At many police departments and law enforcement agencies, the public information office has historically played a supportive but minimal role when it comes to organizational strategy. The function of the communications team was largely viewed as reactive and limited in scope, with the primary purposes of informing stakeholders about noteworthy calls for service, addressing critical incidents, and providing notice of general law enforcement initiatives within a particular jurisdiction.

Organizational perception, transparency, trust building, communications planning, and counsel were all essentially nonexistent, as these offices were commonly staffed with either low-ranking officers without formal training in communication or civilians with little to no policing background.

Sworn officers within the communications office had few supporters among their peers and supervisors. Civilians arrived with communications proficiency, but were left without a voice when it came to organizational decision making. Additionally, public information offices were buried within bureaus and low-priority units, relying on an indirect reporting structure that rarely interacted with the chief executive.

Because the public information office was not operationally aligned, communications team members were rarely invited to executive-level meetings. This stood in the way of their ability to gather information in real-time that could be later used to develop strategic messaging. These operational challenges left communication directors unable to provide strategic direction due to a lack of familiarity. Communications directors also lacked decision-making confidence within a sworn police culture. This was coupled with a lack of organizational posture (or rank) within the organization. All these obstacles stood in the way of out-of-the-box strategic approaches that cut across the traditional, paramilitary chain of command.

In recent years, many agency heads have realized that this approach fell short of the end goal—to foster prolific communication that shapes public perception and ultimately builds trust. Agencies are increasingly capitalizing on a new way of thinking when it comes to strategic messaging—some have even created their own newsrooms in an effort to tell stories that tie back to their goals and produce engaging multimedia content in a direct-to-consumer approach.

Shift in Communications Strategy

Many major city police departments have been slowly but steadily moving toward this new model by developing a public information office that is operationally aligned and integrated into the decision-making process. For example, Richard Esposito serves as the New York Police Department’s (NYPD’s) executive-level deputy commissioner of public information. His role includes coordinating communication with local and national media outlets as well as being responsible for reputational management. Esposito also advises NYPD Police Commissioner Dermot Shea and other senior leaders, whom he serves as a direct report. Other agencies have followed suit, driven in part by the public’s demand for a steady stream of social media content. The end result is a strategic communication office and an assortment of community engagement vehicles that are a direct reflection of the department’s priorities.

Having empowered and highly trained communications experts on hand with a direct-reporting structure to the chief executive plays a key role in this strategy. This positioning must be followed by inviting communications team members to a seat at the table throughout the decision-making process. Witnessing the decision-making process firsthand empowers communication staff to provide the best context for how these decisions are made; they can effectively share information with reporters and the public. Being keyed into the process also gives public information officers an awareness of who within the department is making important decisions. Thus, communication teams can properly staff and prepare top-level executives for media interviews as well as community town halls and question-and-answer sessions. Once armed with this information, communications teams then need to be trusted to build both internal and external messaging with an ever-present eye on the department’s reputation, as well as permission to develop long-term strategic goals. Finally, communications teams need to be trusted with how and when to effectively share news with various stakeholders.

This level of trust, insight, and knowledge is vital, as communications teams build messaging around critical incidents as well as major initiatives. It’s also important to remember that these same communication teams must think ahead with forward-looking messaging. This messaging will undoubtedly include details around complex and sensitive issues. Communicating to the news media and fielding questions from reporters about major developments and decisions is a major facet of public information.

The Chicago, Illinois, Police Department used this approach when rolling out a revamped crime strategy that leveraged technology and real-time data analytics to combat an increase in gun violence. The communications team developed a multitiered “smart policing” education plan to inform the department, city residents, and policy makers on the advancements being deployed to reduce crime. This effort was also cast as a way to build support for police officers on the front lines. The end result was operational assistance from criminal justice and community partners and significant financial and technical resources provided by various philanthropic groups and academia.

It’s within the give-and-take of communications that relationship building takes place. Department heads come to rely on their communications staff for help framing the messaging for new initiatives and lean on them for insight during a crisis. Keeping the communications team in the loop can also help a department when it comes to strategic announcements. Often, police make small moves that go unnoticed by the public but have a dramatic impact on public safety. A communications professional will recognize these subtle changes and broadcast these otherwise-overlooked adjustments as significant steps toward building trust and improving safety.

A well-informed communications staff can also lessen the burden on investigative resources during high-profile incidents by serving as a clearinghouse and coordination engine for all aspects of internal, external, and executive messaging. For these reasons, there must be very tight alignment and collaboration between the investigative and operational functions of the agency and the communications office.

The “Drip, Drip, Drip” of Positive News

It’s important for any police department to maintain a steady drumbeat of positive news and have an innovative strategy for how to communicate these beneficial messages. A “drip, drip, drip” approach reaffirms key messaging. Regularly broadcasting new initiatives, both big and small, tells the public and the internal audience that decision makers are continually looking for ways to improve services to the community. Examples of outstanding police work may include putting a spotlight on positive community partnership initiatives, reinvigorated crime fighting strategies, or even a significant recovery of illegal guns and drugs. Any sort of lifesaving act or heroism and ways to humanize the badge are also stories that departments need to seek out and share.

Unless the public sees the selfless acts that police officers do every day, it’s as though they never happen. Another way to think of regularly broadcasting positive news is to create a “bank” of goodwill. Undoubtedly, there will be incidents that arise that challenge the public’s faith in a police department—particularly in the current environment—but amplifying a regular stream of examples of positive police work helps offset negative perceptions.

Positive news also builds allies, including elected officials, religious and community leaders, and other influencers. Those pictured standing beside the police as new public safety initiatives are announced and individuals seen participating in community-building events with police officers are more likely to stand up for these same departments during challenging times. At the very least, they may think twice before adding fuel to a situation that paints a negative picture of the police.

Traditional media continues to play a major role in publicizing positive news from police departments. While they are not the only messaging vehicle available, they are the largest, independent voice that must be embraced as a pivotal partner in educating the public. Given this, newspapers and television are undoubtedly seeing their longstanding audiences dwindle, but these same news organizations have built a considerable following online. Someone who may never pick up a copy of the paper or tune into the evening news could just as easily retweet a journalist’s online story or post a news organization’s video clip on his or her Facebook page.

Still, the impressive following traditional media outlets have on social media has not yet translated to additional income. As a result, newsrooms continue to shrink. This slump in journalism jobs is juxtaposed by an increased appetite for news. People everywhere are looking for articles to read and share on the devices they carry with them everywhere.

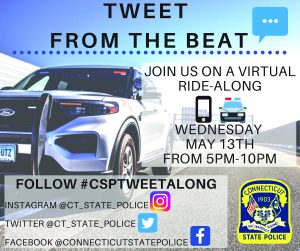

Police departments have an opportunity to take advantage of this appetite for information by developing their own social media and digital communication teams. These teams often function like in-house reporters with the goal of highlighting positive police work, meaningful community engagements, and initiatives designed to improve public safety.

Case Study: CPD Media Car

Facing formidable public trust challenges, the Chicago Police Department (CPD) sought to rebuild its reputation with renewed vigor in 2016 with the help of a communications team reporting directly to the superintendent. A group of roughly two dozen sworn officers and supervisors with varying operational backgrounds and interests in media relations, social media, video production, and public relations were paired with newly hired former print and broadcast journalists to create a blended cohort. The goal was to create a forward-thinking and functional communications unit that trumpeted strategic partnerships and took responsibility for all aspects of internal and external messaging for the United States’ second-largest police department.

Having the backing of the superintendent as well as alignment within the operational and investigative chain of command helped drive this rebranding effort that put a spotlight on the exemplary work of officers throughout the city and investments in technology designed to improve public safety. The Chicago team also built a rapid-response function that was ready to tackle any reputational crises on a 24-hour basis.

The CPD Media Car was arguably the most innovative communications solution to come from Chicago’s effort to rebuild its reputation. With the superintendent’s endorsement, this field-based public affairs unit became tasked with seeking out daily examples of proactive police work as well as stories of positive community engagement.

Two sworn officers working from a marked police vehicle deliver these stories directly to city residents and stakeholders through the department’s social channels and through a partnership with local news media. The positive stories are acquired by regularly visiting districts; listening to the citywide radio broadcast for breaking news; and maintaining relationships with community policing officers, commanders, and others who share tips in an effort to call attention to the good work happening within their units.

In addition to feel-good feature stories, officers on the CPD Media Car also have a critical incident response function. They arrive on the scene of a breaking incident and begin by establishing a media staging area. They can also answer any immediate questions from reporters. CPD Media Car officers then work with the supervisors to unveil the details of the incident. These details are relayed back to the office, where an official statement is crafted. This statement is then relayed back to officers in the CPD Media Car, who share it with supervisors on the scene.

Once approved, the statement is shared with local media through the main office as well as on the department’s social media channels. Typically, a supervisor will also read the statement on camera and answer questions for reporters who are gathered in the staging area. Officers working the CPD Media Car are well versed in the type of questions that will be asked and can rehearse the supervisor ahead of appearing on camera.

CPD Media Car team members also record the press gaggle and post the footage to the department’s Facebook page. This allows all stakeholders to hear the statement directly from a sworn supervisor and listen to his or her response to any questions. All these actions help improve transparency and responsiveness, while also inserting someone with a keen eye for community and public affairs into the mix as the department formulates an official statement.

All the equipment necessary to conduct a press conference is kept within the CPD Media Car. A branded podium and microphone are at the ready, as well as the necessary equipment to broadcast remarks from a chief or high-ranking official online. This may sound like it requires a significant investment, but it requires only an expandable podium, a cellphone that can connect to the internet, a microphone, and a steady tripod. With this basic equipment, press conferences are easily and professionally broadcast on the department’s Facebook page, typically using the Facebook Live function.

The accessibility of this technology and an agency culture that encourages creativity have also empowered officers in the CPD Media Car to shoot their own short videos, complete with music, cut scenes, and basic graphics. This is all done on department-issued phones and often from the front seat of the vehicle. The videos can amplify a message as simple as holiday greetings, pay tribute to a fallen officer through testimonials from coworkers, or use the words of community members to describe a situation where police arrived promptly and resolved a situation without incident.

In 2018, officers from Chicago’s graphic arts and media car teams along with professional staff won a regional Emmy award for their original work on a successful community education piece that told the story of Brix—CPD’s only cadaver search dog—and his battle with cancer.

Know the Audience Inside and Out

The primary audience for any police department’s messages is the public. Community support plays a vital role in improving public safety. Residents who see officers doing good deeds on their social media feeds and in the news are more likely to trust the police, which translates to 911 calls from concerned residents when they spot a suspicious person or activity, helping departments accomplish the sought-after goal of stopping a crime before it occurs at all. These same engaged residents are also more willing to serve as witnesses when a crime has occurred.

Agencies also might be interested to learn that a significant number of officers also tune into their social media channels and watch intently as news from the department is broadcast in the media. This is an important factor to keep in mind when developing messages. Namely, officers are paying close attention. They want to see the hard work they do reflected both online and in the media.

When the department isn’t portrayed accurately, it’s not uncommon for officers to take to social media and call out any disparities. Most departments have rules governing employee conduct online. However, there are also first amendment considerations and ways to get around even the most stringent directives regarding social media. Police unions are also likely to step up and call attention to a particular initiative or action if it is not in the best interest of their members.

Thus, it’s important to identify influencers within the department when making announcements that have the potential to upset the rank and file. A thorough description of how and why potentially unpopular decisions are made has more credibility when delivered by a chief or commander who has the respect of those under his or her command.

Former Journalists Offer Insight

Police departments throughout the United States also have come to rely on former journalists to help them with messaging. Local reporters will have a keen eye for the information contained within the press release or announcement. After years of working in the media, they instinctively know if the details provided by the department will answer the questions of their former colleagues.

Reporters also offer valuable insight in both the framing and timing of a story, having written or produced these stories themselves. Moreover, many seasoned journalists are more willing than ever to make the shift into communications jobs—particularly in the public sector, where many of them have spent years covering police departments and other institutions from the outside. This provides some ready-made familiarity with the department as well as a level of job stability that is increasingly rare within the modern media landscape.

Conclusion

Regardless of who is staffing the office, communications and messaging should not be an afterthought—it has to be strategic and proactive when possible. Aligning PIOs with top level-executives and putting these messaging experts in the room when decisions are made remains the key component to building a successful communications function.

The emergence of social media and the increasing demand for regular updates and transparency by the public open the door for creative strategies that engage the community and build trust. With that in mind, a communication team ought to be seen as an ally in creating safe communities with residents who are truly engaged in maintaining public safety.

|

Howard Ludwig is an award-winning journalist now serving as a public information officer and executive speechwriter for the Chicago, Illinois, Police Department. He previously covered the police and neighborhood beats for two of Chicago’s most prominent newspapers. |

|

Anthony Guglielmi headed the communications offices for the U.S. Office of Special Counsel as well as the Baltimore, Maryland; Chicago; and now Fairfax County, Virginia, Police Department. He is the current public information co-chair for the Major Cities Chiefs Association and a regional chair for the IACP Public Information Officers Section.

|

Please cite as

Howard Ludwig and Anthony Guglielmi, “Traditional Public Information Offices Must Evolve into Aligned, Strategic Communications Operations,” Police Chief Online, March 31, 2021.