Over the past half-century, the role of police has expanded greatly, resulting in law enforcement officers being relied on as the default responders for many of society’s deep-rooted problems, including those stemming from substance use and mental health. Rethinking the role of police and the most appropriate response to a broad range of issues (e.g., loud music complaints, traffic accidents) requires a closer examination of what communities need. Yet, relying solely on reported crime incidents to understand the challenges a community faces significantly limits a full view of community needs. Though crime incidents may be easy to count given decades of standardization, they present an incomplete picture of what’s really going on in a community. Fortunately, a more complete picture can be had because nearly every community in the United States is already collecting the data. However, “the bad news is that nobody is using it.”1

The data alluded to are, of course, a jurisdiction’s computer-aided dispatch (CAD) data—referred to in this article as police events, though often colloquially referred to as 911 calls or calls for service (CFS). Event data are effectively an accounting of all the activity police officers engage in within their community, whether it is initiated by the police or in response to a request from a community member through 911. This activity certainly includes responding to crime, but it also includes many non-crime-related activities, such as addressing quality-of-life concerns or responding to traffic collisions. In fact, most police activity is not responding to crimes. Roughly 30 percent of police events are related to crime in general, whereas as little as 1 percent of police events are related to serious violent crimes.2

The question remains, however, if crime incidents present an incomplete picture of the community, and agencies are collecting rich data on the full scope of police activity and community needs, then why are police event data so often underutilized? A primary reason is that police event data are challenging to work with. Unlike crime incidents, there exists almost no standardization for recording and analyzing police event activity. Event data vary between and within departments, with each deciding its own policies and practices and almost no national guidelines or best practices to follow. Thus, though police event data offer a treasure trove—the next frontier—for understanding the evolution of community needs, analyzing the data in a robust and generalizable way currently presents significant hurdles.3

To explore these hurdles—and to illustrate the types of innovative work that can be done with effective analysis of police event data—a team from RTI’s Center for Policing Research and Investigative Science partnered with seven cities in North Carolina and South Carolina.4 This partnership, referred to as the Cohort of Cities, presented a unique opportunity to work directly with city management, police departments, and emergency communication centers to understand policing and community needs and to develop alternatives to police responses. The partnership also created space to work closely with local partners, such as police dispatchers, CAD system architects, and crime analysts to explore and deepen the understanding of police event data, allowing researchers to jointly develop and refine several recommended practices.

Though limited, there have been several recent research efforts focused on analyzing police event data. The Vera Institute of Justice conducted an in-depth exploration of police activity in two cities and partnered to develop a three-part report on some basics in analyzing event data.5 AH Datalytics has produced several reports related to analyzing police event data, including benefits of relying on crime reporting, how police spend their time, and publicly available agency assessments of police activity.6 More recent still, researchers leveraged police event data to explore questions around defunding the police, finding that community members call the police a lot and for many reasons and that there is generally a lack of other private or public resources available to respond to 911 calls.7

This article builds upon previous work to highlight several best practices when analyzing police event data. Police event data are often incomplete, unstructured, and complex. As a result, for agencies and researchers looking to explore community needs and police activity, certain steps must be taken with the data to meaningfully understand it.

What Are Police Events and Why Are They Challenging to Analyze?

Police events are records entered into a CAD system that document the details on what police officers are asked to address. Events largely come from two sources: community-initiated events are 911 calls for service, whereas officer-initiated events are the activities officers proactively undertake. Event records typically offer a timeline of information pertaining to a particular event; for example, an event record may include when and how the event began (source), a description of what the event is (type), when and which officer(s) respond to the event, any evidence of crimes that may (or, more often, may not) have occurred at the event, and how the event ended (disposition).

Despite the wealth of information possible with event data, they are incredibly challenging to analyze. There is almost no standardization across (or even within) jurisdictions on what and how data elements are recorded, which leads to jurisdictions developing their own approaches and data management practices.8 For example, in Tucson, Arizona, the department recorded more than 1,300 unique event types over a three-year period. The huge number of descriptions was due to evolving internal practices. For instance, when referencing domestic violence calls, descriptions changed from “10-codes” (e.g., 10-31w), to full text (e.g., domestic violence with a weapon), to abbreviations (e.g., DV-W).9 Part of this challenge is due to how CAD systems are governed, which is often organized within an emergency communications center (ECC). How the ECC is managed—and in turn how the CAD system is managed—varies: “[ECCs] all across the country operate in very different fashions, sometimes they’re under a police department, sometimes they’re under a regional authority.”10 Without clearly defined management and approval processes, CAD data structures and the values therein change sporadically and often without documentation, complicating longitudinal explorations of patterns of police activity. Further, there is an expansive and varied landscape of CAD software providers. Even within the same CAD software, there is variability as each agency will develop and iterate on its own conventions and data values.

Through the Cohort of Cities partnership, researchers had the opportunity to explore these issues in-depth with seven cities that ranged in size and population from about 50,000 to 500,000 persons. The event data that were analyzed covered a three-year period and more than 4 million total records across all cities. While there are many data elements recorded in a CAD system, three foundational elements that must be included in event analysis were identified: the event source, the type of the event, and the event disposition. Table 1 shows the variability of unique values for these three data elements across the seven cities.

Table 1: Range of Unique Values in Cohort Cities Police Event Data |

|||

| City | Event Source | Event Type | Event Disposition |

| C1 | 2 | 134 | 23 |

| C2 | 18 | 302 | 27 |

| C3 | 16 | 350 | 32 |

| C4 | 20 | 156 | 17 |

| C5 | 4 | 505 | 84 |

| C6 | 2 | 93 | 19 |

| C7 | 2 | 181 | 27 |

The variability shown in Table 1 is not unusual and will be encountered in CAD systems across the United States. Moreover, this variability presents clear challenges to understanding trends in a community—and certainly at the state, regional, or national level. To illustrate how these challenges can be addressed, examples and lessons learned from the Cohort of Cities partnership are provided.

Examples from the Cohort of Cities

There are many questions that can be asked of police event data. The focus in these examples is on the CAD data elements that best answered key questions that the partner cities wanted to understand regarding police activity and community-police interactions.

How often are police being proactive in the community?

Community-initiated events can provide insight into the needs of the community, whereas officer-initiated events can shed light on where and how police engage in proactive and discretionary activities. The event source data element in a CAD system differentiates how the event originated. The two primary categories are community- and officer-initiated events; however, often there are additional unique values to further differentiate within those categories. Across the partner cities, approximately 44 percent of all events were officer-initiated.

In the context of exploring alternatives to police responses or understanding officer discretion, the ability to differentiate between community- and officer-initiated events is key and requires only a binary indicator of event source. The measures of police activity resulting from community-initiated events do not examine police discretion and should be considered as wholly different in explorations of over-policing or disparate contact with certain populations. While some cohort cities measure event source as a binary value, others had up to 20 unique event sources—some of which were ambiguous or uninterpretable without assistance from system users and administrators. The careful definition of community- and officer-initiated events should be a priority for police event analysis and in the development of agency data infrastructure.

What services does the community need the most? What do police officers proactively do the most?

All event records in a CAD system include a brief description—often just a code or a few words—that describes what is happening and what behavior generated the call to 911 or officer-initiated activity. The event type can range from specific and clear (e.g., carjacking in progress) to broad and ambiguous (e.g., unknown trouble). The challenges are that there is no standardization on what the “right” event types are, nor is there a sufficient resource guide to which types of things should be categorized a particular way (as there is, for example, with the FBI UCR program for crime incidents). However, despite these significant challenges, event types are often used to make policy decisions, such as which events police will no longer respond to or which events will receive an alternative to police response.

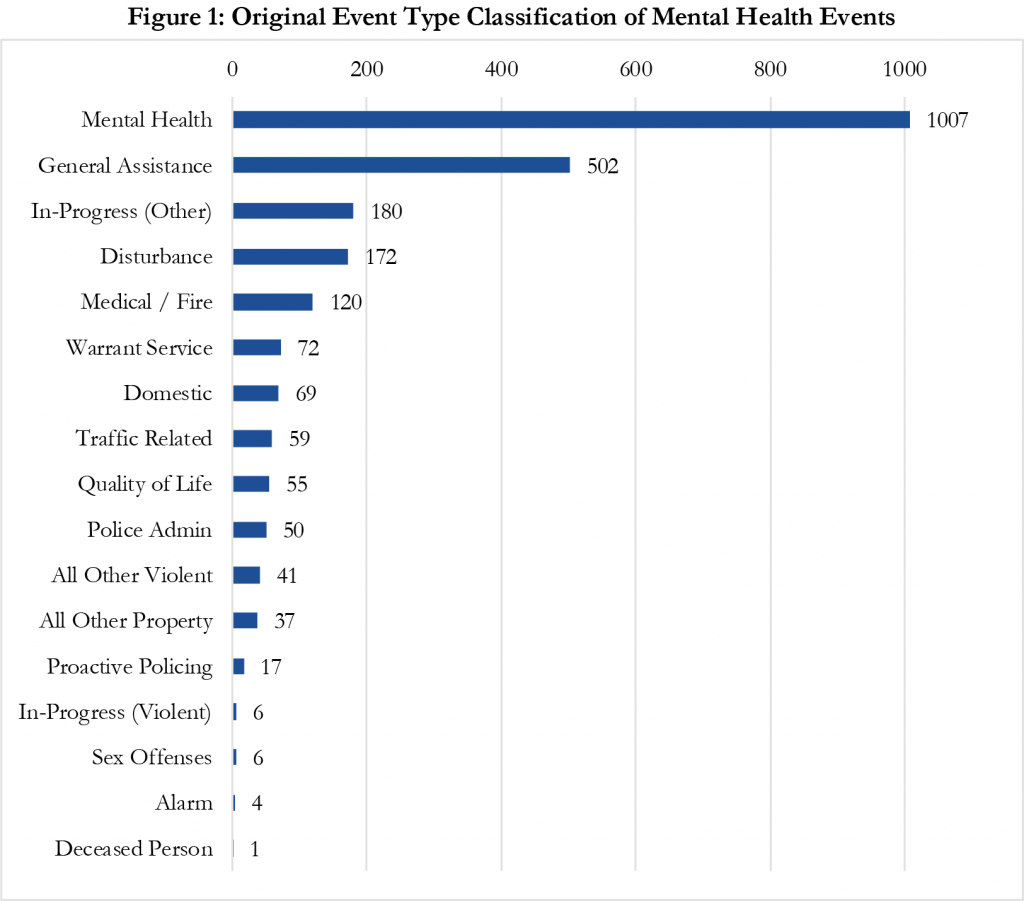

For example, when asked to explore the frequency of mental health events in a cohort city, researchers found that over half of mental health events were misclassified when relying upon the singular measure of event type.11 As shown in Figure 1, events were often dispatched to officers as “general disturbance” or “in-progress (other)”. Further illustrating this issue, some recent research highlighted the wide-ranging inaccuracy of event types. Most agencies record only an initial event type—that is, the event type identified at the creation of the record. However, some agencies also include a final event type—one that is entered by the officer upon conclusion of the event that reflects the officer’s assessment of the situation. Utilizing both initial and final event type provides insight as to how frequently (or infrequently) the initial event type accurately captures the on-the-ground reality. In Tucson, Arizona, an internal police department study found that officers recorded a final event type that was different than the initial event type more than half of the time, indicating that the event type accuracy was less than 50 percent.12 Compare that to a similar analysis that found far greater accuracy in Chandler, Arizona, where an average of 85 percent of 911 calls were accurately classified at dispatch.13 This highlights the need for greater consistency and standardization of practice when recording event types, because the accuracy—and, in turn, the value for policy decisions—varies dramatically across jurisdictions.

Naming and classifying event types are also important for both internal consistency and understanding trends across jurisdictions. In one cohort city, there were spelling and naming differences for the event type depending on the event source, leading to an artificially inflated number of potential event type categories. Not only are duplicates and syntactical differences important to understand so that event types are classified the same way internally, but they also serve as a mandate for consistency across sites. While the authors make no assertions about the optimal number of event types, the range of between 93 and 505 designations in the cohort cities (Table 1) demonstrates the high degree of inconsistency in how event types are recorded and defined.

For the Cohort of Cities partnership, researchers mapped all unique event types from the cohort cities onto 18 categories. The “right” number of categories will depend on the specificity required to answer the questions being asked by commanders, the community, and local officials. For example, in other studies, 7 categories were used to explore how police spend their time, 14 categories were used to identify which types of events may fit well with an alternative to police approach, and 24 categories were used when analyzing call management and policing activity.14 Tucson Police Department’s public dashboard includes two levels of categorization: a broad level with 10 categories, and a specific level with 54 categories.15

What are the outcomes of police events?

Understanding how police events end (i.e., are “closed” or “cleared”) is an important factor for communities and departments to understand. The outcome, measured as the event disposition, may highlight trends such as the prevalence of arrests and noncustodial police actions or even outcomes such as mental health or substance use support.

Like event type, there is significant variability in how agencies record event disposition. Furthermore, dispositions are often affected by department practice and technological requirements; for example, needing to record a particular disposition to generate an associated incident report. One of the cohort cities provides a good example of the potential for uncertainty. The city’s internal data procedures resulted in nearly every event being classified with the event disposition of “closure by arrest.” When over half of the traffic-related incidents showed as ending in arrest, this was a red flag that the data were not communicating what was needed, which is an obstacle to event analysis more generally. Deciphering the meaning of an agency’s CAD values often requires substantive knowledge of the field and the agency, and ambiguities are not always as obvious as the apparent mass arrest of motorists. Anyone analyzing policing event data—either internally or by research partners—should be mindful of the differences in what the data are saying and what the officers are actually doing.

Variability in the use of event dispositions is apparent across the Cohort of Cities and is an important thing to consider when standardizing measurement. RTI and the cohort cities developed eight disposition categories to standardize the data. While the data clearly show that nearly 70 percent of events are either resolved without a report or closed investigations, agency measurement differences make comparison across jurisdictions difficult. Within one cohort city, the police department relied heavily on “resolved without report,” closing 69 percent of its events this way while underutilizing “closed investigation.” Conversely, in another cohort city, the police department closed 57 percent of its events as “closed investigation” and rarely utilized “resolved without report.” Variability in how different agencies conclude their events should serve as a warning and demand for informed understanding of what these values represent before simply collapsing similarly named categories across agencies. Extensive internal awareness of these classifications is necessary for both inter- and intra-agency understanding of police event data.

Lessons Learned

The measurement variability of event source, type, and disposition previously described can be attributed to operational differences, CAD structures, data management capacity, and agencies’ priorities. The extensive differences in measurement between these seven cities, and agencies generally, demonstrate the need for standardization of police event data. This is essential to understanding internal agency data, and, ultimately, for providing a framework to compare trends across communities. As it stands now, the merging of any two police event data sources across agencies yields a complicated tangle of data—only through standardization can more meaningful and intuitive interpretations of these data proliferate.

Motivated by wanting to compare police event activity across the cohort cities, RTI’s collaborative process with the seven cohort cities produced several lessons learned as they relate to police event data that may be helpful to others engaging in this work.

- Develop a strict and consistent definition of the universe of events to include in the analysis—this is important as it ultimately affects all other analyses. Should police events that are cancelled or diverted to another agency be included in the analysis? How should researchers handle duplicate or test events in the CAD system? The answer may vary depending on the questions being asked, but understanding exactly what is and is not included is essential.

- Jurisdictions should seek to standardize and streamline their event type and disposition codes. For example, in one cohort city, 12 unique event types to describe robbery, 20 unique event types to describe larceny, and 20 unique event types to describe alarms are probably unnecessary. Further illustrating the complexity (in the same cohort city), half of the event type codes accounted for only 1 percent of all events. Event dispositions share a similar challenge: 7 unique dispositions to describe a verbal warning or 28 unique dispositions to describe a canceled call are probably also unnecessary. Aside from severely complicating analysis, the level of complexity present may create additional challenges for officers when responding to ambiguous event types or selecting ambiguous event dispositions.

- Input from local/institutional staff is necessary to ensure a complete understanding of the data. Agencies often develop ad hoc event types for particular use cases (e.g., targeted enforcement in a given neighborhood). To an officer at that agency, the type may be obvious. However, to an outside researcher, opportunities for misinterpretation abound. For example, in one cohort city, officer-initiated events appeared to decrease dramatically midway through the study period. To an outside observer, the data seemed to show a policy shift away from proactive policing. However, the cause of the apparent decline was due to a technical change made in the CAD system that impacted how the data were structured—the result of which was realized only through researchers’ analysis. Researcher-practitioner partnerships support accurate interpretation of the complexity and nuances of police event data.

- Agencies should seek to understand how their internal data changes over time, rather than the more typical cross-sectional snapshots. Changes to event data structures, as policies and priorities shift, may often reveal themselves in unexpected ways (e.g., the decline of proactive policing in the previous paragraph). Internal checks to ensure continued and consistent retrieval and interpretation of the data are important. While researchers must rely on practitioners to fully understand the nuances of the data, practitioners may also benefit from research-led clarifications and trend analyses.

Getting to the “Next Frontier”

A first step jurisdictions should take to improve their understanding of police activity and community needs follows a basic but important mantra— “know your data.” A full accounting of how police events are recorded, including the range of values and how frequently they are used can quickly highlight areas for improvement opportunities. Local analysis or IT staff, as well as outside researchers, can be helpful in organizing and analyzing the data. Though standardization across jurisdictions may still seem out of reach, the more researcher-practitioner partnerships are developed and the more efforts in this space are highlighted, the more that congruence and best practices can be developed.

RTI is actively working to support these broader efforts to explore and analyze police event data. Multiple concurrent projects are building upon the lessons learned from the Cohort of Cities to analyze police event data and address a range of questions from alternatives to police responses to policing practices in immigrant communities. But, to avoid the laborious process of standardizing thousands of unique data values across organizations, RTI is also developing an automated tool, the Police CAD Autocoder (PCA), to create efficiencies in the analytical process. The tool, which will be publicly available on the Internet and free to use, uses machine learning and natural language processing to automatically assign the range of unique values into different levels of categorization (e.g., broad versus specific). As data from jurisdictions continues to be ingested by the tool, the accuracy and refinement of the automatic assignments will continue to increase. The PCA will not replace the need for institutional knowledge of the data values, but, ultimately, with time and a move toward standardization, the widespread ability to understand police activity and community needs will be within reach.

Notes:

1Jeff Asher, “Numbers Racket: There’s Great Crime Data for Nearly Every City in the United States. Why Is Nobody Using It?” Slate, March 15, 2016.

2Jeff Asher and Ben Horwitz, “How Do Police Actually Spend Their Time?,” TheUpshot, The New York Times, June 19, 2020; Rebecca Neusteter et al., Understanding Police Enforcement: A Multicity 911 Analysis (Vera Institute, 2020); Cynthia Lum, Christopher S. Koper, and Xiaoyun Wu, “Can We Really Defund the Police? A Nine-Agency Study of Police Response to Calls for Service,” Police Quarterly 25, no. 3 (September 2022): 255–80.

3 Jack R. Greene, “Measuring and Understanding What the Police Do,” presentation (CEPOL Conference, Lisbon, Portugal, October 8, 2015).

4This project was supported by Arnold Ventures.

5Neusteter et al., Understanding Police Enforcement; Two Sigma Data Clinic, Abdul Rad, and Frankie Wunschel, Making 911 Accessible: A Guide to 911 Open-Datasets (Vera Institute, 2020).

6Jeff Asher, “Numbers Racket”; Jeff Asher and Ben Horwitz, “How Do Police Actually Spend Their Time?,” TheUpshot, The New York Times, June 19, 2020; AH Datalytics, Assessment of Austin Police Department Calls for Service (2020).

7Lum, Koper, and Wu, “Can We Really Defund the Police?”

8The National Emergency Number Association (NENA) and the Association of Public-Safety Communications Officials (APCO) have developed standards, though adoption and use appear limited.

9 Tiffany Chu and Mark Lubniewski, “Something Happened on the Way to the Call: Challenges in Predicting Call Outcomes Based on Initial Call Type,” presentation (International Association of Crime Analysts 2021 Training Conference, Las Vegas, Nevada, August 25, 2021).

10 Rebecca Neusteter, “Understanding Law Enforcement Response: An Examination of 911 Calls for Service,” PowerPoint slides, 3–25, from “Taking the Call: What 911 Data Does and Does Not Tell Us About Divertible Calls,” presentation (Taking the Call, virtual conference, October 20, 2021).

11 Renèe J. Mitchell, Sean Wire, and Alan Balog, “The ‘Criminalization’ of the Cop: How Incremental, Systematic Flaws Lead to Misunderstanding Police Calls for Service Involving Persons with Mental Illness,” Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice, April 11, 2022.

12 Tiffany Chu and Mark Lubniewski, Calls for Service: Understanding When Police are Needed (2020); Kevin Hall, K. (2021, October 20). “An Analysis of 911 Calls for Service in Tucson: Can We Accurately Determine Appropriate Calls for Alternative Responses?,” PowerPoint slides, 26–43, from “Taking the Call: What 911 Data Does and Does Not Tell Us About Divertible Calls,” presentation (Taking the Call, virtual conference, October 20, 2021).

13 Rylan Simpson and Carlena Orosco, “Re-assessing Measurement Error in Police Calls for Service: Classification of Events by Dispatchers and Officers,” PLoS One 16, no. 12 (December 2021): e0260365.

14Asher and Horwitz, “How Do Police Actually Spend Their Time?”; Lum, Koper, and Wu, “Can We Really Defund the Police?”; Neusteter et al., Understanding Police Enforcement.

15 Tucson Police Data & Analysis, “Police Activity,” dashboard.

Please cite as

Jacob Cramer and Sean Wire, “The Next Frontier: Using Police Activity Data to Expand Our Understanding of Community Needs,” Police Chief Online, August 17, 2022.