For nearly three centuries now, law enforcement in democratic societies has based itself upon the policing principles and core ideas established by Sir Robert Peel in 1829.

Like many matters through the passage of time and the evolution of ideologies, principles can change or at least be reinterpreted. However, the Peelian Principles stand to the same, brilliantly uncomplicated interpretation today as they did when first penned. Until somewhat recently, a portion of the seventh principle became a bit obscured in relative importance to law enforcement administrators. In part, it infamously states that “the police are the public and the public are the police.” It’s undisputed that Peel understood the importance of community involvement alongside established police forces.

Law enforcement administrators can gain measurable ground in crime reduction—and immeasurable ground in building or improving community relations—by communicating with the people and businesses in their jurisdictions. This exchange of dialogue between law enforcement administrators and the public should be meaningful, genuine, open-minded, and continual. The public is often unaware of police procedure, contractual obligations from unions, intelligence-led policing tenets, limits imposed upon law enforcement by court rulings, and a multitude of other operational and often regulated restraints. Conversely, law enforcement often does not fully understand or appreciate what it’s like to live in a neighborhood where gunfire is a common, daily occurrence; where the theft of property isn’t an offense to even bother the authorities over; and where open drug dealing or brandishing of weapons is seen as “just another activity” occurring next door. What both sides do understand and agree on, however, is that everyone has a vested interest in reducing crime. It benefits the well-being of the public, of law enforcement, and of economies. So why aren’t law enforcement administrators talking and listening to the public more about how to reduce the crime in their own neighborhoods?

It’s an axiom that violent crime (particularly murders, aggravated assaults, and robberies) garner most of the attention of law enforcement resources and of public concern. These crimes are the ideal starting point for an agency to engage in meaningful, cooperative dialogue with the public on crime reduction strategies. There are unprecedented opportunities to fuse proven law enforcement intelligence-based strategies with the public’s concerns and their knowledge of crime and the tireless dedication of community organizations who are always willing to partner with police and the public at large.

The city of Youngstown, Ohio, located in the northeast portion of the state and comprising approximately 34 square miles, experienced violent crime at a rate higher than the national averages for at least the last 20 years, as partially demonstrated in Table 1.1

| Table 1: 2016 Rates of Crime (selected) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Crime | U.S. | Youngstown |

| Total Violent Crime* | 398 | 659 |

| Homicide | 5 | 19 |

| Aggravated Assault | 248 | 361 |

| Robbery | 103 | 234 |

| *Total Violent Crime represents the number of homicides + number of aggravated assaults + number of robberies. | ||

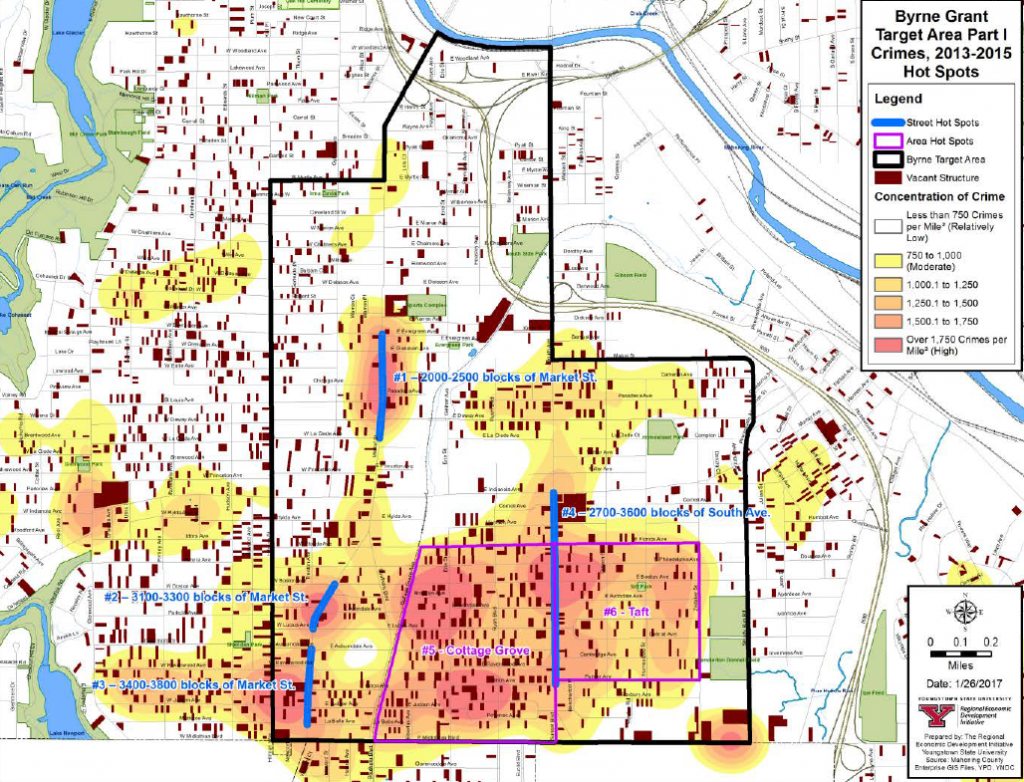

Disproportionately high to even those rates, however, has been violent UCR Part I crime on a portion of the city’s south side, comprising 2.7 square miles. This area equates to 7 percent of the city’s geography and 14 percent of the city’s population, yet accounted for 23 percent of the city’s homicides, 29 percent of aggravated assaults, and 26 percent of robberies.2 Within that geographical region was a smaller hot spot region (approximately 0.6 square miles). It had rates of homicide, aggravated assault, robbery, vacant housing, poverty, unemployment, and absence of formal education attainment higher than both the U.S. and city averages and was the highest concentration of those low rates in that larger area.3 The areas mentioned can be seen in Figure 1.

| Figure 1. Byrne Criminal Justice Innovation grant area (Youngstown Neighborhood Development Corporation, 2017). |

|

In 2016, the Youngstown Neighborhood Development Corporation (YNDC) conducted a house-by-house canvass within that larger area. The results indicated that 66 percent of residents felt crime and safety was a concern in their neighborhood and 50 percent felt that housing and property issues needed to be addressed to improve their quality of life.4 Obviously, the residents’ perception aligned with the data.

The city formulated a violent crime reduction strategy and realized that community input and involvement would be paramount to success. The President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing acknowledged the benefits that community-police collaboration can foster as it relates to crime reduction. Pillar 4 of the Task Force recommendations, Community Policing & Crime Reduction, opens with the statement “Community policing is a philosophy that promotes organizational strategies that support the systematic use of partnerships and problem-solving techniques to proactively address the immediate conditions that give rise to public safety issues such as crime, social disorder, and fear of crime.”5

Because of the high rate of violent crime in the target area and the ever-present concern of victimization by the citizens in those neighborhoods, the Youngstown Police Department, in cooperation with YNDC, and Youngstown State University (YSU), successfully applied for and was one of 12 cities that won a competitive $150,000 Innovations in Community-Based Crime Reduction planning grant through the Department of Justice. This planning grant was used to formulate a multimodal strategy to reduce violent crime by listening to and acting on citizens’ complaints of crime and social disturbance, conducting regular meetings with the public about crime issues, focusing extra patrols in the areas with the highest amount of violent crime, and reducing or eliminating property dilapidation and blight. After formulating the strategies and conducting a small implementation using the planning grant funds, the coalition further applied for and was one of four cities awarded the $850,000 Innovations in CBCR Implementation grant. Overall, this gave all partners the opportunity to utilize $1,000,000 to combat crime and blight within the city over a two-year period beginning in the fall of 2017. This initiative became known as the Community-Based Crime Reduction (CBCR) Project.

The theory that formed the basis for implemented strategies centered on the seminal work in 1979 by Cohen and Felson known as the routine activities theory. The theory postulates that in order for crime to occur, three elements must be present: (1) an offender with both criminal inclinations and the ability to carry them out, (2) a person or object providing a suitable target for the offender, and (3) the absence of guardians capable of preventing violations.6 If any one of the elements is removed from the equation then crime is not possible and, subsequently, criminal activity can be reduced or eliminated. It is at the neighborhood level that leveraging the cooperation of the public, especially the residents and stakeholders within the affected neighborhoods, becomes both the largest driver of crime reduction and of successful, sustainable community engagement. By attempting to impact crime on the small micro-spatial level, such as the small block groups the target area provided, it was posited that the crime reduction effects would spread to the larger urban landscape.

In line with intelligence-led and community-based violence prevention models, research has shown that successful initiatives and interventions to reduce crime include an array of methodologies, including targeted patrols (hot spot policing) and place-based policing.7 In essence, the more focused and specific the strategies of the police, and the more tailored to the problems they seek to address, the more effective the police [and the community] will be in controlling crime and disorder.8

To be successful, however, those targeted patrols must adhere to two operational elements. First, the intervention must be concentrated in the few hot spot areas generating a disproportionate amount of the crime. Then, the intervention must be driven by situational strategies that attempt to modify the criminal opportunity structure at crime and disorder hot spot locations.9

“The use of intelligence-led policing models and data-driven strategies, coupled with community and academic partnerships, are leading the way to realizing the ever-elusive goal of a crime-free society.”

The data in Youngstown was clear that the larger identified area, and specifically the target area, generated a disproportionate amount of crime. In the case of intervention in the target area, the situational strategies mentioned by Braga and Bond were included in the city’s implementation grant: the “small business safety initiative” that addressed employee safety education, crime prevention through environmental design (CPTED), and increased police communication and presence with business owners; the “residential property safety initiative” that addressed safety upgrades to homes, focused deterrence on repeat criminal offenders, and enforcement of rental property registries; the “community empowerment initiative” that sought to create new neighborhood associations and engage residents in local block parties and recreational activities; and the “neighborhood revitalization initiative” to tackle clean-up of vacant properties, demolition of blighted properties, and general neighborhood improvement.

These initiatives all included the essential element that they be community based and complement each other. In addition to the initial survey conducted by YNDC prior to the grant application, the partners continued to communicate with the public during the implementation period with additional neighborhood and business surveys, an open tip line for crime and quality-of-life issue reporting, and public meetings to assess overall satisfaction and hear additional crime reduction ideas. Moreover, community stakeholders were also invited to participate in the regular SARA (Scanning, Analysis, Response, Assessment) meetings undertaken by YPD, YNDC, and YSU not only to provide transparency in operations but also to ascertain the unique insight the stakeholders, community members, and businesses possessed to help the partners enhance strategies.

Most experimental interventions and research-based grants implement one mode of crime reduction strategy in a target area and measure it against a formalized control group area that does not receive such an intervention. It’s important to note that Youngstown’s CBCR Project was not originally applied for as an experimental grant but the unique nature of incorporating the varied crime-control theories and methodologies used in the project, coupled with a strong community focus, and being able to measure if they have an aggregated effect on reducing violent crime made it important to study nonetheless.

During the course of the grant’s implementation, the Youngstown Police Department used weekly crime maps of the target area, compiled by the YPD crime analyst, to deploy extra officers (typically, two at a time) to the area over a four-hour period. The four-hour period chosen for the additional patrols was based upon an aggregated three-year look-back of when most of the violent UCR Part I crimes occurred in the target area and the four-hour block with the highest total of UCR Part I crimes was chosen. While on patrol, the officers were foremost encouraged to stop by homes and businesses within the target area to speak with residents, business owners, and patrons so they could not only make positive community-police connections but also hear the concerns about crime in that area. Officers were also directed to utilize timely crime map information, any supplementary intelligence information provided, communications received by residents about possible criminal activity, and their own observations to conduct proactive traffic and pedestrian stops. The officers compiled a log sheet of their activities, which was later turned over to the YPD crime analyst for memorialization of the date, time, location, and type of law enforcement activities conducted.

Over the course of the project, officers participated in hundreds of extra patrols, personally contacted thousands of residents and businesses, and achieved thousands of criminal enforcement actions; simultaneously, YNDC (in cooperation with program partners) boarded up dozens of properties, along with demolishing, conducting code enforcement, or remediating blight of nearly a thousand other pieces of property.

Important to evaluating success was the time periods used for analysis. The beginning of multimodal interventions began in April of 2018 and ran through September of 2019, a total of 18 months. To ensure any data analysis was meaningful, an equal pre-intervention period of 18 months (October 2016 through March 2018) was used as the comparison time period. Data was compiled and analyzed through joint cooperation of YPD and YSU.

For this project, only the UCR Part I crimes of homicide, aggravated assault, and robbery (all pre- and post-intervention) were used and analyzed. The rationale behind this choice was a practical one as those violent crimes were most prevalent in that area and were of greatest concern to the public. Each block group in the target area (seven total) was sorted by crime type, intervention period (pre- or post-), and whether or not it was in the intervention area.

Measuring the changes in the rate of violent crime in the target area before and after intervention is a simple way to see if the multimodal interventions were effective. However, it would not allow us to gain perspective in regard to what may have been happening in other similar parts of Youngstown during the same period of time. For example, if all crime in the city decreased at the same rate as the target area, then the interventions would not have been meaningful. Here, it would have been scientifically ideal to have seven additional block groups in the city that could each be matched up to a target area block group in terms of violent crime rate, vacant property percentage, poverty percentage, and so forth.

The aim of the partners was not to be a formal experiment; therefore, there were no formal control areas included. However, a control block group was located for each of the seven block groups in the target area. Because reducing violent crime was the primary focus of the partners, it was given priority for measurement with an error rate of +/- 5 percent for other nontarget areas. Chosen as secondary and tertiary factors were percentage of vacant land and the rate of poverty.

It was an apparent and recognized limitation of this analysis that the sample number was low. However, as mentioned earlier, a primary goal was to provide a practical application to law enforcement professionals and community organizations wishing to engage in crime reduction efforts based on established academic research and effective practices. This typically entails a “before and after” comparison, which is how the data in this research are organized. After all, what most administrators want to know is simply if the interventions reduce violent crime in the targeted areas. Statistical analyses play an important role in these outcomes; however, not every police department or neighborhood revitalization group will have access or capabilities to conduct these types of tests.

To provide criminal justice practitioners with such a tool to make this determination, noted researchers and professors Jerry Ratcliffe and Andrew P. Wheeler published research titled “A simple weighted displacement difference test to evaluate place-based crime interventions.”10 Ratcliffe designed and published a macro-enabled Microsoft Excel spreadsheet titled ABC spreadsheet calculator. This free, downloadable spreadsheet permits the user to “evaluate the outcome of crime reduction operations that take place in a geographic area. The spreadsheet is optimized to work with operations that are focused in areas such as neighborhoods, housing projects, or crime hot spots.”11 It provides an overview of crime reduction efforts in an easy-to-read-and-interpret fashion.

Wheeler and Ratcliffe do not make any claim that this spreadsheet is the “end-all, be-all” new test for evaluating the effectiveness of crime reduction interventions. They note that a big limitation is that the control area and treatment area need to have relatively similar counts of crime and that it may be unable to identify statistically significant crime reduction, which is a problem endemic to all micro-place-based policing research. Despite some drawbacks, however, they note that the test is reasonable enough to use in practice, provides effective analysis, and that “the perfect need not be the enemy of the good.”12

So, were the multimodal interventions successful? Previous research indicates that crime interventions and blight remediation do have an effect, separately, in reducing violent crime when carefully planned and executed in the proper target areas.13 Table 2 begins to provide a perspective to answering this question.

| Table 2: Changes in Rates of Crime in Target and Control Areas Pre- and Post-Intervention | |||||||

|

Target Area |

Control Area |

||||||

| Crime | Pre | Post | % Change | Pre | Post | % Change | |

| Total Violent Crime* | 2,115 | 1,500 | -29.1 | 2,035 | 2,009 | -1.3 | |

| Homicide | 77 | 77 | 0 | 102 | 102 | 0 | |

| Aggravated Assault | 961 | 923 | -4 | 1,119 | 1,043 | -6.8 | |

| Robbery | 1,077 | 500 | -53.6 | 814 | 865 | 6.3 | |

| Note. Pre-intervention period is October 2016 through March 2018, and post-intervention period is April 2018 through September 2019. *Total Violent Crime represents the number of homicides + number of aggravated assaults + number of robberies. |

|||||||

There, the rates of total violent crime and aggravated assault each dropped post-intervention in both the target (- 29.1 percent and -4.0 percent) and control areas (-1.3 percent and -6.8 percent). The rate of homicide stayed steady between the target and control areas (0 percent change) and the rate of robbery decreased in the target area (-53.6 percent) but rose in the control area (6.3 percent). Table 3 shows post-intervention numbers of crime—total violent crime (33.9 percent), homicides (32.5 percent), aggravated assaults (13 percent), and robberies (73 percent)—were higher than in the target area. These numbers alone support the notion that multimodal interventions did have an effect in reducing violent crime.

| Table 3: Changes in Rates of Crime Between Target and Control Areas Post-Intervention | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Crime | Target | Control | % Change |

| Total Violent Crime* | 1,500 | 2,009 | 33.9 |

| Homicide | 77 | 102 | 32.5 |

| Aggravated Assault | 923 | 1,043 | 13 |

| Robbery | 500 | 865 | 73 |

| Note: Post-intervention period is April 2018 through September 2019. * Total Violent Crime represents the number of homicides + number of aggravated assaults + number of robberies. |

|||

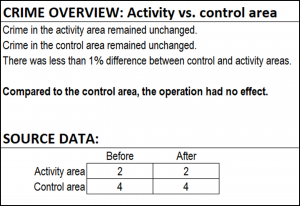

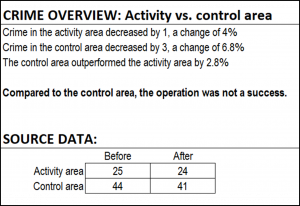

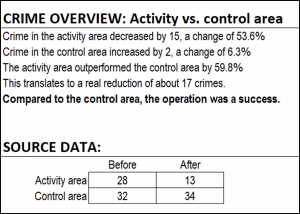

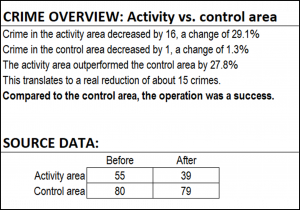

The aforementioned ABC spreadsheet calculator utilizes counts of crimes as opposed to rates since it provides a “real reduction” statement referencing how many crimes it calculates were reduced (if any). Figures 2 through 5 are derived from the ABC spreadsheet calculator using data compiled by the program partners in Youngstown post-intervention.

| Figure 2. Output for effectiveness of intervention on counts of homicide using Ratcliffe’s ABC spreadsheet calculator (2019). | Figure 3. Output for effectiveness of intervention on counts of aggravated assault using Ratcliffe’s ABC spreadsheet calculator (2019). | |

|

|

|

| Figure 4. Output for effectiveness of intervention on counts of robbery using Ratcliffe’s ABC spreadsheet calculator (2019). | Figure 5. Output for effectiveness of intervention on count of total violent crime (homicide + aggravated assault + robbery) using Ratcliffe’s ABC spreadsheet calculator (2019). | |

|

|

|

“Did it work?” is a question asked by countless chiefs of police, police captains, mayors, council persons, community leaders, news media, researchers, professors, and an array of other interested parties after a well-publicized violent crime reduction effort has concluded. “Did it work,” however, is a relative viewpoint depending on who asked and what “work” means to them. Because the audience asking these questions is often a diverse one, any similar endeavor to this violence-reduction effort should attempt to answer the questions from several angles to provide the most extensive, yet practical, perspective possible.

The CBCR Project for Youngstown was reasonably simplistic in what it sought to explain—that multimodal interventions in a high-crime area reduce overall crime in that same area relative to when, and where, intervention was not present.

Relating the successful interventions back to Cohen and Felson’s “routine activities theory,” YPD helped the program achieve success by increasing the presence of guardians (police officers) in the target area where the violent crime was occurring. YNDC successfully demolished vacant houses and remediated blighted and run-down properties, which helped remove people and objects that may have provided suitable targets for crime. Both organizations, in conjunction with YSU, also helped educate residents in the target area about how they could make safety upgrades through environmental design, how to help themselves from personally becoming victims of crime, and about other crime prevention strategies, thus removing themselves as “suitable targets.”

One point of concern is the lack of a “true” control area to analyze the effects of intervention more properly. Here, seven block groups were chosen that matched the target area block groups within 5 percent of total violent crime. During the period of time being looked at, however, actions to these control areas by both YPD and YNDC continued: YPD did not cease saturation patrols to hot spot zones outside of the CBCR area when the need arose, nor did YNDC cease all blight remediation in other parts of the city. It is irresponsible to deny extra patrols, code enforcement, and quality-of-life improvement pursuits throughout other areas simply for the purpose of studying its effects in a concentrated locale. Valid, however, is that the intensity and amplified frequency of such activities throughout the rest of the city did not compare to the directed, planned, and significant efforts that took place within the target area.

In addition to the unique nature of studying the effects of multimodal interventions in the target area simultaneously, this project was also the first found in the literature that used Ratcliffe’s ABC spreadsheet calculator for the key portion of the project’s analysis. Moreover, the program was used in the practical approach intended by Ratcliffe’s design: Did crimes increase or decrease in the operational area compared to the control area, and by how much? The results supported the partners’ notion that multimodal interventions reduced crime in the target area. Overall violent crime was reduced by 29.1 percent, robberies by 53.6 percent, aggravated assault by 4 percent, and the count and rate of homicides remained steady. But for the fact that the two homicides occurred weeks before the end of the program, there would have been none in the target area.

Though highly successful in reducing overall violent crime and robberies in the target area, the reduction in aggravated assaults was less than the control area and homicides remained steady in both. In what ways is it possible that administrators of similar operations can address these potential shortcomings to an otherwise successful program? Gun violence and homicides tend to be target-specific in nature, so augmented focused deterrence efforts on those who commit or are known to commit gun crimes is an effective strategy to reducing both.14 Another brilliance of the CBCR project was that, though funded initially through grants, its initiatives and interventions can be done with little-to-no extra funding—simply cooperation and coordination.

For too long, the city of Youngstown had endured a fiercely disproportionate amount of violent crime that affected the lives of its citizens. Though the final answer to eliminating all such crimes will remain elusive to even the most gifted academic or the wisest philosopher, practitioners in the field of criminal justice and researchers have many of the keys to help open that door. The use of intelligence-led policing models and data-driven strategies, coupled with community and academic partnerships, are leading the way to realizing the ever-elusive goal of a crime-free society. Inherent to this strategy, however, must be the continued communication with, and eliciting the cooperation of, a community that not only needs help but wishes to be part of the solution. Though the answers collaboratively discovered may be imperfect or may not follow traditional conventions, if collectively built, using lessons learned, success will come. Though the answers we come up with together may not be perfect or may not follow traditional conventions, if we build them collectively using the lessons we have learned we know that success will come. Then, when the inevitable question of “Well, did it work?” is asked the answer will be “Yes, it did.” d

Notes:

1Federal Bureau of Investigation, Crime Data Explorer database (1989–2019).

2Youngstown Neighborhood Development Corporation (YNDC), Youngstown, OH Byrne Criminal Justice Innovation Planning Narrative, Implementation Plan and Work Plan (2017).

3YNDC, Youngstown, OH Byrne Criminal Justice Innovation Planning Narrative, Implementation Plan and Work Plan (2017); U.S. Census Bureau, “American Community Survey,” (search filters: violent crime reduction, community policing, data-driven policing, hot spot policing, place-based policing, blight remediation, intelligence-led policing, multimodal strategies, routine activities theory, administration, community stakeholders, community-based crime reduction, crime analysis).

4YNDC, Youngstown, OH Byrne Criminal Justice Innovation Planning Narrative, Implementation Plan and Work Plan (2017).

5President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing, Final Report of the President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing (Washington, DC: Office of Community Oriented Policing Services, 2015)

6Lawrence E. Cohen and Marcus Felson, “Social Change and Crime Rate Trends: A Routine Activity Approach,” American Sociological Review 44, no. 4 (August 1979): 588–608.

7Anthony A. Braga and Brenda J. Bond, “Policing Crime and Disorder Hot Spots: A Randomized Control Trial,” Criminology 46, no. 3 (August 2008): 577–607.

8Anthony A. Braga and Cory Schnell, “Evaluating Place-Based Policing Strategies: Lessons Learned from the Smart Policing Initiative in Boston,” Police Quarterly 16, no. 3 (September 2013): 339–357; Anthony A. Braga and David L. Weisburd, Policing Problem Places: Crime Hot Spots and Effective Prevention (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2010); National Research Council, Fairness and Effectiveness in Policing: The Evidence, eds. Wesley Skogan and Kathleen Frydl (Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2004).

9Braga and Bond, “Policing Crime and Disorder Hot Spots.”

10Andrew P. Wheeler and Jerry H. Ratcliffe, “A Simple Weighted Displacement Difference Test to Evaluate Place-Based Crime Interventions,” Crime Science 7, no. 11 (2018): 1–9.

11Jerry H. Ratcliffe, Reducing Crime: A Companion for Police Leaders (London: Routledge, 2019).

12Wheeler and Ratcliffe, “A Simple Weighted Displacement Difference Test to Evaluate Place-Based Crime Interventions.”

13Braga and Schnell, “Evaluating Place-Based Policing Strategies”; Braga and Weisburd, Policing Problem Places; John Jay et al., “Urban Building Demolitions, Firearm Violence and Drug Crime,” Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 42 (2019): 626–634; Bruce Taylor, Christopher S. Koper, and Daniel J. Woods, “A Randomized Controlled Trial of Different Policing Strategies at Hot Spots of Violent Crime,” Journal of Experimental Criminology 7 (June 2011): 149–181.

14Braga and Schnell, “Evaluating Place-Based Policing Strategies”; Braga and Weisburd, Policing Problem Places; Elizabeth R. Groff et al., “Does What the Police Do at Hot Spots Matter? The Philadelphia Policing Tactics Experiment,” Criminology 53, no. 1, (February 2015): 23–53.

Please cite as

Jason Simon, “Successfully Reducing Violent Crime with Multimodal Community and Police Engagement Interventions,” Police Chief Online, November 30, 2021.