All organizations, whether public or private, need to evolve and improve over time. In policing, this evolution is often described as “reform,” whereby individual police departments steer their officers and supervisors to approach their jobs differently to improve community trust through constitutional policing. For instance, officers might be asked to better document use-of-force incidents, more frequently engage with community members, or report misconduct when they see it. Such changes aim to introduce a new “way of working” or an internal culture that becomes second nature for department members. Cultural change is extraordinarily difficult in any profession, including policing, and police leaders would be well served to formulate a careful plan before initiating an intensive change effort.

In policing, organizational transformation may be initiated internally by the police chief or it may be imposed externally through a consent decree (a settlement agreement with active court monitoring) or civilian oversight bodies. Regardless of the situation, transforming the department’s culture typically requires extensive changes to policies, training, and data collection and analysis, as well as extensive stakeholder management with community groups and political leaders (and in the case of a consent decree, with a monitoring team and a federal judge).

Given the complexity and intense scrutiny that comes with reform, police leaders should avoid the temptation to “dive in” to a reform effort and should instead develop an integrated plan that defines measurable target outcomes and identifies the totality of the work required to achieve those outcomes.

This planning benefits the department in several ways. First, it allows the department to construct a realistic timeline for when internal and external stakeholders can expect to see results, both in policies and on the street. This can be critical to managing expectations about the work that lies ahead. In parallel, department leaders can use their plan to identify “quick wins” that will boost the credibility of the reform effort and build momentum for future projects.

Second, if a department believes it may be subject to a consent decree in the future, its reform plan can provide leadership with a clearer picture of the current state and gaps relative to the requirements that the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) is seeking to include in the decree. Ultimately, this knowledge allows the police department to negotiate provisions that are achievable and applicable to the organization and, therefore, more likely to be implemented sustainably. In the early days of a consent decree, a police department that has a point of view about what successful transformation looks like and how to get there is well positioned to collaborate with monitors and execute against an agreed-upon path forward. DOJ itself has stated that “valuable time can be lost at the beginning of the monitorship as new monitors and jurisdictions get up to speed on the nuts and bolts of implementing a consent decree.”1

On the other hand, a lack of careful planning can jeopardize even the most well-intentioned reform effort. A slow start, whether real or perceived, can create a narrative that the department is “not committed” or is “dragging its feet” on reform. This type of narrative can be difficult to overcome and can undermine the credibility of the reform effort and the department more broadly.

Preparing for Reform

While preparation requires considerable time and effort, a robust planning process can help a department get off to the right start in its reform journey. The following nine practical steps can help position an organization for successful reform.

Step 1: Create a “tiger team” to lead the reform planning effort.

The police leader’s first step should be to appoint a small team to spearhead the initial planning effort. This team should be composed of not only sworn leaders but also other sworn department members, professional staff, and potentially external experts who possess specific skills that will be relevant to the planning process, such as strategic planning, project management, internal communications, community engagement, data analysis, familiarity with IT systems, policy and training development, and internal audit procedures.

The reform planning team should consist of five to ten individuals with expertise across the listed domains.. Department leadership can consider implementing a governance structure around the team, with a “steering committee” composed of key department leaders, including the police chief, receiving regular updates on progress in defining the department’s plan.

Step 2: Define expectations and success measures.

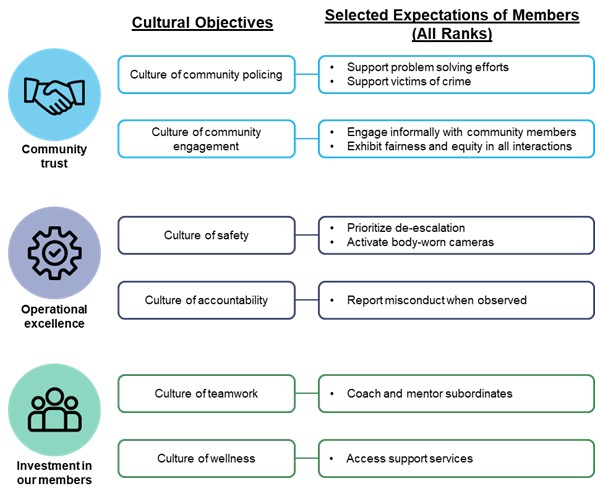

Organizational change should begin with the end in mind. The reform team’s first task is to identify at a high level the behavioral norms that leadership is hoping to instill among department members. Examples might include prioritizing de-escalation tactics or reporting misconduct when observed. These expectations will serve as the north star for the success of the reform effort. Figure 1 provides examples of these high-level expectations and how they might map to broader cultural and strategic objectives.

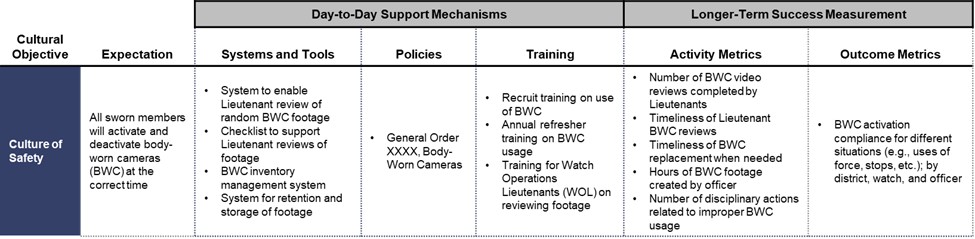

Once a full list of expectations has been defined, leadership should create an inventory of the policies, trainings, systems, and metrics that will be used to document or reinforce each of the expectations (see Figure 2). Specifically, which policies will need to be updated or newly created to reflect expectations? Where in training will the expectations be reinforced? Which systems and tools should be put in department members’ hands to help them achieve these expectations? (Examples might be updating a form to allow officers to document a specific action or implementing a software application that enables supervisory reviews of body-worn camera footage.) Finally, which metrics will the department track to measure progress?

Metrics are critical to organizational transformation. If closely managed, well-defined metrics can incentivize desired behaviors. Consent decree monitors also rely on data to determine whether the department is in full compliance with the decree. To that end, an agreed-upon list of metrics can align the interests of all involved parties early in the process.

Departments should list two types of metrics for each expectation. Activity metrics measure whether department members are following prescribed processes. These metrics are fully in the control of individual department members and can be used to hold leaders accountable for adhering to the new “way of working.” Outcome metrics, on the other hand, measure the impact of the new processes. They are not fully in the department’s control, but they should trend in the right direction if members are adhering to processes, as measured by activity metrics. Examples of each type of metric are included in Figure 2.

Step 3: Map relevant current state processes.

Once the full scope of the reform effort has been defined, the reform team can turn its attention to understanding how relevant processes work in their current state. This critical input enables leadership to identify gaps between the current state and the desired future state. Two types of processes are worthy of investigation in this phase.

First, the department should understand overarching processes that are likely to apply regardless of the reform topic. For example, the department should map its current process for updating policies. Who is responsible for policy updates? Who reviews policy changes and how long does this process take? What is the process for drafting an entirely new policy? A similar line of questioning could be followed for other broad topics, such as the process for developing and delivering a new or revised training curriculum.

Second, the department should map relevant processes that are unique to specific reform-related topics. For example, if one goal is to create a culture in which members report misconduct, the reform team should understand the current process for a department member to submit a complaint. The team can use the full list of policies that were identified in Step 2 to create a master list of subject matter–specific processes that should be mapped.

Step 4: Conduct a data and IT gap analysis.

Before the department can leverage data to drive organizational change, it needs to conduct a gap analysis for each metric included in its reform plan. Specifically, for every activity and outcome metric, the department should answer four questions:

- Do we collect the underlying raw data needed to track this metric?

- Do we report on the metric in any format (e.g., in a dashboard or a manually generated report)?

- Does anyone in the department currently analyze the metric to identify trends and opportunities for improvement?

- Is there a regular meeting at which leadership can manage performance against the metric (e.g., CompStat or other standing meetings)?

If the answer to any of the questions above is “no” for any activity or outcome metric, the department needs to plan for a project or series of projects to fill in the gaps. For example, if a particular metric is currently reported in the department’s annual report, but no individual or team is actively analyzing the metric for trends and, for example, making calls to districts that are underperforming on the metric, the department will need to establish processes for analyzing and managing performance against this metric.

In other cases, the department may collect the underlying data but in a manual or paper-based format that does not lend itself to reporting, analysis, and performance management. In this case, the department needs to initiate a project to digitize data collection, followed by subsequent projects to enable reporting, analysis, and performance management for that metric.

Though a painstaking task to complete, this metrics-focused gap analysis is likely eye-opening for department leadership, as it will reveal the significant amount work required to create the sophisticated data-driven management culture that is essential for sustainable reform.

Step 5: Create an internal communication strategy.

In Step 2, the reform team established an aspirational vision for the future of the department and how members will be expected to complete their jobs. As with any change, leadership must be sensitive to how and when it communicates to members about changes as they are implemented. Framing matters, so it is worth defining a formal internal communication strategy early to ensure that messages about change will resonate with members. The department should concurrently consider how this internal strategy will impact external communications.

The reform team should engage with communications experts to define two components of a strategy. A channel strategy informs how members will receive information about reform. This strategy should be informed by surveys, focus groups, or other methods of input from department members about their preferred methods of communication. The department should use this input to create a playbook for how it will roll out updates about reform; a major policy change that is likely to be unpopular with department members likely requires a different communications approach than a change that will be well received by members.

Messaging strategy defines the specific terminology to be used and, importantly, the terminology to be avoided in describing specific aspects of the department’s plan. For example, in some environments, terms like “reform” and “culture change” may carry unfavorable connotations and may need to be replaced with more neutral terms like “operational excellence.” The reform team should conduct interviews or focus groups with department members of varying ages, experience levels, assignments, and ranks to coalesce around an overall messaging architecture and the specific language choices that are most likely to galvanize, rather than dissuade, members to buy into and adopt the necessary changes.

Step 6: Develop a community input strategy.

No police reform effort is credible unless the community is actively involved. Consent decree monitors expect departments to make an authentic attempt to solicit as much community input as possible for policy and training changes. However, gathering community input requires specific skill sets and can be resource intensive. Prioritizing which topics should receive the most community input and prioritizing the format of that input can help balance the need for such input against resource requirements.

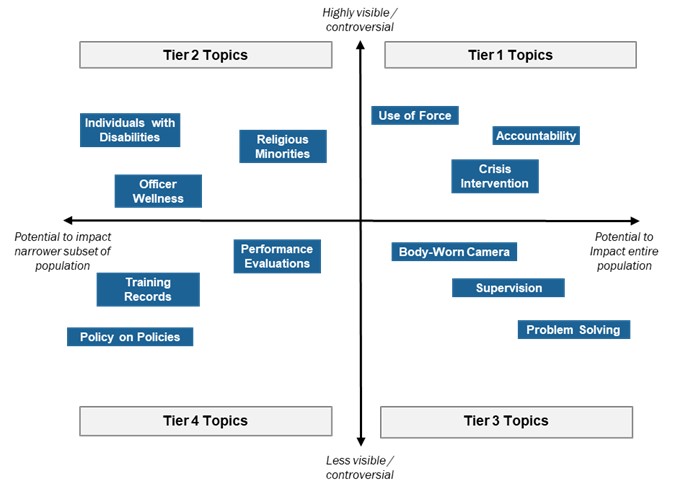

A simple framework to support initial prioritization is shown in Figure 3. This matrix plots various policy topics based on their likely level of community interest, and the relative number of people who are directly impacted by the policy. The reform team should plot each of the policies that were identified in Step 2 on this graph to create an initial tiering.

Tier 1 policies in the upper-right quadrant will likely require the greatest commitment from the department to obtain community input. Depending on the department’s available resources, it might commit to creating long-term community advisory committees on each of these topics, in addition to posting the policy for public comment and conducting internal focus groups with officers. Partnerships with community organizations can also be a powerful lever to solicit greater participation in the input process. Policies in lower tiers may receive less resource-intensive input gathering methods, such as conducting surveys or solely posting the policy online for public comment.

The goal of this step is to form an initial view of what is realistic for soliciting community input, based on available resources. This proposed approach will have to be validated and adjusted based on feedback from community stakeholders and consent decree monitors, but at minimum, this approach puts the department on “offense” rather than relying on external parties to shape its approach to soliciting input.

Step 7: Prepare to manage the reform process.

The reform team should develop a point of view early in the process on how to manage the immense workload once the journey formally launches. The full reform effort may consist of hundreds of projects across dozens of internal units, which will collectively require careful integration and cross-functional collaboration. The reform team should address the following questions, at a minimum, to prepare for this complex management undertaking:

How will the broader executive leadership team be involved in the reform effort? Consider maintaining a permanent “steering committee” or other apparatus through which relevant leaders will be kept apprised of developments, make decisions, and clear roadblocks for project teams.

How will the department drive collaboration across functions (e.g., policy writers, training, subject matter experts like internal affairs, etc.)? Consider establishing cross-functional working teams on specific reform topics to break down internal communication silos. For example, a cross-functional team to address use of force might involve individuals from the force review unit, training unit, policy development unit, internal audit personnel, and other relevant stakeholders so that everyone can seamlessly share information and coordinate on use-of-force projects.

Under a consent decree, how will documentation be shared with the monitoring team? As with any legal proceeding, documentation is central to consent decree compliance. Departments under a consent decree need a clearly defined process for who needs to internally review documents (e.g., a draft of a new policy or attendance records at a community meeting) before they go to the monitor, how long these internal reviews should take, and how to manage document flow without relying on email as a document management solution.

Step 8: For consent decrees, form a point of view on compliance methodologies.

Once a consent decree monitor has been appointed, they will define their approach to measuring compliance with the decree. Some monitors take a granular approach in which they grade compliance at the individual paragraph level; each paragraph may have multiple “levels of compliance.” In Chicago, Illinois, for example, each paragraph must progress through three levels of compliance: preliminary compliance reflects policy implementation, secondary compliance reflects training implementation, and full compliance reflects operational implementation.

Regardless of the approach the monitor chooses, the department should use all the inputs gathered in Steps 2 to 7 to create its own point of view—for every paragraph—of how it will achieve each level of compliance. For example, if a particular paragraph requires the department to change how it interacts with individuals with disabilities, the department can document the specific policy that it will update (Step 2) and the community input that it will gather (Step 6) to achieve preliminary compliance. For full compliance, it can document the specific metrics that it will use to measure performance (Step 2) and how those metrics will be tracked, reported, and acted upon moving forward (Step 4).

The reform team should create this comprehensive compliance plan and share it with the monitoring team as early as possible to drive alignment early in the process. This creates a dynamic in which the monitoring team assesses the police department against the its own plan for achieving consent decree compliance; the department is again “playing offense” rather than relying on the monitoring team to drive progress.

Step 9: Create a realistic project plan.

All of the preceding steps provide the inputs needed to form a robust project plan to guide the reform effort. Specifically, by going through the planning process, the department now has (1) a picture of the totality of the work to be done (e.g., system improvements, data collection improvements, community input) and (2) critical assumptions to inform timelines (e.g., amount of time to budget for internal and monitoring team review).

Using these inputs, the reform team should list, in exhaustive detail, all the tasks to be completed and the approximate time that each task will take. It can then prioritize a subset of projects that can be started first and put firm dates against those projects. As backlogged projects are ready to be started, the tasks and approximate timelines are already identified, and the reform team can focus on identifying exact dates to launch and achieve specific milestones.

These comprehensive project plans will be critical to managing external expectations around the pace of change. The reality is that many of the projects required under a comprehensive reform effort will take months or even years to execute. Having a comprehensive list of tasks and timelines that lays all of these steps out clearly will make it much easier for leadership and external stakeholders to understand all of the work required; manage external expectations; and deliver on-time, quick wins in the early days of reform to set the stage for additional momentum moving forward.

Outcomes of Effective Preparation

All the work described previously is critical to an effective rollout of a comprehensive organizational transformation. It establishes the critical ingredients needed for successful reform: (1) alignment with organizational purpose; (2) committed internal and external stakeholders; (3) active project management; (4) aligned systems and infrastructure (people, processes, and technology); and (5) a foundation for continuous improvement and adjustment as the reform process proceeds.

In the end, police leaders will know that planning has been successful when they have achieved the following:

Understanding of the current state of internal processes on key reform focus areas, including policy development, training development, and subject matter–specific processes.

A complete picture of the work to be done. This planning framework ensures all the steps that must be completed to help officers achieve expectations are identified and documented, from community input on policy changes, to new systems or approaches to data collection, to updating policy and training, to internal and monitor reviews of deliverables.

The groundwork for a true change management effort. Organizational change is not achieved solely by gaining compliance with a specific consent decree paragraph. A true transformation requires extensive internal communication and data-driven performance management. This planning framework encourages departments to think beyond “checking boxes” and focus on implementing fundamental enablers of change.

Alignment with various external stakeholders (e.g., City Hall, monitoring team, community stakeholders) on the path forward. This planning framework provides a toolkit that allows the department to lead the charge on its own reform journey. Having a point of view on compliance methodologies, approaches to community input, and how long different projects will truly take positions leadership to manage expectations and make faster progress early on.

Police reform is a complex undertaking made under considerable scrutiny. Police leaders would be well served to implement a thorough planning process to help their department hit the ground running and build momentum for change. d

Note:

1 United States Department of Justice, Review of the Use of Monitors in Civil Settlement Agreements and Consent Decrees Involving State and Local Governmental Entities (2021).

Please cite as:

Sudip Singh, “Preparing a Police Department for Reform: A Practical Guide,” Police Chief Online, February 19, 2025.