Leadership is solving problems. The day soldiers stop bringing you their problems is the day you have stopped leading them. They have either lost confidence that you can help or concluded you do not care. Either case is a failure of leadership. — Colin Powell

The role of supportive leadership in mitigating risks of stressors on the mental health and well-being of personnel has been researched and discussed from various perspectives for years, and, recently, in 2011–2012, two professors from Carleton University in Ottawa, Ontario, investigated the cost to police services of their organizational, operational, and human resources practices. This study, titled the National Work-Life and Employee Well-being Study, engaged 25 police services across Canada, surveying a total of 4,500 sworn and 2,500 civilian personnel. The distribution of respondents reflected the distribution of rank across Canada—two-thirds of the respondents were constables, 16 percent were sergeants, 6 percent were staff sergeants, and 15 percent served in command positions.¹

In the resulting report by Linda Duxbury and Christopher Higgins, the role of leadership was identified as a key contributor to the overall functional efficiency of the police services. One of the most interesting findings was how much the reduced stress experienced by personnel who reported to supportive leaders positively affected the bottom line in multiple ways. Key findings of the study included the following:

- Supportive leadership is strongly associated with the financial health of the organization as well as its ability to recruit and retain talent. It is also strongly associated with employee well-being [stress, depression], work-life conflict, and the perception that one is overloaded and crunched for time at work and at home.

- As a whole, two thirds (65 percent) of the respondents report high job satisfaction, while only 5 percent are dissatisfied with their jobs, and 30 percent are neutral.

- Just over half (52 percent) of the respondents reported working for supportive managers, but almost one in five (19 percent) work for non-supportive managers, and 29 percent work for a “mixed” manager.

- Of those who work for non-supportive managers, 68 percent reported high stress levels. That figure drops to 55 percent of those who report to mixed-support managers, and only 40 percent of those who deal with supportive managers reported high stress.

- The results regarding depression indicate that 46 percent of those who work for non-supportive managers reported high levels of depressed mood, with 34 percent of those who work for mixed-support managers reporting high levels of depressed moods, and only 21 percent of those reporting to supportive managers reported high levels of depressed mood.²

The research goes on to identify characteristics of supportive leaders. It is clear from the study’s results that overall job competence, emotional intelligence, strong communication, and situational leadership skills play an important role in whether a leader is considered to be supportive.

In addition, despite the difficult and potentially traumatic work often faced by police officers in their day-to-day responsibilities, Duxbury and Higgins’ research identifies the most distressing experiences for law enforcement professionals, both sworn and unsworn, as arising from organizational and personal issues, not the trauma of assisting others through operational responsibilities.3 Their findings support the work done by Patricia Fisher in 2001, which suggested that a law enforcement leader plays a significant role as both a person who successfully models effective stress management strategies (resilient role model) and as a significant stressor for those who work with or for the leader when he or she behaves in non-supportive ways.4

The Duxbury and Higgins report does not stand alone in its results. In October 2012, the Ombudsman for Ontario, Canada, released a report, In the Line of Duty.5 The investigators undertook a critical analysis of the mental health and wellness supports available for police service personnel in the province. The report focused primarily on one police service, but it was clear there were implications for all police services in the province of Ontario. Many recommendations highlighted the need for supportive leaders to pave the way to good mental health by getting to know their staff, reducing the stigma related to mental illness, making it easier for staff to come forward for assistance, and modeling resilience through proactive engagement. Additionally, there was a renewed awareness of the value early intervention and prevention can bring to the challenges faced by police personnel as they encounter the many organizational, operational, and personal challenges a life in law enforcement can bring.

Leadership, Resilience, and Mental Readiness

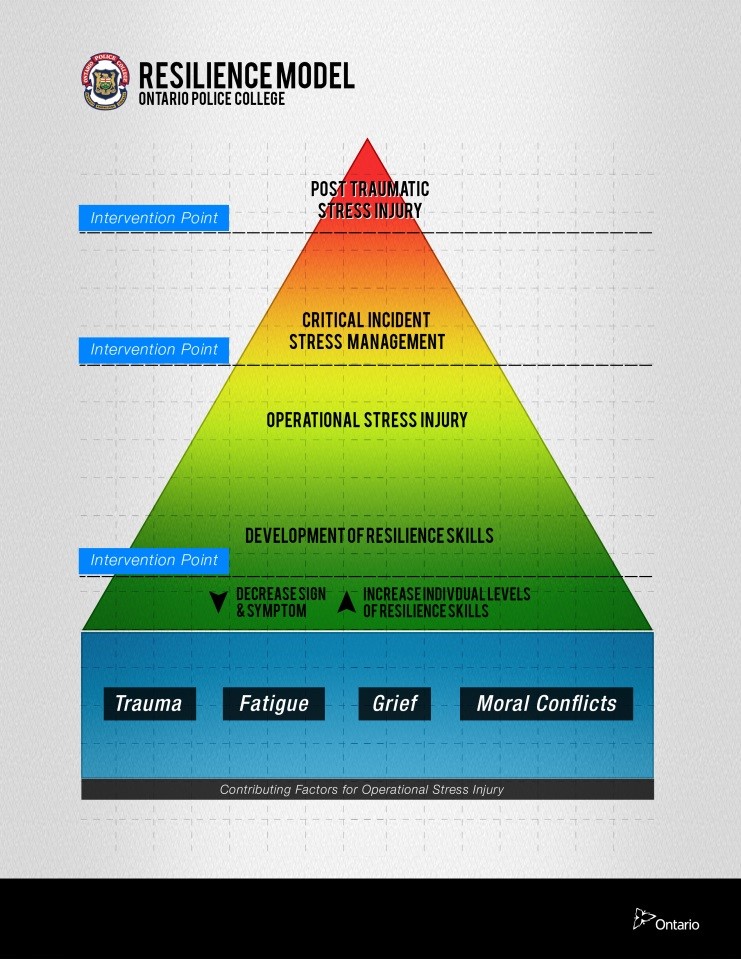

Figure 1, prepared by the Ontario Police College (OPC), visualizes the complexities surrounding the impacts of work and life stressors on an individual’s psychological health and well-being. The important elements are the available intervention points, which provide opportunities to apply resilience skills, supportive leadership, and the concurrent reduction of stigma and barriers to care to decrease symptoms of distress. If treatment and supports for operational stress injuries are successfully managed at the intervention points, it is hoped that fewer personnel will reach the threshold for a post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) diagnosis. It is important to appreciate how research on PTSD intervention strategies are improving the well-being and quality of life for those managing these challenges, while still focusing attention on providing education and support for mental health issues that are distinct from PTSD. To this end, the OPC is working with the Mental Health Commission of Canada (MHCC) and the Department of National Defence (DND) to bring the evidence-based Road to Mental Readiness (R2MR) program to police services in Ontario and beyond. This collaboration is supported by the Ontario Association of Chiefs of Police (OACP) and has several specific objectives.

Road to Mental Readiness

There are two police-specific MHCC R2MR programs currently offered at OPC. For front-line personnel, there is a four-hour Primary Training program, and for organizational leaders, there is an eight-hour Leadership Training program. Both training sessions focus on achieving the common goals of decreasing the stigma around mental health issues and barriers to care; increasing resilience skill development; and creating a common language of support and education using the Mental Health Continuum Model. The Leadership Training program also provides specific information about suicide prevention and the responsibility of leaders to create an environment that is supportive and engaging for their staff by monitoring the impact of cumulative stressors and providing appropriate intervention strategies at the conclusion of identified critical events.

Key Role of Leadership in Mental Health Continuum

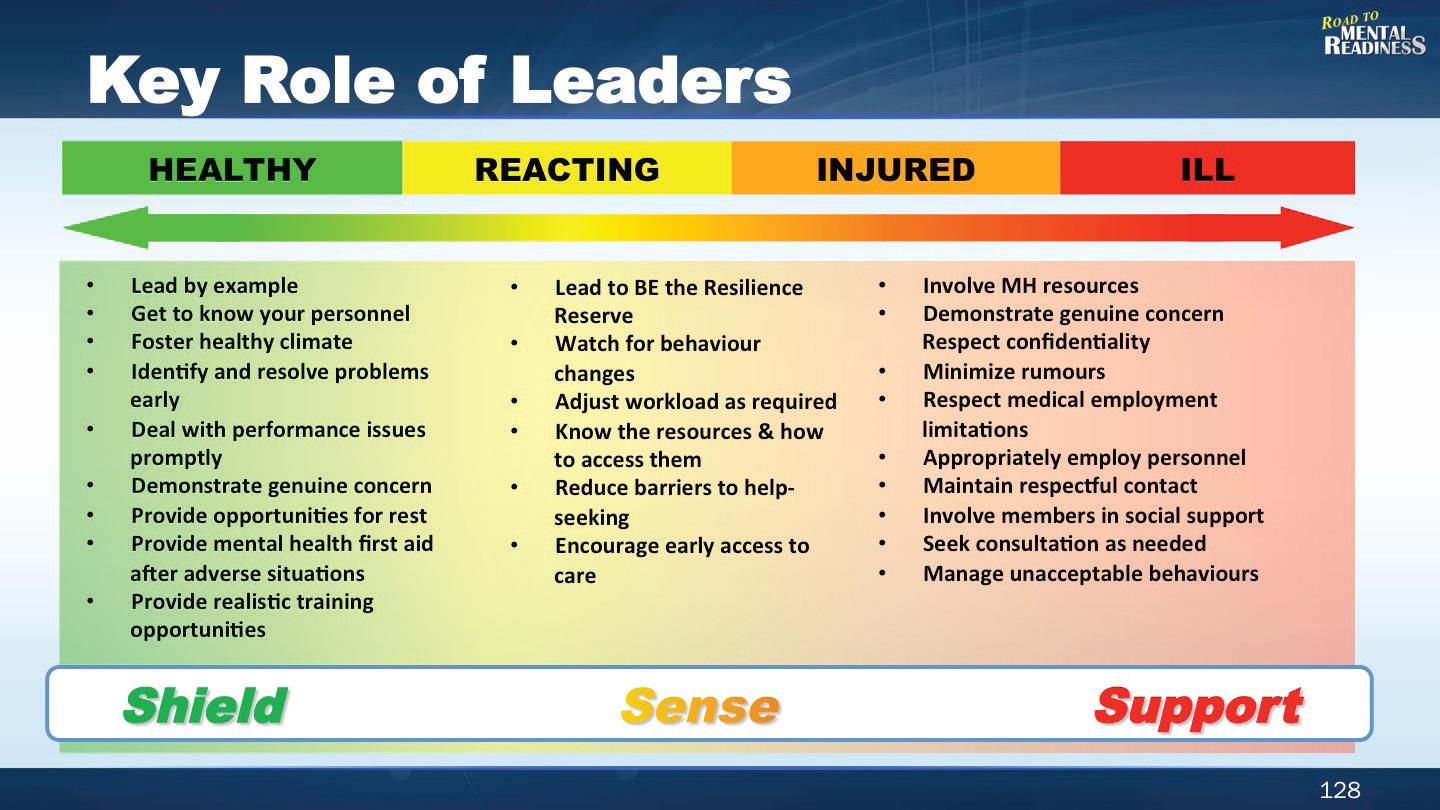

The previously mentioned research by Duxbury and Higgins supports the belief that when police leaders focus on the health and overall wellness of their personnel, those personnel are then better positioned to serve the community and each other. Figure 2 identifies various actions that can be facilitated by police supervisors and health care providers to support their personnel. Through the processes of shielding, sensing, and supporting staff in diverse circumstances along the Mental Health Continuum Model, supportive leadership plays a significant role in maintaining the mental health of police service personnel and assisting those with issues to remain at or return to work quickly.

This perspective on the importance of supportive leadership is reflected in international reports like the May 2015 Final Report of the President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing, which, in Pillar Six, recognized

The wellness and safety of law enforcement officers is critical not only to themselves, their colleagues, and their agencies but also to public safety.…

Officers who are mentally or physically incapacitated cannot serve their communities adequately and can be a danger to the people they serve, to their fellow officers, and to themselves.6

The Mental Health Continuum Model, Pillar Six of the task force report, and the research of Duxbury and Higgins clarify the points of overlap where the role of effective professional law enforcement leadership supports the delivery of civic responsibilities while also caring for the overall well-being of any agency’s personnel. Those police leaders studying and living the operational responsibilities of rank are keenly aware that being a leader increases one’s personal stress, as well as making one a stressor for those working with and for the individual. To what extent a leader is a stressor for others depends, of course, on the leader’s level of support and respect for those he or she leads. As pointed out in the President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing report,

An agency work environment in which officers do not feel they are respected, supported, or treated fairly is one of the most common sources of stress. And research indicates that officers who feel respected by their supervisors are more likely to accept and voluntarily comply with departmental policies. This transformation should also overturn the tradition of silence on psychological problems, encouraging officers to seek help without concern about negative consequences.7

Need for Mental Health Support in Law Enforcement

Are mental health and wellness programs necessary in law enforcement agencies? Based on information in a recently published article in Rotman Management,

mental illness has become a leading global health concern… [Currently,] depression is the health condition with the largest individual-level effect on work performance. Estimates of the direct and indirect costs range from $36 to $51 billion.8

The article goes on to point out the role of leadership in employee mental health:

Managerial attitudes and skills in relation to mental health are pivotal to the effectiveness of a cooperative nexus between the employee, their health professional, and the psycho-social work environment.9

Reports from the MHCC reflect the same data, reinforcing the significance of managing mental health in the public forum and the constituency of law enforcement agencies, which mirror general Canadian society. The MHCC statistics suggest the following:

- One in five Canadians are affected annually by mood disorders, anxiety disorders, schizophrenia, attention deficit/hyperactive disorders, conduct disorders, oppositional defiant disorders, substance abuse disorders or dementia.10

- Only about 1 in 3 people who experience a mental health problem or illness report that they have sought and received services and treatment.11

This means that, for various reasons, 2 out of 3 people experiencing a mental health issue or illness are not getting the support they need to deal with their illness. These individuals are colleagues, friends, and family members who are trying to function at work and at home while managing a substantial health issue. This is a worldwide issue currently under consideration by the World Health Organization (WHO).

The information in the WHO Action Plan correlates with the research conducted by Linda Duxbury and Christopher Higgins and reinforces the connection between good mental health, productivity, and supportive leadership; therefore, one of the four primary objectives identified in the WHO Mental Health Action Plan is “to strengthen effective leadership and governance for mental health.”12

The ability of supportive leaders to model resilient behaviour through their own consistent displays of professional practice, by being aware of their peers and colleagues so they can provide early intervention when challenges grow, and knowing what resources are available when intervention is required are critical to an organization’s success. Healthy police leaders increase the ability to manage conflicting responsibilities and assist police service personnel to achieve a feeling of contentment and satisfaction in their personal and professional lives. Leaders can model these healthier habits for their colleagues, peers, and families.

Conclusion

During a leadership training event in Florida, several years ago, a chief of police shared with his colleagues a lesson learned about being the “thermostat” for the members of his police service. He indicated it was his responsibility to maintain a steady temperature for the members of the organization. At those times when staff members may be like a thermometer, running hot or cold depending on the situation they are reacting to, as the thermostat his role was to restore the equilibrium (“temperature”) by assisting them in managing their stress and being resilient. This allows officers to better serve themselves, their colleagues, family, and community.

The MHCC R2MR training being offered to police service personnel throughout Canada can help leaders understand their role as a “thermostat” and resilience builder. The research discussed herein highlights the need for supportive leaders to maintain the health and well-being of their individual personnel and the impact on the entire organization. By continuing to develop supportive leaders within all ranks of a police service, both sworn and unsworn members will have a better chance of enjoying the return on investment reflected in a better quality of life for all stakeholders in the organization and the communities they serve.

Instructor Irene Barath of the Ontario Police College is the team leader for the Leadership Development Unit and is also the resilience and wellness training coordinator. She served for 15 years as a sworn officer with a large police service prior to becoming a full-time trainer at OPC for the past 18 years. Irene has delivered leadership training both nationally and internationally, including a Leadership Fellowship and Visiting Scholar Program with the FBI National Academy in Virginia. She is also a master trainer for the MHCC Road to Mental Readiness Program.

Notes:

1Linda Duxbury and Christopher Higgins, Caring for and about Those Who Serve: Work-Life Conflict and Employee Well-being Within Canada’s Police Departments (Ottawa, ON: Carleton University, March 2012), 1, http://sprott.carleton.ca/wp-content/files/Duxbury-Higgins-Police2012_fullreport.pdf (accessed November 15, 2016).

2Ibid., Figure 63b: Employee Health, 78.

3Ibid.

4Patricia M. Fisher, The Manager’s Guide to Stress, Burnout and Trauma in Law Enforcement (Victoria, BC: Spectrum Press, 2001).

5André Martin, In the Line of Duty (October 2012), www.ombudsman.on.ca (accessed November 15, 2016).

6The President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing, Final Report of The President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing (Washington, D.C.: Office of Community Oriented Policing Services, 2015), 61, 63, https://cops.usdoj.gov/pdf/taskforce/taskforce_finalreport.pdf (accessed November 15, 2016).

7Ibid., 62.

8Angela Martin, Megan Woods, and Sarah Dawkins, “Managing Mental Health in the Workplace,” Rotman Management, The Health Issue (Winter 2016): 75.

9Ibid.

10Paul Smetanin et al., The Life and Economic Impact of Major Mental Illnesses in Canada: 2011 to 2041 (Mental Health Commission of Canada, December 2011), 6, http://www.mentalhealthcommission.ca/sites/default/files/MHCC_Report_Base_Case_FINAL_ENG_0_0.pdf (accessed November 15, 2016).

11Statistics Canada, “Canadian Community Health Survey: Mental Health and Well-being,” The Daily, news release, September 3, 2013, www.statcan.gc.ca/daily-quotidien/030903/dq030903a-eng.htm (accessed November 15, 2015).

12World Health Organization, Mental Health Action Plan 2013–2020 (2013), 10, 11, 20, and 23, http://www.who.int/mental_health/publications/action_plan/en (accessed November 15, 2016).

Please cite as

Irene Barath, “The Role of Supportive Leadership Practices in Maintaining the Health and Wellness of Law Enforcement Personnel and Organizations,” Police Chief Online, Nov 16, 2016.