With advancements in unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) technology, specifically nests, it may now be possible to deploy autonomous UAVs to assist officers with in-progress calls for service. Nests, simply put, are a protective home or base station where UAVs can stay charged and ready to be deployed from the field. Remotely deployed UAVs could be used to provide officers with real-time information, making their jobs safer and increasing the efficiency of crime-solving and documentation tasks.

Drones by the Numbers

Whether they are called UAVs, drones, unmanned aerial systems (UAS), or quadcopters, unmanned aerial technology is quickly becoming commonplace in the skies around the world. There are currently 1.1 million UAVs in the United States, and this number is estimated to triple to nearly 3.5 million by 2021. UAVs are also finding many uses in police departments worldwide. Currently, 347 law enforcement agencies in 43 U.S. states are using UAVs to assist officers in the field.1 Police agencies are using UAVs for search and rescue, traffic collision reconstruction, investigations of active shooter incidents, crime scene analysis, surveillance, and crowd monitoring.2 Despite this wide range of use cases, most law enforcement agencies currently deploying UAVs are using them only for preplanned operations and scene documentation. How can law enforcement take the use of UAVs one step further to integrate it into their response of in-progress calls for service? With an increasing number of officers killed in the line of duty, could UAVs make an officer’s response safer? Is there technology that would allow a UAV to autonomously respond to the scene of an in-progress call and provide aerial support to responding officers? If so, can law enforcement overcome the issues holding the integration of UAVs into general service back? The answers to these questions will determine the path forward for autonomous UAVs in policing.

Three Major Roadblocks

There are a number of both public and private industries trying to expand the commercial use of autonomous UAVs. For instance, Amazon and other delivery companies are already planning to use autonomous UAVs for deliveries.3 However, there are three major roadblocks for the integration of autonomous UAVs in the skies over the United States: Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) regulations, limited UAV flight time, and privacy concerns.

FAA Regulations

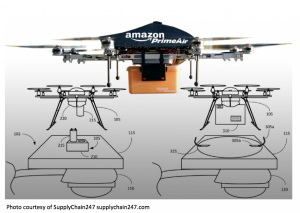

Two major FAA regulations are obstacles to the use of autonomous UAV technology: Beyond Visual Line of Sight (BVLOS) flight, and Detect and Avoidance (DAA). The BVLOS regulation states that a pilot must keep the UAV in visual line of sight at all times while in flight, thus preventing the possible of any autonomous or remotely directed flights.4 The FAA recognizes this regulation needs to be relaxed for the continued advancement of autonomous UAV technology. However, crash avoidance technologies such as Detect and Avoidance would need to be further developed and tested in order for the FAA to authorize autonomous UAV flights. With manned aircraft, a fail-safe is already built in with a human pilot being able to “see and avoid” if necessary. With unmanned aircraft, the pilot is on the ground or, in the case of autonomous UAVs, there is no pilot at all to “see and avoid” and take evasive action. Currently, “sense and avoid” technology is being developed to allow UAVs to talk to each other and sense and avoid when other aircraft come to close.5 To help the technology move forward, the FAA has already granted several exemptions to Amazon to develop technology and methods so they can make their autonomous “Prime Air” deliveries a reality. Police might be able to gain similar allowances if they join others to advocate for an expansion of these exemptions for public safety testing and deployment.

Limited Flight Time

The second major roadblock for the integration of UAVs into policing is the limited flight time of drones due to current battery technology. The average battery life of most UAVs sustains around 30 minutes of flight time. UPS, Chevron, Amazon, and other companies are looking to combat this limited flight time to make autonomous UAVs effective. To solve this issue, many of these companies are looking to deploy “nests” or base stations around various parts of their services areas. These nests would provide protection from the weather and the ability for a UAV to either charge its batteries or swap them out with a set of batteries being stored in the nest. This would require the UAV to be down only for a few minutes before going back into service. In commercial or public uses, nests could be placed throughout a region, allowing the drone to recharge without having to return to a central headquarters. The technology is not hypothetical—nest technology is already being used to monitor gas and oil rigs for equipment failures and to provide security for large areas.6

In addition, there is at least one company that specializes in deploying autonomous UAVs from nests These nests are managed through a software that allows users to view live videos, check the status of UAVs, and set and change predetermined missions.

This concept is very similar to what Amazon wants to accomplish with Prime Air. To that end, Amazon has already filed for several U.S. patents related to types of nest platforms or charging stations.7 One of the patents Amazon obtained was for a streetlight perch to be used by their delivery UAVs as recharging stations. Amazon also mentioned in the patent application that these perches could also be mounted on existing structures such as cell towers, church steeples, office buildings, parking decks, radio towers, telephone and electrical poles, and other vertical structures.8

Privacy Concerns

The third and probably most significant issue associated with the use of autonomous UAVs (at least for law enforcement) is privacy. When most people hear the words “drone” and “government” together, they immediately think of the predator drone used in theaters of combat: a weaponized UAV that can fly thousands of feet in the air surveilling the public undetected., a misconception that leads to fear of the technology.

In March 2013 the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) published a written statement to the U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee entitled, The Future of Drones in America: Law Enforcement and Privacy Considerations. In this statement, the authors point out that UAV technology is advancing rapidly, becoming more powerful and affordable and that the interest by police departments in using drones is increasing. The ACLU advocated for the strengthening of current laws to ensure UAV technology will be used responsibly and within constitutional values.9 The ACLU recommends, at a minimum, that the U.S. Congress should enact the following core measures:

-

-

- usage restrictions

- image retention restrictions

- public notice of UAV use

- democratic control of UAVs’ functions

- auditing and effectiveness tracking

- a ban on weaponization

-

One California police agency included privacy considerations in a pilot program to use drones for general law enforcement as a part of their proof-of-concept effort in 2018. The Chula Vista Police Department, which serves a city of about a quarter-million residents recently tested the viability and effectiveness of UAVs for in-progress calls. (See sidebar.) Their initial results are an encouraging sign that UAV could soon become a part of police deployment in the very near future.

Next Steps for Law Enforcement

Drones remotely dispatched from the field could be part of law enforcement’s future, but, before this becomes a reality, more law enforcement agencies need to deploy UAVs on a regular basis. As more and more agencies decide to deploy drones, they need to ensure their officers are properly trained and utilizing UAVs in a way that keeps public safety and privacy at the forefront of their deployment practices. Agencies should also seek out companies who are leading the way in UAV advancements to explore how to best integrate UAVs into law enforcement’s response to in-progress calls.

As more and more agencies decide to deploy drones, they need to ensure their officers are properly trained and utilizing UAVs in a way that keeps public safety and privacy at the forefront of their deployment practices.

To help the field reach a future in which UAVs are assisting officers routinely on in-progress calls, departments need to utilize UAVs, educate the public, lobby for legislative changes, and be willing to try new things like the pilot project in Chula Vista. If these efforts are made, within the next decade, there could be cities deploying UAV nests on the tops of fire stations and other government buildings, increasing officer safety and allowing agencies to better allocate their officers’ time.

Notes:

1 Bachman Justin, “How U.S. Police Departments Are Using Drones,” Daily Herald, April 15, 2017.

2 Marco Margaritoff, “Drones in Law Enforcement: How, Where and When They’re Used,” The Drive, October 13, 2017.

3 Kelsey D. Atherton, “Amazon Patent Lets Drones Perch on Streetlight Recharging Stations Like Pigeons,” Popular Science, July 20, 2016.

4 Guy Cherni, “Why Drone Use for Security Will Increase Significantly in 2018,” SecurityInformed.com, February 26, 2018.

5 Kelsey Atherton, “FAA Cautiously Suggests Relaxed ‘Line-of-Sight’ Rules for Drones,” Popular Science, May 4, 2015.

6 Christina Gomez and David R. Green, “Small Unmanned Airborne Systems to Support Oil and Gas Pipeline Monitoring and Mapping,” Arabian Journal of Geosciences, May 2, 2017.

7 Atherton, “Amazon Patent Lets Drones Perch on Streetlight Recharging Stations Like Pigeons.”

8 Nicholas Kristofer Gentry, Raphael Hsieh, and Luan Khai Nguyen, “Multi-Use UAV Docking Station Systems and Methods,” United States Patent and Trademark Office, Patent Full-Text and Image Database, July 12, 2016.

9 Laura W. Murphy et al., The Future of Drones in America: Law Enforcement and Privacy Considerations – ACLU Statement for the Record for a Senate Judiciary Committee Hearing (American Civil Liberties Union, March 20, 2013).