Few things, if any, have evolved faster in the law enforcement community in recent years than the body-worn camera.

First developed in the mid-2000s, original models could be a challenge to wear, operate, and utilize. Video files were not always as secure or as useful as they could be.

“The systems were pretty simplistic back then,” recalled Jason Dombkowski, director of law enforcement relations with Utility Inc., a Georgia-based technology company that created the BodyWorn series of cameras, the sixth iteration of which was released earlier this year. “You turned the camera on and off manually, and you had the old docking stations for offloading data onto on-premise servers that weren’t very secure.”1

But even then, their value to both the officer and the public were abundantly clear—and only became clearer in the years to come. They are now a common part of the officer’s toolkit. According to the National Institute of Justice, 47 percent of general-purpose U.S. law enforcement agencies in 2018 had acquired body-worn cameras.2 For large police departments, that number increased to 80 percent. Those numbers have almost certainly grown in the intervening years.

There are a multitude of specific benefits associated with body-worn cameras, especially with police under increasing scrutiny by communities across the United States and beyond. Law enforcement agencies see body-worn camera footage as a powerful ally not only in gathering evidence but in demonstrating accountability to the public.

“It is well established that the use of body-worn camera video deters violence and thus enhances safety,” said Adam Liardet, managing director of Audax Global Solutions, a United Kingdom–based body-worn camera manufacturer. “With the provision of impartial, accurate evidence, these devices are used to speed up the justice process by reducing case report preparation and enabling time and cost savings.”3

Still, fresh challenges and opportunities continue to emerge. For example, as the so-called internet of things has become more widespread and sophisticated, law enforcement has become more connected, and in no way is that better demonstrated than by today’s body-worn camera systems.

“Fast forward several years, and you have the evolution of both the industry and the body camera itself,” said Dombkowski. “But then you start to see new pain points, like having a system that was not automated or connected like it could be.”

Fortunately, body-worn camera firms around the world are developing products that are responsive to modern social and technological environments, to ensure agencies and officers are protected and covered.

The Connected Officer

BodyWorn 6.0 includes a number of features designed to keep officers safe and in closer contact. The cameras can be customized based on each individual agency’s unique rules and practices.

“We specialize in being the solution that creates a connected officer,” said Dombkowski. “We specialize in policy-based recording. That means you show us your policy, tell us when you want the camera to come on, and then we tailor the system for automation, which turns that camera on for your officer. We’d never ask an officer to do something technology can do for them. And it minimizes the risk of human error and the risk of implicit bias, which is very important today.”

The camera uses artificial intelligence to “sense” conditions and is also plugged into the rest of an agency’s technology.

“Because it’s a smart device and a connected device, we can turn the camera on as they’re en route to a call for service,” Dombkowski explains. “We’re integrated with the CAD system. We can activate the camera through that CAD system. Or we could have the camera turn on when the officer answers the call for service, or once they arrive at the scene, or it could be when they get within 500 feet of the address they’re dispatched to.”

Using the same machine intelligence, BodyWorn 6.0 cameras can alert dispatchers or other officers of an officer-down scenario.

“Our device can determine if an officer is standing or in a prone position,” said Dombkowski. “The device is able to recognize when an officer goes down in the field. There’s a predetermined countdown, and after that it sets off a series of automated alerts while starting a recording, which goes back to capture up to two minutes of pre-recording footage, so you can see what the factor was that caused the officer to go down. We can also use GPS to find the exact location of the officer, then provide turn-by-turn directions to every officer

in the field.”

Among its other features are an accelerometer that can tell when an officer is in foot pursuit, and multilayered automation to capture use-of-force incidence, including a Bluetooth connection with weapon holsters.

Body-worn cameras can help officers save time in several different ways, some of which go beyond simply capturing video.

That’s the philosophy for David Wasserstrom, executive manager of Sentinel Camera Systems, based in Huntingdon Valley, Pennsylvania. Sentinel’s body-worn camera systems let users store files locally or in the cloud. All come with the necessary software included, making installation and operation a snap.4

Wasserstrom, who said his units were competitively priced compared to similar offerings, said documentation can occur much quicker.

“It allows the officer not to need to take notes because it’s on the video,” Wasserstrom said. “When he gets back to his office, he can look at it on the camera before downloading. It allows them to be more efficiently servicing the public by focusing on what’s going on rather than documenting it.”

An Industry Pioneer Evolved

Audax has been supplying public safety professionals with body-worn cameras since 2005. Today their products remain on the cutting edge with continuous streaming video. The company’s 20-1 Body-Worn Camera offers local recording and WiFi live streaming with no insecure tethering.

“The future of body-worn video revolves around secure, real-time, live streaming,” said Liardet. “Recording for later download obviously has its purpose and the continuity of the chain of evidence is vital, but in a fast-moving environment, simply being a few hours ‘old’ means it is of limited use in dynamic situation decision-making.…With the use of Audax Cameras, we offer decision makers the ability to track multiple deployed assets along with live simultaneous video and audio feeds.”

Docking stations are an important component that, according to Liardet, also do not receive enough attention. The Audax Digital Evidence Management System (DEMS) docking station allows users to fully manage their recorded media while collecting and storing digital evidence recorded on a body-worn camera.

“The docking station solution is a critical and integral part of a modern body-worn video system that’s importance is often overlooked,” said Liardet. “The Audax range of docking stations provide a simple, agile solution for those customers faced with poor or unreliable data transfer upload speeds.”

A Novel Approach

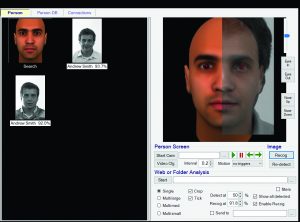

Body-worn cameras also can be used for other functions. In the case of Face Forensics, headquartered in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada, that function is facial recognition.

The idea for a body-worn camera that specializes in facial recognition has roots that predate body-worn video. The recognition technology developed by Face Forensics has been used in the United Kingdom to identify child abusers and elsewhere around the world in helping recognize faces of people from suicide bombers to drowning victims.

According to Iain Drummond, CEO of Face Forensics Inc., the idea to try the technology on a body-worn cameras came about after a fatal shooting incident outside Canada’s Parliament building in Ottawa.5

“After this incident, they wanted something that would provide as much early warning for these sorts of incidents as possible,” Drummond recalled. “They wanted a camera they could wear, but one they could keep hidden somewhere on the uniform. They wanted the camera to be able to scan faces within about 15 feet of the Parliament guards.”

The company’s Wearable Threat Detection (WTD) technology gives law enforcement the ability to identify individuals on a predetermined watchlist. Officers wear a small camera with a telephoto lens, as opposed to the more traditional wide-angle lenses. The camera is connected to a computer that checks images against the watchlist.

“If police are outside and a threat comes up, having this ability is useful,” Drummond said. “Our solution works fast, and because speed is a priority, it can help protect individual officers in that type of situation. It’s directly relevant to anyone who’s guarding anything.”

As technology and law enforcement needs continue to evolve and gain complexity, body-worn cameras will likely be a big part of the equation in many agencies for the foreseeable future. Manufacturers will keep their collective finger on the pulse to continue delivering high-quality solutions that benefit police and the public.d

Notes:

1Jason Dombkowski (director of law enforcement relations, Utility Inc.), phone interview, February 17, 2022.

2National Institute of Justice, “Research on Body-Worn Cameras and Law Enforcement,” January 7, 2022.

3Adam Liardet (managing director, Audax Global Solutions), email interview, February 14, 2022.

4David Wasserstrom (executive manager, Sentinel Camera Systems), phone interview, February 18, 2022.

5Iain Drummond (chief executive officer, CEO of Face Forensics Inc.), phone interview, February 17, 2022.

|

SOURCE LIST Please click on the companies’ names to go to their websites or visit the Police Chief Buyers’ Guide to request information from companies. |

||

|

|

|

|