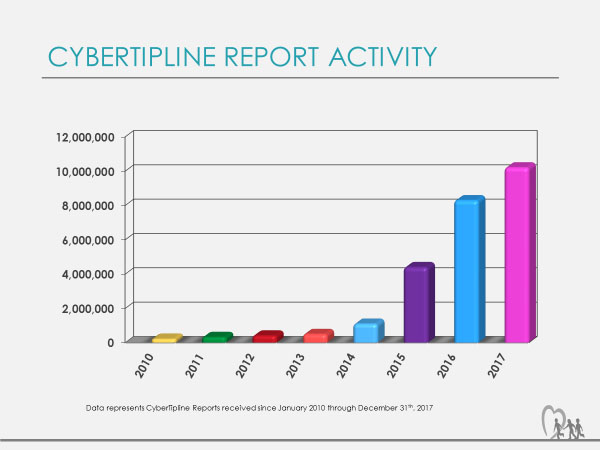

The most important cases that a law enforcement agency can investigate might well be those involving the sexual abuse or exploitation of a child. Internet crimes against children have exploded over the past decade with tens of thousands of victims being exploited online, making this issue a global challenge. The amount of data being seized by law enforcement in the conduct of these investigations is staggering. Since September 2002, the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children (NCMEC), Child Victim Identification Program (CVIP) has processed more than 240 million child exploitation images and video files seized by law enforcement agencies, of which 37 million were processed in 2017 alone.1 NCMEC’s CyberTipline received more than 10.2 million submissions in 2017, demonstrating an exponential growth in submissions.2

The challenges for law enforcement in the fight against child exploitation remain numerous and difficult. The logistical challenges of storing the ever-increasing amount of seized data are difficult enough, but processing the data for evidence, the cost and complexity of digital forensic software and hardware, training for digital forensic personnel, and the human toll of having to comb through the graphic displays of children being sexually abused is daunting for any agency. This is where the technology and ecosystems of Project VIC can make a difference.

Born as a grassroots effort in 2011 by a small group of investigators and industry partners to address the numerous challenges of investigating cyber-enabled child exploitation crimes, the project has now grown into a full-fledged force multiplier for agencies who adopt its principles.

At its heart, Project VIC promotes a victim-centric approach to child exploitation cases.

Law enforcement tends to think in terms of arrests, seizures, indictments, and convictions. This is problematic because, for this particular crime, there are vulnerable child victims. Before Project VIC, law enforcement agencies around the globe were largely offender-focused and, when coupled with a variety of other issues, this focus led to investigators often missing the exploitation material of new victims buried within the digital media seized from offenders.

The typical workflow for a child exploitation investigation started with information—either proactive (online undercover) or reactive (tip from NCMEC or other tip or lead systems)—that would lead to the execution of a search warrant and the seizure of the digital world of the subject. That digital world could easily include desktop and laptop computers, tablets, mobile phones, portable hard drives and thumb drives, cloud accounts, and so forth, resulting in gigabytes, sometimes, terabytes of digital information. It would not be uncommon to seize hundreds of thousands or even millions of image and video files in a single seizure. These seizures taxed law enforcement agencies’ capabilities to process those data efficiently. The path to least resistance led agencies to utilize semi-automated methods to locate “files of interest” using digital signatures called “hashes.” The limitation to solely utilizing this method to find digital image evidence is that investigators must know what they are looking for. Digital forensic examiners created sets of hashes or “hash sets” over time of files that were child exploitation images and videos. The problem is that by solely relying on these hash sets, it is unlikely that the investigation will find newly produced material, thus hiding new victims. At the end of the examination, the original digital evidence is placed into the evidence room. The unfortunate situation is that there could likely be thousands of unidentified victims sitting in evidence rooms around the globe.

Project VIC and its network of partners bring these victims to light by providing law enforcement investigators and digital forensic examiners with useful technological advancements to create higher levels of efficiency. These efficiency tactics open up valuable time that allows investigators and examiners to look for, identify, and rescue these previously unidentified child victims. One of the major issues facing digital forensic examiners is the proprietary nature of certain forensic software functions, preventing examiners from being able to utilize multiple tools in tangent for their examinations. The unfortunate fact is that no one digital forensic tool addresses the entire needs of the forensic examiner. Examiners must take a toolbox approach to thoroughly and successfully process a digital forensic seizure. One of the first things that Project VIC has accomplished is researching, evaluating, and adopting a data-sharing standard and a data-sharing model. The Project VIC Video and Image Classification Standard (VICS) is just that. Using the OData structure, Project VIC maintains a library of data models and technologies that vendors can implement in their software to make the transfer of forensic data from one software application to another seamless. This saves forensic examiners hours of time and frustration.

As David Haddad of the Phoenix, Arizona, Police Department explains, these efficiencies can be a game changer for child exploitation investigations:

Over the past few years, Project Vic and the efficiencies that have been born out of the initiative have fundamentally transformed the way our unit approaches digital forensics in Child Exploitation Investigations. We are tackling larger investigations and rescuing more children than ever before, while cutting our forensic backlog in half. We simply would not be able to operate at the level we are now without Project Vic and the interoperability fostered by the VICS standard.3

Through the VICS standard, Project VIC has created an ecosystem of tools and services that forensic examiners use in their daily workflow, creating a more efficient process with less frustration. Project VIC’s file categorization schema, which is standardized and has been adopted throughout the United States, provides a mechanism to classify files by their legality. Files that are categorized are placed into the Project VIC and are maintained for quality control on demand. These files are crowdsourced and hash set in the cloud, where standardized signature fingerprinting, technologies, and algorithms, like Microsoft PhotoDNA Image and Friend MTS “F1” video technologies are conducted. The results of this crowdsourced data set that has been analyzed and matched is a data set that provides workload reduction to the digital forensic examiner by allowing them to process files from their seizures against the categorized set. This can include illegal files, related files, and non-pertinent files, all of which will be automatically categorized based on the VICS data set. The investigator can review their own digital evidence and focus on finding new victims within the seizure. In the words of Special Agent and computer forensic examiner Michael Johnson with Homeland Security Investigations:

Project VIC, its ecosystem and the associated workflow has had a greater impact on both my work product and workload than any other tool or suite of tools in my 12 plus years of child exploitation investigation experience. The collaborative nature of information sharing of Project VIC has exponentially decreased my time involved analyzing seized evidence allowing me to focus more on victim identification and additional suspect follow up. The enhanced ability to rapidly locate, identify and react to new material is game changing in the pursuit of offenders and life changing for the victims rescued as a result.4

Mental Health and Well-Being Benefits

Child exploitation investigators and computer forensic examiners who deal with large amounts of media files depicting the sexual abuse and exploitation of children incur what is known as “vicarious trauma.” This mental stress is a secondary form of trauma. The repeated exposure can be very insidious, as viewing these images can have a direct and harmful long-term effect on the examiners.

Project VIC can help mitigate this repeated exposure to the brutalization of children. Historically, there has been no investigative or computer forensic methodology to minimize the exposure to these traumatic images and videos. However, Project VIC employs a methodology that flags each viewed image or video once an investigator or computer examiner has seen it, so that any other investigator or examiner using the Project VIC workflow and network does not need to view the photo, thus reducing each examiner’s exposure to these types of media.

Agencies invest heavily in all types of tools, training; and systems to help their officers more efficiently investigate cases, handle tactical situations, and manage logistics; however, very little is invested into the effects of child sexual exploitation investigations on the investigators. It is important that agencies invest in the mental well-being of their personnel. As Detective Eric Oldenburg of the Phoenix Police Department points out, the job requires more of investigators than simply technical knowledge, and the associated trauma can cause high turnover rates among child exploitation investigators:

Child exploitation investigators very frequently hear the words, “I don’t know how you look at that stuff” from veteran police personnel. This is an indicator that this type of work is reserved for those who are willing to put themselves in harm’s way, above and beyond that of the most dedicated police officer. Dedication is only the beginning. Technical skills, aptitude, and continuing training in an ever-changing field are requirements as well. Training personnel to be at optimal skill levels to work cases and rescue child victims, roughly 2 to 3 years of training and experience, is a substantial financial investment. Oftentimes, the 2- to 3-year time period is when exposure fatigue sets in and highly trained personnel move on to technological investigations that do not expose them to harmful material or vicarious trauma.5

Project VIC remains a strong advocate for reducing vicarious trauma and strongly supports policy makers and police executives in their efforts to address these issues. Project VIC is also actively assisting and working with many motivated and highly trained people in the fight against child predators and reducing personal exposure to investigative personnel. Project VIC is focused on decreasing exposure, while increasing investigative productivity.

Technology and the Future

Project VIC has seen great value in its work to standardize data formats and technologies with industry and law enforcement involvement and input. In doing so, Project VIC is putting forward best practices in the workflow regarding child exploitation data seizure and victim identification. Project VIC also collects technical requirements from investigators worldwide and passes these requirements to industries serving the child exploitation investigative community. This process builds a globally informed development of requirements that vendors can depend on to make sure their product offerings are meeting their customers’ needs and keeping up with current technological innovations.

Project VIC’s existing work in technology innovation is helping to push state-of-the-art technology forward in several areas including artificial intelligence, face and object detection and recognition, and voice and advanced video fingerprinting. These are just a few areas where Project VIC is able to crowdsource requirements and advancements from its vast community. These efforts ensure that industry leaders and government officials are focused on the real issues faced by law enforcement organizations, both large and small, who need to balance their budgets and resources. In this time of “do more with less,” Project VIC assists in making a discernable difference in an agency’s ability to address child exploitation investigations in a way that is victim focused.

In 2018, Project VIC completed its launch of the Global Alerts System. This new international system enables an investigator to deconflict data from seizures such as geo-location data or camera serial numbers. The system is designed to assist in cases where the victim is difficult to identify or where it is critical to determine if there is additional material in another investigator’s seizure that may lead to an identification of a victim.

These new systems and capabilities are possible only when everyone pulls together to make sure their data can work seamlessly together.

Project VIC furthers interoperability through the creation, distribution, testing, and instruction of technology, specifications, and best practices for use in the investigation of online sexual exploitation of children. Project VIC provides a forum and services that enable law enforcement agencies, non-governmental organizations, vendors, service providers, and others to collaborate on defining investigative needs. Project VIC assists with developing solutions to fill such needs and facilitates delivery of the solutions, so that investigations can more effectively be conducted.

Any agency with a desire to increase its efficiency and protect its personnel in the child sexual exploitation investigation realm can access and become part of Project VIC. See below for contact information.

Project VIC is made possible only by the input and participation of professionals seeking to combat child exploitation. Project VIC acknowledges all of the hard work of its early adopters, founders, contributors, and global supporters.

As a program at the National Association to Protect Children, Project VIC partners with global leaders in the fight against child exploitation. ♦

Notes:

1 National Center for Missing and Exploited Children, Child Victim Identification Program, weekly statistics week of April 10, 2018; National Center for Missing and Exploited Children, Child Victim Identification Program, weekly statistics week of December 31, 2017.

2 National Center for Missing and Exploited Children, “Online Enticement,” April 11, 2018.

3 David Haddad (detective, Phoenix, AZ, Police Department), email, April 11, 2018.

4 Michael Johnson (special agent, HSI), email, April 11, 2018.

5 Eric Oldenburg (detective, Phoenix, AZ, Police Department), conversation, April 2018.

Please cite as

Richard Brown, Eric Oldenburg, and Jim Cole, “Project VIC: Helping to Identify and Rescue Children from Sexual Exploitation,” Police Chief online, June 6, 2018.