In recent years, policy makers have dedicated a lot of attention to cybersecurity, artificial intelligence, and privacy, especially in relation to video surveillance and public safety. While these are very important topics, some attention should also be dedicated to the more fundamental issues that often go unnoticed and relate to the proper understanding of image and video evidence, both during investigations and in court. The intention of this article is to raise awareness about the video evidence’s challenges as “you don’t know what you don’t know”: the very first step in addressing a problem is realizing that you have one.

It’s widely recognized and corroborated by scientific studies that images and videos are the most effective sources of evidence, yet unfortunately, they are not always treated with the same rigor and scientific approach that is applied to other forensic fields.1

This dichotomy is sadly present even in the pop culture: on the one end, in every investigative fiction, à la CSI, DNA, toxicology, and fingerprints forensic experts come to the crime scene or are in the lab, with extreme professionalism and a white coat; on the other end, when there’s a video to analyze, a random investigator screams at the screen “Zoom in on that!” This is very indicative of the public perception of video evidence and how its complexities and challenges are underrated.

It is commonly said that “with great power comes great responsibility.” Given the power and amount of video evidence often available, the risk of letting a criminal go free or destroying the life of an innocent person being accused on the basis of a misleading analysis is extremely high. For this reason, it’s of utmost importance to treat it very seriously.

Challenges of Video Evidence

What are the issues that often arise when working with video evidence?

1. Video evidence seems easy, but it’s actually easy to get it wrong.

Anybody can hit “Play” or download a photo on their PC and try to interpret it. These very low entry barriers imply that those who have to deal with video evidence may not have the right technical preparation or the right tools. Why? Everybody can “watch” a photo.

There are a number of pitfalls that can happen if somebody is not aware of the technical limitations of video evidence and the bias of the human visual system in their interpretation. The following two examples are probably the most common and dangerous issues.

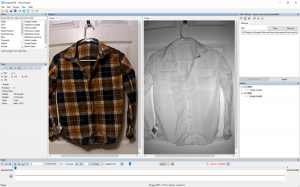

Infrared Imaging. Most video surveillance cameras in low light conditions use an infrared illuminator. In this case, the values of the pixels that represent an object in a video file don’t have any relation with its real color. For example, the fact that a shirt seems “bright” in an infrared image doesn’t imply that it’s actually of a bright color (it could even be black), but it just indicates how its fabric reflects the infrared. If this fact is not known, it can easily cause identification errors and mislead an entire investigation. Infrared and visible light are two completely different signals that can’t be used to directly compare colors, but if the work is done with the awareness that infrared imaging has this limit, the judgment won’t be biased by a misleading representation.

Figure 1 shows pictures of the same shirt taken by the same camera, in the same position, with both visible light and infrared. It can be noticed that the two images seem to portray two completely different shirts. Not knowing of this effect can lead the investigation in the wrong direction and potentially cause a wrong identification.

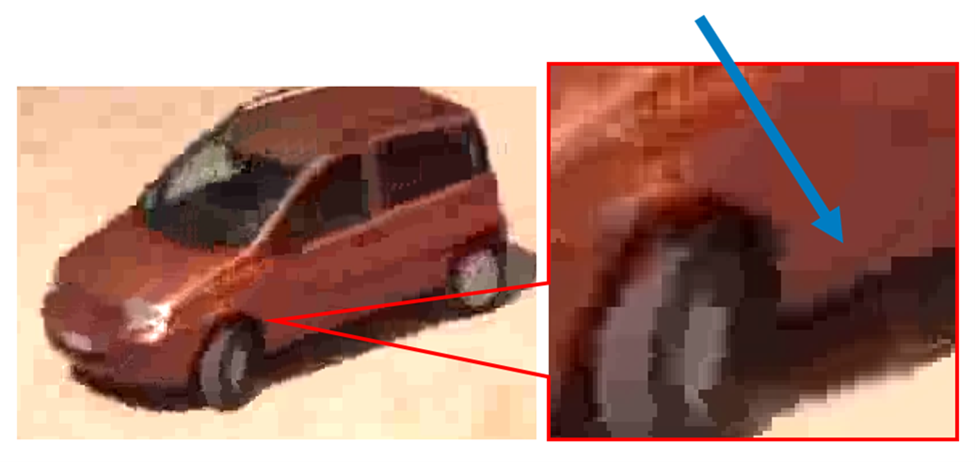

Digital Compression. Compression is applied to most images and essentially all videos in digital format. Without compression, the storage space on most phones would allow for filming for a few minutes at most. After that, the memory would be full. Furthermore, sharing videos on the internet would be practically impossible. What does compression do? It reduces the amount of data, exploiting redundancies and similarities inside a video frame and consecutive frames. It also removes less perceptually relevant details from the video. If this happens to vacation photos, this is useful and sensible. However, when speaking about the forensic context, this process may remove small but very important details and even create new fake details (called “artifacts”).

With the proper technical preparation, it’s possible to understand which parts of the image to rely upon and which ones can’t be trusted. This will minimize the bias that an investigator could have, for example, when trying to interpret the characters of a license plate in a low-quality image.

Furthermore, it is important to remember that the fact that something is not visible in a video doesn’t mean that it didn’t happen. Frame rate, resolution, compression, and other factors heavily affect its interpretation. During a trial, it’s not uncommon to discuss the reliability of a block composed of a few pixels.

For example, in Figure 2, it’s very difficult to understand detail on the side of the car; it seems like a scratch, but it is actually an artifact of the compression.

2. Proprietary video formats complicate investigations and introduce cybersecurity risks.

The vast majority of files coming from video surveillance systems are in proprietary formats. This means that they are not normal MP4 or AVI files that can be played with standard software, such as Windows Media Player or VLC; instead, they need the player created by the system producer. Very often, these players are of low quality, have significant issues, and are completely inadequate for a forensic analysis of the video.

In order to perform video analysis, proprietary files need to be converted. This is another critical phase. A conversion done without the right care can very easily introduce the following issues:

-

- The loss of file originality, with a clear impact on the chain of custody that must be ensured for every kind of evidence.

- The loss of quality: if the video is transcoded, this may cause a noticeable quality loss.

- The loss of metadata and information about the original encoding, such as timestamp and the kind of compression applied on different parts of the image; this information could have been used to evaluate the reliability of the visual information.

Furthermore, the search and use of proprietary players can cause many issues from the IT and cybersecurity points of view.

3. Image quality is often low: it must be processed in the right way.

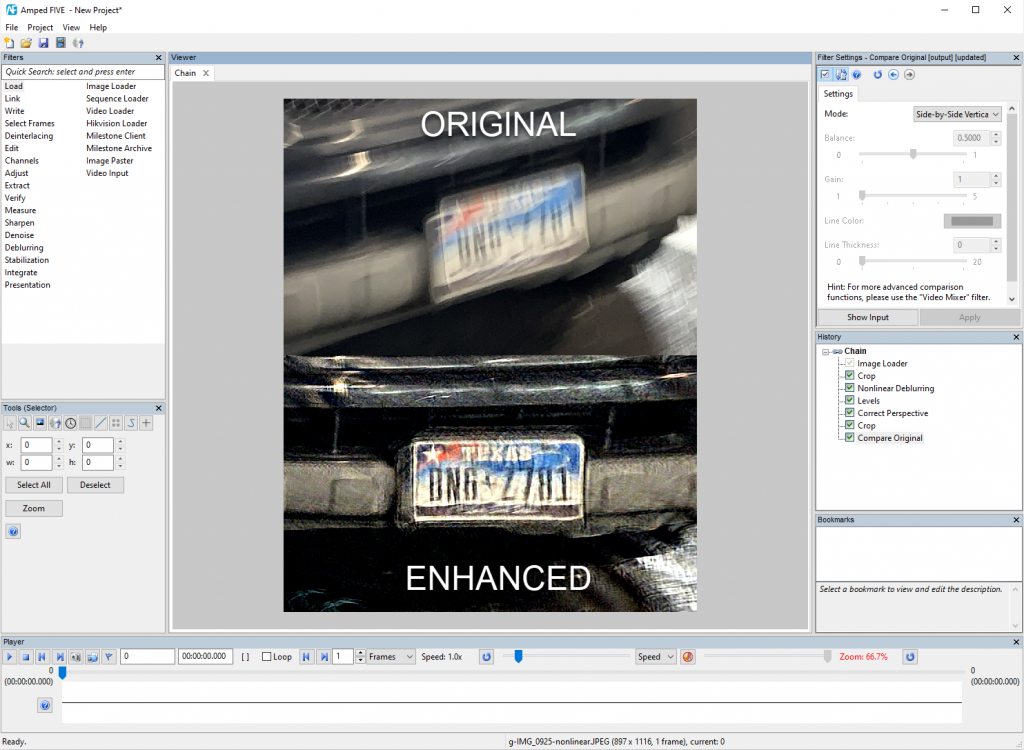

Video evidence often doesn’t have sufficient quality to obtain the needed information, for example, to identify a person or a vehicle. However, using the right tools and techniques, if there are the right technical conditions, it is possible to get excellent results.

The processing must be done in a rigorous way, using methodologies applicable for the forensic settings and scientifically validated, otherwise, the evidence could be disqualified during the trial. According to research carried out with Amped Software products users, video enhancement can produce useful results in about 50 percent of the cases.

Figure 3 shows an example of a forensically enhanced video with Amped FIVE.

4. Video evidence can’t always be trusted due to deepfakes, manipulation, and misattribution.

Authenticating images and videos is becoming of utmost importance. Lately, deepfakes (image manipulation with artificial intelligence techniques) are everywhere in the news, but in reality, it’s much more common to see very simple fakes.

It’s not even needed to modify an image to use it in a malicious way: just think about the reuse of a photo done at another time or the staging of an event used as evidence. All this is much easier to do than a deepfake. Image and video manipulation are a real possibility, and they need to be taken into account when starting to analyze video evidence.

5. Forensic video analysis requires interpreting in the right way without bias.

A critical part of video evidence analysis is determined by human factors. One of the most pressing issues is to limit human bias during the interpretation. Again, even just being aware of the issue is a good start. It is very important to give investigators or analysts only the strictly necessary technical information to perform their job and to apply bias mitigation techniques.

It is very easy to get “too involved” in a case and instinctively look for confirmation of one’s beliefs and opinions. This can, and often does happen, because analysts and investigators are humans. Even without any malicious or explicit intent, the human mind naturally uses biases as a shortcut to understanding difficult situations.

6. Judges and juries are easy to mislead on technical topics.

It’s often difficult for judges, juries, and the public to evaluate the technical ability and reliability of the various sides’ expert witnesses. Let’s say that one side does a correct and very cautious analysis. The other side is less careful with respect to the various forensic procedures but gives a much stronger speech, maybe with an opposite outcome of the analysis. Often this is enough to cast doubts on the previous analysis, even if that was the correct one. Without a minimum of scientific and technical education and awareness, this is a very difficult issue to overcome.

Often, the ability to communicate is much more important than the actual correctness of the analysis.

7. Artificial intelligence, privacy, and cybersecurity impact video evidence.

These points are not specific to video evidence and forensics, but they should be taken into account in this context as well.

Using artificial intelligence to work on video evidence should be handled with care. AI processing, in fact, usually introduces some bias that depends on the data used to train the system and its of limited explainability, limiting the applicability of the same on image and video to be used as evidence in court.

Regarding privacy, there’s a natural tension between the need to acquire as much data as possible during investigations, their forensic use, and privacy considerations. Nevertheless, working within the boundaries of privacy regulations is a very important aspect that should be taken into account even by law enforcement. Worldwide, there’s growing adoption of stricter privacy frameworks that typically follow the steps of the European GDPR. Law enforcement isn’t exempt from such regulations. Quite the opposite, actually.

Finally, the cybersecurity aspect is very important. Forensics and investigation are by nature sensitive industries, where data and security must be taken very seriously. Software and systems should be safe, as much as possible.

How to work correctly on image and video evidence?

The above-mentioned issues could be solved. Awareness and culture on this topic should be created at 360 degrees, starting from police officers to forensic analysts, judges, prosecutors, attorneys, up to politicians and the general public. These issues should be solved both down and up the chain of command.

Once it is understood that video evidence should not be taken for granted, but should be handled scientifically and with care, awareness programs for all the parts of the judicial system should be created. It’s not needed, nor recommended, that all police officers, attorneys, and judges became forensics experts, but it’s essential to create a cultural basis where everybody understands the importance and sensitivity of video.

What are the main points?

Awareness and education

Educating the users and the public on the pitfalls and complexities of video evidence. Expose people involved in the field to some form of a short education program (a few hours) to open their eyes to the concepts that are currently unknown to most people.

Originality and acquisition

Maintaining the chain of custody to guarantee access to the original evidence that has been acquired. All the operators should understand the importance of a correct acquisition. Too often there is surveillance video footage wrongly captured filming a screen with a smartphone. Without going to these extremes, even the simple exporting from a surveillance system or a digital video recorder (DVR) should be done in a way that preserves the chain of custody. This would grant the best possible quality and reduce the risk of the evidence being rejected in court.

Authentication and verification

Verifying the integrity of the file (is it original and unaltered?) and how much its content authenticity can be trusted. Furthermore, this process should be able to verify that the acquisition has been done properly.

Correct and transparent processing

Adopting clear guidelines for processing, using algorithms validated by the scientific community, and adopting a workflow that is correct, repeatable, and reproducible. There are several guidelines of excellent quality available, such as SWGDE and OSAC. Those should be more widely followed and adopted.

What can be obtained by working properly with images and videos?

- Better security

Working correctly would allow users to streamline the processing workflow instead of reinventing the wheel every time. While it’s true that every case is different, in the end, the underlying issues and objectives of an investigation are often very similar: most of the time, the purpose of the analysis is identifying a person, a vehicle, or understanding the dynamics of an event.

Working correctly would lead to the solving of more crimes and, thus, improve the security of our cities and countries.

- Better justice

Using original data, assessing their authenticity and integrity, and processing them in the right way can grant a fairer trial and reduce judicial errors.

- More speed, fewer costs

Doing things the right way doesn’t take more time since it actually involves a more efficient workflow. This means less time spent by human resources and fewer issues caused by mismanaged evidence.

There are only advantages to working on video evidence in the right way. Only one thing is needed: a change of mindset. Video evidence is not just “a video,” it’s evidence, and should be treated as such.

|

Amped Software develops solutions for the forensic analysis, authentication, and enhancement of images and videos to assist an entire agency with investigations, helping from the crime scene, up to the forensic lab, and into the courtroom. Amped solutions are used by forensic labs, law enforcement, intelligence, military, security, and government agencies in more than 100 countries worldwide. With an emphasis on the transparency of the methodologies used, Amped solutions empower customers with the three main principles of the scientific method: accuracy, repeatability, and reproducibility. |

Note:

1Matthew P.J. Ashby, “The Value of CCTV Surveillance Cameras as an Investigative Tool: An Empirical Analysis,” European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research 23 (April 2017): 441–459.