2020 highlighted cracks in the social foundation of communities across the world. The compounding stress caused by COVID-19 and economic uncertainty illuminated existing inequities, and the death of George Floyd sparked a full-scale excavation to expose systemic challenges in the United States that have been destabilizing community relations for years.

These situations were further exacerbated by modern communication and the speed of digital dialogue. The impact of a single event is no longer confined to a geographic location; it has a real-time effect on people around the globe who identify with the affected individual or group. The cataclysm of several large events in the last year brought law enforcement and community relations to an unprecedented low point.

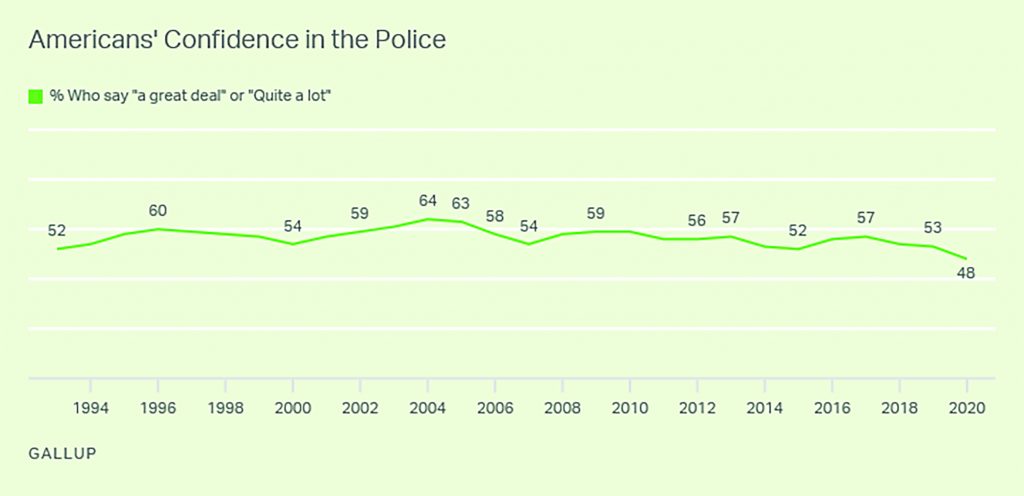

An August 2020 Gallup poll revealed a five-point drop in public confidence in law enforcement, bringing it to 48 percent, the lowest rating in 27 years. Driving the point even further home was the fact that this decline came during a time when other public institutions actually saw an upward trend in public confidence.1

|

From survey instruments to civil unrest, the message is consistent and clear: community relations are no longer just a “nice to have” option for law enforcement agencies; an investment in strategic, specific, and ongoing communication is now a necessity, with very real impacts on public safety, officer safety, and the future of the policing profession.

In order to successfully build and maintain trust, law enforcement agencies must take a two-fold approach: (1) continue engaging with the general population through mainstream methods and (2) dedicate focused resources to identify and address the obstacles that fuel distrust and inhibit positive relationships, especially within minority and underserved populations.

A Two-Fold Approach

Law enforcement agencies have been called to meet numerous, and sometimes conflicting, demands at the national, state, and local levels. Calls for change have ranged from broad and thematic (e.g., improve community relations, build trust, create more equitable and inclusive environments, reimagine policing) to more specific and literal (e.g., revise use-of-force policies, publish policing data through an equity lens, remove officers from mental health calls, defund public safety budgets, abolish police departments).

As a profession defined by structure and operations policing may naturally gravitate toward the tangible elements. However, while data and policy provide a necessary baseline to begin discussions, these tools alone cannot effectively address the emotional elements of inequity or injustice.

Trust comes in two forms: cognitive and affective. Cognitive trust is logical, factual, and based on evidence. Affective trust is the emotionally based sense of confidence in another following an interaction, and it can be described as the “gut feeling” about an interaction.2

In order to repair the fractured public confidence in law enforcement, police leaders must identify social and emotional threats and develop solutions to support both forms of trust. Communities are safer when all residents feel comfortable working with the police. In the absence of public confidence, people may avoid reporting suspicious behavior, illegal activity may be overlooked, and victims may hesitate to seek services. Conversely, a collaborative environment allows officers to work with residents to solve low-level problems before they become chronic issues, reduce victimization, and empower community members to take an active role in preventing and reporting crime.

Agencies and communities will need to invest time and energy to identify common values, define goals and obstacles, and build bridges. Mutual understanding will ultimately shore up the bedrock of community trust, but it takes time, open dialogue, and regular effort to sustain.

Community engagement is a commonly accepted part of policing in the 21st century. However, many agencies still rely on one-size-fits-all, reactive approaches rather than employing a strategic planning model with defined audiences, goals, and metrics. Geography-based outreach typically centers around neighborhoods and issues unique to a particular area. While that approach still has merit as part of community policing principles, adding identity-based outreach will allow agencies to expand efforts to more effectively resolve issues inhibiting public trust. Social and cultural identity shape a person’s sense of self, purpose, and metaphorical place in the world. A one-note engagement strategy that doesn’t acknowledge varied identities misses the nuanced obstacles and opportunities that a multifaceted focus can bring to light.

In order to successfully build and sustainably reinforce community trust, especially among minority and historically underserved populations, law enforcement agencies must create ongoing opportunities to engage authentically with different parts of their communities. Connecting with a respected leader and influencer within local populations can provide a starting point for such outreach efforts. These individuals have earned the trust and confidence of their peers and are well-positioned to help facilitate meaningful interactions that benefit their community. Without the valuable perspectives from members of these groups, agencies may waste resources on well-intentioned but ineffective outreach efforts. Knowing where community members get their information, their preferred communication methods, and their primary areas of concern related to the police can help guide efforts immensely. Trusted representatives may also provide feedback from community members who lack the trust or confidence to share their concerns directly.

Grand Junction, Colorado, Police Chief Doug Shoemaker and Colorado Mesa University Football Coach Tremaine Jackson forged a meaningful connection in 2020 as students and police alike were grappling with the implications of a troubled nation. Together, the chief and coach have laid the groundwork for ongoing dialogue, active listening, and mutual understanding between student athletes, community members, and local police officers. Through this connection, they have been able to identify common threads and shared leadership values that are relevant on the field, in a team environment, and in policing.

Another focused community partnership began in Fort Collins, Colorado, after a group of residents brought forth concerns from the local immigrant community in 2017. The city council directed internal staff to convene with a diverse community stakeholder group to explore the issue. The group met over a four-month period to identify barriers to inclusion and opportunities to improve various city services. Together, they developed recommendations for changes and clarifications to policy, programming, and practices that could enhance a sense of inclusion across the city. Fort Collins Police Services representatives took part in this process and, as a result, developed a better understanding of challenges within the local immigrant community and formed positive connections with local leaders.

Fort Collins police ultimately partnered with a local nonprofit organization to better connect with Spanish-speaking residents, identify and remove barriers to service, and reassure residents that the agency did not proactively enforce or inquire about immigration status. The agency invested in language training and formed a Spanish team that hosts informational and social events known as Cafecitos throughout the year for this community. Through these Cafecitos, community members have helped identify gaps in information accessibility, shared concerns about criminal activity in a local park, and requested presentations about topics like internet safety for teens. The approach has addressed both the cognitive and affective elements of trust by highlighting policy, as well as creating a sense of bonding over stories and fostering authentic interactions.

Fort Collins Police Chief Jeff Swoboda has taken an active part in the community conversations around equity, inclusion, and racial justice, noting,

Building and maintaining a strong relationship with the people we serve is one of the most important elements in policing. As we grow together with our residents, law enforcement agencies must continually reflect and adapt to make sure we’re truly serving all residents with cultural consideration and compassion. Without our community, we fail.3

A Trauma-Informed Approach

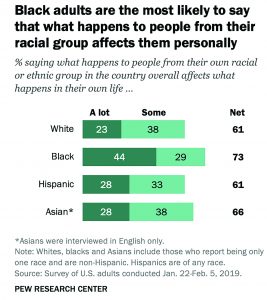

Minority communities have been deeply and personally impacted by graphic images and incidents that involved people of color. A 2019 Pew Research Center study explored the concept of “linked fate.” Research indicated that the majority of adults in the United States feel they are personally affected by things that happen to their own racial or ethnic group.4

|

In addition to this notion, emerging research has also found that exposure to violent events through media or social media can result in vicarious trauma symptoms among viewers.5 Countless people watched the 8-minute, 46-second video capturing the final moments of George Floyd’s life. Widespread coverage about the death of Breonna Taylor in Louisville, Kentucky, and video of the shooting of Jacob Blake in Kenosha, Wisconsin, further ignited the fear, frustration, and mistrust of the police. The death of Ahmaud Arbery at the hands of a white neighbor heightened pain and anger around the topic of racial justice. All of these incidents, as well as images of cities literally burning, played out 24/7 online and on television during a summer when people were confined to their homes due to a pandemic. The long-term emotional impact of this onslaught of stress is yet to be determined, but it will no doubt continue to manifest in communities across the United States.

The 2020 storm left visible and invisible wreckage in its wake. While many agencies have continued or renewed outreach efforts, success will depend on leadership’s emotional intelligence and ability to adapt to shifting community needs.

As law enforcement agencies work to repair and improve relationships, especially with minority and historically underserved populations, leaders must factor in considerations for creating an environment conducive to meaningful interaction. This can be achieved using the six principles of a trauma-informed approach: safety; trustworthiness and transparency; peer support; collaboration and mutuality; empowerment and choice; and sensitivity to cultural, historical, and gender issues.6

Safety: Creating an environment that not only is safe, but also feels safe for all participants requires comprehensive consideration. Elements that may impact a sense of safety may include the following:

-

- Attire—Much like “white coat syndrome,” in which the presence of a doctor induces tension, the presence of uniformed police may increase anxiety among people with negative personal experiences or strong perceptions about the police. This may be a factor that influences attendance or participation, so consider attire options such as plainclothes, branded polos, or soft uniforms if this could be an issue for the intended audience. That being said, alternative clothing might not always be a possibility. Either way, officers can employ emotional intelligence and crisis training skills to recognize and ease anxiety that may manifest in the presence of a uniform.

- Event location—From a psychological standpoint, individuals feel a sense of ownership and safety in their primary territory, recognized in the psychology world as the space controlled by and identified with the person or group who uses it exclusively.7 Hosting events at the police station inherently shifts the balance of power and ownership to law enforcement, which can inhibit a sense of collaboration if the attendees are uncomfortable with or intimidated by police. When planning a location to host events, consider neutral common spaces, or public territories, like a community center or library. Groups with a high level of discomfort may benefit from events hosted in their own primary territories or other familiar locations, such as a local service provider’s office or church meeting space.

- Event advertising—People who fear targeting by outside entities may hesitate to attend events that are openly advertised. Consider working with representatives from these niche communities to extend invitations by word of mouth or advertising via channels run by their affiliated organizations.

- Event photos or recordings—Be mindful of individuals who may have concerns about their personal identities or images being shared publicly. While promoting the agency’s efforts to the broader community is important, doing it at the expense of an individual’s trust can hinder long-term success. This can be easily achieved by simply asking permission before taking photos. Likewise, recording discussions may inhibit vulnerability, so consider alternative methods of capturing important points or sharing takeaways with those who could not attend.

Trustworthiness & Transparency: Trust is built from four components: benevolence, integrity, competence, and predictability.8 Developing these requires law enforcement agencies to demonstrate that their employees care about the well-being of community members, operate ethically and fulfill commitments, have the skills and ability to do their job, and act consistently over time. Due to the complex nature of the policing profession, proactive transparency is necessary in order to give people access to information that supports these components. A failure to provide context will result in public opinion being based solely on personal experience (which is limited for the average person), hearsay, social media, and mainstream media.

For many years, the Mountain View, California, Police Department has taken a highly proactive approach to transparency. As uncertainty and distrust grew around the United States in 2020, the agency launched a page on its website to host leadership statements about major events, a response to national initiatives like the 8 Can’t Wait campaign, use-of-force statistics, and infographics depicting the organization’s policing philosophies and expectations. This information was also shared on social media to enhance visibility.

Peer Support: In the trauma-informed approach, peer support refers to giving individuals who have experienced trauma access to others who have lived through similar situations. In the community engagement model, this may mean planning opportunities for experience sharing. If agencies have staff members who identify in some way with the community group, highlighting this common thread can also create a sense of connection and support.

Collaboration & Mutuality: Defining goals and the scope of authority up front will provide clear expectations, minimize misunderstandings, and allow participants to understand opportunities and limits. When planning outreach efforts, think about ways to invite attendee collaboration. This could mean planning a future event, asking for their help identifying gaps in service, or co-developing programming. While not all decisions can or should be made by committee, finding opportunities to take mutually beneficial action can increase the sense of trust and partnership within community groups.

Empowerment & Choice: Traumatic experiences can rob individuals of their sense of personal power. By approaching community engagement with a mindset of empowering residents to work as partners who choose to take action, law enforcement agencies can improve relationships, leverage community skills, and amplify community safety efforts. Meaningful action can take the form of giving residents an opportunity to review and make recommendations on programs. Inviting groups to share their experiences and help inform improved approaches to communication can also develop a sense of empowered purpose.

Cultural, Historical, & Gender Issues: The heart of the disconnect between the police and minority and marginalized groups stems from this space. Acknowledging the inherent or historic challenges faced by individuals from a specific culture, gender, or other identity-based group is necessary in order to have contextual discussions about trust.

Summary

Policing stands on the cusp of a new era. Navigating the impacts of a global pandemic, a defining national shift in the conversation around racial justice, and rapidly evolving digital communication culture can be an overwhelming endeavor. Agencies will succeed by focusing primarily on the specific needs and opportunities within their local communities. This will require ongoing strategic communication, emotional intelligence, resource and personnel investment, and a unified resolve to continuously understand and help resolve obstacles to trust in all segments of the population.

Right or wrong, the reality is that the police no longer have the luxury of assumed trust. Public confidence must be earned again and again. Building strong relationships with diverse communities will position agencies to engage in meaningful local conversations when issues do arise. Policing is built on an enduring spirit of service, honor, and integrity. The road ahead is filled with opportunities to let those values illuminate the dark and broken corners of communities. The work starts at home, and every agency holds the individual responsibility of identifying barriers and building bridges. By listening, collaborating, and connecting, especially with minority and marginalized groups, police agencies can restore confidence and increase safety across their communities. d

Notes:

1Megan Brenan, “Amid Pandemic, Confidence in Key U.S. Institutions Surges,” Gallup, August 12, 2020.

2Marianna Pogosyan, “Who Do You Trust?” Psychology Today, June 5, 2017.

3Jeff Swoboda (police chief, Fort Collins Police Services, Colorado), in discussion with the author, December 30, 2020.

4 Kiana Cox, “Most U.S. Adults Feel What Happens to Their Own Racial or Ethnic Group Affects Them Personally,” Pew Research Center, July 11, 2019.

5Danielle Render Turmaud, “Watching the News Can Be Traumatizing,” Psychology Today, January 14, 2020.

6Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), SAMHSA’s Concept of Trauma and Guidance for a Trauma-Informed Approach (Rockville, MD: SAMHA, 2014).

7APA Dictionary of Psychology s.v. primary territory.

8D. Harrison Mcknight and Norman L. Chervany, “Trust and Distrust Definitions: One Bite at a Time,” in Trust in Cyber-Societies: Integrating the Human and Artificial Perspectives, ed. Rino Falcone, Munindar Singh, and Yao-Hua Tan (Berlin, Germany: Springer, 2001), 31.

Please cite as

Kate Kimble, “The Path to Trust: Engaging Underserved Communities & Rebuilding Public Confidence,” Police Chief Online, March 10, 2021.