, http://www.usatoday.com/story/opinion/voices/2015/12/30/voices-theres-no-joy-being-bearer-bad-news/77943834.

7American Psychological Association (APA), “Negative Publicity Reduces Police Motivation But Does Not Result in Depolicing,” ScienceDaily, October 27, 2016, www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2015/10/151027154941.htm.

8Leon Neyfakh, “There is no Ferguson Effect,” Slate, November 20, 2015, http://www.slate.com/articles/news_and_politics/crime/2015/11/ferguson_effect_it_s_not_real_but_urban_murder_spikes_are.html.

9Kevin Schultz, “Fremont Incident Is Caught on Video,” San Francisco Chronicle, June 4, 2016.

10Ibid.

11Phillip Matier and Andrew Ross, “SFPD Flight to the Airport: Officer Seek Safe Haven,” San Francisco Chronicle, June 14, 2016, http://www.sfchronicle.com/bayarea/article/SFPD-flight-to-the-airport-Officers-seek-safe-8150316.php.

12APA, ”Negative Publicity Reduces Police Motivation But Does Not Result in Depolicing.”

13U.S Department of Justice, Office of Community Oriented Policing Services (COPS Office), The Impact of the Economic Downturn on American Police Agencies, October 2011, 13, http://www.ncdsv.org/images/COPS_ImpactOfTheEconomicDownturnOnAmericanPoliceAgencies_10-2011.pdf.

14Robert Salonga, “San Jose: Police Will Lose Another 100 Officers by 2016, According to Projections,” The Mercury News, March 20, 2014, http://www.mercurynews.com/2014/03/20/san-jose-police-will-lose-another-100-officers-by-2016-according-to-projections.

15U.S. Department of Justice, COPS Office, The Impact of the Economic Downturn on American Police Agencies, 18.

16Ibid., 22.

17Kelley Dunleavey O’Mara, “San Anselmo, Twin Cities move Closer to Police Consolidation,” Patch, June 15, 2011, http://patch.com/california/sananselmofairfax/san-anselmo-twin-cities-move-closer-to-police-consolidation.

18J. Maher, “Sacramento Police Handcuffed by Budget Cuts,” News 10/KXTV, August 29, 2011.

19The Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve, “Introducing Actuarial Liabilities and Funding Status of Defined-Benefit Pensions in the U.S. Financial Accounts,” news release, October 31, 2014, https://www.federalreserve.gov/econresdata/notes/feds-notes/2014/introducing-actuarial-liabilities-funding-status-defined-benefit-pensions-us-financial-accounts-20141031.html.

20William Woska, “Public Sector Retirement Systems: Either Change or Consider Bankruptcy?” in Transforming Government Organizations: Fresh Ideas and Examples From the Field, eds. Ronald R. Sims, Jr., William I Sauser, and Sheri K. Bias (Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing, Inc., 2016), 142.

21R. Snell, State Pension Reform, 2009–2011, National Conference of State Legislatures, 2012.

22Martin Comas, “Cities Struggle with Rising Cost of Police, Firefighter Pensions,” Orlando Sentinel, April 27, 2013, http://articles.orlandosentinel.com/2013-04-27/news/os-police-firefighter-pensions-20130424_1_pension-fund-pension-costs-police-officers.

23“Shooting Deaths of Officers Spike 78%, Report Says,” San Francisco Chronicle, July 28, 2016.

24Brian A. Reaves, Hiring and Retention of State and Local Law Enforcement Officers – 2008, Bureau of Justice Statistics, , October 2012, https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/hrslleo08st.pdf.

25Ibid., 17.

26Ibid., 10.

27Ibid., 12.