By now, most law enforcement officers have heard of procedural justice. Whether heard in the wake of a use-of-force incident, through the media, or simply from colleagues, “procedural justice” has become synonymous with fair and impartial policing. Unfortunately, in some circles, procedural justice is also synonymous with being out of touch with modern policing.

Academics, activists, and policy leaders frequently present procedurally just policing as a moral imperative in a democratic society—something that should be done because it is the right way to treat people. While this is undoubtedly true, presenting procedural justice in this manner to officers may lead to resistance because of the perception of procedural justice as “soft” policing that dismisses the harsh realities that officers face in their daily work.

Procedural justice, however, is not soft policing or a feel-good, politically correct fad. It is a valuable tool that all types of officers can use to improve their craft; create better relationships with community members; and improve outcomes for victims, society, and the officers themselves. Procedural justice is compatible with how officers do their jobs, but negative perceptions borne out of misinformation and assumptions have created an image of incompatibility. Reframing discussions around procedural justice can help to counter these perceptions and redefine procedural justice as a valuable tool that can be applied within any style of policing.

When police agencies introduce new policing practices such as community policing, the goal of the practice is to change the outcome of community-police encounters. Unlike many other policing practices, however, procedural justice deals with the process of policing, not the outcomes of policing. It’s not about what an officer does, but rather how he or she does it. Procedural justice does not preclude an officer from issuing a ticket, making an arrest, or using force as necessary. Instead of prescribing outcomes, procedural justice establishes four basic rules for interacting with community members:

1. Allow the person to explain his or her side of the story.

2. Be transparent about the decisions you make.

3. Show care and concern for the person’s safety.

4. Be respectful and avoid name calling or offensive terms.

Take, for example, a dispute between neighbors. An officer acting in a procedurally just way would talk to both people, listening to each disputant’s side of the story. The officer would mention that he or she is there to ensure everyone is safe and would call the disputants by their names or courteous tiles (sir, ma’am). Once the officer made a decision on how to handle the dispute, he or she would let both parties know the reasoning for that decision. Perhaps the dispute doesn’t rise to the level of a crime, and the officer suggests it should be handled through the apartment rental office. In this case, the dispute’s outcome is less important than the officer’s interaction with and treatment of the disputants. An officer acting in a procedurally unjust manner, on the other hand, would talk only to the person who called. This officer would say that it is not his or her problem to solve and that the complainant should “just work it out.” The officer would walk away without providing any further information. The outcome here is generally the same—the officer took no enforcement action and did not take a report—but the process was entirely different.

The difference between these two scenarios is not just the difference between acting in a procedurally just manner and procedurally unjust one—it’s the difference between an effective officer and an ineffective one. To be effective at controlling crime, officers must gather information, scrutinize complaints, and investigate even mundane situations. To get the information they need, officers must interact with the public in a way that encourages information sharing, rather than risks imposing dynamics that stifle it.

Procedural justice confers a variety of positive outcomes upon both police officers and the public they serve. The breadth of these outcomes, from improving officers’ instrumental effectiveness to enhancing the public’s confidence in the law enforcement community makes it a tool that can be used by any officer in any situation regardless of his or her policing style. This idea is explored herein using data from the National Police Research Platform (NPRP), which contains survey responses from officers, chiefs, and law enforcement agencies across the United States.1 These surveys were conducted between 2012 and 2015, and the data presented here represent the responses from 6,339 law enforcement professionals across 64 U.S. law enforcement agencies.

While there are many ways to categorize an officer’s policing style, recent research has focused on the warrior-guardian framework, which, in addition to being supported empirically, is well known and understood among the rank and file.2 Warrior mentalities prioritize officer safety and crime fighting. Those with this mentality see the police much like many see the military—as combatants fighting an enemy force. Those with a guardian mind-set, on the other hand, prioritize building relationships through non-enforcement actions. They see the police as a protector of society whose primary role is to protect the innocent, rather than fight an enemy.

While these two styles may appear to be at odds, many officers exhibit traits of both warriors and guardians.3 Grouping officers in any way, however, should not be done such that it forces moderate officers into the extremes. It is more beneficial to group officers into three general categories: officers who primarily exhibit warrior traits, officers who primarily exhibit guardian traits, and officers who generally have a mix of both traits.

Procedural justice is traditionally framed as a tool that enhances officer performance under the guardian mentality, which is more receptive to tactics that use communication over force. While data from the NPRP do find that officers with a guardian mentality are more likely to support procedural justice than officers with a warrior mentality, less than 6 percent of warrior officers actually oppose procedural justice.

| Figure 1 | |||

| Officer Style | Support Procedural Justice | Equally Support/Oppose | Oppose Procedural Justice |

| Warrior | 66.4% | 28.1% | 5.5% |

| Dual Role | 80.7% | 17.5% | 1.8% |

| Guardian | 89.5% | 9.9% | 0.6% |

| All Officers | 76.7% | 20.4% | 2.9% |

Most officers, regardless of their mentality, are generally supportive of procedural justice and very few outright oppose the practice. There are, however, many officers who do not fall into either of these categories—20 percent of officers neither support nor oppose procedural justice. These findings suggest two things. First, the location of an officer’s policing style on the warrior-guardian continuum does not dictate support for procedural justice. No group of officers outright rejects the idea of procedural justice. Second, a significant number of officers remain undecided, agnostic, or lack enough information to support or oppose procedural justice. Targeted efforts for increasing support among this group may be most effective.

Framing procedural justice in terms of the benefits it provides to the public and police, rather than its inherent moral value alone, could advance this objective. This approach grounds procedural justice as a tool in the patrol and investigative process rather than an ambiguous moral imperative. Research from across the world has shown support for five key benefits of procedural justice that reinforce its value as a policing tool.

1. Procedural justice can help the public to see the police as more effective crime fighters. A systematic review of the outcomes from 15 different research studies of legitimacy-enhancing interventions, such as procedural justice, found that satisfaction, confidence, and perceptions of police effectiveness all improved with the intervention.4 While some officers might not see community satisfaction and confidence in the police as a core goal of policing, the idea that procedural justice can lead to perceptions of the police as more effective at combating crime can be valued by all officers.

2. Procedural justice can encourage victims to report their victimization to police. A study of procedural justice in the island nation of Trinidad and Tobago found that the more procedural justice community members perceive in an encounter with police, the more likely they are to report a victimization.5 Without members of the public reporting crime, officers can’t effectively respond to crime. Much of an officer’s work is based on the response to public complaints, so being an effective crime fighter necessitates learning that a crime has been committed.

3. Procedural justice can encourage the public to participate in crime prevention programs. When the public sees the police as fair and respectful, people are more willing to participate in crime prevention programs.6 Must officers and police agencies support crime prevention activities, and public engagement in crime prevention programs is vital to their success.

4. Procedural justice can lead to increased cooperation from the public. Solving crimes requires information, and much of this information comes from the public. Interventions such as procedural justice can lead to increased public cooperation, such as providing information to police, reporting dangerous or suspicious activities, and willingly assisting police if asked. Fighting crime and protecting community members both require cooperation to be effective.7

5. Procedural justice can lead to increased compliance with officer directives, especially when dealing with offenders. A study of community-police interactions in Australia found that people who view police actions as procedurally just are more likely to comply with police directives.8 Further analysis found that this effect was especially true when dealing with offenders.9 Increased compliance can increase officer safety by reducing the need for force. While procedural justice won’t lead to 100 percent compliance, even small increases can be beneficial to officer safety.

With these potential benefits of procedural justice in mind, police leaders can begin to present procedural justice to their officers not just as the right thing to do, but also as a tactic with benefits for the officer, agency, and community. Most of what officers learn in the academy is presented as a tool to help them do their job, and procedural justice should not be an exception.

Increasing the Use of Procedural Justice

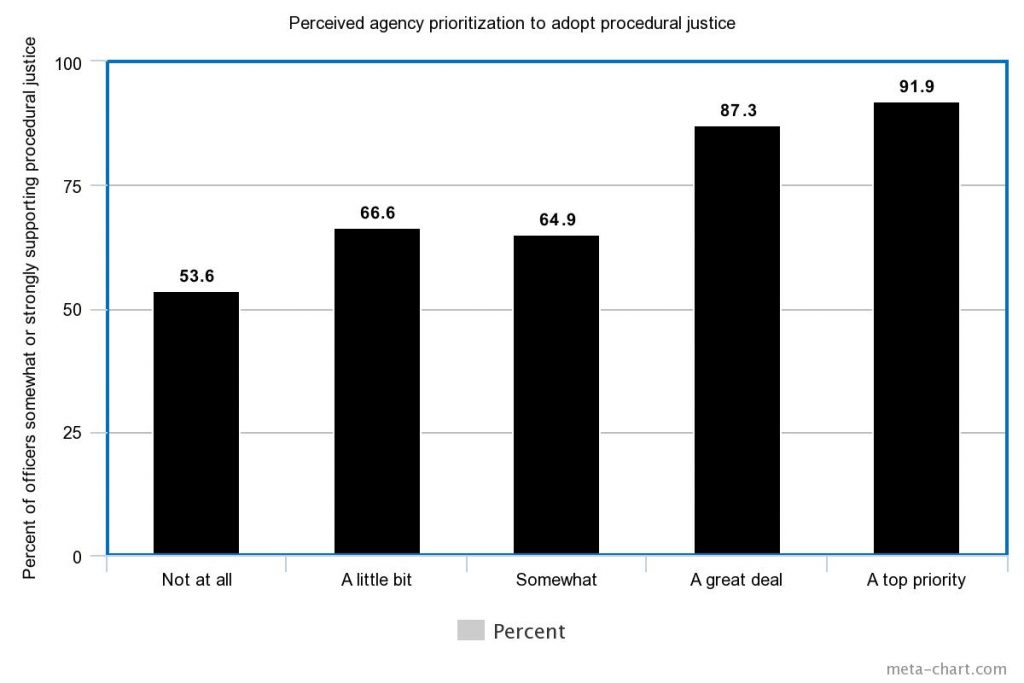

Police leaders who want to increase the use of procedural justice in their agencies will be heartened to know that data from the NPRP show that an officer’s support for procedural justice correlates with agency efforts to increase adoption. Among officers rating procedural justice as a top priority of their agencies, 92 percent support procedural justice. When officers see procedural justice as “not a priority at all,” support drops to only 54 percent of officers.

| Figure 2: As officers perceive procedural justice to be a higher priority for the agency, more officers support procedural justice. |

|

Increasing support for procedural justice is the first step to increasing the use of procedural justice. While the NPRP data do not directly address behavior in individual encounters, they do show that as support for procedural justice increases—so does an officer’s predisposition to use procedural justice during traffic stop encounters. Even though the actual use of any tactic in a community-police interaction is dependent on a host of factors, increasing a predisposition to use procedural justice should translate into increased use in the field.

Actual use of procedural justice in the field lags far behind the professed support from law enforcement officers. While the NPRP data show that nearly 77 percent of officers surveyed support procedural justice, observational studies in the field find that use is quite varied.10 For example, in 68 percent of community-police interactions studied, the level of participation by the community member was high or very high, indicating that the officer asked the person to tell his or her side of the story. Transparency in the decision-making process, however, was very low or low over 80 percent of the time. It is clear that there is still room for improvement in the use of procedural justice.

The idea of shifting the narrative surrounding procedural justice has found support in the example of those who use it the most—detectives. The NPRP data are full of surprises, and chief among them is the finding that detectives report using more procedural justice in encounters than officers in any other job assignment—even officers assigned to community policing units. But ask detectives if they support procedural justice and their responses are indistinguishable from officers in other units. Something about detectives leads them to use more procedural justice, even if they might not be realizing it.

While the exact reason for this difference is outside the scope of the NPRP data, it is possible that something about the investigative job lends itself to the use of procedural justice. As has already been discussed, procedural justice can lead to increased cooperation from the public. It could be that using procedural justice allows for a greater level of cooperation, which in turn leads to more information, a staple for detectives who are primarily tasked with gathering information from victims, witnesses, and offenders. Detectives, therefore, may be motivated to use procedural justice because it improves their ability to solve crimes.

This example shows how reframing procedural justice as a policing tool might lead to more use in the field. This is not to say that one should abandon the moral ground upon which procedural justice is based. It is genuinely the right thing to do and the way officers should treat community members. But increasing the use of procedural justice by framing it as a tool does not negate the moral benefits. Regardless of whether officers use procedural justice to fulfill a moral obligation or to enhance their work, procedural justice still benefits the public just the same.

This is not to say that procedural justice does not have its faults. There are, of course, situations where the use of procedural justice upends morality. An officer who uses procedural justice to induce cooperation and compliance while engaging in illegal behavior is clearly doing more harm than good. But using procedural justice motivated only by a desire to do better police work while still following the law provides benefits to officers and community members, and officers need not feel like they are giving anything up.

Switching the script on procedural justice from a moral imperative to an investigative tool may be simple in theory but can be tricky in execution. Knowing that a motivated leader can increase support for procedural justice is important, but having a leader talk about procedural justice as a tool is likely not enough on its own to change behavior.

The usual answer of “provide procedural justice training” is one option to influence behavior, but results of these trainings have been mixed. It could be that a procedural justice training focused on the benefits of the practice as a tool would work better, but even widely accepted training can fall by the wayside if not reinforced. Rather, a coordinated effort that includes traditional training combined with regular in-service and roll call refreshers may help to continuously convey the importance of procedural justice. Preliminary results from a study of the Enhancing Law Enforcement Response to Victims (ELERV) program suggest that motivated leadership and continuous training refreshers can help to integrate a “soft” program into police culture.11

Regardless of the implementation, simply changing the conversations around procedural justice is a step in the right direction. Knowing that an officer can be a fair and just warrior as easily as he or she can be a fair and just guardian empowers all officers to use procedural justice. Rethinking how officers see procedural justice is the first step to increase its use and expanding the benefits to both the police and the public. d

Notes:

1 More information on the National Police Research Platform Phase 2 data collection can be found online at the National Law Enforcement Applied Research & Data Platform website.

2 Kyle McLean et al., “Police Officers as Warriors or Guardians: Empirical Reality or Intriguing Rhetoric?” Justice Quarterly online, January 23, 2019.

3 McLean et al. “Police Officers as Warriors or Guardians.”

4 Lorraine Mazerolle et al., “Procedural Justice and Police Legitimacy: A Systematic Review of the Research Evidence,” Journal of Experimental Criminology 9, no. 3 (September 2013): 245–274.

5 Tammy Rinehart Kochel, Roger Park, and Stephen D. Mastrofski, “Examining Police Effectiveness as a Precursor to Legitimacy and Cooperation with Police,” Justice Quarterly 30, no.5 (2013): 895–925.

6 Michael Reisig, “Procedural Justice and Community Policing—What Shapes Residents’ Willingness to Participate in Crime Prevention Programs?” Policing: A Journal of Policy & Practice 1 (2007): 356–369.

7 Mazerolle et al., “Procedural Justice and Police Legitimacy.”

8 Lorraine Mazerolle et al., “Procedural Justice, Routine Encounters, and Citizen Perceptions of Police: Main Findings from the Queensland Community Engagement Trial (QCET),” Journal of Experimental Criminology 8, no. 4 (December 2012): 343–367.

9 Mazerolle et al., “Procedural Justice and Police Legitimacy.”

10 Tal Jonathan-Zamir, Stephen D. Mastrofski, and Shomron Moyal, “Measuring Procedural Justice in Police-Citizen Encounters,” Justice Quarterly 32, no. 5 (2015): 845–871.

11 Center for Victim Research, “Research-Practice Partnership in Law Enforcement: The Chattanooga Police Department and ELERV,” March 4, 2019, video, 1:27:28.

Please cite as

Matthew D. Kenyon, “Rethinking Procedural Justice: Perceptions, Attitudes, and Framing,” Police Chief Online, October 16, 2019.