Today’s environment in policing is fast moving and very challenging: tightened budgets, less interest among young adults in becoming police officers than in the past, and a turbulent atmosphere that makes for a difficult staffing and succession situation. With less of a pipeline behind them and higher rates of retirement and other transitions, officers may wonder if they want to continue in the profession—let alone seek a promotion or even become a chief someday.

Supervisors and law enforcement executives certainly have their hands full with what is right in front of them. But a key question in regard to recruitment, retention, and succession planning for agencies is “What can we do right now?” While there are many available options for departments, municipalities, states, and counties, there is one that can be implemented right away, at little cost to start, and that could be a very important way to continually attract and engage staff at all levels: individual development plans (IDPs).

What Is an IDP?

An IDP is a written summary of personal and professional goals, objectives, and interests and includes a series of potential options to incrementally achieve those goals through training, reading, and experiences. The IDP maps out potential areas to explore through a variety of developmental activities and processes, all with the understanding that, to maximize each activity, some thought will be required—in the beginning, but also reflection throughout, and especially at the end of the activity. Individuals should come away from each developmental activity, course, or book with a different perspective, idea, or action that they can implement. IDPs are like creating a menu of leadership, technical, or personal growth options.

Development plans are common for executive-level staff, such as chiefs, commanders, or senior civilians. However, IDPs can actually be used for anyone in the agency, regardless of title or role and regardless of whether they aspire to a command position. For example, a state crime lab analyst may want to deepen his or her expertise in a criminal forensic science area; an IDP would enable the individual to discuss these interests with a supervisor, formulate some options to develop that expertise (both independently and through work at the agency), and then have periodic progress checks.

IDPs for Recruitment

IDPs can be a valuable way to attract new recruits to the profession by showing that the agency is interested in employees’ futures as law enforcement officers. There are many opportunities to take on new assignments, roles, and responsibilities and to seek challenges, even in a small department. By having a wider variety of experiences, an officer is better positioned to fill any future vacancy that arises, whether supervisory, command, or even in a technical area (such as becoming a firearms instructor). IDPs can be used as a recruiting tool to show a roadmap, path, or the slew of options available once recruits enter the agency and graduate from their basic academy course.

IDPs for Retention and Succession Planning

Similarly, IDPs are vital to the retention of staff and developing future leaders of the organization. Chief Randy S. Bratton states, “preparing and developing staff not only encourages retention, but encourages the professional development of agency staff and the quality of the agency as a whole.”1 Researchers studying IDPs in police agencies also noted their use as a promising practice, pointing out that “[IDPs] give a voice to the employee, provides clear parameters to follow, and, if done correctly [by supervisors and the agency], fosters a relationship of mutual respect.”2 IDPs can help emerging leaders understand how they can get to the next level in their careers, and they provide the path to move forward. Ultimately, IDPs give ownership to the employees to help them on their professional journeys.

Leading the Way

Each agency is unique and can tailor the IDP process to its own needs and circumstances. An agency does not need a long, drawn-out policy to be written on IDPs—it can be as simple as an annual letter from the chief laying out some of the principles and practices outlined in this article and encouraging everyone to start the process. Supervisors must be integrally involved in the IDP process as well, since they’ll be working directly with their staff on it—and they should also be preparing IDPs for themselves.

Each agency is unique and can tailor the IDP process to its own needs and circumstances. An agency does not need a long, drawn-out policy to be written on IDPs—it can be as simple as an annual letter from the chief laying out some of the principles and practices outlined in this article and encouraging everyone to start the process. Supervisors must be integrally involved in the IDP process as well, since they’ll be working directly with their staff on it—and they should also be preparing IDPs for themselves.

Senior leaders must model the use of IDPs and openly discuss the process. Every chief should have an IDP throughout his or her career. The IDP process can be very helpful in career planning, even for a seasoned veteran. Investing time in this process can be especially helpful, as an IDP will be a source of stability for leaders who find themselves in the midst of political sea changes, organizational crises, or other unexpected situations.3

IDP Process

The process to write an IDP is a four-step process:

- Self-Reflection

- Discuss and Explore

- Draft

- Revise and Revisit

| Self-Reflection | Discuss/Explore | Draft the IDP | Revise/Revisit |

|

|

|

|

Start with a Question

Starting the IDP process with the question “What do I want?” is a useful way to kick off this reflection, but it can’t be the ending point. An IDP is never done in isolation—it involves many different people, especially the employee’s supervisor. A supervisor can also support this reflection. As Dr. Warren Bennis points out in his classic leadership text, “Reflection may be the pivotal way we learn. [Reflection includes] looking back, thinking back, dreaming, journaling, talking it out, watching last week’s game, asking for critiques, going on retreats—even telling jokes.”4 These all help one process his or her thoughts and engage the creativity necessary to think long term.

The role of a supervisor is to assist in asking a follow-up question: “What does the team need?” They are in a unique position to understand the organization, its dynamics, and the possibilities. Supervisors are essential in the IDP process because they are best positioned to see how an individual’s developmental needs may fit into the agency’s strategy, mission, vision, and departmental priorities. A strong supervisory relationship is also essential to support the development process, both formally and informally, as well as advocate to senior management on behalf of the team.

Supervisors can also cultivate a culture of development in their team. As Dr. Bennis noted above, individuals find inspiration, energy, and ideas from everyday encounters; supervisors can support shift or operational debriefs for 5–10 minutes at the end of the day to enhance this discovery process. Sharing best practices or lessons learned is another useful way to incorporate learning and development into a team. Finally, encouraging and supporting the IDP process is an essential function of a supervisor.

As people start to really think about where they are, where they want to be, and how they might get there, they can begin to envision a future state. Then, one can build his or her IDP to start the process of getting there. But first, the individual needs to start writing ideas down and exploring, discussing, and reflecting some more.

Writing It Down

A written IDP provides the common ground to initiate and continue discussions among supervisors, mentors, peers, and executives. Writing it down can also be good for obtaining commitment, having a clear understanding, and identifying specific milestones that can be accomplished. A written plan also gives everyone a baseline of what has been contemplated or completed year to year, since a historical review can also inform future development discussions. This may be especially important if budget or time constraints disallow some development goals to be completed; they can be transferred to the next cycle.

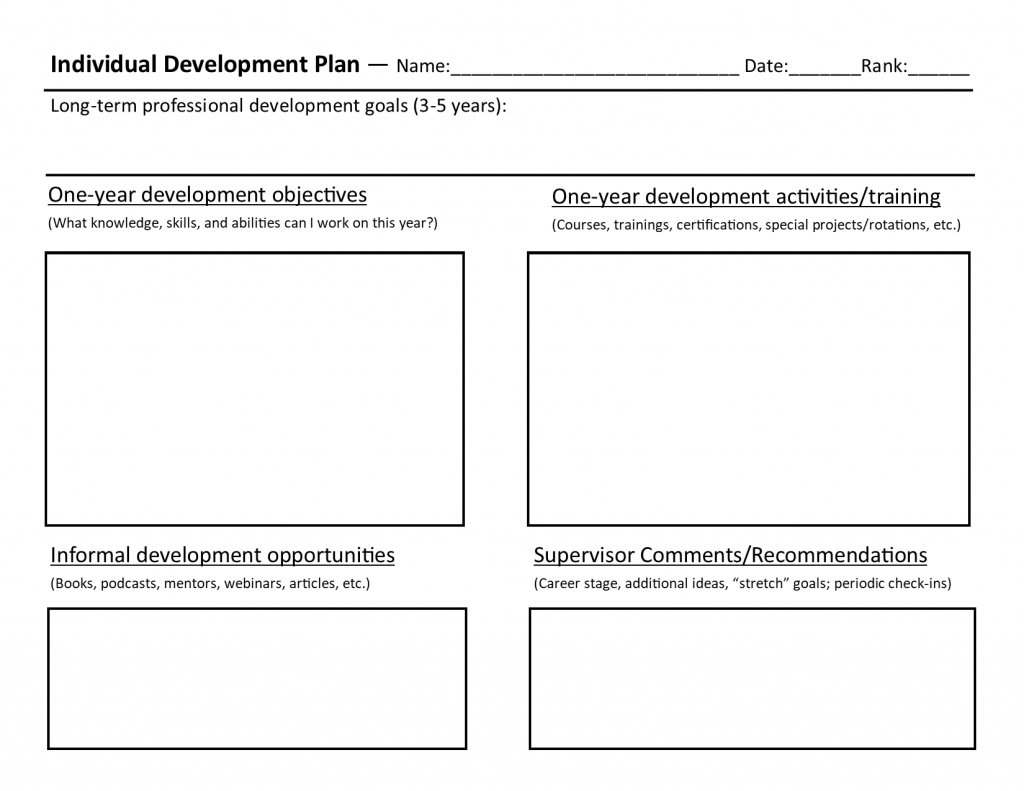

While the specific form or format is not as important as the reflection and exploration phases, many IDPs use a goal/activity square that can be filled in. Figure 1 is an example; it has a long-term goal statement (generally within the next 3–5 years), along with two squares below that describe the knowledge, skills, and abilities the person is seeking to obtain, enhance, or refresh over the next 12 months. Finally, the developmental activities occupy the next square. Other forms may include informal development (sometimes called self-development), which may include books, podcasts, or other activities. Examples of IDP forms and guides can be found online very easily.5

Knowledge, Skills, and Experiences

IDPs can cover three areas: knowledge, skills, and experiences. Knowledge encompasses those fundamental facts and theories that govern a particular area, such as communication or leadership. Skills are practical applications, procedures, and capabilities needed to complete a task or series of tasks. Experiences are those lived actions and immersive events that people actually go through. All three are important to include in an IDP.

Knowledge is the human, social, and procedural tasks and baseline educational information required to do a job. This includes topics that are taught in basic academy classes, or advanced classes to advance into a specialized role, such as dispatch, homicide detective, SWAT team, or animal control. Often, these are taught both on-the-job, but also in course settings or in-service training.

Skills are the abilities to perform and execute specific actions. Skills may include things like clearing a house during a search warrant, conducting an interview of a subject, making a traffic stop, or conducting surveillance. Skills in leadership are especially important and include communication, strategic thinking, decision-making, public speaking, and other competencies that are used every day in leadership roles and responsibilities.

Finally, experiences are events, lived practical encounters, observations of others. Experiences are foundational to our ability to excel. This is why scenarios, problem-based learning, simulations, and the like are so important. In a law enforcement context, these may include acting supervisory assignments, details to a task force or other agency, shadowing a senior executive and debriefing him or her after, or any number of other experiences. (See the sidebar for additional examples).

The process of crafting an IDP should include consideration of all three categories, especially the experience component. While formal training is very helpful, having the actual experience is often where we learn and grow the most.

Moving Forward: Exploring the Options

To achieve the IDP objectives, regardless of timeframe, the employee can incorporate specific developmental activities into their responsibilities or work time. These can include things like developmental assignments, details, formal training courses, conferences, college degrees or certificates, and special projects. They can also be informal development activities, such as reading professional books (or joining a book club), joining a professional association, listening to podcasts, attending webinars, or having a mentor. (See the sidebar for a list of potential activities.)

Possible Developmental Options |

|

|

|

In the late 1980s, the Center for Creative Leadership (CCL), a nonprofit research training and center identified the concept of “development in place.”6 Development in place is the idea that experience can be the best learning device (instead of, for example, a training course). For example, a civilian records clerk who is interesting in becoming an intelligence analyst can, with the support of the supervisors, begin to “intern” one day a week with the analytical team and provide support. A patrol officer may also want to broaden his or her competencies and begin to look at becoming a sergeant; he or she would start taking on more leadership roles in the squad.

There are numerous possibilities, but the CCL researchers found there were two main types of development in place:

- challenge-driven assignments—“stretch” opportunities to help broaden leaders

- competency-driven assignments—target the acquisition, or enhancement, of specific skills7

For both, generating possible ideas; asking for suggestions from peers, colleagues, mentors, or supervisors; and considering additional responsibilities or situations that would allow one to practice key skills are all important considerations.8

Exploring the developmental options is just as important as the self-reflection portion of the IDP process. One of the most interesting components is to identify what opportunities are out there and how they may fit a person’s specific needs. Some options are going to require an investment of funds, some courses may not align with the schedule, and some options require an intense application process. But, not every development option needs to be a training course or conference or require an expensive outlay of funds. Being creative is important; much like reflection, exploring can also open new opportunities, options, and possibilities that had not been previously considered.

Maximizing the Developmental Experience

The IDP is the first step in a cycle of acting, thinking, and responding to build a diverse and deep career as a law enforcement professional and leader. Once a developmental activity is in progress—and once again, when fully completed—it’s essential to reflect, process, and evaluate the experience. This will feed forward ideas, discoveries, or insights that will help as the next IDP is built.

The actual “what” is done is less important than the process of what one has learned. As one researcher found, treating an IDP as a “’living process’ of reading, thinking, comparing, analyzing, puzzling, and constantly questioning” will deliver more robust results long-term because of the cognitive processes that it stimulates.9

Another group of researchers, several of whom taught at the U.S. Air Force Academy, described three questions (called the AOR Model) to support this process of thinking and analyzing:

- Action: What happened? What specifically did you do (or not do) in the event?

- Observation: What were the results? Did they have the intended impact? How were others affected?

- Reflection: How has this landed? What could you do differently looking back? What did you learn?10

They note that less effective leaders don’t take the time to systematically and repeatedly step through this reflection process, which lessens the impact or ability to improve. “Leadership development through experience may be better understood as the growth resulting from repeated movements through the [AOR Model] rather than merely in terms of some objective dimension,” such as a single IDP activity.11 This underscores the importance of taking a long-term approach to one’s own development and supporting the development of others.

Special Considerations

Older officers who are contemplating or nearing retirement can still participate in an IDP process. For them, it may be less about training to take, but rather what training they can give. Knowledge transfer in a structured way is a great way to instill a legacy. They can also be mentors to other officers. In addition, they can use the IDP process to consider how they will spend their post-retirement years. While it may not directly benefit the agency, hopefully, it will cause officers to think about how they may continue to contribute as they enter into their next phase of life.

Some people may hesitate to complete an IDP for a variety of reasons, including feeling like they may “lock themselves in” to a specific path or for fear of the perception of “measuring the drapes” (i.e., looking too far forward). These concerns can be alleviated with some basic principles: first, the IDP is always subject to revision, based on the changing circumstances; second, it is a plan that is worked on together, so it can be realistic and based on balancing the needs of the agency and the desires of the individual; and third, it is one of many development, training, personnel, and performance tools available to the agency, not the “one and only” tool. It’s also a good reminder that the IDP is not a guarantee that someone will automatically obtain a specific promotion, desired course, or plum assignment—the IDP is only a guide to help get people somewhere beyond where they are currently.

Conclusion

Leaders must be modeling the way by sharing their time and perspective on development. This is ultimately how the profession will recruit, retain, generate, and mature the next generation of leaders. The value of developmental plans is well-documented, and IDPs provide voice, vision, and action for the work to be done. Many agencies are highlighting specific goals in their strategic plans around personnel recruitment, retention, leadership development, and succession planning. By ensuring the chief and the command staff, supervisors, and civilians are consistently doing IDPs; sharing what they have learned; and encouraging others to think, plan, and act, agencies will be better positioned to weather many of the storms the profession is currently facing or may face in the future. Employee development through IDPs is one of the best investments of a leader’s time. d

Notes:

1Randy S. Bratton, “Succession Planning and Staff Development,” Big Ideas for Smaller Police Departments (Fall 2008): 1–5.

2Shannon Branly et al., Implementing a Comprehensive Performance Management Approach in Community Policing Organizations: An Executive Guidebook(Washington, DC: Office of Community Oriented Policing Services, 2015), 47.

3Chapter 2: How Police Chiefs and Sheriffs Are Finding Meaning and Purpose In the Next Stage of Their Careers (Washington, DC: Police Executive Research Forum, 2019).

4Warren Bennis, On Becoming a Leader (Philadelphia, PA: Basic Books, 2009).

5See, for example: Madison (WI) IDP Guide; Office of Personnel Management, IDP resource page; King County (WA) IDP Sample.

6Michael M. Lombardo and Robert W. Eichinger, Eighty-Eight Assignments For Development In Place: Enhancing The Developmental Challenge of Existing Jobs (Greensboro, NC: Center for Creative Leadership, 1999).

7Cynthia D. McCauley, Developmental Assignments: Creating Learning Experiences Without Changing Jobs (Greensboro, NC: Center for Creative Leadership, 2006), 11–12.

8McCauley, Developmental Assignments, 13–14.

9Robert J. Thomas, Crucibles of Leadership: How to Learn from Experience to Become a Great Leader (Boston, MA: Harvard Business Review Press, 2008), 79,

10Richard L. Hughes, Robert C. Ginnett, and Gordon J. Curphy, Leadership: Enhancing the Lessons of Experience, 8th ed. (Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill Education, 2015), 46.

11Hughes, Ginnett, and Curphy, Leadership, 45.

Please cite as

Colin May, “What’s the Plan? Using Development Plans As Recruitment and Retention Tools,” Police Chief Online, January 25, 2023.