We are at a pivotal moment in our country as it relates to police trust and legitimacy. To do nothing is not an option; to engage in a journey that has been challenging, risky, and has the potential to inform generations to come has been our responsibility and honor.

―Chief Greg Mullen, Chief of Police, City of Charleston, South Carolina

On June 17, 2015, at approximately 8:06 p.m., a young, white male who aimed to start a race war entered the historic black church in Charleston, South Carolina, and joined with church members in a Bible study. For the next hour, he would discuss Bible verses and interact with the 12 parishioners who were also present.

An hour later, at approximately 9:06 p.m., he retrieved a Glock .45 caliber pistol from a fanny pack and systematically began killing those who were in attendance. At the end of his rampage, nine individuals had been killed, leaving only five survivors. Of the three surviving parishioners, one had been purposefully left alive by the shooter to tell the story; two others, a mother and granddaughter, lay in the carnage pretending to be dead as they watched their family members and fellow church members die. The other two survivors, the pastor’s wife and young daughter, hid in a back office unknown to the shooter.1

As the scope and magnitude of this event became known to the community, its potential impact and consequences were immediately apparent. The determination and compassion of all the police officers and special agents who responded from multiple local, state, and federal agencies was also clear. Thus, the questions were centered around how the community would respond to this tragedy.

What occurred over the next 12 days was nothing short of remarkable. The grace, forgiveness, and unity that brought community members together from all walks of life to speak out against the shooter’s actions and intentions, and call for healing and reconciliation captured the interest and appreciation of people around the world.

In honor of those who were slain, in an effort to prevent future incidents, the Charleston Police Department (CPD) undertook an effort to engage the entire community in conversations—honest, raw, and potentially volatile discussions. The goal of these efforts was to further strengthen the relationship between community members and the police by increasing trust and legitimacy.

A Solid Foundation for Moving Forward

The foundation that helped make these difficult dialogues possible after the shooting had been laid five years earlier when the CPD developed an unconventional five-year strategic plan. In a then-innovative approach (now common for the CPD), the roadmap for the organization was created with broad-based community input. Stakeholders critical to the department’s success had their voices heard during the plan’s development; elected officials, business leaders, community members, and internal members gave generously of their time to help develop a strategic plan that incorporated priorities from all segments of the community.

The CPD identified five strategic directions for the plan:

1. Enhancing Community Safety

2. Creating an Exceptional Workforce

3. Advancing Technological Efficiencies

4. Creating Community Partnerships

5. Effective Resource Management

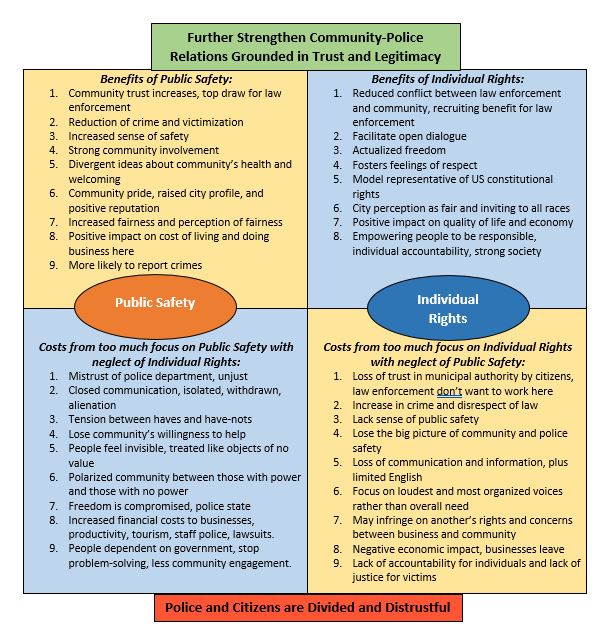

These directions make sense given today’s policing environment. They speak to the importance of both the “soft” (relationships) and “hard” (technology) aspects of work. But what made this plan unconventional was its basis in Polarity Thinking, an approach that leverages inherent tensions between points of view to create collaboration instead of the all-too-familiar conflict. Simply put, Polarity Thinking is a strategy of taking what are often seen as “Either/Or” topics (conflicts) and viewing them as “BOTH/AND” scenarios (collaborations).

The Illumination Project

The Charleston Illumination Project began as a heartfelt response to the shocking murders that occurred in the summer of 2015, which had created an internal desire within the CPD to “illuminate” the corners of their community that needed improved relationships between residents and law enforcement.

A Polarity Lens was a critical tool used throughout The Illumination Project, a radically participative effort to further improve community-police relationships by building trust and legitimacy. The integration of the BOTH/AND Polarity Thinking paradigm into the department’s leadership development, teambuilding, and individual coaching paved the way for applying it to this larger relationship-building effort.3

The purpose of the Illumination Project is “to further strengthen citizen/police relationships, grounded in trust and legitimacy.”4 Trust is a vital ingredient in all healthy relationships, especially one with the inherent tension of community safety (taking care of the “whole”) and individual rights (taking care of the “part”). Legitimacy speaks to a core element of the community-police relationship—police exercising their authority appropriately and community members believing they are being treated fairly.

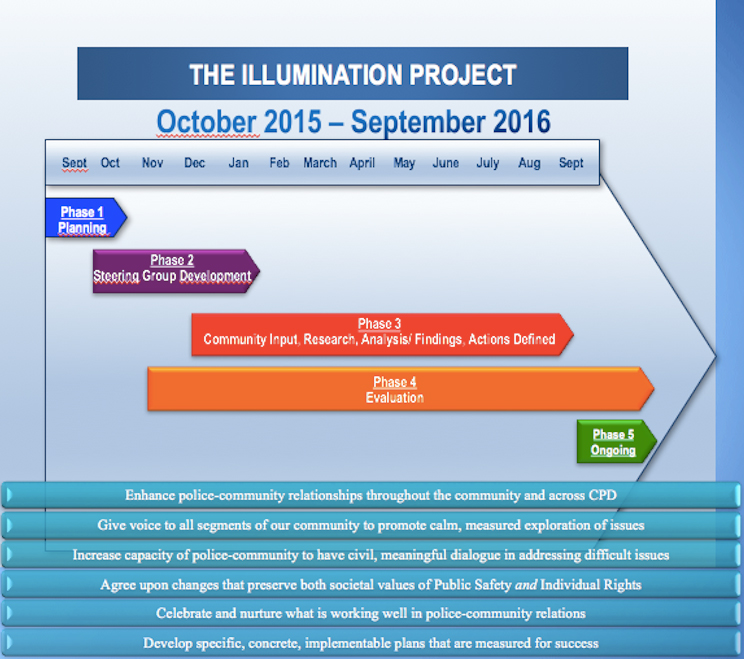

A five-phase process guided decisions and actions throughout the Illumination Project:

1. Planning and Development: Laying the groundwork for the project’s success.

2. Developing the Steering Group: Building the steering group leading the effort and the resource group that recruited people to participate in the process.

3. Research and Learning from the Community: Gathering information and learning from other studies and community contributions.

4. Evaluating the project: Measuring results, assessing impacts, and identifying lessons learned from the effort.

5. Making the model available for other communities: Sharing the methods, tools, and processes of the Illumination Project with other agencies and cities.

Process

The Illumination Project launch process unfolded over a 12-month period, with each of the five phases aimed at best leveraging the polarities to achieve stronger relationships. Once launched, the following months have been dedicated to implementing plans developed by Charleston’s residents and the police department.

Phase 1: Planning and Development

A consulting team for CPD drafted the project’s purpose, desired outcomes, and a suggested scope of work for project leaders. The two groups reached agreement on these elements as well as key community engagement strategies (which later came to be called “Listening Sessions”), the resources needed, and a draft Polarity Map focused on leveraging the tension between the competing demands of Public Safety AND Individual Rights (see Figure 3).

Phase 2: Developing the Steering Group

After the project’s scope was identified, the project management team selected a diverse group of key community stakeholders to serve as a steering group for the project. The group members, who were invited by the mayor to serve a one-year term, came from neighborhoods, business, education, faith-based organizations, politics, law enforcement, media, and other community establishments. Using the principles of Polarity Thinking, the steering group refined the project purpose drafted in Phase 1 and explored the inherent tensions between two sets of societal values:

• Public Safety and Individual Rights

• Respect for Law and Respect for People

The steering group’s preliminary work opened dialogue that served as a microcosm of public sessions to come in 2016. These community leaders guided the process development as they and the police department learned together how to create an approach that would engage community members throughout the city.

Phase 3: Research and Learning from the Community

Phase 3 entailed the most intensive work of the project. People needed to be recruited to attend and participate in the community gatherings, the Listening Sessions. In addition, learning was gathered from other cities and studies. The phase concluded with the development of a comprehensive plan and the early stages of implementation of strategies from that plan.

Studies on Improving Law Enforcement

External information was included in developing the strategic plan. The Riley Center at the College of Charleston conducted a two-part research effort on law enforcement that provided a national context for the Illumination Project. In 2015–2016, three major reports were published regarding community and police relations.

Each report was reviewed and a comprehensive list was created of all recommendations made by each organization in a collaborative effort between the Riley Center researcher and police department. These recommendations were then compared to CPD’s current practices, and the researcher worked with CPD to determine the progress the department was making on each recommendation.

The three following major reports from 2015 were reviewed:

• Police Perspectives: Building Trust in a Diverse Nation (U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Community Oriented Policing Services)5

• Guiding Principles on Use of Force (Police Executive Research Forum)6

• Final Report of the President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing (U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Community Oriented Policing Services)7

Public Relations and Community Education

The public relations and community education element of this phase involved using social media, targeted marketing, and clear messaging with the goal of making every resident in Charleston aware of this effort, its goals, and how they could become involved. In addition, 81 community influencers were educated in Polarity Thinking, thus creating a large pool of people who encouraged community members to attend a Listening Session. These influencers also had the skills to engage others in the city in Polarity Thinking conversations, which could be used to resolve other conflicts.

Listening Sessions

The Listening Sessions enabled community members to have their voices heard and gave the steering group opportunities to listen to the varied perspectives and emotions of the community. The vast amount of information drawn from these sessions was compiled into what would eventually become the strategic plan to further improve relationships between community members and the police grounded in trust and legitimacy.

These Listening Sessions have been the heart of The Illumination Project—small group BOTH/AND conversations between citizens and police that were guided by Polarity Thinking. The purpose of these conversations was to gather ideas about what both police and community members could do to improve their relationship. Active and persistent marketing of the Listening Sessions was a key to their success. Print media, radio interviews, in-person recruiting at city social events, and social media all played a part. A “Bringing the Illumination Project to You” approach of holding sessions for any group that would host one is one of many examples of how the project team strived to make it easier for people to have their voices heard. This experience, uncommon for many community members when dealing with police, led to many more people attending the sessions.

Agenda, Opening, and Welcome: A command staff member from Charleston Police Department (CPD) started each Listening Session by talking about why the session mattered and his or her personal vision of what the Listening Session could create and by thanking people for taking the time to come to the session. People take great meaning from small actions, even if they are not totally conscious of them, so police leadership needed to show appreciation for people attending and communicate that the police department is serious about taking these ideas forward and implementing them.

The sessions opened with a straightforward statement of fact: Local and national events have highlighted the troubled relationships between police and their communities. Clearly stating this context for the discussion, without “taking a side” kept the process and those managing it in a role of being “honest brokers” without ulterior motives.

Finally, the welcome portion of the sessions identified that the Listening Sessions had broad-based support from a wide variety of stakeholders critical to creating a preferred future. In addition, it was emphasized that everyone deserved to have their voices heard via an “agreement”: Say your piece and leave time for others to say their piece. (Don’t assume you have more or less to say than others.) Also, key was that participants agreed to speak to inform others, not try to persuade. For the Illumination Project to achieve its full potential, people needed to own the Listening Sessions and help shape the project.

Introductions: The purpose of including introductions in each Listening Session was to highlight the diversity in the small groups by learning everyone’s name, role, and organization. There also needed to be one personal question—something that went deeper than a standard name and rank. For example, a personal question was included that asked how long participants have lived in or loved Charleston and why they came to the session. This legitimized everyone in the room and helped people have their voice heard, because everyone had already “earned their place at the table” by virtue of being who they were. The question about how long people had lived in or loved their city was also purposeful. Participants had great pride in Charleston, so the question became a point of common ground that mirrored the project purpose of further strengthening these relationships in sustainable, substantive, and meaningful ways.

What Makes This Work Different: Time was allocated in the session to highlight what was different about this session and effort than other initiatives in which people may have been involved in the past. The project roadmap was explained, all of the people helping to lead the effort were shown on the screen, and pictures from other sessions were all shared to convey an important message—this is an open process and people are welcome to become involved in any way they want. There was no “inner group” calling the shots. Everyone had a contribution to make and the participants were going to be making theirs shortly.

Session attendees even received a quick lesson in Polarity Thinking. For example, it was explained about how both Public Safety AND Individual Rights were needed to create relationships, grounded in trust and legitimacy. All the terms used were clearly defined, which was another action intended to create a level playing field for all in the room.

Building Respectful Partnerships: Listening Session participants first answered two questions to build a common understanding of everyone’s experiences—both those they shared and those that were different. One of the results of this first conversation was increased empathy. Another was decreased labeling. For example, in one instance a comment of “All I see in you is a person with a gun,” translated to finding out that the police officer had a family, too, with two children who don’t want to go to sleep on time. These shifts in perception led to deeper and more honest conversations in the next section of the agenda when people were asked for ideas about how to improve their relationship.

The two questions participants were asked were the following:

1. We recognize the issues facing our community and the implications these have for all stakeholders. In light of the current environment, what are your concerns about building respectful partnerships between citizens and police?

2. We recognize the issues facing our community and the implications these have for all stakeholders. In light of the current environment, what are your hopes about building respectful partnerships between citizens and police?

Your Ideas for the Future: Whereas the first conversations focused on shifting perceptions, the purpose of the second Listening Session conversation was to suggest specific, concrete, and realistic actions that both community members and the police could take to improve their relationship. It was important to ensure that each person spent time identifying ways both groups could contribute in order to avoid all expectations for change resting with one group. Healthy relationships are two-way partnerships where each party both gives and receives.

In this part for the session, the participants were again asked two questions:

1. What suggestions do you have for police to further strengthen relationships with citizens? For example, what ideas do participants have for what police could start doing, stop doing, continue doing, and do more of (any of these)?

2. What suggestions do you have for citizens to further strengthen relationships with police? For example, what ideas do participants have for what citizens could start doing, stop doing, continue doing, and do more of (any of these)?

Prioritizing Ideas for Action: After each group completed the conversation, having been supported by a trained facilitator, they had separate lists for each stakeholder group (community members and police). All session participants then prioritized ideas based on the positive impact they believed each would have on improving the relationships. Each person was allotted five check marks for them to identify the actions each group could take that would make the biggest impacts in improving the relationship. Not only were people prioritizing their own ideas; they were doing it in a way that made it visible to everyone in the room. Once again, the meeting design was ensuring that decisions for the many were not going to be made by a few. These priorities were set using their own ideas plus one table next to their group.

The prioritized results across the total number of Listening Sessions were then combined and collated to become the foundation for a 2017–2020 Strategic Plan.

Report Outs and Closing: A short period of time was set aside for groups to share their work. It was important in the meeting design that there was time for small group facilitators to report out their group’s top two or three ideas, which allow people to hear their own ideas, further legitimizing their participation. They could also compare their group’s work to the work of other groups, leading people to recognize there were good ideas from every group in the room.

A list of future Listening Sessions was shared at the close of each gathering. This was one more opportunity to invite people into the process so they could contribute. Finally, the closing of each session included future plans that what would happen to the information generated, when people could expect to see it, and how it would be factored into the entire process.

Phase 4: Evaluating the Project

The Riley Center for Livable Communities, CPD’s research partner, assessed the impact of the Illumination Project and community member and police perceptions of each other were measured. There were also measures for success for each of the 86 strategies to be tracked over the three years of implementing the plan. (There has not been enough time yet to re-survey to measure perceptual shifts.)

Assessment and Modification: This critical step ensured that the input gathered from the community in the Listening Sessions was analyzed and prioritized. The steering group then reviewed it and integrated themes from the entire community into a draft solid, well-informed, and implementable plan.

Research, Analysis, and Findings: Research was conducted to learn from other cities and associations and then factored into the growing body of information.

Actions Defined Report and Implementation Plan: Insights gained from the information gathered were then prioritized, integrated, and compiled into a comprehensive strategic plan.

Phase 5: Creating a Model for Other Communities

Ongoing lessons learned from the Illumination Project will be communicated to the Charleston community and widely disseminated to other cities and police departments who are interested in establishing similar initiatives. This will include marketing efforts to inform other cities of the Illumination Project approach, providing them with the tools and support needed to implement it, and creating a community of Illuminated Cities that will continue to learn from each other into the future.

The Illumination Project’s Strategic Plan has five goals that closely align with recent studies in effective policing. Each goal has objectives, strategies, and measures of success.

• Goal 1 | Different Cultures and Backgrounds: Develop better understanding between community members and police officers of different cultures, backgrounds, and experiences to build mutually beneficial relationships.

• Goal 2 | Respectful, Trusting Relationships: Build a mutually respectful, trusting relationship between the community and the police.

• Goal 3 | Training Curriculum: Develop and implement a training curriculum to enhance community members’ and police officers’ understanding of each other’s roles, rights, and responsibilities.

• Goal 4 | Policies and Procedures: Develop and use best practices to improve community-police relationships through policies and procedures.

• Goal 5 | Community Policing: Expand the concept of community-oriented policing in all segments of the community.

Within these five goals, 86 strategies were identified to improve community-police relationships grounded in trust and legitimacy. Of these 86 strategies, 66 came from Listening Sessions, 12 from national study recommendations, and 8 from CPD staff. Identifying these strategies began with the 858 citizens who participated in Listening Sessions generating and prioritizing their own total of 2,226 ideas. From that list, the best ideas for police actions and community member actions that would improve the relationship were suggested as priority ideas to the two leadership groups for the effort, the Citizen Steering Group and Community Resource Group. Ten of these ideas were translated into strategies and recommended for immediate implementation in 2016. Public written comment sessions refined the highest priority ideas and the leadership groups endorsed these revisions.

Illumination Project Progress

Great progress has been made in Charleston through the Illumination Project to further improve relationships between police and the community members they serve—and much still needs to be achieved. The process made thus far was shared in a community-wide briefing in April 2017:

• Signed on as participant in the White House Police Data Initiative.

• Implemented policy of gaining written permission for consent searches.

• Implemented pilot “cite and release” program for a series of minor violations.

• Identified liaisons to work with various community groups to build relationships and share information.

• Formed a coalition to research and recommend actions dealing with social determinants for a healthy community (and started coalition meetings).

• Established new position of Community Resource Specialist working in five key neighborhoods in support of the Community Outreach Unit.

• Reviewed and analyzed five collaborative reform reports completed through the Department of Justice’s Office of Community Oriented Policing Services’ Collaborative Reform Initiative and compared them to current CPD policies and practices. Sixteen recommendations outlined in the reports by the assessment teams have been identified as applicable to CPD and are currently being implemented. Additional recommendations will be implemented throughout the remainder of 2017.

• Started a faith clergy council to work with the city on various issues and continue the successful faith-based components of the Illumination Project.

• With the Charleston County Library and the College of Charleston, rolled out training in Civil Rights history for officers.

• Facilitated Listening Sessions in 2017 for 501 citizens and many officers on understanding the community’s racial history.

The Illumination Project, if it is to realize its full potential, needs to become a regular way of working and living in the city of Charleston. When it becomes this type of ongoing process, the project will have ensured the work to further improve the relationship between the community and police with trust and legitimacy will never end. ♦

Notes:

1 Emily Shapiro, “Key Moments in the Charleston Church Shooting Case as Dylann Roof Pleads Guilty to State Charges,” ABC News, April 10, 2017.

2 Robert Jacobs, Lynnea Brinkerhoff, and Barry Johnson, “Whole Systems Transformation Through a Polarity Lens: An Idea Whose Time Has Come” in The Change Champion’s Field Guide: Strategies and Tools for Leading Change in Your Organization, 2nd ed., eds. Louis Carter et al. (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2013), 148–177.

3 Ibid.

4 Charleston, South Carolina, Police Department, “Charleston Illumination Project.”

5 Caitlin Gokey and Susan Shah, eds., Police Perspectives: Building Trust in a Diverse Nation (Washington, DC: Office of Community Oriented Policing Services, 2016).

6 Guiding Principles on Use of Force, Critical Issues in Policing (Washington, DC: Police Executive Research Forum, 2016).

7 President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing, Final Report of the President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing (Washington, DC: Office of Community Oriented Policing Services, 2015).

Please cite as

Greg Mullen et al., “The Illumination Project: Further Strengthening Relationships Between Police and Citizens,” The Police Chief (July 5, 2017): web article.