One of the many challenges law enforcement faces is identifying emerging threats to public safety while minimizing any violations of civil rights and liberties, such as, according to the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, freedom of assembly and speech.

There have been events over the past five to seven years within the United States concerning extremist violence by many different groups including the following:

-

- Anarchist groups and individuals such as Antifa.

- Conspiracy theorist groups and individuals such as Q-Anon.

- Right-wing groups and individuals like the Proud Boys.

These “extremists” follow a theoretical framework: Each believes the government has broken the social contract.

Extremism refers to violent and nonviolent forms of political expression, whereas terrorism is predominantly violent. Targeting nonviolent extremism as terrorism is problematic because it directs counterterrorism efforts against people’s political identities instead of political violence. So how do law enforcement and the U.S. intelligence community prevent, disrupt, and mitigate actions (some violent) by those individuals or groups labeled extremists? How can understanding the social contract theory help present evidence and trends to mitigate the violent behavior of these extremists?

To clarify, according to the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, the social contract theory refers to the philosophical view that persons’ moral or political obligations are dependent upon a contract or agreement among them to form the society in which they live.1

Another issue is that extremism gets labeled “movement” or “danger to the public” or even “terrorism.” However, that constitutes the legal definition of “extremist” that is NOT terrorism-centric? According to the Federal Bureau of Investigation and US Federal Criminal Code and Rule, the definition of domestic terrorism is not a charging statute, but definitional statute.2 Furthermore, the FBI stipulates that their threat categories use “the words ‘violent extremism’ because the underlying ideology itself and the advocacy of such beliefs are not prohibited by U.S. law.” This leads to this blurring of what authorities call either “extremists” or “terrorists,” regardless of domestic or international intentions. According to U.S. Rep. Eric Swalwell and policy advisor R. Kyle Alagood, the U.S. “counterterrorism efforts have been largely focused on international terrorist groups. However, since the September 11, 2001, attack, there has been a progressive resurgence of violent behavior committed by far-left and far-right extremists in the United States and Western Europe.”3 For the past 20 years, the focus has been primarily on international terrorism with little legal debate as to what constitutes domestic extremists or domestic terrorism. As identified above, the domestic terrorism definition is just that, with no charging statute attached. International terrorism concludes its definitional statute with a charging statute. Thus, there is a lack of conversation about what constitutes a clear and present danger of or by “extremism” within the context of U.S. Constitutional law.

The investigation of potential violent extremist behavior can include the identification of a person’s alignment to what might be considered an extreme viewpoint; that alignment can be identified through proactive communication with the community that promotes transparency of the government’s fulfillment of the social contract, identified as the U.S. Constitution. This establishment of a relationship builds reciprocal trust and can be beneficial to the community. The relationship begins with daily interaction between law enforcement and the community. A law enforcement application of respectful public interaction can include listening to the voices of all community members. This strategy can minimize physical conflict between members of the public and government representatives that can be caused by miscommunication.

However, caution is to be exercised with collaborative activities involving the news media, as social and news media can highlight the controversial incidents of the conflict. This is not to say the reporting of information is not needed; however, violent extremists utilize the power of media to bring attention to their plans. Swalwell and Alagood state that “the proliferation of internet access, social media, and algorithmic sorting of digital information online has helped fuel domestic extremist ideology and given extremists a low-cost medium for publicity.”4 Examples of the influence of online media include conflicting information about conspiracy theories and the government’s challenge to minimize undesirable public perceptions when only partial information is shared by government officials. This media attention can spark other violent conflict by groups and the lone-wolf individual. The criminal justice community can utilize various media resources to share information for community awareness of issues that may stimulate violent behavior with various alternative resources that may be available to enable peaceful and lawful resolutions. This communication strategy is a collaborative process with social and workplace institutions that can share alternative resources for conflict resolution. For law enforcement, the communication strategy would involve processes designed for de-escalation of conflict utilizing both the media and the actions of officers on the ground.

This strategy may appear simplistic; however, the person with the extremist disposition may reside in any neighborhood. Criminal justice professionals rely on the neighborhood’s people to share information about the potential criminal behavior of a violent extremist. Existing programs promoting community awareness communication, such as See Something, Say Something, and a national network of intelligence or fusion centers are successful components to mitigate associated violent behavior.

This strategy may appear simplistic; however, the person with the extremist disposition may reside in any neighborhood. Criminal justice professionals rely on the neighborhood’s people to share information about the potential criminal behavior of a violent extremist. Existing programs promoting community awareness communication, such as See Something, Say Something, and a national network of intelligence or fusion centers are successful components to mitigate associated violent behavior.

Tactics

Each group and its individual cadre have been able to glean tactics to ensure their message is broadcast. Much of this has been done through the use of social media such as Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter, whether it is used to plan, coordinate, and show their movement’s events. Far-right extremists’ tactics and strategies that they implement to communicate their ideology are different from their counterparts.5 This is evidenced by their expanding influence to achieve their intended goals. Furthermore, they utilize physical and psychological methods, including tools meant to manipulate individuals, justify their actions, and accumulate group power. This is in contrast to far-left extremists who have a significant following of generational means. Far-left groups look to influence and spread propaganda and communications, planning, and operations primarily through social media. Although far-right may also utilize social media, it has been reported that they do so less than their counterparts.

While it appears that political extremism is out of control today, people would do well to remember that the United States was born out of political extremism. Unfortunately, the United States is experiencing political extremism today by both the extreme left and extreme right. One only needs to examine how the Senate Judiciary Committee confirmation hearings for the 45th president’s selection for the U.S. Supreme Court (Justice Brett Kavanaugh) demonstrates how extreme certain groups of people can become. But, despite the volatile nature of that incident, it is nothing new. Perhaps the more alarming actions occurred on January 6, 2021, when the U.S. Capitol was attacked. The motivations for such actions are numerous, but the fact remains that those who participated in that attack were not terrorists but rather extremists.

In a Federal Bureau of Investigations Law Enforcement Bulletin article, “The Seven-Stage Hate Model: The Psychopathology of Hate Groups,” FBI agents (ret.) John Schafer and Joe Navarro discussed begin by stating, “The manifestations of hate are legion, but the hate process itself remains elusive.”6 According to Schafer and Navarro and many other researchers studying hate crimes, there are “three types of bias crime offenders.” They include “thrill-seekers, the reactive offender, and the hard-core offender,” and each has a unique justification, rationale, or technique of neutralization for their actions and hatred.7 The Seven-Stage Hate Model itself includes these steps:

-

- The Group Gathers.

- The Group Defines Itself.

- The Group Disparages the Target.

- The Group Taunts the Target.

- The Group Attacks the Target without Weapons.

- The Group Attacks with Weapons.

- The Group Destroys the Target.

Schafer and Navarro argued that, while hate is a highly complex subject, it is divided into “two general categories: rational and irrational. Unjust acts inspire rational hate. On the other hand, hatred of a person based on race, religion, sexual orientation, ethnicity, or national origin constitutes irrational hate.”8 Yet, the question remains, how does hatred transcend into extremism?

The Center for Strategic & International Studies suggests that far-right extremism is rising in the United States and Europe. The center’s 2018 report, The Rise of Far-Right Extremism in the United States, points specifically to “white supremacists and anti-government extremists, such as militia groups and so-called sovereign citizens interested in plotting attacks against government, racial, religious, and political targets in the United States.” At the same time, the report acknowledges that “violent left-wing groups and individuals also present a threat.”9 Still, right-wing networks are better armed and much larger. One of the interesting things to note about the Center for Strategic & International Studies report ”is that the terms “terrorists,” “terrorism,” “extremists,” and “extremism” are used interchangeably, which may indicate some confusion on the part of policymakers.10

Trends

Extremists from both ends of a spectrum have utilized and encouraged individuals to seek training through various means, which include military training or the recruitment of individuals with previous military experience. According to researchers with the National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism:

From 1990 through 2021, 461 individuals with U.S. military backgrounds committed criminal acts that were motivated by their political, economic, social, or religious goals. Subjects with U.S. military backgrounds represent a small portion (11.5%) of the broader set of extremists who have committed criminal offenses in the United States since 1990. Moreover, the majority (83.7%) of these subjects were no longer serving in the U.S. military when they committed extremist crimes. However, there has been an upward trend in recent cases of criminal extremists with military backgrounds, suggesting that extremism in the ranks may be a growing concern. For example, from 1990-to 2010, an average of 6.9 subjects per year with U.S. military backgrounds committed extremist crimes. Over the last decade, that number has more than quadrupled to 28.7 subjects per year.11

However, statistics generally neglect to point out whether these military individuals are recruited by far-left or far-right organizations.

Theoretical Framework

Social contract theory is based on political philosophy by John Locke, Thomas Hobbes, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, and even many of the United States’ founding fathers. As mentioned earlier, the hypothetical contract entails a compact or agreement between those being ruled and the rulers of definitions such as their rights and duties expressed for both. What the ruled (citizens) expected from the rulers (politicians) are the rights, privileges, and expectations of civil society, such as pursuit of life to live where and how they wanted and their status within society. The rulers’ expectation provides protection and defense for threats, corruption, and crimes against society, providing order. Thomas Jefferson explained the social contract in this way: “When you are alone, you are sovereign, and when you join with others you have to negotiate what is for the commonwealth and negotiate what natural rights you get to keep after adjustment by the government.”12 According to law professor Dr. Anita L. Allen, the social contract is a source of legitimate and consensual authority that “surfaced in constitutional, statutory, and common law cases in this century and the last.”13 Interestingly, “according to some historians, the American colonists relied upon liberal, Lockean notions of a social contract to spirit rebellion against unwanted British rule,” in other words, activism, militancy, radicalism, or violent extremism.14

Within the context of this article, the social contract was broken by government and law enforcement in the political viewpoints of the extremists and, therefore, provides the reasoning for expressing their grievances in a more violent public manner—they feel that the government no longer serves the general welfare of the people and their grievances will not be addressed through the governance of formal redress.

© Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images

Criminal justice professor Dr. Steven Windisch and his colleagues share the descriptive characteristics of the right-wing extremist as espousing ideals that focus on ethnonational, ideological, and religious superiority.15 This includes the belief in racial power over another ethnic group of people and the “need” for racial oversight control, privileged control for the co-existence of a population. The characterization of these beliefs regarding a crime requires the element of violent activity that can influence the behavior of others. On the other side, left-wing extremist ideology includes violent behavior correction of an oppressive system, such as corruption of government relationships with the public.

The mixed ideological differences between right-wing and left-wing beliefs can include members of the criminal justice system and state and federal legislators, such as those who were a part of the January 6, 2021, unlawful occupation of the U.S. Capitol building. The beliefs associated with right- and left-wing ideologies are not a violation of the law if these opinions do not interfere with the exercise of the office holder’s duties. However, caution is to be exercised to minimize conflicts between personal beliefs and the performance as a government representative for a diverse population, according to the United States’ social contract, the U.S. Constitution.

Recommendations

As this article has outlined, violent extremism threats are rising. To address the rise in attacks, law enforcement officers and the intelligence sector must understand the ideologies that influence violent extremism in the United States.

The following list of recommendations includes evidence-based universal solutions that can be utilized to prevent, preempt, disrupt, and mitigate actions (some violent), and respond to those individuals or groups labeled extremists.

-

- Additional civil rights training for law enforcement officers. Law enforcement officers in the United States should fully understand and be able to interpret the U.S. Constitution and the Bill of Rights. The two main amendments that often come into question while on patrol are the First and Fourth Amendments. Society interprets both amendments in their capacity. However, the public’s perception of federal law is not always correct. Therefore, officers must reiterate and support their position when confronting individuals with violations of the First and Fourth Amendments.

For example, police officers have found themselves in verbal and physical altercations with First Amendment auditors. These individuals will stand on a public sidewalk with a video camera and record secure facilities such as police stations, correctional facilities, and other critical infrastructures. When law enforcement approaches the individuals under the act of “appearing suspicious,” the interaction often escalates and becomes violent. The First Amendment auditors’ interpretation of state and federal laws often comes from misinformation and non-relevant sources. As the National Strategy for Countering Terrorism states, “In some cases, “Individuals may develop their idiosyncratic justifications for violence that defy ready categorization.”16

-

- Social media training for law enforcement officers. Law enforcement officers must have annual training in using social media platforms from the perspective of a public official and private member of the public. The importance of this training is to understand how public officials are often targeted on social media for various reasons. Police organizations and, to some extent, officers need to know how to prepare for and respond to verbal attacks that can take place online. Example: A viral video of a law enforcement officer performing an unauthorized arrest is posted on social media. The video immediately gains state or national attention, and that officer, agency, or organization is publicly targeted.

Further, law enforcement officers must receive training that demonstrates how to communicate a message to the community effectively and efficiently. Law enforcement must leverage social media platforms to engage with communities. It is important to have this training because social media is often crowded with a plethora of similar material. It takes knowledge and skills to determine the target audience when posting a social media message. Many third-party organizations conduct this training remotely or in person over a few hours or advanced workshops.

-

- Additional de-escalation training for law enforcement officers. It is important for law enforcement agencies to review and revise de-escalation training for officers consistently. Incidents involving extremists can escalate quickly; therefore, it is imperative to de-escalate incidents and events at the lowest possible level. As criminal justice experts Dr. Charles Russo and Dr. Thomas Rzemyk outlined, “This is done by using proven scientific-based strategies to defuse situations that could lead to violent encounters.”17 One of the best de-escalation training tactics is to utilize role-play scenarios and tabletop exercises. Example: Officers are approached by a loud group while performing security duties at a political rally. The group chants political, racial, and other obscenities at the police officers. A de-escalation tactic that could be utilized is for one of the officers on scene to ask to speak with the group leader and address the issue one-on-one to de-escalate the situation.

-

- Public information cross-training for law enforcement officers. It is important for law enforcement organizations to cross-train all levels of personnel on how to address the media and the public. Officers should be cross-trained at least annually as the roles and responsibilities of public information officers (PIOs) change frequently. Further, officers should be trained to direct certain entities to the designated PIO for the agency or organization. Public and private training opportunities are available for local, county, state, federal, and tribal agencies. For example, law enforcement officers can take the FEMA Public Information Course (IS-29 Public Information Officer Awareness) online via the Emergency Management Institute. Additional advanced-level training is available through FEMA, such as the three-day in-person workshop (E/L0105-Public Information Basics).

-

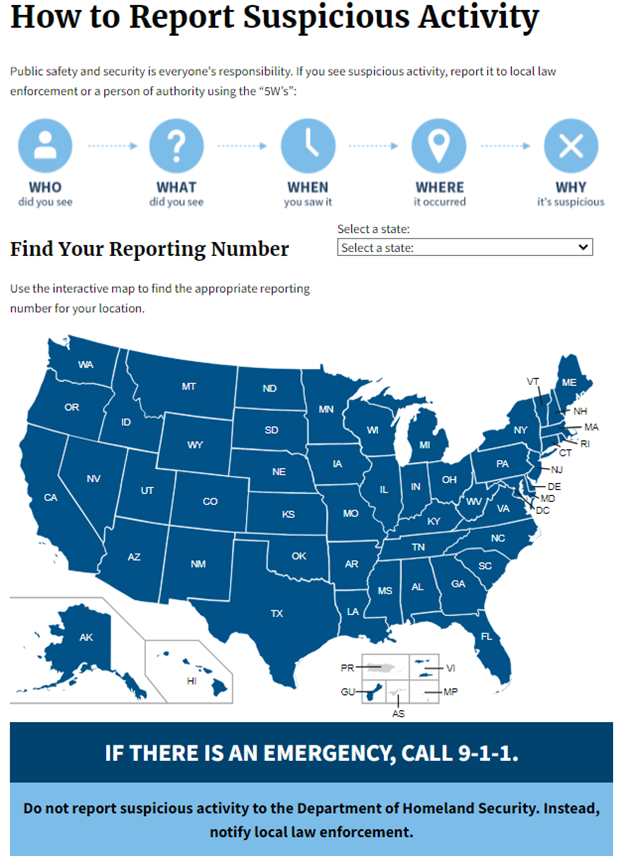

- Additional community awareness, education, and reporting strategies. The public needs to be educated on reporting suspicious activity and violent incidents. Public safety and security are everyone’s responsibility in the United States. All activities should be reported to local, county, state, federal, or tribal law enforcement agencies. Law enforcement agencies should have a clear way to report activity anonymously—online, in-person, via phone, social media, etc. The Department of Homeland Security’s (DHS’s) See Something, Say Something campaign is a great example of how to educate the public on reporting suspicious activity to law enforcement agencies. The DHS states that the 5 Ws (who, what, when, where, and why) should be used when reporting incidents. Images such as the one from DHS’s website can easily be added to websites and other platforms for community members to report activity.

|

| (Source: Department of Homeland Security, “How to Report Suspicious Activity,” 2021.) |

-

- Additional psychological, sociological, and behavioral health training for law enforcement officers. Many law enforcement professionals must take academic courses such as psychology, sociology, and criminology as part of their formal education to become POST-certified officers. It is vital to readdress and retrain officers on some of the concepts learned in these courses. Additional training within the agency will reinstate the modus operandi and additional motives that individuals and extremists use to carry out violent acts. Additionally, this type of training will further prepare officers to respond to individuals who exhibit problematic behaviors due to a mental health condition.

-

- Revisit law enforcement training academy entry standards and practices for mental health. As the ideologies change for violent extremists, all incoming law enforcement officers must be psychologically screened. Additional in-depth medical and mental health screenings should take place to ensure that incoming law enforcement officers can handle the emerging and changing trends within policing today. The role of policing has changed drastically over the past five to ten years as incidents have gotten more physical and violent. Therefore, it is crucial to ensure incoming candidates’ mental safety and security. This can be done through additional screenings, interviews, and testing with trained mental health professionals.

Conclusion

Extremism is subjective and often politicized, which makes it difficult for law enforcement and intelligence professionals to label an individual or group an extremist while they could be a mere protest movement, or on the other end of the spectrum, a terrorist element. Violent extremism threats are rising for law enforcement agencies across the United States. This article has outlined seven key evidence-based strategies that can assist law enforcement organizations through resiliency and reactionary-based planning. It is essential for public safety leadership to check in with law enforcement personnel on a periodic and frequent basis, such as roll call or in-service training to ensure that officers are mentally, physically, and behaviorally attuned to the changing public safety environment.

Additionally, there are indications that additional community policing efforts can be utilized to counter violent extremism in policing. Creating trusting relationships with the public allows law enforcement organizations to use strategies such as innovative communication to establish further transparency and collaboration with all stakeholders. Furthermore, continued collaborative efforts between fusion centers and task forces (federal and state entities) should be encouraged at all levels, especially when faced with possible protests of any kind. Understanding who are the agitators are and their motivation are essential for intervention; preemption; and if needed, de-escalation. 🛡

The views and opinions expressed are the author(s) and not that of any U.S. government agency.

Charles T. Kelly Jr., PhD, is a professor at Columbia Southern University. He spent 37 years in law enforcement, retiring in 2011 as major and confidential assistant to the chief deputy. He holds a PhD in the Administration of Justice from the University of Southern Mississippi, a master’s degree in criminal justice from the University of Alabama, a master’s degree in cybersecurity policy from the University of Maryland, and a master’s degree in national security from American Military University. He is a recognized expert in police policy and procedure and use of force in United States federal district courts in Louisiana (Eastern, Middle, and Western Districts) and several state courts in Louisiana. Charles T. Kelly Jr., PhD, is a professor at Columbia Southern University. He spent 37 years in law enforcement, retiring in 2011 as major and confidential assistant to the chief deputy. He holds a PhD in the Administration of Justice from the University of Southern Mississippi, a master’s degree in criminal justice from the University of Alabama, a master’s degree in cybersecurity policy from the University of Maryland, and a master’s degree in national security from American Military University. He is a recognized expert in police policy and procedure and use of force in United States federal district courts in Louisiana (Eastern, Middle, and Western Districts) and several state courts in Louisiana. |

Mark Logan, PhD, is a 37-year law enforcement professional with a career that includes 8 years as a Detroit, Michigan, Police Officer, and 27 years with the U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives, retiring as an assistant director. Logan is a lead faculty for graduate criminal justice programs at Columbia Southern University and has worked in various instruction and leadership positions in higher education for approximately 12 years. He currently enjoys active memberships in various criminal justice support and research organizations and is a life member of the IACP. Mark Logan, PhD, is a 37-year law enforcement professional with a career that includes 8 years as a Detroit, Michigan, Police Officer, and 27 years with the U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives, retiring as an assistant director. Logan is a lead faculty for graduate criminal justice programs at Columbia Southern University and has worked in various instruction and leadership positions in higher education for approximately 12 years. He currently enjoys active memberships in various criminal justice support and research organizations and is a life member of the IACP. |

Charles M. Russo, PhD, is a professor at Columbia Southern University, American Military University, and St. John’s University. He is a veteran U.S. Navy intelligence specialist and a former intelligence analyst of the FBI, and he has more than 30 years of experience in intelligence and counterterrorism analysis. The former associate dean of intelligence management for National American University’s Henley-Putnam School of Strategic Security, he is recognized as an intelligence analysis scholar and terrorism expert. He holds the DoD Intelligence Fundamentals Professional Certification and the ODNI’s Intelligence Community Advanced Analyst Program (ICAAP) certification and is the recipient of numerous scholarly and professional awards. Charles M. Russo, PhD, is a professor at Columbia Southern University, American Military University, and St. John’s University. He is a veteran U.S. Navy intelligence specialist and a former intelligence analyst of the FBI, and he has more than 30 years of experience in intelligence and counterterrorism analysis. The former associate dean of intelligence management for National American University’s Henley-Putnam School of Strategic Security, he is recognized as an intelligence analysis scholar and terrorism expert. He holds the DoD Intelligence Fundamentals Professional Certification and the ODNI’s Intelligence Community Advanced Analyst Program (ICAAP) certification and is the recipient of numerous scholarly and professional awards. |

Thomas J. Rzemyk, EdD, is a professor at Columbia Southern University. He is a researcher and expert in cybersecurity, criminal justice, homeland security, and counterterrorism. He has worked in public and private education for approximately 15 years. He holds a Certified Homeland Protection Professional (CHPP) certification and the Certified Anti-Terrorism Specialist (CAS) certification. Thomas J. Rzemyk, EdD, is a professor at Columbia Southern University. He is a researcher and expert in cybersecurity, criminal justice, homeland security, and counterterrorism. He has worked in public and private education for approximately 15 years. He holds a Certified Homeland Protection Professional (CHPP) certification and the Certified Anti-Terrorism Specialist (CAS) certification. |

Notes:

1Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, s.v. “Social Contract Theory.”

2FBI, “Domestic Terrorism: Definitions, Terminology, and Methodology,” 2020; 18 U.S.C. 2331(5).

3Eric Swalwell and R. Kyle Alagood, “Homeland Security Twenty Years After 9/11: Addressing Evolving Threats,” Harvard Journal on Legislation 58, no. 2 (2021): 228.

4Swalwell and Alagood, “Homeland Security Twenty Years After 9/11,” 244.

5Michael A. Jensen, Elizabeth Yates, and Sheehan Kane, Radicalization in the Ranks: An Assessment of the Scope and Nature of Criminal Extremism in the United States Military (National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Response to Terrorism, University of Maryland, 2021).

6John R. Schafer and Joe Navarro, “Seven-Stage Hate Model: The Psychopathology of Hate Groups,” FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin Volume 72, no. 3 (March 2003): 1.

7Schafer and Navarro, “Seven Stage Hate Model,” 3.

8Schafer and Navarro, “Seven Stage Hate Model,” 1.

9Seth G. Jones, The Rise of Far-Right Extremism in the United States (Center for Strategic & International Studies, 2018): 1.

10Jones, The Rise of Far-Right Extremism in the United States.

11Jensen, Yates, and Kane, Radicalization in the Ranks.

12Clay S. Jenkinson, “What Would Jefferson Do?” The Thomas Jefferson Hour.

13Anita L. Allen, “Social Contract Theory in American Case Law,” Florida Law Review 51, no. 1 (January 1999): 5.

14Allen, “Social Contract Theory in American Case Law,” 3.

15Steven Windisch, Gina Scott Ligon, and Pete Simi, “Organizational [Dis]trust: Comparing Disengagement Among Former Left-Wing and Right-Wing Violent Extremists,” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 42, no. 6 (December 2017): 556–580.

16The White House, National Strategy for Countering Domestic Terrorism (Washington, DC: Executive Office of the President, National Security Council, 2021).

17Charles Russo and Thomas Rzemyk, “Finding Equity, Inclusion, and Diversity in Policing,” Police Chief Online, August 4, 2021.

Please cite as

Charles Kelly et al., “Violent Extremism and the Social Contract Theory,” Police Chief Online, July 21, 2022.