One can easily imagine the rolling eyes and the sense of “here we go again” when another group of young people started behaving antisocially in a UK town!

However, this time it was different— certainly, how things played out suggested the police and community members needed to be more aware of other factors when faced with any similar issues in the future.

It looked as though these youths were having the best time. They were surrounded by their peers, they were drinking underage, and using illegal drugs. They were climbing the town’s Christmas tree and assaulting people who were just wandering by. This paints the town as some horrible place, when, in fact, Macclesfield in Cheshire is an affluent town founded on the money made from trading silk all the way from China. The town sits on a mainline railway and nestles on the border of the Peak District National Park.

Little did anyone know that that this group’s behavior was hiding something far more sinister. The Cheshire Constabulary’s “Beat Team” was assigned with long-term problem-solving tasks, which included tackling the issue of these young people who had started running over the roofs of cars and causing chaos.

Detective Constable Gina Volp created Operation Scarp with the primary goal of disrupting the illegal activities of these young people and putting measures in place to stop them from coming to the police’s attention again. That operation consisted of social worker and teacher support, along with support for the parents, too.

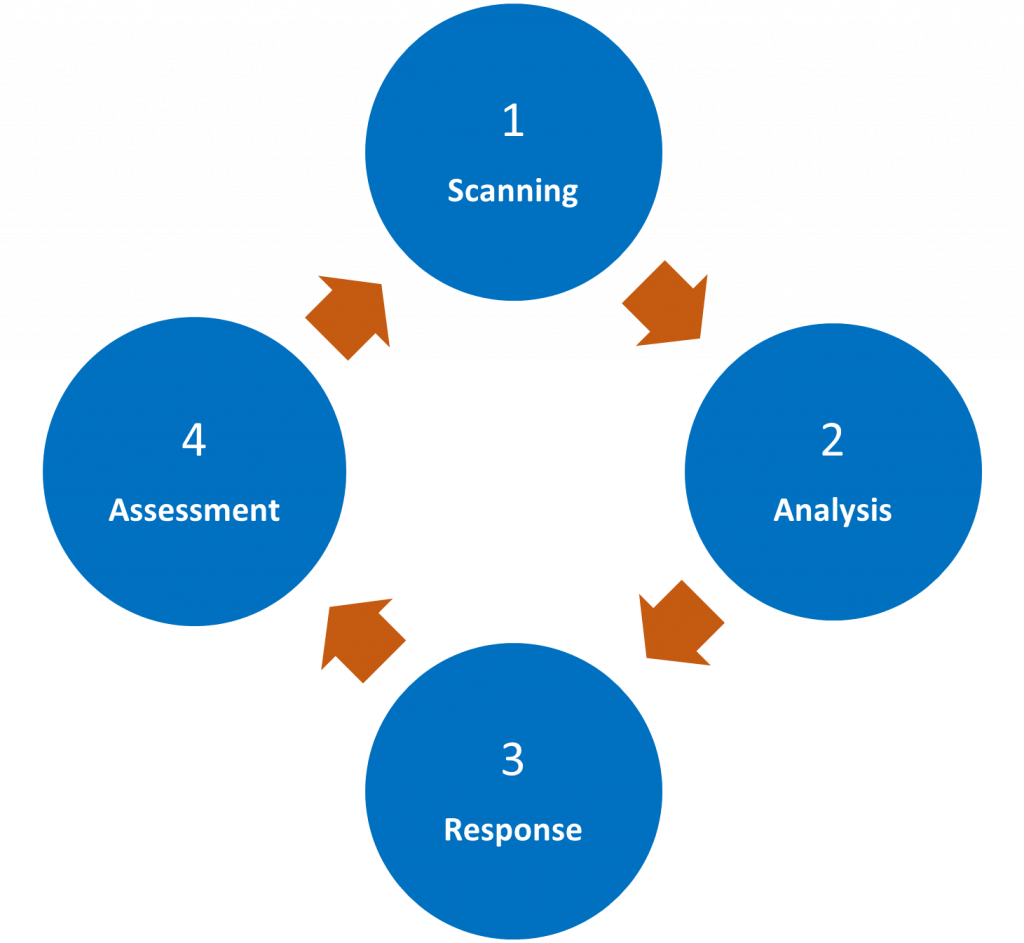

As a team that is set up to problem-solve, the members used the SARA model, filling in what they knew.

The SARA model is a decision-making model that uses four different elements—Scanning, Analysis, Response, and Assessment—which the Cheshire police use frequently. Each part of the model is important, but the Assessment stage is arguably the most important. It can sometimes feel alien to keep reviewing the work done, especially critically, as no one really likes to find issues. However, it’s that stage that allows a project team to learn and develop, save time in the long run, and get the needed results.

SARA Stage 1 – Scanning

There were near to 40 youths between 12 and 18 years of age involved in the illegal activities, with many not having previously come to the police’s attention. There was intelligence to suggest they were dealing drugs, carrying knives, and participating in other prohibited activities.

During the scanning stage, each child was given an action plan, and the police searched all their systems and those of social services too, to see what was known about each youth. A significant number of the older boys had been previously accused of some sort of sexual assault, and a significant number of the females had made (unrelated) allegations of sexual assault. This was a really worrying find, and clearly there were opportunities for other crimes to occur.

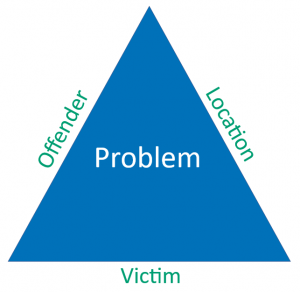

Working with other agencies on this problem was key, and considering the victim, offender, and location elements of the Problem Analysis Triangle showed that there was much knowledge to gain and to share among agencies and stakeholders.

The first step to gathering information was setting up regular meetings to try to avoid any detail being missed. The social workers began to report back that the young people were mentioning an older female who was dealing drugs to them while wearing an old school uniform.

When this alarming information came to light, the police encouraged all partners to begin to listen out for this female’s name and share anything they heard about her. In a very short space of time, it was discovered that this female was 18 years old but could easily pass for 14; she had a 14-year-old girlfriend whom she was buying underwear for and allegedly sexually touching. The older girl was also providing free drugs to some of the youths; and most alarmingly, she was taking young girls to hotel rooms, plying them with drugs and alcohol, and then bringing in males from a neighboring area to sexually exploit them.

Thus, during the assessment stage of Operation Scarp, the police realized that they had uncovered an entirely new problem, and Operation Waterside was born. This meant revisiting the SARA model, and essentially starting again and checking every element.

SARA Stage 2 – Analysis

Operation Waterside revealed 12 possible victims of child sexual exploitation (CSE). That really changed the whole field of play from a policing perspective. Unfortunately, the police had alienated some of these young people through targeting them as offenders. Police officers were the bad guys in the children’s eyes, and the Beat Team had been telling their colleagues on other teams that the youths were a problem. The Problem Analysis Triangle had to be readjusted as the “offenders” were actually the victims. The author found himself giving briefings to officers saying “Those young kids that assaulted you, that verbally abused you, that on one occasion racially abused you. I need you to understand they’re victims.”

It was a really hard sell, but essentially the fact that these youths were victims of such a crime went a long way to explain why they were lashing out at society. It was important that the police service was able to adapt quickly to meet the victims’ needs.

Using the Problem Analysis Triangle, the team came up with what was known about each leg.

Victims

The victims normally had a strained relationship with their parents, and they were mostly from broken families. They were not being reported missing when ideally they should have been, and they had withdrawn from other social and friendship groups.

Offender

The 18-year-old woman hadn’t previously come to the police’s attention, and, in fact, when the team was reviewing body camera footage to try and work out the link of where she had suddenly appeared from, she was found in the footage of a joint operation completed with partner agencies where she gave false details, citing she was 14. She could absolutely have passed for 14, but what was worrying was the fact she had chosen to lie in that footage, which meant that she knew what she was doing was wrong. She didn’t have the personal finances to be funding the hotel, the drugs. and alcohol—so where was the money coming from?

A big unknown were the men she brought to her victims, who the police knew only as “the Manchester males” as they had no names or supporting intelligence to identify these offenders.

It was unknown where the teen was getting her drugs from, but it was discovered that she was a big user of social media to facilitate “relationship building” with young girls.

Location

It was discovered that the suspect was operating out of one large chain hotel. The layout of this hotel was unfortunately well designed to facilitate crime. Upon walking through the entrance, visitors and guests are faced by an elevator and the helpdesk and staff are up one floor. Once a guest has a key (which operates the elevator and the assigned room), guests can easily go up in the elevator with whomever they want without having to pass any staff.

There were two cameras at the hotel, but neither of them worked, which added to the team’s frustration as they were keen to get images of the offender.

SARA Stage 3 – Response

The response was designed to target all three elements of the Problem Analysis Triangle. Although evidence would suggest that it’s only necessary to take out one of the elements to disrupt the problem, given the level, risk, and scope of the problem, it was decided to target each element separately and, crucially, at the same time.

Victims

Early on, safeguarding the victims was chosen over criminal outcomes.

Quite simply, the police are duty bound to both prevent crime and protect individuals and communities. By making safeguarding the top priority, the team knew that some of the actions taken would tip off the suspect that she was under investigation. Since there weren’t any victim complaints yet, this approach risked pushing her drug dealing and exploitation underground. This was a massive decision, and the team knew that it was essentially a gamble, but it was one they were very much willing to take for the sake of the victims.

In the UK, there have been a number of key cases involving CSE, and the police looked at these to help guide decisions. One of the most notable cases referenced was the the Rotherham Child Sexual Exploitation Inquiry, which had sent shockwaves through the UK policing system. That case had consisted of the organized child sexual abuse in a town in England from the late 1980s to the 2010s. The inquiry identified that the local authorities and the police had failed to act on reports of child sexual abuse for decades for fear of increasing racial tensions in the community.1 The Cheshire police felt strongly that now it was known that potential CSE was occurring, they couldn’t just wait until there was enough evidence to “spring a trap” on the suspect.

It was incredibly frustrating, as there was still no evidence, and the work about to be undertaken to help the victims might mean no evidence would ever be obtained. However, if safeguarding was put off in favor of getting evidence, the victims would potentially be exposed to more adverse childhood experiences (ACEs). Research shows that the more ACEs a child is exposed to, the more significantly their mental health, physical health, and future ability to become a functioning member of society is affected.2

Education was one of the primary methods of starting this intervention, specifically educating the young people both individually and through school presentations. While the team thought they’d identified all of the victims, they couldn’t be sure. Educating more children on the signs and dangers of CSE may help them recognize issues in their friends and alert an adult.

Part of the issue is that to a 13-year-old, hanging around with an 18-year-old is cool; didn’t see it as something to be worried about—the younger teens just thought it showed a sign of their own maturity. Adults obviously know differently. The goal was to make it so that, even if four out of five children thought it was cool, a seed of doubt was sown in at least one of those children, who then might alert an adult, which could trigger the safeguarding process.

The team also worked with young people individually. It’s known that, if a person is a victim of crime, especially of a sexual nature, he or she is likely to be victimized again in future.3 Therefore, it was key to to ensure that the victims truly understood what exploitation looked like. The partners worked with the youths to mitigate this risk, by discussing healthy relationships, drugs are never really free, how to be safe, etc.

The decision was also made to disclose the risk of CSE to parents, many of whom were shocked and had no idea of the age of their child’s new “friend.” They had invited in good faith a female who was dressed in a school uniform into their house, sometimes for a meal, never suspecting she was intent on causing their child harm.

The reaction from parents varied, with some angry and some relieved that they now understood why their children were behaving the way they were.

The police also worked with the parents around when to report their child missing. This wasn’t a popular decisions with colleagues because, after effort, the rate of missing reports suddenly shot up, causing additional work. However, a real picture of the problem was needed, and it could be achieved only by having the number of missing reports actually reflect the number of missing children.

Parents are often a protective factor, but, unfortunately, some are not. For these more “at-risk” children whose parents were unable to stop them from seeing the suspect because of insufficient boundaries, Child Abduction Warning Notices (CAWN) were put in place. This meant that if a specific child (for whom a CAWN was issued) was found in the presence of the suspect, the suspect would be arrested for abduction. This safeguarding work effectively tipped the suspect off that the police were on to her. It was also incredibly effective, as it also closed down options for children to go hang out with her since she wanted to avoid being found by the police.

Location

In the UK, the S116 Anti-social Behaviour, Crime and Policing Act 2014 directs hotels to contact the police if they suspect CSE is occurring on their premises. It also means the hotels have to provide details straight away, thus speeding up any investigation.

In this case, the hotel staff, it turned out, didn’t actually know what CSE looked like, so the police provided an informational guide and posters to put up in their offices.

The problem with the lift and layout of the hotel was addressed with the staff, pointing out how it was facilitating crime as the young people could be quickly taken up to rooms without passing a member of the staff. As a result, the hotel made it so the lift would hover at the reception floor, the doors would open, and then staff could see who was inside. The lift doors would then close again, and the lift would continue on its journey. This simple change could deter the suspect and actually make the hotel safer.

With the cameras fixed and the change to the lift, there was a chance the problem would be displaced, so warning notices and informational guides around CSE were distributed to all hotels in the town.

Suspect

The breakthrough came at the end of March 2019, when the suspect’s former 14-year-old girlfriend finally came forward to make a complaint of sexual assault. As a result, the suspect was arrested and interviewed. This was when some serious restrictions were able to be placed on the suspect. Her bail conditions prohibited her from being in the presence of any one under the age of 16 and her phone was seized.

Discovered on the suspect’s phone were extreme pornographic images and indecent images of some of the known at-risk children as well as images of unknown children.

The phone also gave the police access to information about the Manchester males who were facilitating the drug supply in the area. As a result, a number of warrants were conducted by colleagues in that community, and the main suspect was interviewed for conspiracy to supply controlled drugs. The prolific male was charged with seven counts of conspiracy to supply Class A and B substances, resulting in a prison sentence of four years and five months.

The female offender was charged with six offenses: three were related to drug supply and three to sexual offenses. She eventually pleaded guilty at court for the distribution of indecent images and was given a suspended sentence and a curfew and was put on the sex offenders register.

The team was under no illusions and understand that she may well have been a victim too, but she never engaged with the police.

SARA Stage 4 – Assessment

The challenge with assessing work done to tackle and prevent CSE is that, because it’s a hidden harm offense, using a decrease in reports of CSE as an indicator of success might not present a true picture.

The information received was that the at-risk young people were no longer friends with the suspect and they understood what an inappropriate relationship looked like. The hope was that, if they met someone new, and the relationship was of concern, alarm bells would ring in their heads.

Both families and schools reported improvements in the children’s relationships and behaviors. This was really positive, as it showed real change in the youths’ lives.

There was an increase in the reports of vulnerable young people missing, which meant that the requests to parents about reporting their children missing had worked. The increase was seen as a positive, as it indicated the parents were being better informed on when to appropriately contact the police. It was further helpful because it allowed the team to reassess and appropriately apportion partner’s resources more effectively. When it transpired that Child A, who was previously low on the “risk” ranking was actually missing four nights out of seven, the response was better targeted and became more effective. The police’s research showed that, after the suspect had come into these young people’s lives, there had been a 900 percent increase in the number of times they were reported as missing. After the response stage, however, the amount of times that the identified vulnerable young people went missing was around 84 percent. This was in comparison to the new number, which was more accurate.

The assessment also looked at the work completed with the hotels. Initially, there was a rise in the number of calls due to the hotel staff being better able to identify something of concern. On one occasion, a hotel reported that it had two young males who’d checked in and the staff wasn’t comfortable with them there. The police responding to that call were able to apply a protection order on one of the children as it became apparent he was being used to move illegal drugs. That then led to a whole different investigation to take out a new drug dealing team that had moved into Macclesfield.

Something that wasn’t anticipated was that, at one point in the response phase, the team received some intelligence that the suspect in the CSE case had migrated to a neighboring community and taken a few youths with her on a day trip.

However, because of a partner’s good relationship with the young people, the police were immediately notified about this through intelligence. The Cheshire police were able to liaise with the British Transport Police (who look after the rail network in the UK) and the neighboring police force to provide them with intelligence about the suspect and the vulnerable youths. They put markers on their own systems so their officers would be relayed the appropriate information, allowing them to take suitable action if the suspect or the vulnerable youths were encountered. The team also revisited the vulnerable youths’ parents and advised them that, if their children were visiting the town center of the neighboring area, they should be accompanied by an adult.

A Team Effort

In conclusion, the team learned a lot very quickly. They had already used the SARA model routinely, but this was the first time the model and its use was really tested. It was fascinating to see how, through its simplicity, the model continued to help the team plan and get the results they wanted. The pressure to get the right result for all involved was huge, and the team was constantly revisiting the SARA model for guidance.

It was also clear that policing is a real team effort, where not only was it absolutely vital to have partner agencies involved, but it was so important that all players routinely checked in with one another to ensure that every piece of crucial information was communicated. If the communication between the partners had failed, the whole operation would have too.

Lastly, a key factor was community engagement. Again, the team was well versed in this, but it was through this work that they could get key messages out to protect additional young people from harm. The engagement with younger audiences, many who already had a negative opinion of the police, was probably one of the biggest challenges. This took time— when time was of the essence—but without it, again, the team was likely to miss a crucial part of the case. d

Rob Simpson is a sergeant with Cheshire Constabulary and has worked in policing for over 20 years. His involvement in problem-oriented policing has resulted in his receiving the UK’s Tilley award and being a finalist for the USA’s Goldstein Awards. Rob Simpson is a sergeant with Cheshire Constabulary and has worked in policing for over 20 years. His involvement in problem-oriented policing has resulted in his receiving the UK’s Tilley award and being a finalist for the USA’s Goldstein Awards. |

Detective Constable Gina Volp joined Cheshire Police six years ago working in neighborhood policing where she lead investigations for the operation. Gina now works as a detective looking at serious and complex crime in the east of Cheshire. Detective Constable Gina Volp joined Cheshire Police six years ago working in neighborhood policing where she lead investigations for the operation. Gina now works as a detective looking at serious and complex crime in the east of Cheshire. |

Notes:

1”Rotherham Abuse Scandal: How We Got Here,” BBC News, June 22, 2022.

2Harvard University Center on the Developing Child, “What Are ACES? And How Do They Relate to Toxic Stress,” infographic.

3Deborah Lamm Weisel, Analyzing Repeat Victimization (ASU Center for Problem-Oriented Policing, 2005).

Please cite as

Rob Simpson and Gina Volp, “Applying the SARA Model in Operation Waterside: UK Agency Tackles Child Sexual Exploitation,” Police Chief Online, March 15, 2023.