Many police agencies face staffing and resource constraints that require officers to prioritize violent crimes over other types of crimes for investigation and victim support. Police-based victim service providers face similar constraints and often focus on specific types of violent crime, such as sexual assault or domestic violence. Even though crimes like burglary can result in serious financial losses and an array of psychological harms for victims, including anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, and fear for safety, most residential burglaries go unsolved. Victims rely on police to recover stolen property, apprehend perpetrators, and help restore their sense of safety, and when this does not happen, the lack of attention and investigative progress can leave victims feeling dissatisfied with and less trusting of police. Victims may then be less likely to report future crimes or assist police with investigations.

Artificial intelligence (AI) provides a potential solution for police agencies faced with the challenge of limited resources for addressing certain types of crime and providing information and support to victims. Existing research in other fields suggests that virtual assistants, also known as chatbots (chat + robot), can be a useful tool for providing customer support, automating routine functions, and providing answers to standard questions.1 With funding from the U.S. Department of Justice Office for Victims of Crime, and in collaboration with the Minnesota Alliance on Crime, the Identity Theft Resource Center (ITRC), and the Greensboro Police Department (GPD) in North Carolina, RTI International developed and tested the Enhanced Virtual Victim Assistant (EVVA), which was designed to address the lack of justice-system based resources and responses available for burglary victims.

The pilot test of EVVA with GPD, along with reflections from GPD on their experiences implementing the chatbot, presents important considerations for the development of a chatbot.

What Is a Chatbot and What Are Its Uses and Benefits?

Chatbots are computer programs that hold online “chats” or conversation via text or through a website. Chatbots simulate conversations that a user would typically have with a human representative from a company or agency. They range in sophistication from rudimentary programs that answer a simple query with a single-line response to digital assistants that leverage AI and machine learning (ML) to learn over time and deliver increasing levels of personalization as they gather and process information.

Often chatbots are used to provide customer service, such as answering questions about an order from an online store or helping users to navigate an administrative process for a government agency, like a department of motor vehicles. Chatbots have been used across a variety of industries to automate repetitive tasks, respond to frequently asked questions (FAQs), or collect information from individuals. Chatbots can help to reduce organizational burden through reducing staff workloads and improving efficiencies in carrying out administrative tasks by answering FAQs that would otherwise come through the office via phone, email, or in-person inquiries. They can provide more timely responses to questions than someone would get if they had to wait for a staff person to return an email, text, or phone message.

Often chatbots are used to provide customer service, such as answering questions about an order from an online store or helping users to navigate an administrative process for a government agency, like a department of motor vehicles. Chatbots have been used across a variety of industries to automate repetitive tasks, respond to frequently asked questions (FAQs), or collect information from individuals. Chatbots can help to reduce organizational burden through reducing staff workloads and improving efficiencies in carrying out administrative tasks by answering FAQs that would otherwise come through the office via phone, email, or in-person inquiries. They can provide more timely responses to questions than someone would get if they had to wait for a staff person to return an email, text, or phone message.

Although chatbots are often used in the customer service industry, their potential benefits extend to the criminal justice system. Chatbots have the potential to improve efficiency, redefine engagement, reduce administrative costs, and—possibly—expand access to information related to justice system processes. There are examples of chatbots being used across the criminal justice system for police, courts, community supervision and victim service purposes.2 Within police agencies, chatbots have primarily been used for recruitment and investigation. On the recruitment side, agencies like the Los Angeles, California, Police Department use chatbots to answer FAQs related to officer recruitment and hiring.3 On the investigation side, agencies in New York; Los Angeles; Chicago; and Boston have used chatbots posing as someone selling sex to identify and deter buyers and, in the cases where the individual poses as a minor, combat child sex trafficking.4

In the community, chatbots have also been used to support victims of crime through identifying sources of support and helping victims document instances of crime to aid future reporting or legal options. For instance, ITRC created a virtual assistant to assist victims of identity theft by providing information about how to safely store and secure documents and personal information and key steps an individual may take to mitigate the impact of identity theft. Although chatbot users can request to speak with a live expert advisor during business hours, the chatbot makes the information and support available 24/7. Beyond the United States, in countries such as Switzerland, Thailand, and the Philippines, chatbots have been designed to support victims of domestic violence and sexual harassment with resources or documentation of events.

Based on the current uses of chatbots, this technology has the potential to enhance police departments’ ability to respond to certain victim needs, such as answering common questions about the investigative process and providing information and referrals that may assist victims in their recovery. Chatbots offer the opportunity to improve the police’s ability to respond to the informational needs of victims and refer them to community-based support and services without an additional drain on limited resources.

Developing and Testing EVVA

A chatbot is not an “off-the-shelf” technology; it requires development, customization, and human oversight to ensure it provides relevant information and is protected against its misuse or potential privacy and security risks. RTI’s chatbot, EVVA, is the first known chatbot intended for use by police agencies to provide information directly to victims, specifically victims of residential burglary who reported the incident to police. Because EVVA is the first use case of its kind, RTI staff spent extensive time determining what information and support would be useful to victims of burglary, which of these needs a chatbot could address, what common questions victims would ask of police, and how to ensure that police practices related to the investigation were accurately communicated by the chatbot.

To ensure that the perspectives of persons who experienced a burglary were represented in the development of EVVA, the RTI team sought victim input at all stages of the project. Additionally, the team routinely engaged in conversations with police agencies throughout development and testing to ensure that EVVA would provide value and could be easily implemented.

RTI staff first conducted interviews with victims. Based on these interviews, the team identified possible scenarios or reasons why someone would interact with EVVA. From there, the staff worked with several police agencies to better understand how the chatbot should be programmed to respond to these requests. EVVA was programmed to respond to more than 60 types of questions that burglary victims commonly have. Examples of the information that EVVA can provide include the following:

-

- How to request a copy of a police report

- How to get contact information for the department or investigator

- How to file an insurance claim

- Ways to secure a home after a burglary

- What to do if documents with personal information were stolen during the burglary

- What type of community-based services are available if the victim needs different types of assistance

After building the chatbot to address these key victim requests, RTI conducted usability testing with about 30 residential burglary victims to see how they interacted with the bot and to gather feedback on how EVVA responded to their inquiries and requests. Finally, after the feedback was incorporated, RTI conducted an extensive pilot test with GPD.

GPD has a long history of embracing opportunities to participate in research and technical assistance projects, including several with RTI. Because of this, and GPD’s well-established thought leadership in innovative policing, the RTI project team approached the department about the opportunity to integrate EVVA into GPD’s technical and operational systems. GPD leadership worked with the project team to engage in discussions about the utility of EVVA and how the chatbot could be technically and operationally integrated across a wide range of divisions. Once GPD officially agreed to participate in the pilot test, they provided the team with the access needed to integrate the chatbot with the records management system (RMS). To enable RMS functionality, GPD provided an extract of burglary-related case data, uploaded daily to a secure online file hosting service accessible by the chatbot. EVVA could then pull from the RMS to provide victims with direct, up-to-date information about their case based on their report number. The information pulled from the RMS was restricted to that which would be publicly available if requested at the agency. RTI worked with GPD to ensure that EVVA provided correct information about processes for requesting a police report or a safety check and that EVVA could offer the same referrals to local community-based services that officers and other GPD staff would typically provide.

| Figure 1: EVVA Sticky Note |

|---|

|

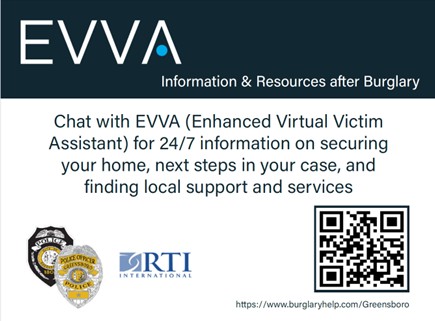

RTI and GPD also worked together to develop low-burden, affordable mechanisms for officers to provide information about EVVA to victims and to train officers on how and when to provide this information. The RTI team created sticky note pads, designed to fit in an officer’s shirt pocket, with information for victims on how to access EVVA. The notes, as seen in Figure 1, provided both the web address as well as a QR code that could be scanned with a smartphone camera to access EVVA. Officers can peel a sticky note off the pad and hand it to a victim or stick it on a copy of the police report.

For training officers and staff on sharing information about EVVA, the RTI team created a short training video, shared through YouTube, that officers and staff could easily view at any time. The training could also be shared during roll call or in training modules. Finally, RTI worked with GPD leadership to implement a tracking process to ensure that officers were providing the sticky notes to burglary victims. Officers were instructed to add a brief note in the incident report, which would then be reviewed by the Crime Analysis Unit to identify if officers needed to be retrained or reminded about sharing the resource with victims.

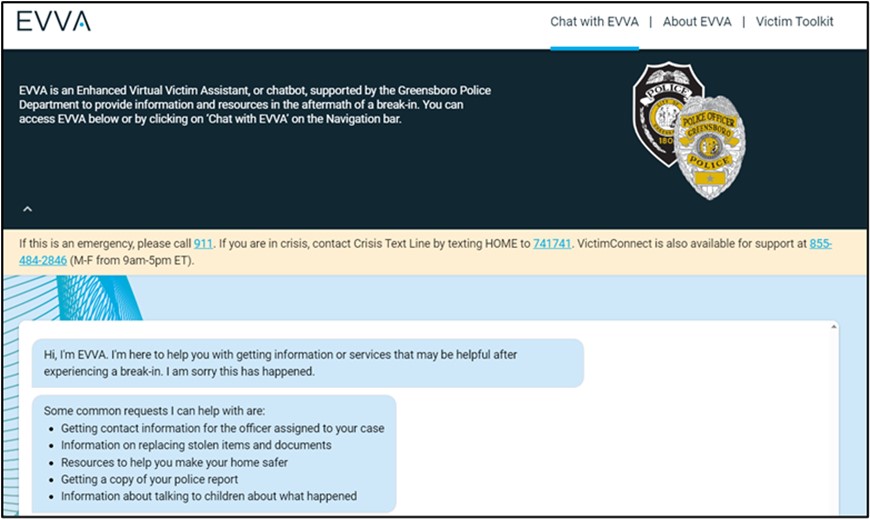

The pilot test launched in Greensboro on August 1, 2022, and ended just over a year later. The launch was accompanied by press releases from RTI and GPD, which received media coverage and demonstrated the department’s commitment to and genuine interest in the project.5 Figure 2 shows what the EVVA interface looked like for victims who accessed and used the chatbot.

| Figure 2: Screenshot of EVVA GPD Home Screen |

|

Throughout the pilot test, GPD had 479 officer referrals to EVVA. These referrals resulted in 81 victim conversations with the chatbot. The top victim question for EVVA action was asking about next steps in the investigation, followed closely by asking for the contact information of their investigator, how to receive a police report, and the status of their case. As part of the process of continually training EVVA to better interpret and respond to questions, RTI staff manually reviewed each of the conversations to assess user satisfaction with EVVA’s responses. The team coded conversations based on whether they ended with a user getting a response and leaving the chatbot or a user expressing frustration and seeming unable to get an answer that addressed their needs. Based on this coding, the majority of users were satisfied with the conversation (71.6 percent).

GPD Reflections on Implementing EVVA

GPD realized the importance of AI and the possibilities that EVVA could offer in responding to victims. GPD was able to customize the responses to many anticipated questions from victims that would best suit the agency. EVVA did provide a thorough response to often difficult questions. For example, when a victim of a burglary loses personal identifying documents during the theft, detectives would spend a considerable amount of time discussing the steps to prevent future loss from ID theft. EVVA could provide the resources and links to help with ID fraud. The messages provided to victims are always a consistent response; whereas, a live person may forget to mention a resource or have difficulty providing links to available online resources. EVVA could provide this uniformly to victims.

During the implementation stage, GPD continued to develop ways to help victims of burglaries access EVVA. One of those ways included adding the sticky note graphics to the agency’s existing Victim Rights Forms. This form is provided to any burglary victim after a report is filed to include important information about the case, providing a case number for the case, and phone numbers for the Criminal Investigations Divisions (CID), allowing the victim to refer to it at a later time if needed. GPD felt that in some instances, when further context was needed or answers included certain agency-specific terms, which may be confusing, it would be easier for a GPD employee to discuss it with the victim at a later time. In these situations, EVVA would ultimately refer the victim to the CID to speak about case status directly. A GPD victim advocate or a detective could then explain the case disposition, providing context or a more in-depth response. Overall GPD had positive interactions involving EVVA and believes that the chatbot could be expanded in other places in the agency.

Important Considerations for the Use of Chatbots for Responding to Victims

The development and testing of EVVA revealed many considerations that agencies should keep in mind when considering the potential uses of this technology.

When considering developing a chatbot, it is crucial to think through possible misuses of the chatbot and ensure that the information provided will not compromise someone’s safety or security. During interviews and usability testing of EVVA, victims expressed the desire to have a chatbot communicate information specific to their case. Although EVVA was able to link to the RMS and provided limited case information, which was one of the most common reasons users engaged with the chatbot, the project team agreed that EVVA should share only publicly available information that anyone could request directly from the agency. Given limitations on a chatbot’s ability to confirm someone’s identity, the release of information that would require proof of a person’s identity to meet the request was not programmed into EVVA. When considering future use cases of the chatbot within the criminal justice system, careful consideration of the types of information the chatbot provides is crucial to ensure that individuals’ information is protected and that information that could compromise someone’s safety is not released.

| “Because EVVA was designed to provide support to victims of crime, the tone and ‘voice’ of the chatbot was particularly important.” |

Best practices in chatbot development suggest that there should be clear communication about the privacy and security of the information users provide. This was particularly important for EVVA’s development because, as a tool implemented by the police, the information was not confidential. Informing users early on that chats would be shared with the department should they disclose additional case information or details was important given research that suggests clarity on data security and privacy practices are linked to whether users trust a chatbot.

Because EVVA was designed to provide support to victims of crime, the tone and “voice” of the chatbot was particularly important. Guidance on the development of chatbots suggests that it is important for chatbots to not be overly humanized, while still providing empathic responses. Chatbots that just provide information without expressions of sympathy tend to be less favorably received by users.6 Additionally, usability testers of EVVA emphasized the importance of messages that validated their reactions to burglary and expressed empathy.

Not all topics or conversations are appropriate for a chatbot to engage in with victims, such as sensitive topics that require emotional support, topics that require handling of non-public data, or cases where a chatbot does not understand what the user is trying to achieve. In these cases, having live victim services personnel available to continue the conversation may be appropriate to enhance the user experience. This process, referred to as chatbot/human handoff, can look like providing contact information for a human or transferring the chat directly to live support. Incorporating live human access increases the cost of providing a chatbot considerably, especially if the desire is to have this resource available 24/7. However, if resources are available, this feature can help improve the quality of a user’s experience with a chatbot.

In addition, considerations around the intended user of the chatbot are an important part of the development of a chatbot in any setting. For instance, considering if and in what languages the chatbot can be accessible to users should be informed by the population that the police agency services. The pilot test version of EVVA was able to respond only to questions in English. Police agencies that serve communities with sizable non-English-speaking populations may consider extending the development of EVVA to enable multilingual conversations. Adapting conversations should be done in partnership with individuals in the community who speak the language to ensure that the translation is relevant to the dialect and terminology used in the particular community. Another issue that came up during the pilot test was the lack of familiarity with the concept of a chatbot. Victims who have limited access to internet-enabled devices or limited technological skill for using things like QR codes may have challenges accessing EVVA, since it is a web-based application. Technological challenges can be mitigated to some degree by departments providing brief instructions to victims on how to access EVVA. However, this also requires that officers understand what a chatbot is and have practiced with one enough to explain it clearly to a victim. Thus, it is important to identify the intended users of a chatbot and assess whether the chatbot will be accessible to them and meet most of their needs.

Other Potential Applications for Chatbot Technology

The potential applications for chatbot technology within policing are extensive. A chatbot could be used to recruit future applicants to the agency. When potential applicants are researching which agency to apply to, especially within an increasingly challenging market, agencies should provide answers to FAQs quickly and easily. Having a chatbot available to answer salary and benefits questions 24/7 allows the applicant to receive the information when they want it. The chatbot could also help applicants navigate the lengthy application process.

Expanding chatbots to include other types of crimes such as fraud-related offenses or motor vehicle thefts could provide similar assistance to the victims. In fraud cases, the chatbot could help victims secure their identity from future theft. In motor vehicle theft cases, the chatbot could inform victims of the proper steps for filing a claim with their insurance company. The chatbot could be used to further investigations by integrating Crime Stoppers programs and tip lines to allow residents to quickly provide tips on illegal activity or information on wanted subjects that could then be provided to assigned detectives for follow-up.

Providing QR codes or a small kiosk in the lobby of agencies could help to provide customer services to residents. Often websites are limited, out of date, or difficult to navigate to find the information needed. A chatbot could help answer questions or guide users who wish to make a request. Examples of some of the questions a chatbot could provide information on include

Providing QR codes or a small kiosk in the lobby of agencies could help to provide customer services to residents. Often websites are limited, out of date, or difficult to navigate to find the information needed. A chatbot could help answer questions or guide users who wish to make a request. Examples of some of the questions a chatbot could provide information on include

-

- How do I hire an off-duty officer for an event?

- How do I request additional traffic enforcement in my neighborhood?

- How do I request an officer to speak at a community meeting?

- Whom should I speak to about a problem in my community?

The success of a chatbot depends on its acceptance by potential users and the messaging provided to the community. An additional way to publicize the program could be the addition of QR codes to police vehicles, other city-owned vehicles, or mass transportation so residents will see the code and hopefully trust and use it to better connect with their department. The increasing number of individuals open to communicating with AI instead of a live person offers police more ways to communicate using modern technology. The connections made between the community and policing agencies using AI can help improve interactions and hopefully provide positive experiences on which to build.

Conclusion

There are many opportunities for a chatbot to be incorporated into a police agency’s daily functions, including assisting victims of residential burglaries. Advancements in AI, such as the development of empathetic technology and large language models like ChatGPT, will continue to drive chatbot development and increase the potential for this technology to benefit police agencies and victims of crime.7 d

Notes:

1Solomon Negash, Terry Ryan, and Magid Igbaria, “Quality and Effectiveness in Web-Based Customer Support Systems,” Information & Management 40, no. 8 (September 2003): 757–768.

2Meghan Camello, Michael Planty, and Jaclyn Houston-Kolnik, Chatbots in the Criminal Justice System: An Overview of Chatbots and Their Underlying Technologies and Applications (National Institute of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice, 2021).

3Theo Douglas, “Los Angeles Chatbot Deputized to Help With Police Recruitment,” Government Technology, February 16, 2018.

4Tina Rosenberg, “A.I. Joins the Campaign Against Sex Trafficking,” New York Times, April 9, 2019.

5Peter Stratta, “Greensboro Police Implement Chatbot Technology for Burglary Victims,” ABC News, August 30, 2022.

6Bingjie Liu and S. Shayam Sundar, “Should Machines Express Sympathy and Empathy? Experiments with a Health Advice Chatbot,” Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking 21, no. 10 (October 2018): 625–636.

7Camello, Planty, and Houston-Kolnik, Chatbots in the Criminal Justice System.

Please cite as

Lynn Langton et al., “Using AI to Enhance Victim Response,” Police Chief Online, July 31, 2024.