For many years, the criminal justice community has relied on latent fingerprints to identify perpetrators of crimes. More recently, advancements in technology have allowed palm prints to also be used for identification purposes, adding to agencies’ crime-solving arsenals. It is estimated that 30 percent of latent prints found at crime scenes come from palms.1 That estimate is not surprising when one considers the amount of surface on a palm compared to that of a fingerprint. The larger surface area also provides more characteristics for comparison. A fingerprint can have 150 characteristics versus about 1,500 on a palm print.2 However, for this evidence to be of use, agencies must ensure they capture palm prints correctly during booking. The quality of the palm prints is important, as it is with fingerprints.

The National Palm Print System

When the FBI launched the National Palm Print System (NPPS) on May 5, 2013, it dramatically expanded investigators’ access to palm prints, which were previously stored within individual federal, state, local, and tribal law enforcement agencies’ databases.3 The NPPS is part of the FBI’s Next Generation Identification (NGI) System, and it serves as a virtual storage facility of palm print images and the identities of those to whom they belong. This national database is a central resource for any agency to come to look for an offender’s identity against a national biometric repository of event-based criminal, civil, and unsolved latent biometrics. Agencies can submit palm prints found at crime scenes to the NPPS to see if matching prints are on record within the NGI System. Currently, the NPPS maintains more than 20 million unique palm print identities and more than 42 million individual palm print images tied to those identities, all of which are available for investigative leads. In addition, the NGI’s Unsolved Latent File (ULF) consists of a variety of unsolved latent prints previously searched through the NGI System whose owners have not yet been identified.

Since the NPPS’s deployment in 2013, many U.S. police agencies are now submitting palm print images. Currently, 48 states along with agencies in Washington, DC; Guam; and Puerto Rico submit palm prints to the NPPS. Participating agencies have reported numerous successful outcomes directly related to palm print matches. The following are two examples of cases solved with the help of the NPPS.

The FBI conducts a Biometric Identification Award program to recognize major violent crime cases that are solved with NGI. One prime example is how the Las Vegas Metropolitan Police Department won the 2018 Biometric Identification Award for identifying a suspect with assistance from a palm print match from the NPPS (see sidebar). An informative video about this case and others can be found on the FBI’s Biometric Identification Awards webpage.4

|

NPPS Success Stories Moore, Oklahoma In June 2012, a 44-year-old man’s body was discovered lying in his driveway in Moore, Oklahoma. The only evidence found at the scene was a pair of palm prints on a truck near the body. Investigators collected the palm print images and searched them through the Oklahoma State Bureau of Identification’s (OSBI’s) Automated Fingerprint Identification System, but no match was found. No national palm print database existed at the time, and authorities were unable to identify whom the palm prints belonged to. The case stalled due to lack of information. Shortly after the NPPS’s deployment in 2013, the OSBI began a special project to review cold cases for unidentified latent prints suitable for a search through NGI. In February 2014, the OSBI ran the palm prints from the 2012 case in Moore, Oklahoma, through NGI. After finding no matches, the OSBI added the palm prints to NGI’s ULF. In March 2016, a criminalist from the OSBI’s Latent Evidence Unit received an Unsolved Latent Match notification on the submitted latent palm prints, so she requested palm prints from the Criminal Justice Information Services (CJIS) Division. A senior criminalist compared the palm prints from the crime scene to the ones stored in the NPPS and identified the subject they belonged to. When authorities contacted the subject—who was living in Texas—he eventually admitted that on the day of the incident, he had driven his roommate to the house belonging to the roommate’s mother in Oklahoma. The two men encountered the roommate’s stepfather, and they began to physically fight. At this point in the story, details vary, but the stepfather ended up dead in the driveway. The medical examiner determined the victim died from blunt force trauma injuries and possible asphyxia due to an assault. Now, police had the name of two suspects in the case. They arrested the roommate on September 8, 2016, and the subject turned himself in to the police days later. The only forensic evidence was the palm prints from the scene. Prosecutors dismissed the charges for the roommate in February 2017, but in January 2018, the subject was found guilty of one count of First-Degree Manslaughter for his role in the victim’s death. Las Vegas, Nevada In November 2016, the Las Vegas Metropolitan Police Department (LVMPD) began investigating an incident involving an elderly female victim. She lived alone and was sleeping in her apartment when an individual pried open her bathroom window and entered her home. The suspect went to the woman’s bedroom and attempted to sexually assault her. The woman resisted until the suspect gave up on the assault and demanded money instead. The victim gave the suspect $26, and he fled through the front door. During the attack, the woman sustained injuries to her mouth, arms, and back. Detectives investigated the incident until they exhausted all leads. The only possibility for identifying the suspect rested on the analysis of several latent palm prints discovered on the victim’s bathroom windowsill. A search of the LVMPD database produced no matches, so detectives initiated a search through the NGI System. NGI returned a match, and detectives learned the identity of the suspect within 24 hours of the crime. Two days later, authorities took the suspect into custody and charged him with Attempted Sexual Assault, Robbery, Burglary, and Battery to Commit Sexual Assault. In January 2017, the suspect pled guilty to a felony charge of Attempted Sexual Assault and was required to register as a sex offender. He was sentenced to 8 to 20 years in the Nevada Department of Corrections and lifetime supervision. |

The Cost of Incomplete Palm Print Images

Unfortunately, not all palm prints submitted by state agencies make it into the NPPS. Currently, 18 state agencies submitting to the federal database have less than an 80 percent enrollment rate with 6 of the agencies having less than 50 percent of their palm prints enrolled. The reason is simple: if a subject’s palm print images are not correctly and clearly captured during the booking process, print examiners cannot distinguish important details in the prints. Thus, as Scott Rago, chief over the FBI’s biometric services, says, “Storing the images is pointless, and they are rejected for submission into the NPPS.”5

Palm prints submitted to the NPPS that do not meet the enrollment standard will not have an opportunity to be searched against records in the ULF. This results in a failure to identify potential suspects and, subsequently, fewer solved crimes. It is impossible to estimate the number of criminal investigations these failed palm print enrollments affect, but when one considers there are more than 850,000 records currently housed in the ULF, with more than 25,000 unknown latent prints processed through the national system monthly, prospective matches are most certainly being missed.

The following scenario is fictional but serves as an example of how unacceptable palm print images can thwart crime-solving efforts.

In November 2017, a body was discovered in an abandoned vehicle parked next to a state park. The victim, a 34-year-old female, was apparently strangled and left in a vehicle that was registered in her name. Little physical evidence was found at the crime scene; however, evidence technicians from the local police department (PD) discovered a palm print on the vehicle and searched it through the national and state databases. Investigators did not identify any matches and exhausted all other leads. No other evidence was found, and the case stalled.

Six months after the unsolved homicide—and more than 400 miles away—a deputy sheriff conducted a traffic stop on an individual whose car had an expired registration. During the traffic stop, the subject was found to be breaking multiple laws, so he was arrested and charged with multiple offenses, including drug violations, and was subsequently held at the local jail. During the booking process, officers captured the offender’s palm prints and submitted them to the NPPS. Unfortunately, the offender’s palm prints were not properly captured, so the palm print images were unable to be enrolled or searched against the unsolved latent prints in the national system.

Had the subject’s palm prints been captured correctly, the NPPS would have notified the police department that the palm prints of the person arrested by the sheriff’s office matched the latent palm prints from the homicide they were investigating. Due to the improperly captured palm prints, the cold case would remain unsolved. Unfortunately, this type of scenario occurs too often, causing crimes to remain unsolved.

Capturing a Quality Palm Print

It is well-known among law enforcement personnel that the booking process—paperwork and capturing a subject’s prints—adds to an already long, busy day. These duties become even more challenging when the subject is uncooperative. However, it is important to remember that more than 18,000 federal, state, local, and tribal law enforcement agencies rely on the completeness and accuracy of the information submitted to the NPPS, and it all begins at the booking station. A few extra moments spent capturing the prints could be the difference between identifying a suspect in an investigation or letting that suspect escape justice. It is worth the time to learn what makes complete and acceptable palm print captures.

Parts of the Palm

|

|

|

|

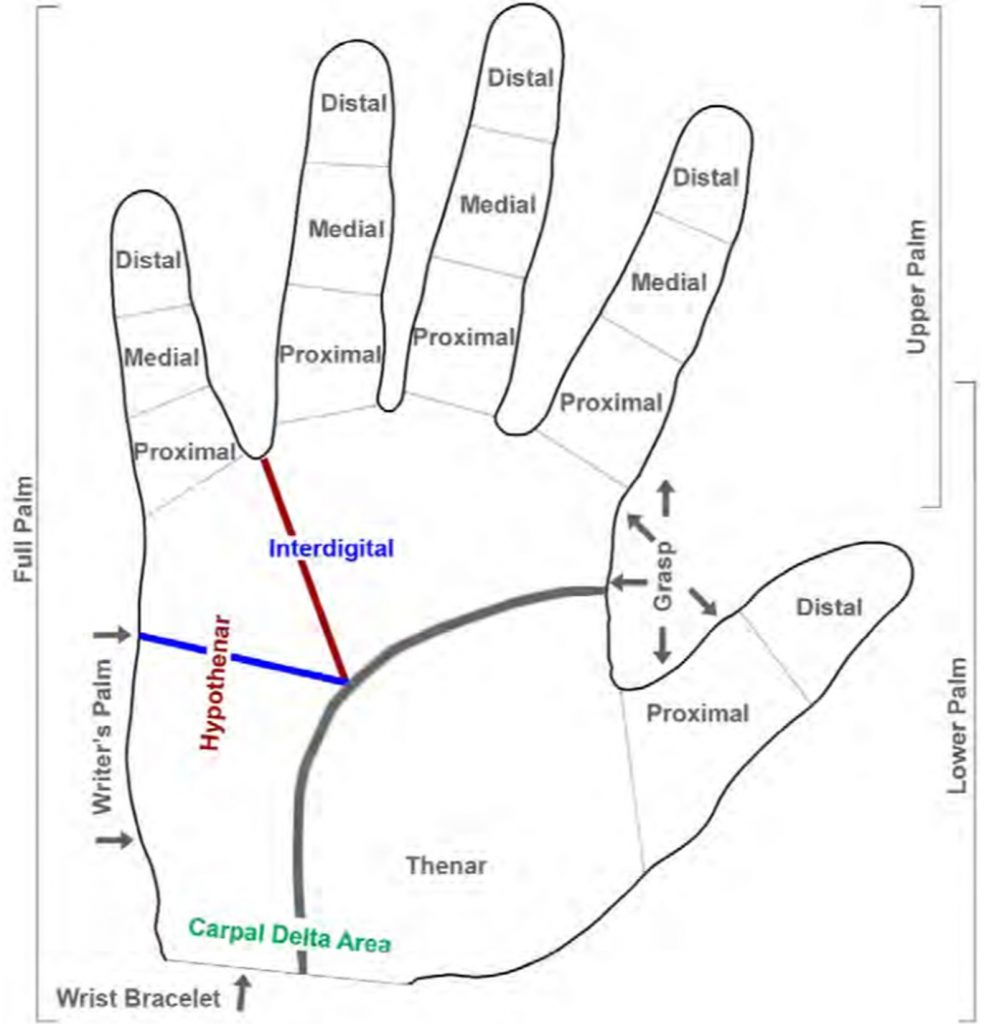

The entire area of the full palm is defined as the area extending from the top of the wrist bracelet to the tips of the fingers. The types of equipment to capture palm prints vary, but there are two accepted ways to properly capture full palm prints: four-scanned images or six-scanned images. The ultimate goal is that the fingerprint images can be linked to the palm print images, establishing a complete subject identity.

Four-image capture of palm prints. A four-image capture of palm prints includes the full left and right palm prints (essentially two full hands) and the corresponding left and right writer’s palms (the outside edges of the hands).

Six-image capture of palm prints. The six-image capture includes the upper image and lower image from each hand with the corresponding left and right writer’s palms for a total of six images. The lower image should extend from the wrist bracelet to the top of the first finger joint (interdigital area or proximal finger joint) and should include the thenar and hypothenar areas of the palms. The upper image should extend from the bottom of the interdigital area to the upper tips of the fingers.

The combination of the lower and upper images provides an adequate amount of overlap in the middle of the images to make up one complete palm print belonging to the same person. Examiners accomplish this by matching the ridge structures and details contained in the common interdigital areas of both images. When finger impressions are captured in the upper image, examiners can match the palm print to a ten-print record (which includes 10 fingerprint images) and further confirm the subject’s identity.

What Makes a Quality Capture?

As with other biometrics, palm print image quality directly impacts system algorithm performance. This is true of both the initial image enrolled into the NPPS as well as the image collected for search against that repository at a later date. Insufficient ridge detail, dark spots or smudges on the images, and residue on the collection equipment can all lead to poor quality prints that cannot be added to the NPPS. However, according to analysts working in the Biometric Identification and Analysis Unit’s Palm Services and Analytical Team at the FBI’s CJIS Division, the overwhelming cause for non-enrollment is the lack of distal images (images of the fingers’ top joints to include the fingerprint areas) submitted with the palm print images.

The FBI has a good explanation for why agencies need to submit distal images. When palm prints are submitted to the national database, they must be validated to ensure they match the identities of the individuals with the ten-print records. The segmentation software in the NGI System that the NPPS uses requires at least one fingerprint from each hand to perform an automated system validation. Palm prints that do not enroll might not have all ten distal images present in the upper palm prints or full palm print areas, causing the submissions to fail.

When law enforcement agencies are unaware of the NPPS’s validation process, they could improperly capture palm print images, resulting in the images’ rejection. According to the FBI, in some cases, agencies do not possess the appropriate equipment to capture palm prints correctly. However, the primary cause of NPPS rejection is lack of training for those who capture palm prints during the booking process.

Resource to Improve Palm Print Capture

To support their partner agencies and ensure the NPPS has a gallery of high-quality known palm prints, the FBI is proactively working with state submitting agencies to correct these capture issues. The FBI has posted helpful guides to enhance users’ understanding of palm anatomy and provide a practical look at best practices for image captures. The FBI has published a Palm Print Capture Guide online.6 Users can also find an informational palm print poster.7 Law enforcement agencies can use the best practices guide and poster as reference tools for correctly capturing palm print images. In addition, agencies can find a link to a Recording Friction Ridges eLearning module.8

The NPPS will continue to expand and provide a reliable investigative resource for law enforcement agencies. As the size of the NPPS continues to grow, so too will the system’s utility to the criminal justice community.

Notes:

:1Ron Smith, “Advanced Palmprint Comparison Techniques” (presentation, International Association for Identification, Virginia Beach, VA, March 30, 2009).

2FBI, Recording Friction Ridges, (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, 2020).

3FBI, “National Palm Print System Repository Available for Law Enforcement Access,” CJIS Link, April 30, 2019.

4FBI, Biometric Identification Awards, videos, U.S. Department of Justice.

5Scott A. Rago (section chief, Criminal Justice Information Services, FBI), email to author, May 14, 2020.

6FBI, A Practical Guide for Palm Print Capture (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, 2019).

7 FBI, “Palm Print Capture,” poster, U.S. Department of Justice, 2019.

8 FBI, Recording Friction Ridges.

Please cite as

Gary Williams, “What Police Officers Need to Know About Palm Prints,” Police Chief online, December 9, 2020.